Home » Commentary » Opinion » Why Greece is the word in Queensland

A three year old government is thrown out for imposing too much fiscal austerity and being too keen to sell public assets. Greece on January 25th? Yes, but Queensland too a week later.

A three year old government is thrown out for imposing too much fiscal austerity and being too keen to sell public assets. Greece on January 25th? Yes, but Queensland too a week later.

The analogy can easily be stretched too far. Queensland, after all, has not been bailed out by anyone, nor is it at risk of leaving its currency zone. But Queensland did turn Greek in the sense that it experienced a massive deterioration in its budget and balance sheet some years ago, leading in 2012 to the election of a government focused on repairing the damage, and then to the electorate’s rejection of that government’s efforts at the first opportunity. If this is to become the pattern, it raises serious concerns.

Queensland voters seem to have forgotten just how weak their state finances had become by 2012. The rot started in 2006, as it did in all the states, but the deterioration over the next six years was larger in Queensland than in any other state. The trend was so alarming that Queensland was the first of four states to lose the coveted triple-A credit rating. By 2012 it had by far the highest debt burden (per capita or as a percentage of revenue) of the six states.

It was not just a humiliating fall for the state that had long boasted a bullet-proof balance sheet and the lowest taxes, but also a debilitating one in its implications for the government’s financial capacity to deliver quality services and satisfy infrastructure needs well into the future.

The Newman government’s fiscal repair job was not perfect. Nor was the election simply a referendum on its financial management. But the strength of the government’s efforts should be recognized, if not rewarded at the ballot box. The budget is (or was) on a path to balance in 2015-16 after eight years of out-sized deficits. Operating expenditure, having galloped ahead at 9% a year for a decade of Beattie and Bligh Labor governments, was stopped in its tracks. The debt burden had peaked and was starting to edge down. Asset sales were the obvious next stage.

The government also deserved points for leveling with the public in a mostly candid and spin-free way about the scale and nature of the problem (which is always easier, of course, when you can still blame your predecessors). Its Strong Choices survey was an unprecedented attempt by a government to communicate and consult with the public about the nature of the problem and the policy options to deal with it.

Queensland politics has long been something of a freak show and we should be careful about extrapolating the outcome of this election to other jurisdictions. It is not the first time, however, that a government has been turfed out after doing a creditable fiscal repair job. The Kennett government lost many seats after one term, and then its majority after another term, despite having made a sterling job of righting the fiscal wrongs of its Labor predecessors. Kennett’s repair job set Victoria up for more than a decade of economic out-performance of other states, but it wasn’t the Liberals that got to preside over it. The earlier Greiner episode in New South Wales bore some similarities – a hard-nosed, flinty dry government that achieved much on the economic and fiscal front but to which the electorate did not warm.

The key lesson from these experiences is not that fiscal repair, where it is needed, should or can be avoided by governments for fear of electoral retribution. Voters will punish governments that make a mess of the public finances, but will not reward governments just for cleaning up the mess. Fiscal sustainability (or whatever the punters call it) is demanded, but taken as a given. There has to be something else. Across the Tasman, the government of prime minister John Key seems to have mastered the art of doing the ‘something else’ while at the same time strengthening the fiscal position. Arguably the Hawke/Keating government did so here in the 1980s.

There are doubtless other lessons. One is that voters can be wonderfully inconsistent, at the same time intolerant of fiscal recklessness but unwilling to accept the specific measures and strategies needed to clean up the mess. The Newman government’s cuts to public service numbers aroused widespread resentment from the start, but it is difficult to see how a state budget deficit can be reduced without such cuts given the dominance of payroll costs in state outlays. The parallel in the federal budget is that social security, health and education cannot be quarantined from savings when they account for 60% of outlays. Governments have to live with these voter inconsistencies and be politically deft enough to work around them.

For the Abbott government, the lesson is that budget repair does not have to be the road to electoral ruin, but it does need to be wrapped in a larger, coherent program with a positive vision for the country.

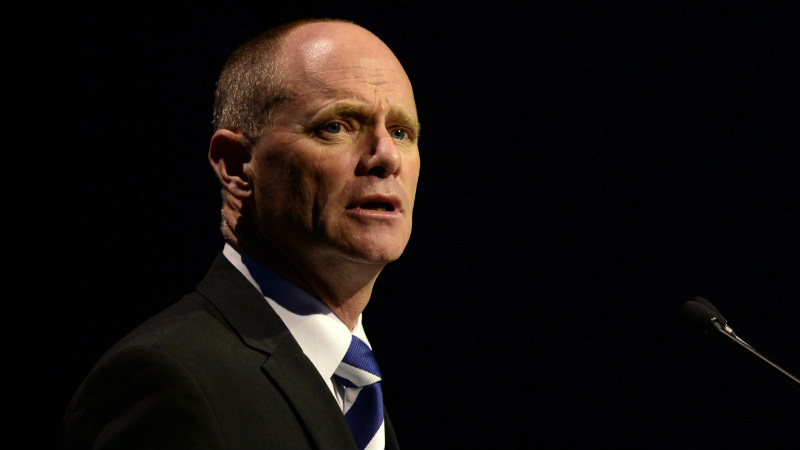

Robert Carling is a Senior Fellow at the Centre for Independent Studies

Why Greece is the word in Queensland