Home » Commentary » Opinion » Robots coming for our jobs? The data says no to Chicken Little

· CANBERRA TIMES

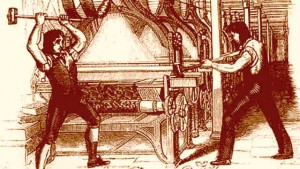

Overnight on November 10, striking workers broke into a factory and smashed up the machines, reportedly angry that the factory owners were hoarding profits and thinking of cutting jobs.

Overnight on November 10, striking workers broke into a factory and smashed up the machines, reportedly angry that the factory owners were hoarding profits and thinking of cutting jobs.

If you missed this story it’s because it happened on 10 November 1811, not 2017. But if it sounds familiar, it’s because fears over technology have been around for as long as technology itself. Indeed the term for someone afraid of technology — Luddite — comes from that 1811 revolt.

Perhaps this is why dire predictions that technology will destroy all our jobs are so persuasive: they tap into long-held fears. And those fears tend to multiply when the predictions extend to the loss of white collar jobs, in addition to typically grim prognosis for blue collar ones.

Yet is there is little or no evidence to back up concerns that substantial numbers of people are out of work from technology in the current labour market. The unemployment rate today is comparable to the rate in 1978, though it has fluctuated by several percentage points in the interim.

Moreover, the number of discouraged workers who have left the workforce as a result of being considered too old or reporting no jobs in their field or area represent less than 1% of the workforce.

There has been a rise in part-time work, which could provide support for the theory there is a growing core of workers who can’t find full-time jobs because of technological change. However, even there the evidence doesn’t support this theory: the percentage of part-time workers who want, but can’t find, full-time work actually declined from nearly 65% to just over 50% between 1996 and 2006.

It is far more likely that the rise of part-time work has other causes: especially an increase in female workforce participation.

There is little doubt some industries are shedding large numbers of workers — manufacturing in particular — but the evidence suggests that most of those workers transition to new jobs. Redundancy data suggests nearly 70% of people find work within 12 months after being made redundant, and less than 8% of workers are still out of work after 30 months.

It is important not to downplay the difficulties workers may face when experiencing long periods of unemployment. And it’s worth asking whether a government support payment aimed at assisting people during short term transitions between jobs is the best approach to helping those workers.

However, this does not represent a crisis that should cause a jettisoning of free market principles — the ones that led to Australia’s quarter century of uninterrupted economic growth — or a total redesign of Australia welfare system, as some populists like to claim.

Of course, the fact there is no problem now doesn’t mean that technology won’t be a cause for concern in the future. Yet even there, the predictions are almost comically divergent.

Frey and Osborne made major headlines in 2013 by arguing that nearly half of all jobs will be lost to machine learning and robotics. Yet a critique of that paper in 2016 found “automation and digitalisation are unlikely to destroy large numbers of jobs.”

The authors of the critique argued that workers would adapt, with less focus on repetitive routines and more on non-routine tasks. Moreover, technology would create new jobs and opportunities. And there the evidence is far better: David Gruen argues we can already see the transition towards non-routine tasks for both manual and cognitive workers.

It is a pernicious myth that all manual labour jobs are repetitive and routine, and so easily replaceable by machines.

Some tech entrepreneurs, who are likely to be simultaneously biased and knowledgeable in the area, argue that this time is different and we need to consider radical solutions like a universal basic income.

Yet the refrain that ‘this time is different’ is perhaps the most overused cliché in human history. It’s the siren call of someone seeking to argue against the evidence and dismiss the lessons of history. We have centuries of evidence of the benefits of technological change; even rapid change like the Luddites and the industrial revolution.

There is no evidence technology will create a growing cadre of unemployable former workers. Just a fear of the unknown.

So will robots take all our jobs? Maybe, but they haven’t yet and those people confidently saying they will are really just WAGs: wild ass guessers.

Simon Cowan is Research Manager at the Centre for Independent Studies and author of the report ‘UBI – Universal Basic Income is an Unbelievably Bad Idea’.

Robots coming for our jobs? The data says no to Chicken Little