Home » Commentary » Opinion » Aboriginal Australians have heard the Voice before

· DAILY TELEGRAPH

A national body can’t speak for Aboriginal people as a group and Aboriginal people won’t recognise it. Any representative ‘voice’ group that isn’t tied to country will have no authority

I was talking to an Aboriginal man at the Garma Festival last weekend, an elder from a community in another state. He said: “What I’ve heard about the Voice to parliament is nothing I haven’t heard before.” Einstein is credited with saying: “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results.”

Constitutional recognition of Aboriginal people was first proposed by then Prime Minister John Howard in 2007, passing like a baton through five more PMs before landing with Prime Minister Anthony Albanese.

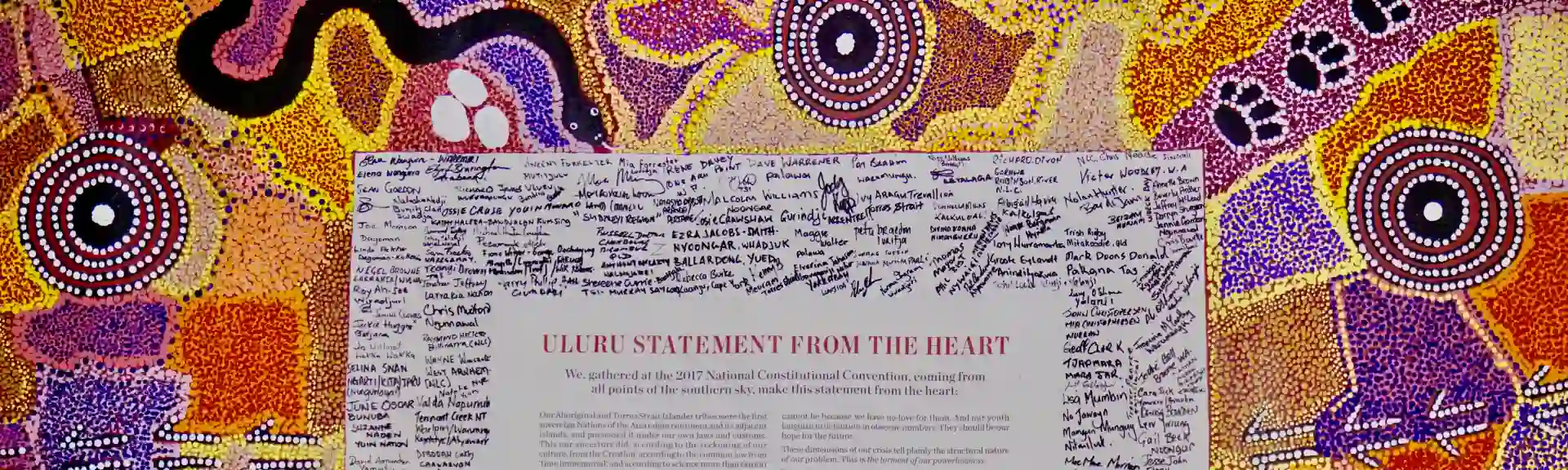

Initially about symbolic recognition, since the 2017 Uluru “Statement from the Heart” the campaign has been to enshrine a First Nations “Voice” in the constitution. The campaign is championed by Australia’s elites, including corporate Australia, media figures and Aboriginal academics.

When I speak to Aboriginal people day-to-day I don’t find support, but rather indifference, confusion as to what it’s about or outright opposition. I know why. The Voice, like the representative bodies before it, is not built around Aboriginal cultures and how we look at ourselves.

This week we are told that the proposal will be to add three provisions to the constitution:

1. There shall be a body to be called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.

2. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice may make representations to parliament and the executive government on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

3. The Parliament shall, subject to this constitution, have powers to make laws with respect to the composition, functions, powers and procedures of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.

My first reaction was why amend the constitution at all? The Commonwealth government already has power to create Aboriginal representative bodies and has before including the National Aboriginal Consultative Committee, ATSIC and the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples.

It could legislate tomorrow to create a Voice. No referendum. The previous bodies all made representations to parliament, as do many other Aboriginal bodies and individuals all the time. Recent changes to the Closing the Gap targets were made on advice from Aboriginal community bodies known as the Coalition of the Peaks.

When down in parliament, I’m always tripping over blackfellas there to talk to politicians and public servants. Aboriginal people don’t need constitutional permission to tell government what they think.

The most important thing about the Voice — its composition, functions, powers and procedures — won’t be in the constitution at all but decided by parliament.

The government of the day can make the Voice anything it wants: from a small, hand-picked committee to hundreds of elected members or anything in between. Enshrining the Voice in the constitution doesn’t depoliticise it; quite the opposite.

But the main reason I remain unsupportive is if Aboriginal Australians are to have representative bodies to speak on things that matter to us, those bodies will fail if they conflict with our own identities. There isn’t one Aboriginal group but hundreds, each with their own country, language, kinship system and culture.

A year after the Uluru Statement of the Heart I was in Mutijulu, a small community at the base of Uluru, and a local elder took me aside to tell me that the Uluru Statement of the Heart was not their culture and does not speak for them. What they were talking about is that traditional owners of a particular country are the only people who can speak for that country.

A national body can’t speak for Aboriginal people as a group and Aboriginal people won’t recognise it. Likewise a regional body that spans and has membership of different countries.

Any representative group that isn’t tied to country will have no authority to be anyone’s voice. I predict the Voice will be just another bureaucratic structure that further entrenches government in Aboriginal lives.

Despite the missions and reserves being disbanded since the late 1960s, Aboriginal people are the most over-governed people in Australia. We need less government, not more.

Nyunggai Warren Mundine AO is the Director of the Indigenous Forum, Centre for Independent Studies

Aboriginal Australians have heard the Voice before