Home » Commentary » Opinion » Net Zero By 2050? Don’t Plan on It

· Wall Street Journal

As leaders prepare to gather in Glasgow for the United Nations climate-change conference, you may think the world has agreed to reduce and eventually eliminate its dependency on fossil fuels, stepping up its reliance on renewable energy. Even Australia’s Prime Minister Scott Morrison, who won an election opposing costly climate policies, now proudly embraces net-zero emissions by 2050.

As leaders prepare to gather in Glasgow for the United Nations climate-change conference, you may think the world has agreed to reduce and eventually eliminate its dependency on fossil fuels, stepping up its reliance on renewable energy. Even Australia’s Prime Minister Scott Morrison, who won an election opposing costly climate policies, now proudly embraces net-zero emissions by 2050.

But the timeline for the transformation is entirely unrealistic. The politicians who make promises about how energy will be delivered within three decades can be fairly certain that they will be merely footnotes in history. British Prime Minister Boris Johnson claims that all cars sold in Britain will be electric by 2030. But he doesn’t acknowledge that on current trend there won’t be enough electricity to power all of these cars.

Climate enthusiasts admit that achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 presents some difficulties. But they quickly shift to talking up the exciting technological challenge, because, according to Australia’s iron-ore billionaire Andrew Forrest, “there are tens of billions of dollars around the world looking to invest in renewables” and eventually in industries such as hydrogen. Activists also suggest that dissent is an affront to international opinion.

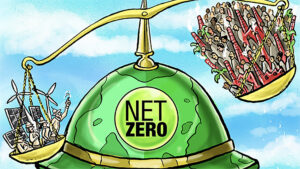

Yet as the West strives to cut emissions, the developing world doesn’t, particularly India and China, the two most populated countries on the planet. Global energy consumption is expected to increase 50% by 2050, a rise fueled mostly by developing countries that want energy not to spite the planet or to offend international opinion, but to raise living standards as best they can.

For decades the developed world has implored these countries to trade with the West and not simply rely on handouts from richer countries. In many cases, these rising countries can trade thanks to manufacturing processes and energy sources no longer considered acceptable in polite Western society, namely coal.

The West would do well to remember that it became prosperous through industrialization, a process that relied heavily on fossil fuels. When Britain led the industrial revolution in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, it did so entirely on the basis of coal, which powered its factories and later its railways.

Other countries did the same. Now the West uses its supposed moral and economic superiority to lecture other countries on the need to curb their behavior, even if it means retarding their own economic progress and making themselves more dependent on richer countries. This is a form of colonialism, which makes the left’s attraction to it all the more bizarre.

Renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar power, aren’t up to the job of powering the world’s economies. There isn’t enough wind in much of the world to get the turbines turning. Fossil fuels may well be damaging to the health of the planet, but the retreat around the world from nuclear power was shortsighted, especially in countries that lack viable alternatives.

Europe is weathering an energy crisis because of the caprice and spite of Vladimir Putin, who is manipulating the price of the gas Russia provides to Germany and other parts of Europe. This has pushed prices up to a point where not only domestic customers but industrial ones find energy costs reaching prohibitive levels. In Britain, ceramics manufacturers have told a hapless government that they may have to shut down because they can’t afford Mr. Putin’s prices.

In Australia, Mr. Morrison feels compelled to announce net zero so he doesn’t let down Canberra’s Aukus partners, the U.K. and the U.S., which enthusiastically support unilateral decarbonization. Yet by weakening the economies of the West, net zero is a boost to a rising China.

Instead of rhetoric designed to make environmentalists feel smug, Western governments need proper contingency plans for their own energy supplies. Politicians should avoid relying too heavily on renewables, even if that means using coal to power generators or a renaissance of nuclear power to keep the world’s lights on. And the developing world deserves the same chance the developed one had.

One day, with technological breakthroughs, it will be possible to power the world without fossil fuels. But that day isn’t coming soon, and it’s foolish to pretend otherwise.

Net Zero By 2050? Don’t Plan on It