Home » Commentary » Opinion » Why the New Testament shouldn’t come with trigger warnings

· The Spectator

Demands for the New Testament and Koran to contain alerts in the margins of those passages that have been used to justify and promote anti-Semitism should come as no surprise in our increasingly trigger-obsessed times.

Demands for the New Testament and Koran to contain alerts in the margins of those passages that have been used to justify and promote anti-Semitism should come as no surprise in our increasingly trigger-obsessed times.

The European Jewish Congress (EJC), an umbrella organisation for Jewish groups in Europe, recently produced a catalogue of policies to combat anti-Semitic hatred. EJC president Moshe Kantor called for scriptures to include “marginal glosses and introductions that emphasises continuity with Jewish heritage [and] warn readers about anti-Semitic passages in them.”

You might think this is just the latest instance of our contemporary obsession with tearing down the past and correcting anything sculpted, painted, or written more than five minutes ago. What next? Trigger warnings beside the Rosetta Stone, or alerts for vegans queueing to admire the hunting artwork of the Lascaux Caves? But wait… It is worth examining why such a move on the part of the EJC is understandable.

Anxiety about anti-Semitism is well founded. It is now rising to new levels in Europe – just 70 years after the Holocaust. This has prompted many Jews living on the continent to ever higher levels of vigilance as they pay close attention to the language and actions of their political leaders.

Young Austrian Chancellor, Sebastian Kurz, is emphatic that a Europe without Jews is no Europe at all. But, British Labour’s ageing leader, Jeremy Corbyn, offers little assurance to Jews, and spices his equivocation about the anti-Semitism endemic in the UK Labour Party by roundly and regularly denouncing Israel whilst honouring his ‘friends’ in Hamas.

And don’t forget that across the Atlantic, in a most violent and shocking act of hatred, Jewish worshippers were recently gunned down at a Pittsburgh synagogue. Little wonder that Jewish organisations are looking for new ways to anticipate and counter acts of Jew-hatred. The devil of anti-Semitism continues to stalk the earth.

Anti-Semitism is humanity’s greatest and most persistent hatred; and disturbingly, it has fed for centuries on the teachings of other religions. Islam holds all Jews (and Christians) to be subservient – a status to be acknowledged in their legal designation as dhimmis. Dhimmitude continues to heap humiliation on the heads of Jews.

But the devil of anti-Semitism has also supped on Christian teachings about Judaism — Martin Luther, for instance, was a notorious anti-Semite — as well as on passages in the New Testament that blame the Jews for the crucifixion of Jesus. Hence, the greatest source of Christian anti-Semitism is the claim that every Jew in every age is a ‘Christ-killer’.

Whereas Jesus of Nazareth, a pious Jew, was sure he knew what God wanted from the people of Israel, the Jewish leaders of the day were equally sure that they knew, too. And the consequences of that early religious split continue to roll through the ages of history. This was something acknowledged in 2016 by Justin Welby, Archbishop of Canterbury, who declared that the church had been complicit in spreading the virus of anti-Semitism.

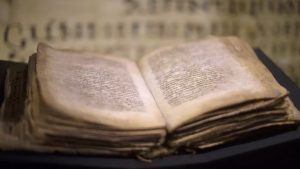

Given that grim history, a decision to publish trigger warnings about passages in scriptures that have been used to encourage anti-Semitism might seem like a sensible idea. After all, trigger warnings are intended to signal that potentially distressing materials are about to be encountered. However, the trouble is that as you leaf through the Bible, material with the potential to disturb leaps out at you from almost every page, threatening to trigger feelings or memories.

It might be a vision of slaying the children of one’s enemies (Psalm 137); or calling down divine fire to incinerate the disobedient (2 Kings 1); or an adulterous king who has his lover’s husband conveniently slain in battle (2 Samuel 11); or a brutal execution (Acts 7). In the Bible, you’ll also find a hair-raising account of preparations for an act of child sacrifice forestalled by the last-minute intervention of the angel of the Lord (Genesis 22); and the bloody beheading of a man at the behest of a vindictive woman (Matthew 14).

No doubt about it: the Hebrew and Christian scriptures — or Old Testament and New, as they are known to many — embrace the broadest range of human life and experience and contain abundant moments of bloody vengeance, vindictive vituperation, and downright nastiness that can to alarm the sensitive or tantalise the hate-filled. (It is, for example, often overlooked that Anders Behring Breivik claimed it was Christianity that motivated his killings in Norway in 2011.)

And some of the content in the New Testament — especially in St John’s Gospel -—– is overtly very derogatory about the Jews, and especially about the Jewish leaders with whom Jesus was in constant conflict; resulting in his death. This prejudice finds its way into the great music of J.S. Bach, whose St John’s Passion remains, to this day, deeply distasteful to many.

So, there’s much to be disturbed by in the Bible, and plenty there that can cause offence and distress. But this kind of New Testament material demands to be confronted and engaged with; it needs to be interpreted, criticised, and explained for what it is: ancient writings whose Christian authors were motivated by the belief that the arrival of the new, in the figure of Jesus Christ, called for the dismantling of the old, in the form of the Jewish legal and religious establishment.

But to insert trigger warnings in the margins of these texts is to side-step these thorny questions of interpretation rather than to confront them head-on. For the problem with trigger warnings of any kind — and the reason they threaten such mischief — is that instead of maintaining the focus of study on the text itself and upon the intent of the writer, they shift it towards a self-absorbed and self-indulgent focus on the impact of the text on the reader.

Indeed, this shift away from intent to impact lies at the heart of the bitter culture wars currently being waged on some of our university campuses. Far from minimising discomfort, trigger warnings inserted beside testing passages of scripture could actually inflame sensitivities and cause people to withdraw from confronting anti-Semitism at just the time when they need to do battle.

Peter Kurti is a Senior Research Fellow at The Centre for Independent Studies.

Why the New Testament shouldn’t come with trigger warnings