Introduction

Royalty payments by mining companies for extracting resources, including large volumes of fossil fuels, are major revenue streams for state governments. Those royalties help fund essential services such as health and education, supporting the employment of teachers, nurses, and public servants. Yet there is a growing hostility to mining in some parts of the community due to concerns over environmental degradation and climate change, and there is a risk that policymakers could throttle an industry that contributes substantially to our economy and government budgets.

This paper argues that mining royalties are a significant benefit to Australia, providing essential funding for state and territory governments to invest in crucial infrastructure and public services. Further, they constitute essential own-source revenue for states and territories. Without them, those governments and their constituents would be even more dependent on the Commonwealth for funding, worsening the ‘blame game’ and inefficiencies that arise from Australia’s vertical fiscal imbalance — the mismatch between the states and territories’ heavy spending responsibilities and their lesser revenue-raising capacity compared with the Commonwealth.

This paper reviews how Australians are compensated via royalties for the mineral resources extracted. It considers the value of those royalties and the alternatives for state governments. It also considers the pros and cons of different ways of maximising the value of our resources, comparing royalties with resource rent taxes and state-owned resources companies, as seen in Norway. Finally, it concludes with implications for public policy. NB: For the purposes of the paper, the term ‘states’ is taken to include territories.

To listen to this research on the go, subscribe on your favourite platform: Apple, Spotify, Amazon, iHeartRadio or PlayerFM.

Australia’s coal, oil and gas, and mineral resources

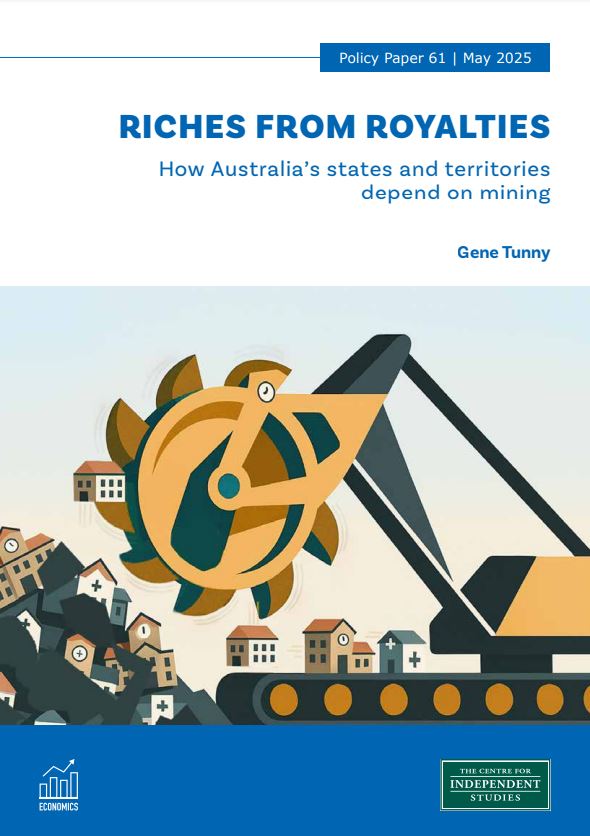

The Australian continent has vast fossil fuel and mineral resources, with over $2 trillion in demonstrated resources (Figure 1). Approximately 44% of the total value is from iron ore, while 37% comes from fossil fuels: coal, gas and other petroleum resources.

Figure 1. Australia’s value of Demonstrated Mineral and Energy Resources by Commodity as of 30 June 2024, $ billion

Source: ABS, 5204.0 Australian System of National Accounts, Table 62.

Australians via the Commonwealth (offshore) and states (onshore) own the resources underground, which is different from the the situation in the United States and some other countries. This allocation of ownership affects the abilities of different levels of government to earn income from the resources and the means they can choose from, as discussed in the next section.

What royalty revenues have governments been earning?

Given their ownership of the relevant resources within their borders, Australia’s states are entitled to levy royalties for coal, oil and gas, and minerals in the ground. Additionally, the Northern Territory has the right to levy royalties under the Northern Territory (Self-Government) Act 1978. As discussed above, the Commonwealth owns offshore resources, such as those in the North West Shelf off WA, and this has been the case since the Sea and Submerged Lands Act 1973. However, the Offshore Petroleum (Royalty) Act 2006 provides specific provisions for assessing and collecting royalties from offshore areas, including the North West Shelf. The Western Australian Department of Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety (DMIRS) administers these royalties on behalf of the Commonwealth, but the revenue is shared according to an agreed-upon formula. In contrast to royalties, the Commonwealth’s means of being compensated for non-renewable resources being extracted is the Petroleum Resource Rent Tax (PRRT), which, as discussed below, has significant shortcomings.

Royalty revenues fluctuate with commodity prices and export volumes. In 2022-23, Queensland earned a record $15.4 billion in coal royalties due to very high coal prices. This was after the previous state government increased royalty rates in mid-2022, risking future investment in the sector, as discussed below. Across the states, coal, oil and gas royalties will exceed $38 billion over the next four years (2024-25 to 2027-28) — over $9.5 billion yearly (Table 1). Fossil fuels account for just over half of the total forecast royalty revenues, with the major mineral contributor to royalties being Western Australian iron ore, expected to earn nearly $24 billion for WA over four years and comprising the bulk of its expected $30 billion of royalty revenues. From 2024-25 to 2027-28, average royalty revenue for the states and territories will equal $18.4 billion yearly. This amounts to approximately 4.3% of general government revenues across all states and territories.

Table 1. State and territory government revenues from royalties, budget estimates

Source: State and Territory budget papers.

This income forms a significant part of state budgets and goes into consolidated revenue to fund public services. Through horizontal fiscal equalisation overseen by the Grants Commission, this revenue ends up benefiting all states — although effectively WA gets to keep much more of its iron ore royalty revenue than justifiable under HFE, owing to a highly favourable deal regarding its GST share, which sees the Commonwealth topping up grants to WA.[1] Hence, all states benefit from royalties, and WA especially so under current arrangements. QRC Chief Executive Ian Macfarlane recognised the redistribution of state royalty revenue in his commentary on the 2022 coal royalty rate hike in Queensland: “What the government also isn’t telling people is that because of the GST equalisation process, 80% of the extra royalties raised will be redirected to Canberra over the next five years anyway.”[2]

Furthermore, given the significance of federal grants in state budgets, state governments also benefit partly from the federal offshore PRRT revenue, amounting to a projected $6.9 billion over the next four financial years (2025-26 to 2028-29), averaging around $1.7 billion each year.[3] Additionally, the Commonwealth receives smaller amounts of royalty revenue, from the royalties on North West Shelf oil and gas that it shares with WA ($367 million in net terms), and from crude oil and condensate excise ($597 million in 2022-23).[4]

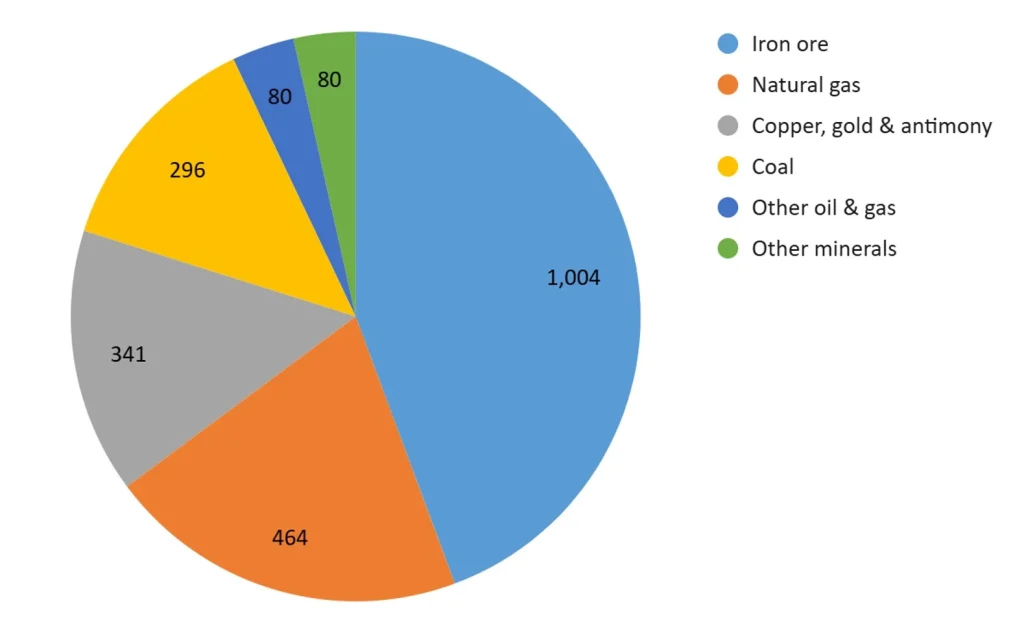

The value of royalties to state budgets changes significantly over time. It peaked in 2022-23 — affected by the high fossil fuel prices mainly associated with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — and has fallen since then (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Royalties revenue of state and territory governments

Source: ABS Government Finance Statistics and state and territory budget papers.

Regardless, royalties are much higher in real terms than before the first phase of the 2000s mining boom, commencing around 2003-04. Consider the National Accounts item labelled ‘Rent on natural assets’ for the general government sector, the vast majority of which is for mining royalties, with a minor contribution from land rents. The contribution of rent on natural assets has surged from around 1½% of total income for the state and local general government sector before 2003-04 to 7½% in 2023-24 (Figure 3). For the general government sector, including the Commonwealth, rent on natural assets has increased from around 1% to 3¼% of total income. The contribution of rents on natural assets to Commonwealth income has remained tiny, at fractions of a percentage point, reflecting both the limited ownership of natural resources (i.e. only offshore) and arguably the poor design of the PRRT, discussed below.

Figure 3. Rent on natural assets as a percentage of gross income, general government, Australia, 1972-73 to 2023-24

Source: ABS System of National Accounts.

What would governments do without mining royalties?

As established above, state budgets are highly vulnerable to any shift away from fossil fuels. To understand the significance of mining royalties, consider that the average annual $9.5 billion of royalties from fossil fuels could fund the construction of seven or eight new city hospitals, 25 to 30 new regional hospitals or 60 to 70 new schools. This estimate is based on recent costs of constructing hospitals and schools, such as the $1.3 billion Toowoomba Hospital, $320 million Mount Barker Hospital, and the $154 million Brisbane South State Secondary College.

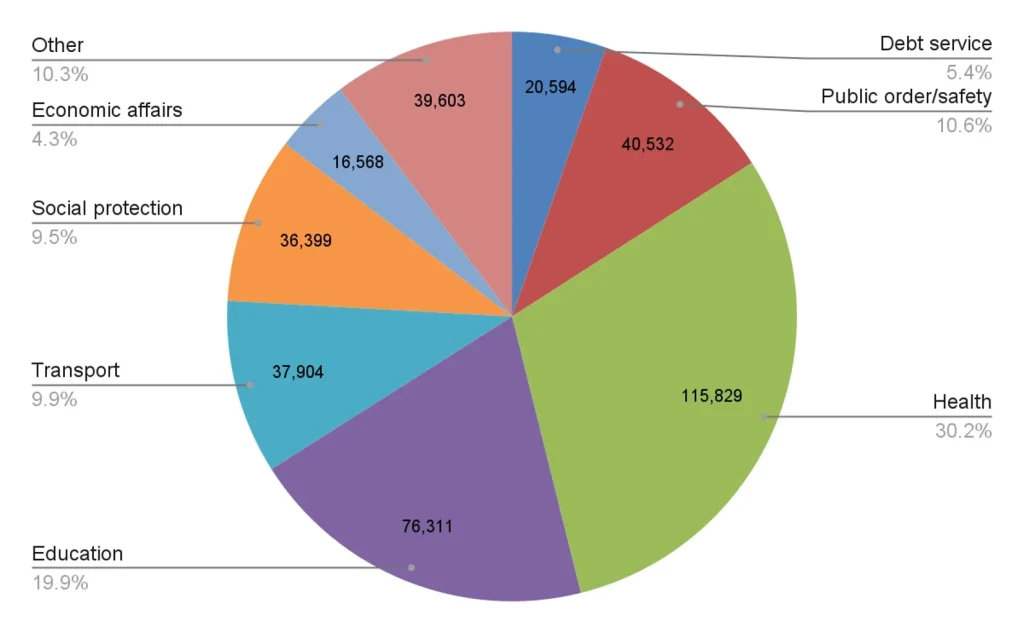

Of course, money is fungible, and it is impossible to say mining royalties funded any particular hospital or school. Instead, they go into consolidated revenue and support various government activities. Health and education account for around half of state government expenses, followed by public order and safety (i.e. police and the courts), transport, and social protection, among other functions (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Total State General Government Expenses by Purpose ($ million), 2023-24

Source: ABS, Government Finance Statistics, Australia, 2023-24

There are around 1.25 million full-time equivalent (FTE) state general government employees across Australia in 2024-25.[5] According to budget estimates, royalties will provide around 5% of state general government revenue in 2024-25. Hence, we can say that royalties fund the employment of an estimated 62,500 FTE public servants, including policy advisers, teachers, nurses, police officers, and many others. The royalties from fossil fuels (at around 2.7% of general government revenues) supported over half of these public servants, around 34,000 FTEs. To further illustrate the importance of royalties, consider data for a specific occupation: teachers. There were around 199,600 FTE teachers in government schools in Australia in 2024.[6] Around 10,000 of these teachers are supported by mining royalties, with around 5,400 supported by fossil fuel royalties.

If coal and gas royalty revenue were unavailable, state governments would need to raise more money elsewhere, such as through higher motor vehicle registration or payroll taxes. The eastern states currently have high and increasing levels of debt and no scope to absorb significant revenue reductions.

To compensate for a loss of royalties, there is a risk that state governments would increase taxes or charges damaging to work and investment incentives and economic activity, such as payroll tax or transfer duties. For example, Victoria University’s Centre of Policy Studies (CoPS) found that property transfer duties and insurance duties “caused losses in economic activity of 80 cents and 40 cents per dollar of revenue raised respectively”.[7] This is especially concerning when it is considered that royalties, paid by mining companies that are primarily foreign-owned, have a much lower welfare loss or even a welfare gain, as discussed below. Australia’s economy would suffer if revenue-equivalent amounts of stamp duties replaced royalties.

Is there a better way to benefit from our resources?

This is not to say that our royalty and taxation settings for coal, oil, gas and minerals are perfect.[8] Indeed, they have been highly contested. Recall the debate over the Resources Super Profits Tax during the time of the Rudd government.

Generally, royalties are not considered taxes and are separately identified in budget reporting. One view of royalty payments is that they are payments made to purchase resources from the community by mining companies. The issue is how to design them to encourage the extraction of resources so the community gets the best return on them. Many economists consider royalties an inefficient way to do this because they can discourage the extraction of resources in times of lower prices.

Governments are aware of this problem and generally have ad valorem and progressive royalty rates. However, that does not entirely remove the problem. Progressivity can mean high rates over a range of prices, rates so high they deter new capital investment. Queensland discovered this when it hiked its coal royalty rates in 2022, raising questions about Queensland’s policy stability as an investment destination. It appears it has deterred some new investment in coal mines, too (Box 1).

Box 1. Queensland’s coal royalty hikeIn 2022, the Queensland Government implemented a significant increase in coal royalty rates, marking a notable shift in its approach to resource taxation. High mining royalties can diminish the profitability of mining operations, leading to reduced investment, job cuts, and even mine closures, which in turn may destabilise the broader regional economy. Previously, the first $100 per tonne was taxed at 7%, any amount between $100 and $150/tonne was taxed at a higher rate of 12.5%, and any remainder above $150/tonne was taxed at 15%. The new rates introduced a more progressive structure, applying the same method as before, with three new tiers: 20% for prices between $175 and $225 per tonne, 30% for prices between $225 and $300 per tonne, and 40% for prices above $300.[9] The Queensland government justified the increases as a necessary adjustment to secure additional revenue for public services and infrastructure projects amidst rising commodity prices and increasing global demand for coal. The effective royalty rates of premium metallurgical coal in Queensland jumped from 14% (before the introduction of the new rates) to 23% in September 2022.[10] They are set at the highest rate in the world, followed by India with 14% ad-valorem on the price of coal (excluding the state of West Bengal), and Indonesia with different rates based on calorific value and the government’s benchmark coal price, with 13.5% as the maximum rate. The Japanese ambassador to Australia and Mike Henry, the CEO of BHP, voiced strong concerns about the Queensland Government’s 2022 coal royalty increase.[11] The Japanese ambassador highlighted the potential negative impact on trade relations, emphasising that Japan, a major importer of Queensland coal, might seek alternative suppliers. He cautioned that the new rates could undermine the longstanding economic partnership between Japan and Queensland. Similarly, Mike Henry criticised the royalty hike, arguing that it would hurt the competitiveness of Queensland’s coal industry on the global stage. He warned that the additional financial burden could lead to reduced investments and jeopardise future projects, ultimately affecting jobs and economic growth in the region. Glencore decided to cancel its $2 billion Valeria coal project in Queensland, citing the state’s 2022 increase in coal royalty rates as a significant factor.[12] The new royalty structure, which introduced the highest coal royalty rates in the world, raised investor concerns and damaged confidence. Glencore highlighted that abrupt policy changes, like the Queensland Government’s royalty hike, increased uncertainty and raised red flags with key trading partners. |

Even setting aside the extreme case of Queensland’s 2022 royalty hike, there is a widespread view among economists that royalties are a terrible way for Australia to receive compensation for the extraction of its non-renewable resources. Given the purported inefficiency of royalties, Treasury’s 2010 report from the Australia’s Future Tax System review instead advocated a tax on the economic rent associated with resource extraction. Economic rent is a super-profit, profit above what was required to compensate investors for the cost of capital and to encourage investment in the first place.

Theoretically, a tax on pure economic rents would be perfectly efficient and not discourage resource extraction. However, as discussed in this section, a preference for resource rent taxes over royalties is questionable in Australia for the following reasons.

- Royalties are likely not as economically damaging as KPMG Econtech’s estimates suggest.

- Resource rent taxes have had a poor record of implementation in Australia, and there is little reason to expect they will be implemented better in the future.

- Switching from state and territory royalties to a Commonwealth resource rent tax would be detrimental to efficient fiscal federalism and further narrow the scope of state and territory revenue autonomy.

These points are now considered in turn.

Economic efficiency

In a widely cited study for the above 2008-10 tax review, KPMG Econtech estimated the marginal excess burden (MEB) for mining royalties at 70 cents in the dollar and the average excess burden (AEB) at 50 cents.[13] The excess burden of taxation (also called deadweight loss) is the reduction in economic welfare that arises because taxes distort individuals’ and firms’ behaviour, causing them to change their production, consumption, or investment decisions. The average excess burden is the total deadweight loss divided by the total amount of tax revenue, indicating how costly each dollar of revenue is in terms of lost efficiency. The marginal excess burden, on the other hand, measures the additional deadweight loss incurred by raising one more dollar of tax revenue, capturing how each incremental increase in revenue adds to the overall distortion. The high rates of MEB and AEB for royalties compare with an MEB of 8 cents and AEB of 6 cents for the Goods and Services Tax (GST) and 24 and 16 cents, respectively, for labour income taxation.

However, KPMG Econtech’s excess burden estimates were challenged by Henry Ergas and Jonathan Pincus.[14] Given the high level of foreign ownership, the burden of royalties falls mainly outside Australia, so the excess burden is far lower. That is, it is foreign investors who are disproportionately disadvantaged by the reduction in mining output and profits related to royalties. In any cost-benefit analysis or economic welfare analysis, it is the wellbeing of a country’s residents that matters, not that of foreigners. Ergas and Pincus estimated foreign ownership was “over eight-tenths of the equity in Australian mining companies”, while the Australia Institute has reported 86% foreign ownership, based on Australian Treasury data on contributions to capital costs of major projects.[15] KPMG Econtech’s estimates do not consider foreign ownership when calculating the excess burden of royalties. If the transfer of welfare from foreign owners to Australian taxpayers is correctly accounted for, Ergas and Pincus note, “the incidence of royalties on foreign owners of Australian mining equity provided excess benefits to Australia of 83 cents (black coal) and 89 cents (iron ore) per dollar of public revenue…more than sufficient to offset the 50 cents excess burden found by KPMG Econtech.”[16]

To summarise, mining royalties — at reasonable rates — are not as economically damaging to the jurisdiction imposing them as often assumed by advocates of resource rent taxes.

Australia’s dubious record with resource rent taxes

Economic theory tells us resource rent taxes are an efficient way to tax non-renewable resources. That may be so, but they have proven fiendishly challenging to implement effectively in Australia; partly because it is difficult, if not impossible, to develop a formula that only provides for taxation of the ‘rent’ component of profits. Further, as profit and hence the rent will be much more volatile than revenue, resource rent tax revenue will be much more volatile than royalties revenue, complicating budget management. The Rudd-Gillard government’s resource rent tax raised much less revenue than expected. In 2012-13, the resource rent tax was initially expected to raise $3 billion, but this was later revised down to $2 billion and, even worse, around $200 million.[17]

The federal government’s oldest resource rent tax, the PRRT, has also faced challenges. Critics allege the PRRT is raising insufficient revenue, and some favour replacing it with a royalty regime.[18] Part of the problem is that the PRRT was designed to tax oil rather than gas, which requires more extensive downstream processing — i.e. refrigeration to create liquefied natural gas (LNG).[19] This means there is greater scope for transfer pricing to shift profits to downstream activities, meaning less taxable income for the PRRT.

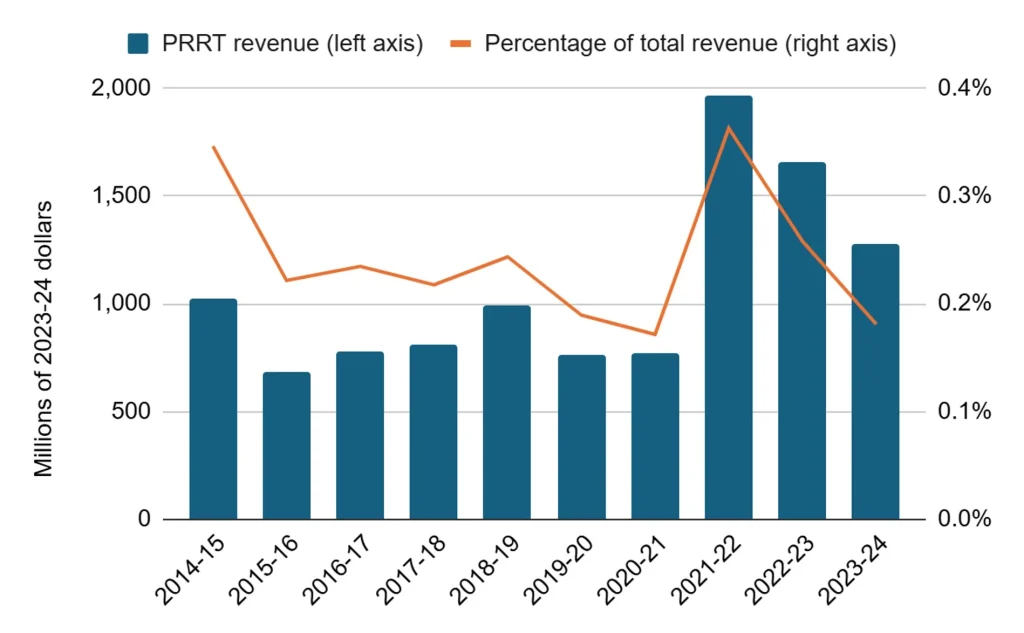

The $1-2 billion in PRRT revenues per annum are small relative to state government royalties and LNG exports that reached $92 billion in 2022-23, although, of course, the appropriate comparator is taxable income.[20] The federal government has made some adjustments to the PRRT since the review by former Treasury Deputy Secretary Mike Callaghan in 2016 and the 2023 Treasury review of gas transfer pricing arrangements. Changes have included reducing ‘uplift rates’ that compound deductions over time, allowing maximum deductions of 90% of assessable PRRT income and adjusting the transfer pricing rules. However, the PRRT is still seen as a disappointment by critics.[21] Revenue raised by the PRRT is not expected to be higher at the end of the current budget forward estimates, although it is significantly higher for a few years, peaking at $1.98 billion in 2025-26 before declining. By 2028-29, it is estimated to be $1.45 billion compared with $1.50 billion in 2024-25.[22]

Figure 5. PRRT revenue, accrual basis

Source: Australian Government Final Budget Outcome reports, 2014-15 to 2023-24 and ABS Consumer Price Index, Australia. Note: Revenue estimates were converted to 2023-24 dollars using headline CPI.

Overall, it is difficult to judge the merits of the criticism of the PRRT — and it is beyond the scope of this paper. Oil and gas companies made substantial capital expenditures in the 2010s in new developments, and significant depreciation expenses allowed them to reduce their liabilities for PRRT. It may be too soon to tell whether the PRRT is a failure. That said, the early signs have been concerning, and it remains to be seen what further changes the Government may make and whether they will significantly boost PRRT revenue.

The policy lesson relates to the challenges of implementing theoretically elegant resource rent taxes. Even if well designed, the lack of revenue in early years, as companies deduct significant depreciation expenses associated with large capital expenditures, can be disheartening and reduce the appeal of resource rent taxes for governments. For this reason, the IMF recommends that developing economy governments supplement resource rent taxes with a royalty to earn revenues from when projects begin production.[23]

Vertical fiscal imbalance

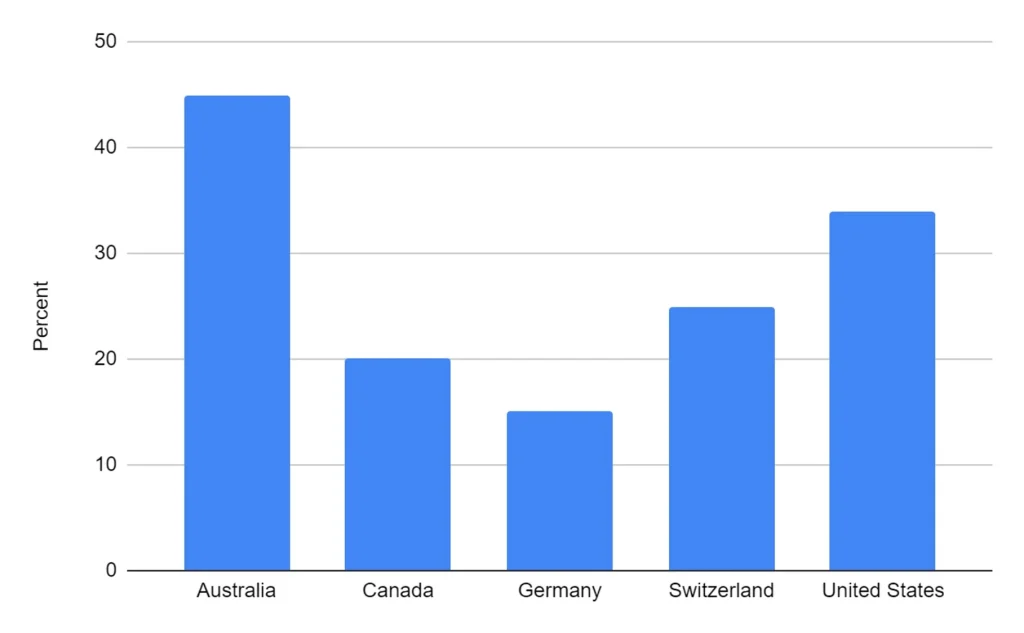

Replacing state royalties with a Commonwealth resource rent tax would increase Australia’s vertical fiscal imbalance (VFI) — the large gap between the states’ revenue-raising capabilities and expenditure responsibilities, whereby Commonwealth grants fund nearly half of the states and territories’ spending. As the Commonwealth Grants Commission has identified, the extent of Australia’s VFI is much greater than that of other advanced economy federations such as the US, Canada, and Switzerland (Figure 6). Measuring VFI by federal grants as a percentage of state and territory government revenue, Australia has two-to-three times the degree of VFI in Canada, Germany, and Switzerland. The US has a VFI of approximately 34% of state revenue, but is still significantly below our level at around 45%.

Figure 6. Degree of VFI (ie grants to sub-national governments as a percentage of total revenue), circa 2021-22

Source: Commonwealth Grants Commission (2022, Table 2, p. 21) and, for the United States, Adept Economics’ calculations based on US Census Bureau’s 2021 Annual Survey of State Government Finances Tables, available at https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2021/econ/state/historical-tables.html.

Commonwealth grants to the states go well beyond what is envisaged in the theory of fiscal federalism, where some grants may be optimal given spillovers of state government service delivery to other states. The level of assistance creates a dependency and an unhealthy dynamic between the Commonwealth and the states. Former Queensland Premier Wayne Goss once compared the relationship to “a dialogue between a begging bowl and a baseball bat”, with the Commonwealth holding the baseball bat.

The dependency of the state governments on the federal government provides them a convenient excuse for any failures in service delivery. The state governments would prefer not to increase state taxes and charges to fund public services, as they would rather the Commonwealth bear any political cost of taxation. Furthermore, VFI creates a moral hazard, as state governments rely on Australia’s generally sound international reputation as a borrower to increase their borrowings to very high levels.

Given the well-known problem with VFI in Australia, maintaining royalties as a source of revenue for state and territory governments is essential.

Australia versus Norway

Australia is often compared unfavourably to Norway, which has built up a vast US$1.8 trillion sovereign wealth fund seeded by North Sea oil and gas proceeds.[24] However, a comparison with Norway is problematic for several reasons.

First, the Norwegian approach involved developing a state-owned oil company, Equinor (formerly Statoil), which involved a lot of risk on the public balance sheet. The investment has paid off, but it was always risky. Australia has preferred to rely on mining companies to take the risks. Indeed, the variety and geographic spread of our fossil fuel and mineral resources would have made it more challenging for widespread public sector involvement.

Second, Norway is, and historically has been, a high-tax country and hence was able to divert oil and gas proceeds to a sovereign wealth fund rather than using them to support budgetary expenses (Figure 7). Indeed, it has always had higher taxation than Australia, even before North Sea oil and gas developments in the 1970s.

Figure 7. Tax to GDP, all levels of government, Norway versus Australia

Source: Revenue Statistics – OECD countries: Comparative tables.[25]

Third, Australians should not be too disappointed in the role that states have played in developing our resources. In many cases, they have enacted policies and struck deals with mining companies to promote the extraction of resources that otherwise would have stayed in the ground. For example, in the 1960s and 1970s, Queensland policymakers did deals that facilitated foreign investment and extracted significant amounts of money, probably some ‘rents’ (i.e. super-normal profits), via royalties and rail charges. David Lee, in his history The Second Rush, about Australia’s second mining rush after the Gold rush in the 19th century, explains:

“In Queensland, the State government encouraged coal industry development largely through foreign capital. It also enabled coal to be hauled on the State railway system subsidised by the new mining companies. The Queensland government would gain much of its revenue in the second minerals rush through rail charges on coal.”[26]

Policymakers may have been less savvy in recent years. For instance, significant debate exists regarding whether approvals should have been given for the LNG export facilities at Gladstone without a gas reservation policy. While it made sense economically for the resources to be sold at the higher price available in the export market, the connection of the domestic and international markets has led to a surge in gas prices that have put pressure on Australian manufacturers once reliant on cheap gas. At the same time, there have been accusations of abuse of market power by the gas companies, and additional gas supply from more liberal approaches to gasfield developments in NSW and Victoria would be insufficient to improve gas affordability.[27] This debate is beyond the scope of this paper to resolve.

Longer-term outlook: Implications of decarbonisation

In this section, I discuss how the outlook for royalties, particularly fossil fuels royalties, is highly uncertain. If fully pursued, decarbonisation will have significant implications for royalty revenue. However, it must be borne in mind that metallurgical or coking coal production and exports are more valuable than thermal coal, and coking coal will be difficult to substitute in steel production (Figure 9). Note that Queensland’s royalties will fare better than NSW’s because Queensland has the bulk of coking coal as opposed to NSW, which mainly produces and exports thermal coal.

Figure 8. Australian Government Office of the Chief Economist forecasts (Mar-25 to Dec-26) of fossil fuel exports, Australia

Source: Resources and Energy Quarterly Forecast Data, https://www.industry.gov.au/publications/resources-and-energy-quarterly-march-2025, accessed on 29 April 2025. Note: ‘f’ stands for forecast.

Strong global population and economic growth into the future will continue to deliver strong demand for resources, although outcomes will differ substantially for different commodities. The State government’s Queensland Resources Industry Development Plan (QRIDP) has identified several global trends that will reshape the resources industry in the following decades, including higher demand for resources in the Indo-Pacific region, changes in suppliers due to reputational factors, and emerging innovations in the industry.[28]

Over the next decade, coal demand may not fall substantially, given current policies across the world, while the outlook beyond the next decade depends substantially on global policies regarding GHG emissions abatement. The IEA’s Stated Policies Scenario for coal sees global coal demand close to its peak in the first half of the 2020s, but 10% lower by 2030.[29] Over the long-term to 2050, there are large reductions expected in global coal demand, ranging from 32% under stated policies to over 90% if the world transitions to net zero GHG emissions.[30] That said, it is very difficult to forecast future demand given the current uncertainty around policy settings in major economies.

Another top export commodity for Australia is liquefied natural gas (LNG) for which global demand will continue to be strong. The IEA estimates that LNG global demand will increase and it is expected to be concentrated in the Asia-Pacific region.[31] In particular, China is emerging as a fast-growing LNG importer, temporarily becoming the largest importer in 2021, before cutting back its imports substantially in 2022.[32]

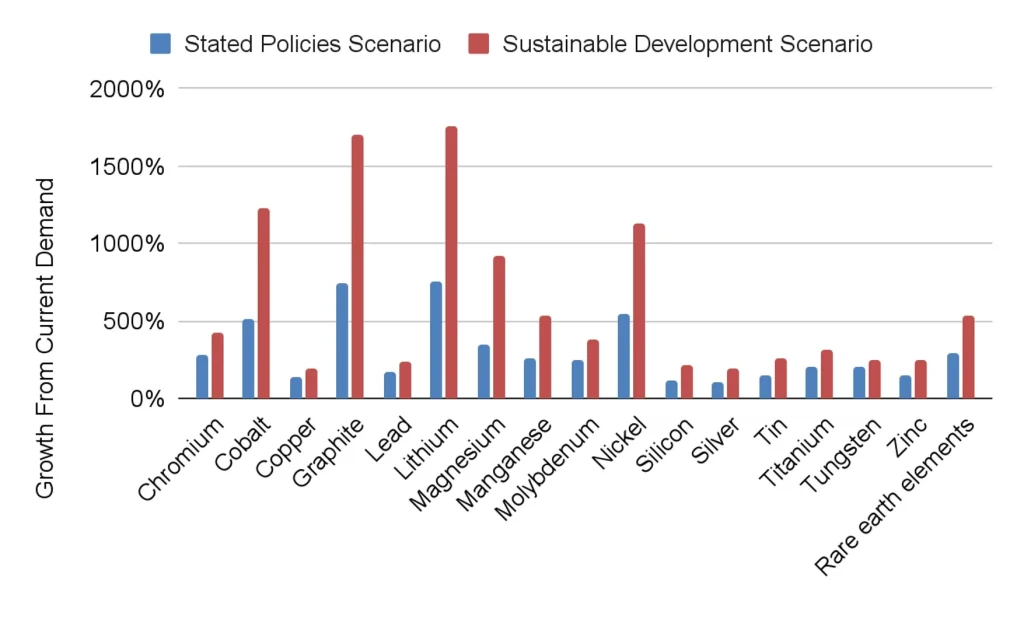

The global demand for many critical minerals, particularly nickel, graphite, lithium and cobalt is expected to grow strongly, partly due to their use in emerging technologies such as renewable energy and electric vehicles (Figure 9).

Figure 9. IEA forecasts of growth in demand for critical minerals from 2020 to 2030

Source: IEA, The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions (2021). Notes: IEA report is based on two main scenarios: i) the Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS), which is a pathway that fully achieves the world’s goals to tackle climate change according to the Paris Agreement, and ii) the Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS) which models current policies and energy sector plans.

The IEA estimates that demand for critical minerals will increase between three and six times as efforts increase to achieve net zero outcomes. To an extent, this growth will be supported by government policies favourable towards EVs and the transition to net zero. It is in Australia’s interest to reduce any regulatory burdens or additional costs that could hinder investment in the development of Australia’s critical minerals — e.g. the federal government’s counterproductive Closing Loopholes industrial relations regulations.[33]

Policy lessons

The appropriate way to profit as our community from our resources is up for ongoing debate, and there may be better ways. But we should not let the perfect be the enemy of the good, and we should recognise the large contributions to state budget coffers made by our current royalty regimes.

Based on the analysis in this paper, I suggest the following policy lessons.

- Royalties are a reasonable way to compensate the community for extracting non-renewable resources, all things considered.

- That said, improvements can be made to how Australians benefit from these resources:

-

- The Queensland government should revert to previous royalty rates for projects already in place before the 2022 royalty hike, to restore confidence in the stability of our policy settings. Generally, once a royalty regime is put in place by a government, it should not be changed for existing projects. Otherwise, doing so would be very bad for the investment climate.

- Further changes may be needed to the Commonwealth PRRT, given concerns that it is raising insufficient revenue relative to expectations.

- Norway is a special case. Norway was already a high-tax country with fiscal room to divert new oil and gas revenues to a sovereign wealth fund, whereas our state governments needed royalties to fund public services. The Norwegian strategy was highly risky, involving substantial state ownership through joint ventures with the oil and gas industry, which transferred risk to the state balance sheet and created corruption risks that could have led to the resource curse.

- State governments must get their fiscal houses to be resilient to the potential adverse budgetary consequences of decarbonisation if it is vigorously pursued. This involves moderating operating and capital spending and potentially seeking greater cost recovery and user charges for service delivery.

- Australia needs to address significant regulatory barriers in environmental approvals and IR to ensure its promising critical minerals industries develop, as royalties from them may be necessary to replace declining royalties from coal and gas.

Conclusion

Australia benefits substantially from its mineral resources. Our policy settings are not perfect, but there is no doubt our states are earning substantial sums from royalties. To some extent, this is at risk from various policy proposals.

Suppose Australian governments ban coal mining or gas extraction. In that case, they deny the community the opportunity to share in the wealth generated from extracting these valuable resources from the ground and selling them to a world market hungry for energy. Suppose we lose the revenues from these resources. In that case, state governments will need to increase other taxes, which will likely impose a greater excess burden on Australian taxpayers than royalties. This would constitute economic self-harm, particularly given that expectations of rapid global decarbonisation have proven overly optimistic. The International Energy Agency has reported that coal production reached a record high in 2024. Australia can continue to supply the world with coal, gas and mineral resources to meet global energy and manufacturing input needs. And if we do, the Australian nation and community will continue to benefit handsomely from the royalties.

Australians should be proud that we have avoided the ‘resources curse’ and have extracted as much value as we have. That said, we should not ignore the potential to improve our policy settings, potentially regarding the PRRT, which may not compensate Australians adequately for offshore oil and gas.

Endnotes

[1] Eslake, Saul (2024) “Distribution of GST Revenue: the Worst Public Policy Decision of the 21st Century to date”, https://www.sauleslake.info/distribution-of-gst-revenue-the-worst-public-policy-decision-of-the-21st-century-to-date/, accessed on 6 February 2025.

[2] https://www.qrc.org.au/media-releases/qld-govt-imposes-worlds-highest-royalty-taxes-on-resources-sector/

[3] Australian Government (2025) Budget Paper no. 1, Note 3: Taxation revenue by type, p. 291.

[4] The Commonwealth’s share of North West Shelf royalty revenue is based on the ‘Royalties’ estimate for 2024-25 in 2025-26 Budget Paper No. 1 (p. 293) of $918 million, less the ‘North West Shelf grants’ estimate in the WA 2024‑25 Government Mid-year Financial Projections Statement (p. ) of $551 million. The crude oil and condensate excise figure is from ATO Taxation Statistics 2021-22, Table 1: Excise and fuel schemes.

[5] Author’s estimate based on public sector workforce reports for the four largest states and ABS population data to scale up the total to a nationwide estimate.

[6] ABS, Schools, Australia, Table 51a In-school staff (FTE), 2006-2024.

[7] https://www.vu.edu.au/about-vu/news-events/news/research-shows-scrapping-inefficient-taxes-could-yield-nearly-1000-per-household

[8] Technically, coal, oil and gas are not minerals because of their biological origins.

[9] That is, the 15% marginal rate now only applies over $150-175/tonne.

[10] The effective royaty rates were calculated by the author as expected coal royalty ($/tonne) over the average price of premium metallurgical coal based on Department of Industry, Science and Resources and Queensland Revenue Office data.

[11] See AAP (2022) “Queensland government defends coal royalties after Japan’s ambassador raises concerns”, The Guardian Australia, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/jul/07/queensland-government-defends-coal-royalties-after-japans-ambassador-raises-concerns and Walsh, Liam (2023) “BHP CEO blasts Qld coal royalties in premier’s backyard”, Australian Financial Review, https://www.afr.com/companies/mining/bhp-says-queensland-investment-off-the-cards-after-coal-hike-20230623-p5dixi

[12] Evans, Nick (2022) “Glencore pulls plug on $2bn Valeria coal project in Queensland”, The Australian, https://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/mining-energy/glencore-pulls-plug-on-2bn-valeria-coal-project-in-queensland/news-story/e96fa1793065ad0db8e85b14781108a4

[13] KPMG Econtech, CGE Analysis of the Current Australian Tax System Final Report, 26 March 2010, p. 5.

[14] Ergas, Henry and Jonathan Pincus (2014) “Have Mining Royalties Been Beneficial to Australia?”, Economic Papers, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 13-28.

[15] Ibid, p. 23 and Australia Institute (2024) Australia’s small mining industry, https://australiainstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Explainer-Australias-small-mining-industry-Web-v3.pdf, accessed 29 January 2025, based on Foreign Investment and Trade Policy Division (2016) “Foreign Investment into Australia”, Treasury Working Paper, 2016-01, Chart 9, p. 7.

[16] Ergas and Pincus (2014, p. 23).

[17] Ker, Peter (2013) ‘Mining tax revenue slumps’, Sydney Morning Herald, 14 May 2013, https://www.smh.com.au/national/mining-tax-revenue-slumps-20130514-2jkm1.html#ixzz2TGVDRaYr, accessed on 17 March 2025.

[18] Kraal, Diane (2022) “[Budget Forum 2022] Why Not Repeal the Petroleum Resource Rent Tax and Levy a Royalty for Offshore Gas?”, Tax and Transfer Policy Institute, https://www.austaxpolicy.com/budget-forum-2022-why-not-repeal-the-petroleum-resource-rent-tax-and-levy-a-royalty-for-offshore-gas/, accessed on 17 March 2025.

[19] Jericho, Greg (2024) “A stronger PRRT cap: A fairer way to tax gas super profits”, Discussion paper, The Australian Institute, p. 11.

[20] Australian Energy Producers (2024) Key Statistics, p. 8, https://energyproducers.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/AEP_KS24_Web2.pdf

[21] Jericho (2024).

[22] Australian Government Budget Paper No. 1, p. 291.

[23] Cottarelli, Carlo (2012) “Fiscal Regimes for Extractive Industries: Design and Implementation”, Fiscal Affairs Department, International Monetary Fund.

[24] Reuters (2024) “Norway wealth fund hits record 20 trillion crowns”, Reuters, 7 December 2024, https://www.reuters.com/business/finance/norway-wealth-fund-hits-record-20-trillion-crowns-2024-12-06/.

[25] http://stats.oecd.org/OECDStat_Metadata/ShowMetadata.ashx?Dataset=REV&ShowOnWeb=true&Lang=en, accessed on 5 February 2025.

[26] Lee, David (2016) The Second Rush: Mining and the Transformation of Australia, Connor Court, Brisbane, p. 56.

[27] Llewellyn-Smith, David (2015) “Who is to blame for the East Coast gas cartel?”, Macrobusiness, https://www.macrobusiness.com.au/2025/01/who-is-to-blame-for-the-east-coast-gas-cartel/, accessed on 5 February 2025.

[28] Department of Resources, (2021), Queensland resources industry development plan, draft for consultation, State of Queensland.

[29] Reported in Queensland Treasury (2022a) Queensland’s Coal Industry and Long-Term Global Coal Demand, November 2022, p. 17; https://s3.treasury.qld.gov.au/files/Queensland%E2%80%99s-Coal-Industry-and-Long-Term-Global-Coal-Demand_November-2022.pdf

[30] Ibid., p. 21.

[31] International Energy Agency and Korea Energy Economics Institute (2019). LNG Market Trends and Their Implications. p. 2.

[32] Russell, C. (2022) “China to keep more LNG, but still buy less than last winter”, Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/china-keep-more-lng-still-buy-less-than-last-winter-russell-2022-10-18/

[33] Tunny, Gene (2023) Closing Opportunities, Not Loopholes: A review of proposed new laws regarding labour hire, casual employment, and the gig economy, Centre for Independent Studies, Analysis Paper 59 | November 2023.