Foreword

After an election result as sobering as May 3, 2025, there is a temptation to interpret the result as proof of permanent decline for the centre-right. Critics and commentators have been quick to oblige, sketching an obituary. But, as Tom Switzer outlines here, politics resists such certainties.

Events, and how political actors respond to them, shape the fortunes of political parties more than static ideologies or fashionable consensus. Time and again, history has shown how unexpected developments — whether economic shocks, leadership changes, global crises or opponents’ mistakes — alter the trajectory of governments and oppositions alike.

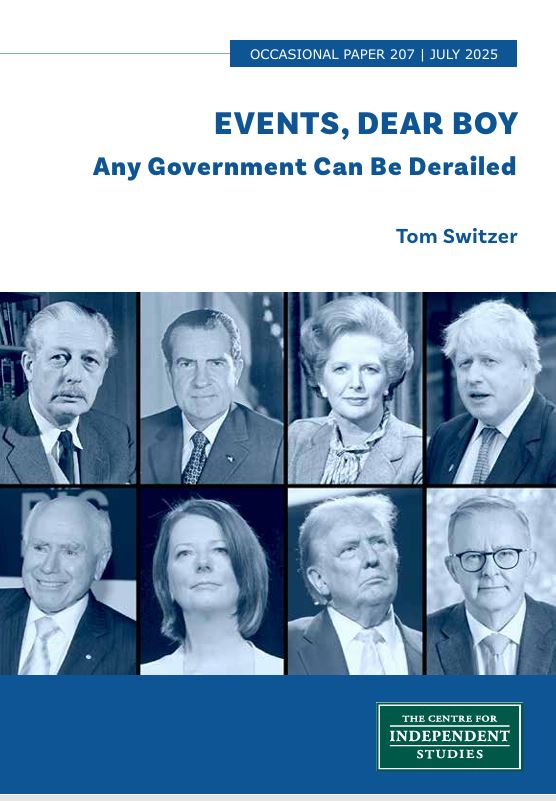

Former British prime minister Harold Macmillan’s oft-cited warning that politics is about “events, dear boy, events” has remained pertinent through the decades.

Australia’s centre-right today faces obvious challenges: declining support in metropolitan seats, alienation of younger and professional voters, ongoing competition from the Teals, and a Labor government that has cannily adapted to the public’s apparent demand for government paternalism.

Yet it is misleading to see this as a rejection of philosophical roots. The values that underpin centre-right politics continue to command public support. The problem is not that the ideas are obsolete, but that the ideas have not been forcefully and credibly re-articulated.

As Switzer points out, the pattern of politics — here and abroad — is cyclical. Governments that seem unassailable can quickly become vulnerable. Oppositions that appear moribund can be revived by a capable leader, a disciplined message, and the missteps of their opponents.

The paper also makes a valuable point about the ‘broad church’ nature of the Liberal tradition. Menzies’ genius was to unite conservatives and liberals with a common foundation: belief in individual freedom, enterprise, and the responsible management of government.

The global perspective is equally instructive. Whether in Britain, the United States or Europe, the ebb and flow of political fortunes reinforces the lesson that neither victory nor defeat is permanent. The Labour Party in the UK, written off in 2019, returned to power last year in a landslide – yet now is deeply unpopular. The Republicans in the US, seemingly buried by Obama’s 2008 victory, roared back just two years later as Donald Trump’s MAGA forces captured America’s centre-right party. Politics is a long game in which events can disrupt even the firmest narratives.

A party that wallows in despair will not be ready when events shift in its favour. A party that holds to its principles while adapting them to new circumstances and projects confidence in its own ideas will be better placed to seize the next political turning point.

This year’s election result suggests Australian voters may appear to support bigger government and an expanded care economy. But they might not be so supportive when the taxpayer bill finally arrives and economic growth disappoints.

Similarly, voters may support measures to reduce carbon emissions and to combat climate change. But they’re unlikely to welcome higher household electricity bills or the shutdown of energy-intensive industry.

In this respect, the argument that political predictions are as fragile as long-range weather forecasts should give pause both to critics who declare the centre-right’s demise and supporters who imagine an automatic recovery.

For those who care about the health of Australia’s democracy, this is more than just a question about a path back to government. A functioning two-party system depends on a competitive opposition able to hold government to account and to present itself as a credible alternative.

The Centre for Independent Studies has long argued that governments of any persuasion must be restrained — not only by the parliament and the media, but also by the ideas and scrutiny that come from outside government.

Switzer’s paper brings perspective to the present moment, sets the centre-right’s problems in a broader historical and international context, and offers a reminder that ideas and events — not fatalistic narratives — will determine its future.

Those of us who have watched Australian politics over decades have seen enough unexpected reversals to know the only certainty is change.

The challenge is to be ready when change comes.

Michael Stutchbury

Executive Director

Centre for Independent Studies

I Introduction

These are dark days for the Liberal Party of Australia. It has lost voters and members, and recent leaders have failed to reinvigorate its grass roots. Out of power across much of the country, the Liberals are dazed, demoralised, deeply divided and unsure about their future direction.

Since the 2025 federal election on May 3, many journalists and academics have written off the party of Robert Menzies and John Howard. By embracing divisive cultural issues, critics argue, Liberals appeal to a more insular section of the population. By alienating younger generations and professional women, they bleed votes to metropolitan progressive Independents. Unless they kick their conservative habits, the pundits keep telling us, the party will face a long time in the political wilderness.

Professor Mark Kenny reflected the consensus of many writers and intellectuals after the election when he told Sydney’s Sun-Herald that the Liberals are “risking terminal contraction” unless they “rediscover their progressive urban liberalism and own it very strongly”. According to Niki Savva on Radio National’s Late Night Live: “The Liberal Party is now dying, and that’s what the voters are telling them, that they are completely at odds with mainstream Australians”.

The Liberals certainly face serious challenges, and a key task new leader Sussan Ley faces is to appreciate the depth of her party’s difficulties. However, it is misleading to say the Coalition’s May 3 loss represents an outright rejection of conservatism. After all, on the battlefields of culture, border protection, national sovereignty and constitutional change, conservative and classical liberal ideas always compete and often prevail.

Not so long ago, in October 2023, voters easily rejected the Indigenous Voice to Parliament, which was part of the identity politics that has become a pre-occupation of global progressive movements. The referendum lost in all six states by a national margin of 60-40 per cent, even though the Yes campaign, with the whole establishment on its side, spent more than twice as much as the No campaign.

There’s also a danger in writing the Liberal Party’s political obituary. Politics is fickle, though pundits and academics all too often think it is static. Stuff happens: often it is stuff no one saw coming, let alone stuff they had discussed at the previous election. The supreme test of any political party or political leader is their ability to cope with the unexpected.

“The apparent hegemony of any political party is always largely illusory,” warns UK political scientist Philip Cowley. Political leaders make mistakes, and when they do — and they always do — capable opponents, with a sound public-policy agenda, can exploit the moment. This is especially so at a time when trust in government, and in the people and institutions of public life, is at an all-time low and when volatile voters across the western world are more willing to change parties. What the electorates give, they can take away.

The purpose of this paper is to put the Liberal Party’s political problems in a broader historical and international context and suggest that the media narrative about its troubles is as old as it is overstated. History shows that what appears to be certain can only come unstuck and what’s down can only go up. No victory or downfall is permanent in a democracy. Ideas matter. Decisions have consequences. As American commentator John Podhoretz argues, “people are not paying attention in real time, the way pundits do, but they do get a sense of things over time”, and their attitudes change when the circumstances change.

For example, after Sir Keir Starmer’s landslide victory in the British general election last year several respected commentators in Westminster said Labour would be in power for 10 or 15 years. One catastrophic year later Labour has crashed in the opinion polls, and were an election held tomorrow it would be lucky to come third. Poor decisions taken over the year have had their consequences, and there is a vacuum of good ideas.

But one cannot predict where events will go next: a capable opposition can leave a limping government dead and buried, or that government can have a change of fortune, or change of leader or face an external event, and win back support. In Australia, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese looked finished after the referendum landslide defeat. Just over 18 months later he had a resounding election victory.

Yet, despite what happened on May 3, the Liberal Party can bounce back: it needs ideas and someone bold to articulate them, and the Labor government needs to make errors. In politics it is rare that a major party is finished for ever. (In Britain, for example, it last happened with the riven Liberal party in 1918, and in Australia with the United Australia Party in 1945 when its members joined the new Liberal Party.)

The point here is that parties and leading political figures can rebound from the depths of despair. It’s the nature of politics to experience highs and lows. The worst thing defeated parties can do, even after a humiliating election loss, is to wallow in despair. If a defeated party gets off its knees, says what it believes in, and awaits ‘events’ to take their inevitable toll with the government, things can change rapidly — as history relates around the democratic world.

II Time and Chance

Around 60 years ago, two British prime ministers summed up the unpredictability of politics, and why the governance of any democracy is so dependent on what a third, Jim Callaghan, called “time and chance”.

Harold Macmillan, who was in Downing Street from 1957 to 1963, apparently spoke of “events, dear boy, events” when referring to the power of circumstances to derail a government or even an opposition from the course it thought it was on. No-one has yet found a definite source for that quotation, but Macmillan never denied saying it.

His successor-but-one, Harold Wilson — prime minister from 1964 to 1970 and then again from 1974 to 1976 — said: “A week is a long time in politics”. Again, the timing is uncertain, but Wilson claimed credit for the phrase. It is thought he minted it at a press briefing during one of the many Sterling crises that punctuated his first administration.

The notion had been apparent certainly since 1945, when Winston Churchill, as a great war leader who defeated Nazism, was supposed to win a general election. But he lost that year’s election to a socialist in one of the biggest landslides in British history. This was partly because the Conservative party was blamed for appeasing Hitler before the war, but also because of war weariness, not to mention a random and foolish remark Churchill made during the campaign about the Labour party resembling the Gestapo.

Even Tony Blair, who won three elections on the trot in 1997, 2001 and 2005, was not immune to the kind of events that damage political leaderships. There is a famous scene in the Oscar-winning film The Queen where Queen Elizabeth II, played brilliantly by Helen Mirren, tells the young and hyper-confident Blair that political circumstances can change “quite suddenly, and without warning”.

The scene was set a few months after the 1997 general election, when Blair led a united party to a landslide victory over John Major’s catastrophically divided Tories, and the prime minister was the hero of the hour: having captivated the British electorate, he captured the moment of Princess Diana’s death by lamenting the passing of “the people’s princess”. But six years later, Blair presided over a deeply unpopular war and was given the pariah treatment in his own country. No modern British prime minister at that time had left office more disliked and distrusted.

Events taking their toll is not, of course, unique to the British political arena. In the period since the Second World War, many events explain the highs and lows of politics.

Think of the dismissal of Gough Whitlam in 1975: in response to the Opposition’s decision to use its Senate control to block supply bills, the governor-general Sir John Kerr sacked the Labor prime minister to break a parliamentary deadlock. Or think of Whitlam’s distant successor Malcolm Turnbull, despite the weight of fashionable opinion behind him, losing his party’s leadership in 2009 and then 2018 over climate and energy policy; making him the only federal political leader to be dumped by his party twice (see Chapter IV).

Think of France. The seemingly unassailable Charles de Gaulle was forced out by his failure to react confidently to his country’s 1968 student protests (something the French refer to, appropriately, as les événements, or ‘the events’). Or think of François Hollande, who lost office in 2017 after some comic exposure in the media, notably of his riding secretly around Paris on a moped to visit one mistress while living with another.

Think of the US, which has a rich tradition of politicians benefiting from, or succumbing to, events. Lyndon B. Johnson was catapulted into office after the assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963 while Richard Nixon was catapulted out of it by the Watergate scandal in 1974. In 1972 he won 49 out of 50 states and 61 per cent of the popular vote. No Republican had ever won the presidency by so large a margin; no president had ever carried so many states. Democrats were demoralised.

Yet in less than two years, Nixon left the White House in greater ignominy than was ever suffered by a departing American president and two years later a little-known peanut farmer and Democratic governor from Georgia named Jimmy Carter won the White House. (Intriguingly, on the morning after Nixon’s sweeping re-election, the leading conservative polemicist William F. Buckley predicted that Nixon “could suffer the fate of Harold Macmillan, who in 1959 won the most triumphant re-election in modern English political history, and 18 months later everything lay in ruins about him.”)

Take George H. W. Bush. After America’s Gulf War victory in early 1991, his approval rating was so high — at 89 per cent — that bookmaker Ladbrokes made him the red-hot $1.25 favourite for re-election. For the rest of the year, pundits from left to right predicted doom and gloom for the Democrats, who had been out of the White House for a dozen years. “No serious Democrat has yet volunteered for the likely suicide mission of running against George Bush,” editorialised the U.S. News & World Report. “Many [Democratic] rank and filers privately concede 1992 might already be hopeless. For them, the real campaign is 1996.” In August 1991, a Chicago Tribune headline splashed: “Bush appears invincible for election”.

Yet Bush’s popularity leaked away as Americans confronted a recession and the polarising events of 1992, such as the Los Angeles riots. At the same time, a Texan billionaire named H. Ross Perot ran as an Independent presidential candidate, scoring about 19 per cent of the vote and hurting Bush’s re-election prospects. As a result, the war hero with the most-decorated presidential CV convincingly lost the 1992 election to a little-known, philandering, dope-smoking, draft-dodging governor of a small, poor, backwater southern state named Bill Clinton.

Then there is Barack Obama. With his resounding presidential election victory in 2008, taken together with the Democrat’s super-majorities in the Senate and the House of Representatives, the overwhelming consensus was that the moment represented a historical realignment of the American political landscape. The new demographics — most notably, rising minorities and the young — would bury the party of Abraham Lincoln and Ronald Reagan far into the future. Obama had declared Reagan was historically consequential and Bill Clinton was not; and he, Obama, intended to be the Reagan of the new liberalism.

Pundits agreed. American conservativism was dead, wrote leading journalist Sam Tanenhaus. According to columnist E. J. Dionne, the GOP was becoming a regional party of the South whose appeal was confined to marginalised angry white men. A Time magazine cover declared Republicans an “endangered species”.

However, as John Podhoretz pointed out in a review of Tanenhaus’s 2009 book, The Death of Conservatism — published several months after the original essay on which the book was based — it quickly turned out that American conservatism was no more dead than American liberalism was in 1981, when Reagan won the presidency, and the Republican corpse was no colder than Bill Clinton’s was in 1994 when the ‘Republican Revolution’ brought Newt Gingrich’s revolutionaries of the Right into the red-hot centre.

By the 2010 midterm congressional elections, Democrats had copped what Obama called a “shellacking”, the Republicans regained Congress and stymied his legislative agenda and, notwithstanding Obama’s re-election in 2012, his presidency was hardly the consequential one he and his admirers had predicted. That did not stop pundits (including this writer) from predicting Hillary Clinton’s return to the White House. But they had not counted on one Donald Trump to disrupt proceedings. Indeed, his upset victory in 2016 — itself a response to several events of the previous decade (the ‘forever wars’, the Great Recession, Hillary’s candidacy) — was the ultimate repudiation of Obama’s liberal agenda.

When Trump left office four years later, his approval rating was 34 per cent, according to Gallop, and like all defeated presidents since Grover Cleveland in 1888, he was ripe only for the history books. After all, he had refused to accept defeat by Joe Biden and appallingly tried to overturn the 2020 election. And most of his hand-picked House and Senate candidates were defeated in the 2022 midterm elections.

And yet Trump defied the odds and rebounded from serious setbacks, including an assassination attempt, to make the first presidential comeback from a re-election loss since the late 19th century. His shock victory was partly because Democrats and their media mates tried to cover up Biden’s evident flaws and pursue an unprecedented campaign of criminal and civil litigation against Trump, which backfired in the court of public opinion.

But the victory was also because Democrats had wilfully misinterpreted their small majority in 2020 as a mandate for left-wing progressivism. As a result, the chaos of a dysfunctional immigration system spilled into neighbourhoods. Crime shut down cities where officials refused to enforce laws. And massive post-Covid spending splurges wasted tax dollars and led to a surge in inflation that shrank real wages. The much-touted Biden transformation was not to be.

Even the most stable polities undergo the horrors of coping with events: look at how rickety Germany has become after decades of steady rule by Helmut Kohl (1982-98) and Angela Merkel (2005-21). Olaf Scholz, Merkel’s successor, lasted just three-and-a-half years before his coalition collapsed, as Germany’s economic performance dwindled; and his successor, Friedrich Merz, after several months of chaotic uncertainty, has a tenuous hold on power.

The European Union, of which Germany is supposedly kingpin, began to suffer more from internal disputes after a key ‘event’ — the surprising decision (to the political class, at least) by the UK to leave the organisation in 2016. And, indeed, all of Europe is on permanent alert for the latest caprice of President Trump, whose random threats to impose or rescind tariffs, or to reduce his country’s commitment to NATO, have created a form of chronic, and needless, instability.

Britain endured something similar from 2019 to 2022 during the bizarre prime ministerships of Boris Johnson and, for just 49 days in which she completely lost control of events, Liz Truss. In both cases, the damage was self-inflicted: Johnson by his lies and failure to attend to detail, Truss by her belief that she was more powerful than the global markets.

Sometimes, the fate politicians endure is just: sometimes it is not. But in a democracy, where the maintenance of public support and confidence are paramount, life is like that. But the idea is a two-way street.

Churchill was back in Downing Street in 1951 after the failure of the Attlee administration. Ditto Wilson in 1974 after the failure of the Heath administration.

LBJ secured his presidency through events, and within a year won an election in 1964 to confirm himself in office. But then he came unstuck, not least because of the Vietnam war, which turned public opinion against him as victory became more unlikely, and bloodshed rose. Having previously appeared unstoppable, Johnson did not even bother to fight the 1968 election.

Nixon lost the 1960 presidential election and failed to become governor of California in 1962, at which he famously told journalists: “You don’t have Nixon to kick around anymore because, gentlemen, this is my last press conference”. It wasn’t. He recovered, reunited a shattered and fractured GOP, and in 1968 won the White House at a time of widespread social unrest and war abroad.

Intriguingly, in 1965, when virtually no seasoned observer of U.S. politics thought he had a political future, Nixon encouraged his Australian friend Robert Menzies to write a book on “the exciting mystery of how so many of the world’s great leaders have had their most productive years after suffering shattering defeats”.

Menzies would know. He had led a minority government from 1939 to 1941 before he lost his party’s leadership. Widely denounced as aloof and imperious, ‘Ming’ went to the backbench and helped create the Liberal Party, which he led in opposition. By decade’s end, Menzies won power — and the next six elections — to become Australia’s longest-serving prime minister. In 1966, he was unique among political leaders in that he retired at the peak of his power and a time of his choosing.

Another great British politician, Enoch Powell, famously said (and we do have a source for this: he wrote it about Joe Chamberlain, the legendary 19th century statesman): “All political lives, unless they are cut off in midstream at a happy juncture, end in failure, because that is the nature of politics and of human affairs”.

Politics and human affairs cannot be other than contingent upon ‘events’. Whether it’s man-made or an act of God — an economic downturn, a natural disaster, a terrorist attack, a foreign crisis, a global pandemic, a mistake, or an act of brilliance on the part of the opponent — political parties and their leaders are judged by how adroitly or incompetently they cope with the unexpected. No victory lasts forever, and no downfall is permanent.

III Politically Mortal Blows

Macmillan, who apparently identified the phenomenon, was profoundly demoralised after the general election defeat in 1945. He had lost his seat and predicted the Conservative party was finished. Two years later, economic crisis changed the face of British politics and thereafter it was downhill all the way for Clement Atlee’s Labour.

Macmillan eventually took over as prime minister in 1957 and during his first three years in Downing Street he seemed to be supreme. He told the British people that, with low unemployment and improving living standards, they had “never had it so good”. He had rebuilt the Tories after the Suez crisis of 1956 and had mended the fractured relationship with Washington. As a result, he won a thumping election in 1959, which saw the conservative majority increase from 60 to 100 seats.

However, beneath the surface were increasing signs of major difficulties. Macmillan favoured ministers with whom he felt comfortable — those who deferred to him or aristocrats on whom he fawned — and these people were mostly second-rate. As a consequence, his administration made inept mistakes, notably in economic and foreign policy, and became seen as increasingly out of touch.

Then two politically mortal blows struck him: the John Profumo scandal, in which his war minister admitted sleeping with the former mistress of a Russian diplomat at the height of the Cold War, and which Macmillan hadn’t suspected. He and his colleagues wildly mismanaged the issue. Then, in a final twist of fate, Macmillan had prostate trouble, thought he would die (he lived another 23 years, into his 93rd year), and precipitately resigned, creating the impression of a shambles.

By 1963, Macmillan was in deep political trouble that no one would have seen coming after his election victory four years earlier. Arthur Schlesinger, John F. Kennedy’s special assistant, was visiting London in March of that year and he caught the significance of the brewing political crisis in a report to the president:

“The Conservative government is in a sad state. It has held power longer than any government in modern British history (it is now in its 13th year), and it has run down dreadfully. Its solid achievements are largely forgotten. People are bored with it and fed up with it… Today that government can do nothing right. It seems hopelessly accident-prone. It is detested by most of the press. It is derided on radio and television. Comedians make savage jokes about it. It sinks steadily in the public opinion polls under the weight of old age, unemployment, Soviet espionage, the Common Market failure… and personal scandal. It reeks of decay; and the press and the opposition, sensing a rout, are moving in for the kill… it is hard to overstate the atmosphere of political squalor in London today… [and] the impression that the government is frivolous and decadent, and that everything is unravelling at the seams.”

By the northern autumn of 1963, Macmillan’s government was in meltdown and, as his biographer Charles Williams noted, “his language, the way he dressed, his shuffle, his affectations, all made him seem even more of an anachronism than was truly the case”. Macmillan was turning into a standing joke with the public, and once a political leader reaches that stage, there is often no hope of redemption.

It was a sad end to Macmillan’s premiership after such a promising start, and he was replaced by Alec Douglas-Home who lasted in Number 10 for just a year before a change in government. The crisis damaged the notion that the Conservatives exist indefinitely as ‘the natural party of government’. But it reaffirmed an iron rule of politics that when you reach the top, you can’t — at least, in a democracy — stay there.

IV Australian Stability and Turmoil

Perhaps nothing better demonstrates Macmillan’s dictum than Australian politics. It is often remarked that, until the past two decades, post-war politics were marked by periods of long, stable governance, from Robert Menzies through to John Howard. Indeed, in the 23 elections from 1949 to 2004 Australians had changed governing parties only four times. But even during this period there were at least two elections that upset expectations.

One of them was 1975. After the Coalition lost power in 1972, Gough Whitlam set out to transform the political and public-policy landscape. During the next two years, the Liberal Party had barely registered a pulse under Billy Snedden. It was widely believed that Labor would be in power for a very long time and that in the Liberal party room small-l liberals should and would prevail over conservatives (as he then was) such as Malcolm Fraser.

To demonstrate the point, Menzies became so disillusioned with his successors that it’s unlikely he voted Liberal in the early-to-mid ’70s, preferring to vote for the anti-communist Democratic Labor Party instead. “The idiots who now run the Liberal Party will drive me around the bend,” he privately lamented in 1974. “The so-called little-l liberals who run the Victorian Liberal party believe in nothing but still believe in anything if they think it worth a few votes. The whole thing is quite tragic.” He saw Snedden as, among other things, “politically, an idiot. He always says the wrong thing, at the wrong time”.

Yet within the year, Fraser came from nowhere to, first, defeat Snedden in the party room, then win the largest-ever majority in the House of Representatives — only to repeat the landslide two years later, in 1977. The widely-heralded era of Whitlamism had lasted just three years.

Similar prophets of Liberal doom appeared in 1993. The Coalition went into the March election with a good lead in the opinion polls and a widespread expectation that its leader John Hewson would defeat the ten-year-old Labor government. The arrogant Paul Keating had replaced the popular Bob Hawke and Australians were experiencing Keating’s “recession we had to have”, with unemployment rising to 11 per cent.

Yet, in the face of Keating’s ferocious assault on the Coalition’s free-market policy agenda, which included a goods and services tax, the Coalition lost what the press had dubbed ‘the unlosable election’. There was a 5.5 per cent swing to Labor and the Liberals lost six House seats. At the time, most people thought the Coalition was going to triumph.

However, with Labor’s shock victory, attitudes changed so rapidly that it was fashionable to write off the Coalition. Historian Judith Brett declared: “The Liberal Party in the 1990s seems doomed”. A year later, in 1994, NSW Liberal senator Chris Puplick warned the party was “still seen as exclusionist, hostile to new ideas and new people and too concerned with trying to bring back the ‘good old days’”. Yet within two years, the Liberals annihilated Keating’s government and, along with the National Party, stayed in power for about a dozen years.

John Howard was a politician of unusual talent, based on a serious intelligence and a powerful grasp of history and public policy. He also embodied the Arnold J. Toynbee theory of ‘departure and return’: the idea that consequential leaders must endure time in the political wilderness before returning to power.

After his colleagues conspired to end his Liberal Party leadership in 1989, Howard accepted that any comeback would be “like Lazarus with a triple bypass”. Five years later, in 1994, he conceded, again: “I accept completely I’ll never be leader of the Liberal party again. It’s out of the question”. Yet within two years, in response to fatal mistakes made by the then Opposition leader, he reclaimed his party’s leadership before winning the 1996 federal election in a landslide.

It may have been fashionable to revile ‘Little Johnny’ in the self-satisfied senior common rooms of Australia’s universities: he was compared to Hitler, and analogies were drawn between post-Keating Australia and pre-Mandela South Africa. But he was widely respected across the rest of the country.

As a result, Howard had established himself as more than a mere politician. He was the leader of the nation, a position from which it was far harder to be dislodged. That success was partly a function of the settled will of the voters, who had decided in 1996 that, after 13 years in exile, the Coalition would be given a proper turn at government, which meant at least two terms (even though the 1998 election was exceedingly close).

But it was also a function of a specific event which, just a few weeks after the election that brought him to the Lodge, seemed to confirm his tenure of it. It was the Port Arthur massacre and the remarkable weeks that followed when his government legislated national gun laws.

Even when he was counted out, Howard somehow bounced back to flatten his opponents, as he did most notably against Kim Beazley in 2001 and Mark Latham in 2004. For the former, the events that changed the political weather in Howard’s favour were the Tampa asylum-seeker standoff and the September 11 terror attacks (though Howard has always maintained his government’s comeback had already begun as evidenced by his party’s strong showing at the Aston by-election on July 14). For the latter, it was his opponent’s cosy relationship with the Greens over logging of old-growth forests in Tasmania, which came at the expense of Labor’s historic blue-collar constituency.

By 2006, Howard had presided over 10 years of unprecedented prosperity and the Liberals were on top of the highest mountain while the Labor Party sunk in the deepest valley. The Wall Street Journal editorialised: “Somewhere, Ronald Reagan is smiling”. But trouble loomed. Public doubts intensified over his government’s industrial relations changes and his refusal to pass the torch of Liberal leadership to the next generation.

By late 2007, Howard lost power to Rudd who, unlike his Labor party predecessors, mimicked his opponent’s agenda — and Howard lost the very seat he had held for nearly 35 years. Although his critics underestimated his capacity to connect with the Australian people and his incredible reserves of determination, Howard could not defy the Powell doctrine that all political careers end in failure.

The media consensus then was that Kevin Rudd could consign conservatives to “exile for a very long time indeed” (Michelle Grattan), much as American pundits would soon predict Obama’s victory would mark a liberal realignment of the U.S. political landscape. And for a while, things did indeed look dire for the Coalition. For the next two years, the Liberal Opposition, led first by Brendan Nelson and then Malcolm Turnbull, could not lay a glove on Rudd. Labor consistently remained ahead of the Coalition in the opinion polls by double-digit margins. It was against this backdrop that many pundits insisted the road to Liberal salvation was paved with progressive intentions (from refugees to reconciliation to re-regulation of the labour market to decarbonising the economy).

For two years, the climate debate had been conducted in a heretic-hunting and illiberal environment. It was deemed blasphemy for anyone to dare question the policy consensus to slash carbon emissions. Rudd claimed that climate change was the “great moral challenge” of our time and denounced critics of his keynote emissions trading scheme legislation as “deniers” and “conspiracy theorists”. With opposition leader Turnbull, Rudd hammered out legislation to put in place an emissions trading scheme (ETS), but the Coalition was bitterly divided.

In mid-to-late 2009, the media mantra was that opposition to Labor’s ETS would badly burn the Liberal Party. “The Liberals will face humiliation at the polls” (Laurie Oakes). They will be “signing their own political death warrant” (Paul Kelly). They need to “get the climate change issue as much off the election agenda as possible” (Michelle Grattan). “The party faces electoral oblivion” (Peter Hartcher). According to The Australian’s front-page [November 28, 2009]: “The Coalition faces an electoral wipeout [of at least 20 of its metropolitan seats] at next year’s federal election if the rebels led by Tony Abbott and Nick Minchin succeed in blocking the government’s climate change legislation”.

Then, two events in December changed the political landscape profoundly. First, Abbott, whom his critics had marked as a right-wing throwback to a bygone era, narrowly defeated Turnbull in the party room. His strong opposition to the ETS meant that he would be “electoral poison” (Laurie Oakes) and lead to “the destruction of the Liberal Party”. the general public’s impression steadily grew that the PM According to historian Judith Brett: “The Liberals risk becoming a down-market protest party of angry old men in the outer suburbs”. The second event that upended Australian politics was the Copenhagen climate summit, which spectacularly failed to reach a legally binding, enforceable and verifiable global pact.

Suddenly, Rudd imploded, his stratospheric poll figures cratered and, without missing a beat, the same media pundits who had previously denounced Abbott as unelectable changed their tune. Opposition to Rudd’s ETS was now a political godsend for the Liberals. The government was “very worried,” it’s in a “mess” and on the “defensive” over its ETS (Oakes). Abbott had “stolen the march” and “Labor’s policy is in trouble” (Kelly). For Labor’s marginal seat holders, the ETS was “becoming something of a nightmare” (Grattan). A poll in early February 2010 vindicated “the politics of the Coalition’s decision to argue with Rudd rather than agree with him” (Hartcher). Within a few months, Rudd ditched his signature legislation.

Rudd was in trouble on other fronts (namely, his mining tax and his diluted border protection position) and his deputy Julia Gillard, backed by Labor factional warlords, toppled him in a premeditated and ruthless coup that had all the hallmarks of a Shakespearan tragedy, though without the satisfaction of its literary qualities. Undeterred, Abbott continued his relentless attacks on other key issues of principle and policy.

For the next three years, Rudd tormented his successor Gillard persistently like Banquo’s ghost. Her approval ratings fell to unprecedented levels. The result was that the assassin herself was fatally knifed — by the very man she backstabbed a few years earlier — and Abbott handed the Australian Labor Party one of its biggest defeats in 2013.

No member of the Canberra press gallery foresaw Abbott’s election as Liberal leader in December 2009. But it is a fair bet that the event triggered Labor’s leadership crisis, which culminated in the downfall of three prime ministerships. In office, though, Abbott made several self-inflicted mistakes, and he was eventually dispatched by Turnbull, whose trick was to appeal to voters who didn’t much like Liberals.

There was, to be sure, a real sense of excitement about politics, at least among the metropolitan sophisticates. The Sydney Morning Herald columnist Elizabeth Farrelly predicted: “Malcolm — who like Beyoncé is known universally by his first name — will be the longest-serving prime minister since Menzies. Possibly ever”. In an echo of Macmillan’s declaration in 1957 that Brits had “never had it so good,” Turnbull declared: “There’s never been a more exciting time to be an Australian”.

But the trouble for any politician exciting high expectations is that they can almost never be fulfilled. And no Australian politician in recent times had ever excited such expectations as Turnbull. His gifts of intelligence and image management did a terrific job in winning the Liberal leadership. They were of less use in governing; especially in the relentless digital media cycle when every setback and error is magnified.

Conventional wisdom predicted a big Turnbull victory at the 2016 federal election, but his double dissolution was a spectacular miscalculation. He lost Abbott’s massive parliamentary majority, came within a seat of losing power and became a prisoner of his party more than ever. Against expectations, Turnbull, who at first seemed so capable and confident, came to resemble Rudd in the first half of 2010: adrift, vacillating and at the mercy of events. As a result, the general public’s impression steadily grew that Turnbull had lost his way, his enemies circled, and he, too, was dumped in favour of his treasurer Scott Morrison.

For months leading up to the next election, in May 2019, the polls and betting markets pointed to a convincing Labor victory. The press gallery said Morrison couldn’t possibly win: the evangelical ‘coal-cuddler’ was the wrong man for his times. Morrison was steering the tour bus “into the electoral abyss,” warned a Sydney-based Young Liberal president in The Age. “With each poll and each blunder, the Morrison government’s chance of re-election becomes fainter and fainter and we only have the insurgents and their petty hatred of Turnbull to blame.”

Yet the 2019 election went down as the most dramatic failure of discernment in the history of Australian punditry. During the previous three years, social-media outlets created a climate of opinion in which it was politically incorrect to oppose identity politics, high taxes, wealth redistribution and costly climate-mitigation policies. In the privacy of the voting booth, though, what Morrison had called “quiet Australians” decided that their interests lay in a low-tax and resource-rich market economy.

Morrison’s path to victory was about as narrow as Trump’s road to the White House in 2016. But he was helped by his opponents’ lurch to the left. The Labor Party, which with the crucial help of the Coalition did much to deregulate the Australian economy in the 1980s, was now pledging high taxes on property investors, self-funded retirees and high-earning wealth creators. In the name of reducing inequality, Labor wanted to raise government obstacles to the kind of risk-taking and hard work that allowed many Australians to climb the income ladder so rapidly. But then after the Covid crisis, which admittedly would have challenged the capacity of any government to cope, Morrison lost power to Anthony Albanese in May 2022.

It is difficult to review the past two decades of Australian politics without understanding the important role events have played in upending orthodoxies. From Howard’s come-from-behind victories and defeat in the 2000s and Abbott’s rise later that decade to Turnbull’s falls in 2009 and 2018 and Morrison’s election in 2019, political assumptions were turned on their head and most journalists and academics were caught unawares. The lesson: political predictions, especially years before the next election, are as reliable as a 12-month weather forecast.

V Fighting the Battle of ideas

All governments need to be curbed. The task of restraining the Albanese government will fall on parliament and the media. Most of all it will fall on what Macmillan referred to as ‘events’ and how the Prime Minister and his opponents respond. Yet for Albanese, events in the lead-up to the May 3 election conspired to reinforce his position.

At the beginning of the year, betting markets pointed to Peter Dutton becoming prime minister. Polls showed Labor could lose its majority, perhaps even power outright. “Labor’s chances look wafer thin,” predicted John Black, former Labor senator and the Australian Financial Review’s election expert. Polls showed Labor’s “policy assaults have not been enough to turn the tables” on Dutton, warned the Sydney Morning Herald’s David Crowe. “The Government is on course for defeat,” he added.

But then the election was overtaken by events. The biggest was the tariffs imposed by the Trump administration not only on rival powers such as China, but also on loyal allies such as Australia. Taken together with Dutton’s poor campaign, the first interest rate cut in over four years and a cost-of-living crisis that jolted voters into supporting the party of big spending, the disruption pushed voters towards Labor. Add to this that the tide of history was against an Opposition victory — only one federal government has lost power after one term since 1901 — and the election was a reminder that Australians are a temperamentally conservative lot, wary of change and hostile to radical and disruptive change.

Exit pollsters, who failed so dismally to predict the result, made some telling discoveries. Many voters admitted their unhappiness with Albanese and confessed to great economic hardship — two issues that ordinarily would be enough to defeat an incumbent. But these voters still backed Labor, because it reflected something they regarded as even more important: a strong safety net during a cost-of-living crisis and a time of Trumpian disruption. But the Coalition never mounted a counter argument.

It is true that tax cuts alone would not have restored the party to power. But to argue during the recent campaign that lower taxes and spending restraint should not be at the heart of the party’s programme was to sell the pass to Labor. While the left side of politics wants to expand the size and scope of government, Liberals should seek to shrink it to the point that wealth and power can be returned to the people, and they can be left to plan their own lives. If the Liberals do the opposite and try to copy Labor’s spending increases to bribe voters, they will walk straight into their opponent’s trap, as they did at the last federal election.

Many commentators argue that the redemption of the Liberal Party lies in the ‘political centre’. By that, they mean it should stop waging culture wars and ape Labor’s net-zero climate agenda. But the shift to renewables needs to be approached with far greater caution. As Tony Blair has warned, politicians should face the “inconvenient facts,” which show that any policy based on phasing out fossil fuels was “doomed to fail”. It’s wrong, he warns, that people are “being asked to make financial sacrifices and changes in lifestyle when they know that their impact on global emissions is minimal”. The right goal should be to the pace of change, not to its long-term necessity.

As for Liberals ‘waging a culture war’, what the pundits mean here is that it’s fine when progressive elites advance their cultural agenda with new ideas and rules — often via the least representative and accountable institutions (such as diversity, equity and inclusion bureaucracies) — but resisting this agenda is an act of aggression.

Many on the left shout ‘culture war’ to avoid debate. They don’t wish to engage in what is another way of saying the battle of ideas, because they sense, rightly, that the Australian people would not support their views on values and culture. The message of the Voice referendum — and the annual fracas over Australia Day — is that the Australian public is tired of it.

None of this is to deny the very real challenges that confront the Liberal Party; from attracting younger voters and preselecting more female candidates to raising money and stopping the haemorrhage of metropolitan voters to Teal Independents. Deep policy divisions are increasingly evident between Liberals and their coalition partner the National Party, from net zero and nuclear power to divestiture powers for supermarkets.

But parties of such long standing will survive as the main vehicles for those Australians who want a more secure nation, a smaller state, lower taxes, national sovereignty and a humane but strong national identity.

Historically, the Liberal Party has properly claimed to be a broad church; one capable of embracing both liberal and conservative beliefs. At its core, that means a commitment to individual freedom, productivity, educational opportunities, housing affordability, a dedication to a strong national defence, support for an inclusive civil society, a scepticism towards the taxing, spending, regulatory and privacy-shedding powers of a large, centralised government, and an insistence upon the prudent management of the people’s financial affairs.

Philosophical conformity within the Liberal Party has never been achievable or desirable. But as the Sydney Institute’s Gerard Henderson points out, every leader who has won power from opposition — Menzies, Fraser, Howard, Abbott — has hailed from the party’s centre-right tradition.

VI Looking ahead

If, as Harold Wilson said, a week is a long time in politics, a year is an eternity. Anything can happen in the next two to three years. Of course, it is very difficult now to predict a Coalition resurgence in the foreseeable future. But it was difficult for the Liberals on their own in 1993 to smash Labor in 1996 or Labor in 2004 to emerge victorious three years later. It seemed inconceivable in 2019 for the British Labour party to win the next general election, just as it seemed impossible in 1991 for the Republicans to lose the White House a year later.

When a government is under irresistible pressure from events, the fact that it has a big parliamentary majority is largely irrelevant. And an Opposition, however few in numbers, has an opportunity to exploit. It’s also possible, as history shows, that a government becomes so overwhelmed by hubris that it hastens its own destruction.

Harold Macmillan famously identified the worst threat to governments and political leaders as ‘events’. It is the unplanned and the unexpected that has made or, more often, broken governments and political leaders. But the British prime minister was only half right. It is not the events themselves that define a leader or government; it is how they respond to those events. The true test of any government or opposition is their ability to cope with the unexpected. Who knows what ‘events’ could challenge the Labor government between now and the next election and how the political leaders might respond?

Tom Switzer is a senior fellow and former executive director at the Centre for Independent Studies (2017-25). He has been a presenter at ABC’s Radio National (2014-23) and an editor at The Spectator (2008-14), The Australian (2001-08), the Australian Financial Review (1998-01) and the Washington-based American Enterprise Institute (1995-98). He has been published in the Wall Street Journal, New York Times, Financial Times and the New York-based Foreign Affairs.

The author would like to thank John Howard, Gerard Henderson, Simon Heffer and David Stevens for their comments and suggestions.