Executive Summary

- Fiscal rules are numerical limits to one or more of government spending, revenue, deficits and debt. Their use has become widespread in international practice. While there is evidence of their effectiveness, the conditions for success are demanding — not least that governments have a deep-seated, lasting commitment to fiscal discipline.

- Australian federal governments have a long but patchy record of using fiscal rules, which effectively ended with the onset of the pandemic in 2020. It has become a point of criticism by fiscal experts that there are currently no numerical fiscal rules and that fiscal policy is being conducted without the guardrails that can help prevent it from drifting into excesses of spending, taxation, deficits and debt.

- The purpose of fiscal rules is to signal a government’s commitment to fiscal discipline and to act as a bulwark against systemic biases towards over-spending and over-borrowing. They are a form of fiscal self-discipline on governments; akin to the surrender of political control of monetary policy to independent central banks working to an inflation target. In the case of fiscal rules, however, governments remain in control of the policy instruments.

- Australia needs a set of fiscal rules, first to help bring about consolidation of the fiscal position to sustainable settings, and second to maintain a stable longer-term equilibrium characterised by balanced budgets with lower spending, tax restraint and a shrinking debt burden. These rules are designed for the federal government but states also need their own rules.

- Specifically, this paper proposes for the consolidation period, which may last three to four years:

- The headline budget cash deficit to shrink to sustainable balance. (The shift from ‘underlying cash’ to ‘headline cash’ is designed to guard against current excessive resort to outlays that are not classified as ‘underlying’.)

- Total nominal payments growth not more than 2.5% a year until sustainable balanced budget is reached.

- Tax receipts not to exceed current forward estimates unless economic conditions prove more favourable to revenue, in which case all of the excess would be devoted to faster reduction of the deficit.

- For the post-consolidation long-term:

- Balanced headline cash budget result on average over the economic cycle, with surpluses as long as the economy grows at or above trend.

- Total nominal payments growth not more than 2.5% a year plus trend population growth plus trend productivity growth (likely 4.5-5.0% in total). This means that growth in real per capita payments is governed by productivity growth.

- Trend growth of tax receipts to be calibrated to the expenditure growth cap, with actual tax receipts in any year above or below trend depending on economic conditions.

- While there is no need for a separate debt rule, given the above, compliance would result in gross debt at face value shrinking as a percentage of GDP and the dollar value of debt also declining in years of budget surplus.

- These rules should be enshrined in legislation through amendment of the Charter of Budget Honesty and institutional changes made to enable effective independent monitoring and reporting of performance relative to the rules. This role should be carried out by the Parliamentary Budget Office operating under a widened charter.

- Compliance with these fiscal rules is the best contribution fiscal policy can make to macroeconomic stability and setting the foundations for productivity growth and commensurate advancement of real living standards.

Introduction

Fiscal rules are numerical limits to one or more of government spending, revenue, deficits and debt. Their purpose is to reinforce fiscal discipline against the political temptation for governments to spend, tax and borrow to excess. Australian federal governments have a long but patchy record of both adopting such rules and adhering to them.

There are currently no numerical fiscal rules and the government’s fiscal strategy consists of qualitative statements of intent. At a time of historically high levels of spending, tax revenue and debt, and significant deficits being projected well into the future, the absence of quantitative rules has been criticised by fiscal experts.

The purpose of this paper is to contribute to the debate on fiscal rules by discussing their nature and purpose, reviewing the history of their use in Australia and internationally, and proposing a set of rules suitable to the fiscal challenges of the times.

At the same time, it is emphasised that rules will only be effective in improving outcomes if the political will exists to do so.

What are fiscal rules?

Many policy considerations go into making a government’s budget; including social, defence and economic management. The term ‘fiscal policy’ refers to the overall design features including the size and future path of the budget balance (deficit/surplus); the level and future path of public debt; the overall level and growth rate of spending; and the overall level and growth rate of revenue, particularly its major component taxation.

These aggregate features of the budget may be considered just a by-product of decisions on the specifics of spending and taxation, but more typically the aggregates are themselves policy choices that feed back into what the government can afford to do at any point in time.

Fiscal rules are meant as a self-imposed discipline or set of constraints on spending, taxation, deficits and borrowing. Ideally, they are permanent or at least long-lasting and transcend changes of government. Rules may simply be announced as policy and set out in the budget documents, or cast in legislation, or even set in a country’s constitution, though that is rare.

In federal systems or where there is meaningful devolution of some fiscal powers, both national and sub-national governments may have their own fiscal rules. There may also be supra-national rules when a group of countries is closely integrated, such as the European Union.

When rules are adopted, they are often accompanied by institutional arrangements such as an independent ‘watchdog’ authority to monitor compliance with the rules and perhaps take a role in budget preparation and enforcement of the rules.

In summary, rules are meant to constrain one or more of overall deficits, debt, expenditure and revenue, may or may not be cast in legislation or the constitution, and may be supported by associated institutional arrangements.

The case for fiscal rules

Why would a government or parliament want to constrain its own fiscal freedom? It would seem politically irrational to do so. But that is what fiscal rules are meant to do.

The rationale for such self-discipline stems from the systemic biases towards over-spending and over-borrowing well-known in public finance literature. These biases are based, for example, in the political temptation to buy votes; the effectiveness of vocal and manipulative sectional interests against the docility of the broader public interest; the empire-building incentives for individual ministers and public servants; and the opportunity deficit financing presents for buck-passing to future generations.

A wise, far-sighted politician understands the hazards of fiscal indiscipline, that habitual over-spending usually ends badly, and that temptation is best put beyond their reach — and that of all their colleagues and successors. There is no way of completely neutralising these biases, but fiscal rules are a way of leaning against them.

There is a parallel with monetary policy and central bank independence. Ministers used to have a direct role in setting monetary policy. The temptation to set interest rates too low and monetary policy too loose to keep inflation in check is obvious. The long period of high inflation from the late 1960s into the 1980s and 1990s in some countries led governments — including the Australian government — eventually to give up their direct monetary policy role, make central banks independent where they weren’t already, and give them inflation targets. The political system could have kept control of monetary policy but opted for delegation and self-discipline by giving it up. This has for the most part stuck and is generally agreed to have been highly successful; although, alarmingly, such independence is now under challenge in the United States.

The parallel with fiscal policy is limited because monetary policy is narrower and more technical, although it does touch the politically sensitive issue of interest rates. Fiscal policy instruments, by contrast, embrace everything from tax rates to social benefits and defence, and as such inevitably involve political value judgements and trade-offs that cannot be delegated to an unelected body. This is why fiscal rules are limited to constraints on aggregate spending, taxation, deficit financing and debt, without attempting to specify the policy details behind the aggregates.

If fiscal rules are observed by policymakers, their contribution to economic stability can be substantial. Over time, they can also build a store of fiscal credibility that lowers borrowing costs, gives business greater confidence and predictability as a basis for investment, and gives governments more flexibility in responding to economic shocks. However, whether fiscal rules are actually effective depends on a range of factors, not least of which is the commitment of current and future governments to adhering to them. If governments adopt fiscal rules only as the latest policy fashion item but lack commitment to them, or if they are subject to chopping and changing, the rules will fail to achieve anything. There must be a deep-seated belief in fiscal discipline for rules to work.

Australia’s experience with fiscal rules

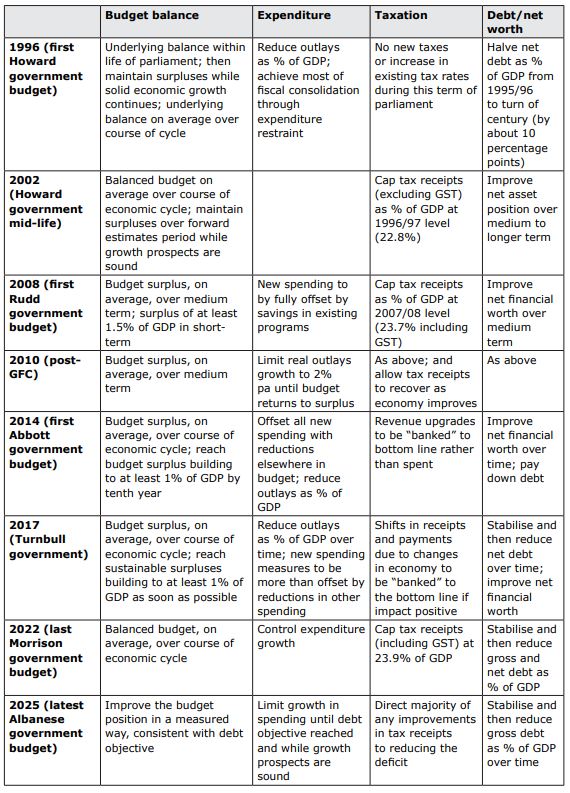

Australia has a long history of fiscal rules at the federal level from 1985, although the rules have sometimes been nothing more than short-term targets to adjust the fiscal position when it has become untethered from responsibility. Moreover, the rules were changed over time with changes of government and economic circumstances, whereas best practice calls for consistency over time.

With the exception of those noted, references for the history that follows can be found in the relevant Budget papers at budget.gov.au and in the Attachment.

The use of fiscal rules was abandoned during the coronavirus pandemic as government spending and deficits soared, briefly and loosely revived by the Morrison government in its 2022 budget, but then abandoned again by the new Albanese government in its first budget later in 2022. It remains the case in 2025 that there are essentially no fiscal rules, and only vague statements of strategic intent.

The details of fiscal strategy statements as spelt out in budget papers for selected years since 1996-97 are set out in the Attachment. Some of these qualify as fiscal rules, while others are short-term objectives or nebulous statements of intent. The Attachment does not list the Charter of Budget Honesty (CBH), which has had a constant presence since its enactment in 1998. The CBH is worthy legislation but is not a fiscal strategy statement and does not specify fiscal rules. It requires that governments articulate their fiscal strategies in budget documents and adhere to specified principles of sound fiscal management.[1]

Fiscal rules have also been used at the state level, but this paper is focused on the federal government experience.

- The fiscal trilogy of 1985[2]

In the mid-1980s the Hawke government faced the problem of historically high budget spending reaching above 27% of GDP and deficits of around 3% of GDP — partly of its own making and partly inherited from the previous government. In 1985 the government embarked on a fiscal adjustment articulated in what came to be known as the ‘fiscal trilogy’ because of its three parts:

- Not to raise tax revenue as a share of GDP (then 22.5%).

- To lower budget outlays as a share of GDP (then 27.5%).

- To reduce the budget deficit in absolute terms and relative to GDP (then 2.6%).

Thus, the emphasis was on government expenditure restraint rather than lifting the tax burden. The adjustment was mostly successful, partly because of the government’s restraint measures but also because the strong economy generated much more tax revenue, which led to the first constraint being breached. Outlays contracted sharply not only as a share of GDP (from 27.5 to 22.9%) but in absolute real terms (by a cumulative 5% over three years) and the deficit turned into a surplus within three years.

The trilogy was only intended to serve a medium-term adjustment purpose rather than act as a permanent or indefinite discipline and in that sense did not fit the strict definition of a fiscal rule. In the event, the early 1990s recession sent outlays up sharply again, the budget went back into even larger deficits than before the adjustment, and the trilogy was not heard of again. In the 1993 budget, the Keating government pledged only to peg the deficit back to 1% of GDP by 1996-97.

- 1996–2019: Discipline followed by drift

By 1995-96 the deficit was still running at 2% of GDP and debt had risen sharply. The Howard government was elected in 1996 on a platform of strong fiscal discipline. Over time, the key planks were articulated as:

- A legislated Charter of Budget Honesty (CBH);

- Returning the budget to underlying surplus in that term of government, and maintaining a balanced budget on average over the economic cycle;

- The tax to GDP ratio not to exceed its 1996-97 level of 22.4%; and

- Outlays and net debt to GDP to be reduced significantly until satisfactory levels were achieved.

These elements or variations of them remained throughout and beyond the Howard government but were challenged by the global financial crisis of 2008-09 and then even more so by the Covid-19 pandemic. They became the closest thing Australia has had to a set of long-term fiscal rules but were sometimes honoured in the breach or adjusted when convenient. For example:

- With the long run of surpluses in the ten years preceding the global financial crisis and the elimination of net debt, over-confidence set in and the balanced budget rule morphed into a surplus rule, but then entrenched deficits returned during and after the crisis. Looking at the 23 years to 2018-19 as a whole, the budget averaged an underlying deficit of about 0.6% of GDP — not balance let alone surplus – despite there being only one major cyclical setback (technically not even a recession) in that long period.

- The tax to GDP ratio has crept up over time despite caps, exceeding the original 1996-97 cap of 22.4% of GDP. However, interpretation is obscured by structural changes in the tax system, particularly introduction of the GST in 2000 which effectively shifted some taxation from the states to the Commonwealth. By 2007-08 the actual ratio was 23.7% including GST, which became the Rudd government’s new cap, subsequently to be reset by the Coalition government in 2018 to 23.9%, being the average of the Howard government years from the introduction of the GST in 2000-01 to 2007-08. The 2018 cap has not since been reached.[3]

- Expenditure constraints have been adopted at times in the form of speed limits on real growth rather than caps on ratios to GDP. However, the speed limits have been short-lived and more often than not exceeded. For some years there was also a rule requiring any new spending to be offset by savings, but this never stuck.

- The CBH does not specify fiscal rules. As described above, it mandates a framework and principles for fiscal transparency and responsibility, but a former Treasury Secretary has recently charged that even the principles are no longer being honoured.[4]

The strongest set of rules was that adopted by the Abbott government in its 2014 budget. These included an average surplus over the cycle, a falling expenditure to GDP ratio, falling debt, all new spending to be offset by savings, and all favourable revisions to spending and revenue to be ‘banked’, meaning they would be allowed to improve the budget bottom line. However, the 2014 budget failed to meet its objectives and the budget remained in deficit for another four years.

The one constant over the period from 1996 was the rule that the budget should be balanced or in surplus on average over the economic cycle, although what this meant in practical and monitorable terms was never spelt out. The long period of surpluses up to 2007-08 helped embed fiscal discipline as an economic policy norm and strengthened fiscal credibility. However, this happened with tax revenue outpacing the economy and government expenditure growing strongly. When the rules were tested under more difficult economic and political conditions after 2007-08, they did not prevent the budget from slipping into substantial deficits that persisted long after any case for fiscal stimulus had passed.

- The pandemic as the final blow to fiscal rules

The broad rules-based framework as described above, though imperfect, struggled on after the global financial crisis and by 2018-19 at least the underlying deficit had been eliminated with tax receipts running below the cap at 23% of GDP. However, the pandemic quickly put paid to any semblance of fiscal discipline and the rules were abandoned.

With the pandemic fading in 2022 the Morrison government declared a return to fiscal normalcy, bringing back the notion of a balanced budget on average over the economic cycle, keeping the 23.9% tax cap, ‘controlling’ expenditure growth (unquantified) and adopting the unambitious goal of stabilising and then gradually lowering the debt to GDP ratio. However, the government’s last budget, in March 2022, could only offer four years of substantial deficits ahead.

When the new Labor government handed down its first budget in October 2022, both the balanced budget rule and the tax cap were dropped and the key metrics of its fiscal strategy became vague notions such as “reducing gross debt as a share of the economy over time” and “limiting growth in spending” (unquantified), but only until gross debt as a share of GDP has started the said downwards trajectory.

The government has also made ‘banking’ (that is, not spending) a majority of any upward revisions of tax revenue a key measure of its fiscal discipline, but the revisions were so large that this was very easy to deliver even with spending increasing rapidly at the same time. More recently, as the upward revisions have faded, the government has not delivered.[5]

This is a description of fiscal strategy as it stands in 2025. There cannot be said to be any fiscal rules in any meaningful sense of the term. The CBH remains on the statute books and it is being complied with only in a mechanical sense that each budget contains a fiscal strategy statement. As noted above, a former Treasury Secretary has argued that every government since the Rudd government has breached the principles of the CBH.[6] The IMF, in its last review of the Australian economy, was lukewarm in its assessment of the current fiscal strategy and advocated clearer fiscal anchors.[7]

Against that, the government argues that a substantial budget correction has been achieved without quantitative fiscal rules. However, the correction was accidental and temporary — due to extraordinary favourable revisions to revenue — leaving a fiscal outlook in need of further action to rein in growth of spending and eliminate expected budget deficits.

This brief review of fiscal rules in Australia traces changes in political attitudes to fiscal restraint and discipline. Attitudes were favourable to discipline for much of the period up to the pandemic, but fiscal rules were a reflection and an expression of the prevailing political attitudes rather than the driving force. However, the rules helped achieve more disciplined outcomes at times when ministers chose to emphasise them in policy deliberation and in public debate.

Australia’s fiscal institutions

Fiscal rules need appropriate institutions to support them through design, articulation, implementation, monitoring and enforcement. At the national level, Australia’s public fiscal institutions are essentially the Departments of Treasury and Finance and the Parliamentary Budget Office. The Australian National Audit Office could also be said to have a relevant role, but its remit is narrower and mostly not directly relevant to fiscal policy.

Treasury and Finance are key fiscal institutions but as departments of state they serve the executive government rather than being independent of it. They advise the government on fiscal strategy and have a role in explaining the strategies as determined by the government, but monitoring and enforcement is best carried out by an independent institution.

The Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) is independent of the executive government. It is a parliamentary department that supports the parliament (as distinct from the executive government) and has operational independence within the restrictions of its legislated charter. The PBO was created in 2012 out of the conditions some independent House members advocated in return for their support of a minority Labor government after the 2010 election.

In its own words, “the purpose of the PBO is to inform parliament by providing costings of policy proposals and analysis of the budget, and to enrich Australia’s democracy through independent budget and fiscal analysis.” As well as serving the parliament, the PBO aims to “enhance public understanding of budget and fiscal policy settings.”[8]

The PBO’s charter denies it any part in budget preparation, developing its own budget and forward estimates, or evaluating the government’s fiscal strategy and performance. This, on some assessments, makes it weaker than comparable institutions in other countries and less well suited as an institution to reinforce fiscal rules. However, the PBO is free to issue self-initiated analytical reports on fiscal policy topics of its choosing and has a track record of doing so and of drawing attention to risks to budget sustainability and the achievement of stated government fiscal objectives. One of the PBO’s flagship products is its ‘Beyond the Budget’ analysis of the longer term fiscal outlook in which it develops its own long-term projections beyond the four years of budget and forward estimates, based on stated government policies.

International experience

There is a large literature on international practice and effectiveness in the use of fiscal rules and independent institutions to reinforce application and compliance with rules. Much of this research has been undertaken by the IMF and the OECD, international organisations that have been strong advocates of fiscal rules and independent fiscal councils.

The IMF reports that the use of fiscal rules has increased markedly since 2000 and that at the end of 2024 more than 120 countries had at least one fiscal rule covering the central or national government, although about 20 of these only had supra-national rules (such as those of the European Union).[9] More than 50 countries had a fiscal council, which is defined as a public institution independent of political government set up for the purposes of providing or assessing budget estimates and forecasts, monitoring fiscal rules, making relevant policy proposals and participating in public debate on fiscal issues.

Both the IMF and the OECD have found through empirical research that fiscal rules have promoted stronger fiscal discipline and credibility, but this finding is heavily qualified. Where fiscal rules have been successful they have included clear fiscal anchors, robust correction mechanisms for when limits have been breached and the flexibility to respond to shocks, and have been supported by strong independent fiscal councils. In many instances these conditions are lacking. It is not surprising, then, that the IMF found recently that “compliance (with rules) remains uneven, with widespread and persistent deviations from deficit and debt rule limits”.[10]

Issues in the formulation of fiscal rules

There is a long list of technicalities to consider in formulating fiscal rules such as:

- If the fiscal starting point is deficient, there may need to be one set of rules for an adjustment period and another set to apply in the longer term if and when the adjustment to a satisfactory fiscal position has been achieved.

- Independently of policy measures, expenditure, revenue and the budget balance are subject to the economic cycle and rules need to take this cyclicality into account.

- The federal government’s fiscal statements have always emphasised cash payments, receipts and the deficit or surplus, but there is an alternative set of accrual accounts (like those of a business) that by many criteria are better and more comprehensive.

- Related to the previous point, there are at least five definitions of the budget balance to choose from:

- the ‘underlying cash’ result that governments have emphasised since 1996;

- the ‘headline’ cash result which brings in financial investment outlays and receipts that are excluded from ‘underlying’ cash;

- the primary result, which excludes debt interest expense;

- the net operating balance, which is an accrual concept that excludes capital expenditure but includes depreciation expense; and

- the fiscal balance, another accrual concept that includes gross capital expenditure rather than depreciation.

- Should a balanced or surplus budget be targeted for operating expenses and revenues only, leaving net capital expenditure to be debt-financed and, if so, subject to what restrictions?

- Rules are sometimes expressed as expenditure and revenue as percentages of GDP, but such percentages are very difficult to target and can vary over a wide range due to influences on both the numerator and the denominator that do not necessarily come from government policy decisions.

- The rules could apply ex ante (to budget and forward estimates) or ex post (to actual outcomes). If they apply only ex ante, and outcomes do not comply with the rules, then the government should at least be required to explain the failures.

- If outcomes do not comply with the rules, there may need to be correction mechanisms to bring the budget back on track or perhaps go further to require additional adjustments to compensate for the outcome failures. The correction mechanisms need to take into account the reasons for the failures.

- There need to be escape clauses allowing the rules to be suspended for exceptional circumstances such as exogenous financial crises, wars and prolonged recessions. However, if escape clauses are too broad and flexible they risk undermining the robustness and credibility of the rules.

- Even if rules are set in legislation they are unlikely to be enforceable in any court. In any case, the parliament cannot be prevented from changing the rules at any time. Accountability of the government to the parliament and the public is a minimum, and this can be supported by institutional arrangements that make breaches of the rules as transparent as possible and raise their profile. Beyond this, it has sometimes been suggested that a financial penalty be imposed on parliamentarians for breaches, but this would require an outside body to make rulings and administer the penalties.[11]

New fiscal rules for Australia

While rules are needed for the long-term, there also needs to be a reduction in projected deficits over the next few years. The question is how quickly this should happen. This will depend on economic conditions (real growth, employment growth, inflation, commodity prices), but given current and officially forecast conditions, it could and should happen over a period of a few years – call this the consolidation period. This calls for a tighter set of rules for the consolidation period than for the longer term.

The alternative is to build the adjustment into the long-term rules, but this risks unforeseen events over a long period intervening to prevent the adjustment from ever happening and the current structural fiscal weaknesses being locked in for the long-term. There have been adjustment periods of three to four years in the past — in the late 1970s, the mid-1980s, the late 1990s and (unsuccessfully) after the GFC.

There was also a post-pandemic adjustment that saw the budget swing sharply from a large deficit to two years of surplus in 2022-23 and 2023-24 and gross debt decline from 39% of GDP to 34%. However, this adjustment drew on a very large increase in revenue and left structural weaknesses in place only to reappear as revenue conditions normalised. The key feature has been strong expenditure growth which has kept spending relative to GDP well above past norms.

A concentrated, medium-term drive to balance the budget on a sustainable basis over the next three or four years would be consistent with the past pattern. This approach is reflected in the fiscal rules proposed below in Table 1.

The CBH should remain in place but amended to incorporate the fiscal rules so as to give them legislative standing. This, admittedly, would be largely symbolic rather than make compliance enforceable, but it would raise the stakes for non-compliance and focus the political spotlight on any attempt to change the rules.

Table 1: Fiscal Rules for Consolidation and the Long-Term

Discussion

- Balanced budget

As discussed above, for many years before the pandemic there was a rule specifying a balanced or surplus budget on average over the economic cycle. This was always cast in terms of the ‘underlying’ budget balance, which excludes financial investment outflows such as the government’s equity investments in public enterprises and inflows such as from privatisations.

The balanced budget rule needs to be restored in order to contain public debt and lower it over time, at least relative to GDP. However, there is a question as to whether it should apply to the underlying or headline balance, the latter including financial investment flows. Applying it to the headline balance would be a break from the past, but there are strong arguments for doing so in light of the increased resort in recent years to outflows classified as ‘financial investments’ and the fact that it is the headline balance that determines the government’s borrowing requirement.[12]

The concept of the underlying balance was adopted in the 1990s when the government was receiving substantial proceeds from privatisation of public business enterprises such as Telstra. As such proceeds are one-off, including them as budget receipts gave a distorted picture of the ongoing health of the budget. Omitting them from the underlying budget made the budget balance look worse, but it was a more realistic picture.

By contrast, there are now no privatisation proceeds but substantial net outflows supposedly for investment purposes, and leaving these outflows out of the underlying budget is making it look better and less meaningful as an indicator of the ongoing budget position because these net outflows have become routine, not one-off, and the financial outlays rarely achieve a commercial return and more often incur losses.

For these reasons, the rule should be that the headline budget result will strengthen (that is, the deficit will shrink) during the consolidation period to a balanced position over three or four years provided there are no recessions or adverse shocks in that period.

The long-term rule should be that the headline budget result will be balanced on average over the economic cycle, but with surpluses of at least 1% of GDP when the economy is growing at or above trend.

There is a risk that an underlying budget deficit could be masked by one-off asset sales or privatisation proceeds. Consideration should therefore be given to excluding such receipts from the calculation of the budget balance for purposes of compliance with this rule.

- Expenditure restraint

A balanced budget rule alone is sufficient to control public debt, but it says nothing about how it is to be achieved. It leaves a government free to ramp up both expenditure and taxation together while still balancing the budget. Not only would this be economically damaging, but experience both in Australia and other countries also suggests that a lack of expenditure discipline will before long lead to sustained deficits and a build-up of debt. For this reason, there is a strong case for rules for expenditure and tax restraint.

The most important contribution that rules can make to improve the fiscal outlook without tax increases is to curb the growth of government spending from its current elevated pace. If this is achieved everything else will fall into place more easily. The 2025-26 budget estimated budget cash payments to be 27% of GDP this fiscal year, easing back to 26.4% by 2028-29 subject to many risks including pressure for higher defence spending and failure to rein in the cost of the NDIS as planned. This compares with a pre-pandemic 5-year average of 25% and a pre-GFC average of about 24%.

Bearing in mind the difficulty in targeting spending as a percentage of GDP, the rule should be set in terms of a nominal growth rate, which is the aggregate over which governments have most (but still not full) control.

For the consolidation period the growth rate should be equal to the mid-point of the Reserve Bank’s inflation target of 2.5% — meaning that real spending would be flat — until the budget is balanced. If inflation is higher, real spending would fall, and if lower, real spending would increase, which would be appropriate counter-cyclical variations. At current estimates, this degree of restraint would need to continue for three years to reach approximate budget balance in underlying terms and payments, which as a proportion of GDP would be close to 25%.

The consolidation outcome for the headline cash balance would depend on what are labelled in the budget ‘net cash flows from investments in financial assets for policy purposes’ — or ‘net financial investments’ for short. If these occur as currently estimated — averaging 0.7% of GDP out to 2028-29 — the consolidation period for underlying payments would need to extend further to accommodate these ‘net cash investments’ and reach a balanced budget in headline terms.

Holding nominal payments growth to 2.5% for three years would not be easy — but fiscal consolidation is always difficult. It would mean freezing payments in real terms and reducing them in real per capita terms by about 4% over three years. This is not without precedent — the mid-1980s consolidation went much further, cutting real payments by a cumulative 5% and real per capita payments by 10%. However, it is clear that reductions in administrative expenses would not be sufficient. Cuts to programs (or slower growth rates), including ‘sacred cows’, would be needed. For example, growth in NDIS costs would need to be reined in much further than the government’s current 8% growth target.[13]

For the longer term, the spending rule should be a nominal growth rate of 2.5% (the inflation target mid-point) plus trend population growth plus trend productivity growth. Given current population and productivity trend assumptions, this would translate to nominal growth of about 4.5 to 5%. Growth in real spending per capita would be governed by productivity growth, which is a measure of what the economy can afford.

Net financial investments in their scale and nature have become a serious risk to budget credibility and need to be included within the scope of fiscal rules. These investments add to the government’s borrowing requirement. It is doubtful whether many of the outlays made under this heading qualify as ‘investments’ in the sense that they will generate a satisfactory return and be capable of being recouped or sold off at some point. It is more likely that some of these so-called investments are expenditures by another name.

To guard against abuses, all proposed investments should require certification by an independent accounting authority — perhaps the National Audit Office — that they qualify as investments, otherwise they must be classified as regular expenditure.

- Tax restraint

The purpose of a tax cap is to prevent the overall tax burden from creeping up over time through explicit tax increases or bracket creep. Such a cap is essentially a backstop in the event expenditure restraint is insufficient to balance the budget or a government seeks tax increases to achieve a surplus. The Coalition government up to 2022 applied a tax receipts cap of 23.9% of GDP. This was discarded by the Labor government, but outcomes up to 2024-25 have remained below 23.9% — the actual figure for each of the last two years being 23.7%.

The problem with a tax cap expressed as a percentage of GDP — especially one as precise as 23.9% — is that the ratio is highly variable and impossible to target with any accuracy. As with the expenditure cap, the tax cap should be expressed as a growth rate in nominal tax receipts, but in this case a trend growth rate recognising that actual growth in any particular year may be above or below the trend depending on economic conditions at the time.

For the consolidation period, tax receipts should be capped at the current forward estimates to 2028-29, subject to an escape clause that receipts may be higher if economic conditions prove more favourable to revenue growth — in which case all of the excess would flow to accelerating the return to a balanced budget. The tax receipts estimates in the 2025-26 budget implied an average growth rate of 4.8% to 2028-29.

Moving from consolidation to long-term rules, the tax receipts trend growth rule should be calibrated to the expenditure growth rule, which is likely to be 4.5–5% as shown in Table 1. This would be below the past long-term average of 5.8% since the start of the GST in 2000-01. It would be lower reflecting lower population and productivity growth. However, as with the consolidation rule, under the long-term rule actual tax receipts in any year may be above or below trend depending on economic conditions, generating a surplus at times of buoyancy and a deficit at times of slack.

It should be noted that total revenue is larger than tax revenue as there are non-tax receipts of around 2% of GDP compared with tax receipts projected to be 23.4% in 2028-29.

It should also be noted that the tax rule and the expenditure rule are only intended as ceilings and it would be open to any government to target smaller government with lower levels of tax and expenditure, provided they are consistent with a balanced budget.

- Debt

Adherence to the rules for spending, taxing and the budget balance would be sufficient to constrain and reduce debt and the interest bill over time. In an accounting sense, a separate debt rule becomes redundant. An alternative approach is to specify only a debt rule, but this would merely set the end-goal without any actionable rules for how to achieve it. Moreover, any figure for a prudent limit to debt is essentially arbitrary given the uncertainties about what level of debt burden would trigger a disruptive market reaction.

If it is still thought desirable to have a debt rule for presentational purposes, it should state that during the consolidation period the ratio of debt to GDP should clearly peak and begin to decline which would be likely given past consolidation episodes to see federal gross debt at face value shrink from where it is now — around 35% of GDP — by at least 5 percentage points in three or four years. The decline should accelerate once the long-term rules come into force, and the absolute dollar amount of debt should also decline as long as the economy is growing at or above trend.

Any target should be gross debt at face value, not net debt at market value, which can be distorted by fluctuations in interest rates and is subject to uncertainties about the liquidity of the financial assets included in the net debt calculation.[14]

Institutional changes: monitoring, reporting and enforcement

Australia’s current fiscal institutional arrangements and their shortcomings are discussed above. One key change is that assessment of compliance with fiscal rules and reporting should be undertaken by a body independent of executive government.

The obvious candidate is the PBO, which should also be tasked with proposing policy corrections in the event of non-compliance, although formulation of the rules should remain a government responsibility. To the extent the PBO’s current charter does not allow such functions, the enabling legislation should be amended to broaden its role.

Enforcement is the most difficult aspect. The term should not be taken literally, as it is impossible to find any example in the world of a politician or other public office-holder being penalised for a breach of fiscal rules. In the European Union a member country can be fined up to 0.05% of GDP for a breach of the EU fiscal rules, but this has never happened even though there have been many breaches. In Australia no court is likely to say that fiscal rules are enforceable even if they are set in legislation. Enforcement in practice is likely to mean maximum exposure of breaches by an independent body and pre-determined steps the government is required to take to explain breaches and propose corrective measures.

Conclusion

Economic management in Australia currently lacks the guardrails provided by quantified fiscal rules — and it is drifting into the increasingly risky terrain of excessive and sustained deficits and rising debt based on historically high levels of government spending and taxation. The risks take the shape of macroeconomic instability and further undermining of the foundations for productivity growth. Fiscal rules do not work magic but they can help restore and sustain budget discipline and entrench credibility provided the political will exists to follow the rules.

Past practice both internationally and in Australia has seen rules for one or more of the budget balance, expenditure, revenue and debt, with tighter control of expenditure being pivotal. Rules should be designed for long-term application, but the current fiscal position does not provide solid foundations for long-term rules to be applied. Rather, the rules need to distinguish between a short-term consolidation period and longer-term equilibrium characterised by balanced or surplus budgets and lower government expenditure.

This paper has proposed a set of rules to satisfy these criteria, with nominal annual expenditure growth capped at 2.5% until sustainable balance is reached and then capped at that rate plus trend population and productivity growth for the longer term. This would allow expenditure to grow in real terms to the extent of productivity growth. The paper also proposes consistent rules for tax revenue and the budget balance. The rules should be cast in legislation by way of amendment of the Charter of Budget Honesty.

Changes to fiscal institutions are suggested for effective, independent monitoring and reporting on the application of these fiscal rules.

Attachment: Fiscal Strategy Statements at Selected Budgets[15]

Endnotes

[1] David Gruen and Amanda Sayegh, ‘The Evolution of Fiscal Policy in Australia’, Treasury Working Paper 2005-04, November 2005 (treasury.gov.au/publication/2005-04-the-evolution-of-fiscal-policy-in-australia)

[2] Gruen and Sayegh, as above.

[3] The tax cap has always been based on cash tax receipts. The alternative measure is accrual tax revenue, which was above 24% of GDP in 2023-24 and 2024-25 compared with 23.7 percent for cash receipts in both years.

[4] ‘Punishing tax system breaks budget law, mugs the young: Henry’, Australian Financial Review, 20 February 2025.

[5] ‘Labor breached its savings rule three times’, Australian Financial Review, October 10, 2025.

[6] ‘Punishing tax system breaks budget law, mugs the young:Henry’, as above.

[7] Australia: 2022 Article IV Consultation, Staff Report, February 1, 2023 (International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC)

[8] Parliamentary Budget Office, pbo.gov.au/about-the-pbo; and Annual Report 2024-25, October 3, 2025

[9] Fiscal Rules and Fiscal Councils: Recent Trends and Revisions since the Pandemic, IMF Working Paper No. 2025/198, October 3, 2025 (International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC)

[10] As above.

[11] Stephen Kirchner, Strengthening Australia’s Fiscal Institutions, CIS T30.06, December 2013 (Centre for Independent Studies, Sydney)

[12] Parliamentary Budget Office, ‘2025-26 Medium-term Budget Outlook: Beyond the Budget’, September 2025: Evolving Use of Alternative Financing Arrangements, pp 7-9.

[13] The Minister for Health has foreshadowed a revised “medium to long term” growth target of 5 to 6%, but he put no time-frame on it and no Scheme changes have been announced to achieve it (Speech to National Press Club, 20 August 2025).

[14] As interest rates fall/rise, the market value of outstanding debt rises/falls.

[15] Source: Commonwealth budget papers for these years, Budget Paper No. 1, Budget Strategy and Outlook.