Executive summary

Several well-known bodies, from the Productivity Commission to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, the Minderoo Foundation and even a South Australian Royal Commission, have examined Australia’s childcare markets. I aim in this report, which I drafted before reading the reports of any of the above-mentioned eminent bodies, to provide a balanced view of the present state of the Australian childcare system and some recommendations for reform.

Childcare as a composite good, rather than early education alone, is my main focus, meaning that detailed questions about how best to structure educational activities for children in care are considered out of scope — although such questions will be considered in future CIS reports. Rather, I aim to take an economist’s lens to the present state of Australia’s childcare markets, and to the problem of why and how government should optimally intervene in these markets, bearing in mind the strategic economic objectives of childcare for individuals, for families, and for Australia as a whole.

The thematic structure of the report and its main conclusions are summarised below.

1: Charting the history and present status of childcare markets and the Australian government’s involvement in them. While initially subsidised via supply-side measures, Australia’s childcare sector features a mix of public and private providers of long daycare and family daycare, and is now supported by demand-side subsidies. Increasing these subsidies has not worked to reduce fees. Accessibility is highly regionally variable.

2: Considering how one might try to calculate a return on investment for government spending on childcare. I argue that a precise ROI calculation is infeasible, but that some level of government involvement in the sector is supported by the economic rationale that investments in childcare carry public benefits not fully recouped by individuals and families, especially in the domain of improving the quality of care in the early years of disadvantaged children whose alternative care options are poor, and also potentially in the domains of efficiency and productivity.

3: Examining the regulatory context and quality assurance system for childcare. These systems are by turns stifling and inadequate (see the online appendix to this report), focusing on measures unrelated to or incapable of capturing the majority of what goes into creating child wellbeing.

4: Looking abroad and in Australia at what has been experienced and what is known about different approaches to organising childcare. Some peer nations use supply-side subsidy systems and are moving more in that direction, while others use demand-side subsidy systems. What is most important for children is not well measured by ‘structural’ quality metrics only. There is a need here to include the domain of ‘process quality’, such as the quality of the relationship between a carer and the child in her care. Quality problems in Australia’s childcare system have been noticed often, including very recently.

In this report, I consider from several angles how one might justify government intervention and how, if government does intervene, one might quantify the value of that intervention to children and Australia as a whole. I find that the Australian government’s childcare policies are likely to be significantly constricting market forces. While well-intentioned, the heavy government interference in the dimensions of educator qualifications and quality regulation are evidently not improving the school readiness of our children. It also is almost surely dissuading would-be educators from entering the market and crowding the time of existing educators who would be using that time to care for children if they did not have such a significant regulatory burden. I suggest that modern technological solutions make it possible to radically decentralise quality management, and that the qualification of prospective childcare providers should be assessed via a procedure more similar to the procedures presently used to assess the qualification of workers for jobs in other sectors of the economy.

Recognising that parents have a strong interest in ensuring their children are well cared for, I propose that we elevate their opinions. Rather than emphasising how little they can know about the quality of care, we should use the information they have good reason to observe locally in order to more effectively gauge, and more widely publicise, the quality of care provided at different centres. I also propose, based on my review, that the present demand-side childcare subsidy system is not delivering the desired results.

The recommendations I arrive at are as follows, and are more fully fleshed out in the final pages of this report:

TIER ONE (recommendations)

- Radically modify the process for qualifying new educators.

- Decentralise the childcare quality verification process, drawing on modern technological solutions unavailable only a few years ago.

- Strongly recommend family daycare rather than institutionalised care for infants and toddlers, when not cared for by their own families.

TIER TWO (suggestions)

- Investigate other approaches to subsidising care, while taking on board lessons from imperfect supply-side approaches overseas and the failings of the current system. Designers should prioritise models that allow consumers greater choice, rather than a one-size-fits-all approach, and that allocate government support to families most in need of it.

- When establishing more government-run childcare centres in areas of need, ensure that family daycare is a significant part of the mix.

KEY RISK in trying to implement this advice:

- Entrenched interests that benefit from the existing regulatory framework will resist deregulation and push for even more stringent regulatory oversight, more unnecessary educator qualifications and more bureaucracy, all in the name of ‘quality improvement’.

I recognise that these recommendations, taken together, constitute a shift in the way childcare is managed in Australia. Implementing or even considering such significant changes will naturally encounter political and bureaucratic challenges, on top of the above-mentioned resistance from entrenched interests. Transitional plans will be required to facilitate the change in thinking and policymaking that these recommendations invite.

I hope that whether you are a parent, a policymaker, a childcare provider, or a prospective parent or childcare provider, you find this report of value.

1. Why the design of childcare and early learning systems is a core economic policy area

1.0 Introduction and statement of intent

How the daily lives of society’s youngest members are organised carries profound economic consequences.

First, it influences the extent to which their parents, and particularly their mothers, contribute their labour to productive work or study beyond child-rearing.

Second, it affects the size and characteristics of the childcare sector: the number of jobs available, the working conditions in these jobs, the selection of people into these jobs, and the resources that are combined with paid labour on a scale and/or in settings different from the child-rearing services typically provided gratis within the family home.

Third, it helps mould the make-up and character of neighbourhoods, both at a high level through potential effects on the fertility decisions of families, and at a neighbourhood level whereby there are larger or smaller groups of young children accompanied by professional carers, parents, or other adults, using public goods like libraries, parks and playgrounds that will be associated with varying degrees of intergenerational social mixing.

Fourth, it carries health implications, channeled through regulations in the professional childcare sector (like requirements that participating children be vaccinated, or that meals be of some minimal nutritional standard) and mechanically through changes in how health-relevant things like hygiene, affection, beliefs and habits are transmitted from person to person in unpaid care settings like families versus large groups of children in paid daytime care.

Fifth, what children experience during their earliest years carries profound consequences for what sort of adults they will become — courageous, skilled, compassionate, confident, productive, hopeful, or otherwise — and thereby has huge implications for the future economic and social potential of our country.

Of these, the phenomena most recognised and studied in the economic and policy literatures are:

(1) the liberation of parenting labour for other purposes (with downstream effects like career fulfilment or higher retirement savings for mothers) when it is replaced by paid or unpaid non-parental care[1]; and

(2) the effects on the children themselves and/or on future productivity that arise from the experiences young children have today.

The primary objective of this report is to assess the organisation of the daily lives of children aged 0 to 4 in Australia, and to determine whether present policy settings relevant to parental choices are likely to be optimal. ‘Optimality’ is conceived here as achieving the most ‘social welfare’ for Australia today and into the next generation, via mechanisms such as:

- encouraging at least replacement-rate fertility levels while optimising (not necessarily maximising) female labour market participation and hours worked;[2]

- achieving a high quality of match between employees and jobs, and high job satisfaction, in and outside of the care sector; and

- achieving robust support for children’s healthy development.

I will particularly focus on whether the market for paid care is free, informed, and functioning in a healthy fashion, what market failures are anticipated or evident that may justify or be caused by government intervention, and what factors are driving parents’ choices about what their children experience. I consider the different policy settings across Australian states and territories, as well as other countries’ policies and what the academic literature has found about the relationship between the nature of care and economic outcomes of interest, using Australian and other Western data.

By the end of this report, my hope is that the reader has a better foundation from which to consider the potential effects of different care options and policy settings on:

- childcare quality;

- accessibility and affordability of childcare;

- paid labour supply;

- the extent to which satisfying jobs and community cohesion are created through paid or unpaid interactions with young children; and

- the creation of a productive, happier, healthier future workforce.

Most importantly, I aim to convey a holistic picture of how Australia’s policy settings shape what happens to its young children and those who care for them, and to survey the alternatives that are possible and may be better, based on what we have seen in Australia’s past and elsewhere in the world. The report closes with several recommendations for policymakers wishing to enact reform that I believe will better serve Australia’s collective interests.

1.1 Terminology and framing

The terms ‘childcare’ and ‘early learning’ are often used in the policy and academic literatures in different contexts, although in a practical sense they often refer to the same phenomenon. The first term, ‘childcare’, is typically used when implying that a young child’s experience is considered primarily relevant to whether he is being looked after adequately so that others (usually his parents) may engage in alternative activities.

By contrast, the phrase ‘early learning’ is typically used to emphasise that the experiences of young children present opportunities to invest in those children’s human capital formation. In this report, for brevity, I will use the term ‘childcare’ to denote both ‘childcare’ and ’early learning’, while recognising that every one of the experiences that a young child has can be profoundly formative for him or her.

In the case of any area of the economy in which government intervenes, it is prudent to ask what justifies that intervention. One may argue that education — even that of very young children — is a ‘credence good’[3] (or ‘experience good’) whose quality is not directly apparent to parents, in which case an aim of government intervention in this sector would be to ensure a minimum level of quality is provided by suppliers, as is aimed for in other sectors, for example via food quality standards. Another justification may be that high-quality childcare is a public good, carrying social benefits beyond the private benefits that the child and his parents receive, and hence in expectation will be under-provided by the free market.

2. Policy, law, regulation and structure of the childcare industry

2.1 Background

Childcare in Australia is segmented into four categories, of which the first two come within the scope of this report since they are relevant for children of younger than school age, meaning typically 0-5 years old:

- Centre-based daycare. Sometimes referred to as ‘long daycare’ centres, care for groups of children eight or more hours a day for five days a week. The children are usually aged six weeks to school age and the groups can be large, ranging from about 10 to more than 80 children. The biggest player in this sector in Australia is Goodstart Early Learning, which operates around 650 centres, out of a total of about 9200. Goodstart is a partnership of four non-profits that took over the remains of ABC Learning, a private-sector operator that collapsed in 2008.

- Family daycare. Family daycare is a type of daycare in which a parent or other approved adult cares for a maximum legal number of seven children in her own home. Hours of operation can be similar to long daycare centres but may be more flexible and also cater to children on school holidays.

- Out of school hours care (OSHC). Centres providing OSHC cater for children physically present at school outside of normal school hours and on holidays. They are often attached to or near primary schools.

- In-home care. In some cases, paid care is provided by an individual in the home of the child. Governmental support for this type of arrangement is restricted to situations where the child is unable to access care outside the home.

In this chapter, I will first review the history of public childcare support in Australia, and then examine the present state of the sector on both the demand and supply sides.

2.1.1 How did the Australian government get into the business of childcare?

The Australian government entered the childcare business with the Child Care Act of 1972, the principal result of which was public investment in the provision of non-profit childcare. This took the form of funding for childcare facilities run by local governments, community groups and other non-profits. Funding was provided to cover the costs of qualified staff salaries and for the start-up costs of building new centres or repurposing existing facilities.

Significant changes to the way childcare was supported by the federal government were introduced in 1986 when the staff salary subsidy was replaced by a per-capita subsidy for each childcare place in a centre. The change resulted in centres losing about 50% of their operational funding, with an adverse knock-on effect to fees.[4] At the same time, fee relief was extended for low-income families. This represented a clear pivot in government support for the industry from subsidising the supply side to subsidising the user.

Then, in 1990, the government extended its fee relief subsidy to families using private-sector childcare, and introduced other measures to encourage private operators to enter the sector to meet demand. These reforms initiated an influx of private service providers, responding to the incentive to charge the fees that demand-side subsidies permitted.[5] By 2024, approximately 70% of all centre-based daycare services were operated by private for-profit entities,[6] with the rest being run by community-based non-profits, state/local governments, and schools.

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) inquiry into the childcare sector published in 2023[7] found that “[f]or-profit providers of centre-based daycare continue to charge higher fees and increased fees, on average, by more than not-for-profit providers”, over both the short and medium run. This may be unsurprising given the cost structure of for-profit care provision is more challenging, as it includes such items as tax liabilities and full-cost venue hire, relative to the cost structure of not-for-profit care provision. At the same time, multiple sources in Australia and overseas indicate that the quality of care at for-profit centres tends to lag the quality of care at not-for-profit or public centres.[8]

Federal subsidies in one form or another for users of childcare increased steadily from the early 1990s onward. A major inflection point was the introduction of the Child Care Subsidy (CCS) in July 2018, which replaced the existing Child Care Benefit and Child Care Rebate. This subsidy is paid not to the family but to the childcare service which, in turn (in theory), lowers the fee faced by the family. Despite the subsidy, the ACCC estimated in its above-referenced 2023 inquiry that an Australian couple on average wages and two children spent 16% of net household income on childcare, well above the OECD average of 7%. (Seven per cent also happens to be the generally accepted international benchmark.[9])

Largely based on the temporal association between increased demand-side subsidies and increased user fees, governmental attempts to bring down out-of-pocket childcare costs via increasing demand-side subsidies have been seen, by and large, as failures.[10] Underscoring this perception, the above-referenced ACCC report states on page 2 that its “inquiry finds that historically when subsidies increase, out-of-pocket expenses decline initially but then tend to revert to higher levels. This is because subsequent fee increases erode some of the intended benefit for households over time”.

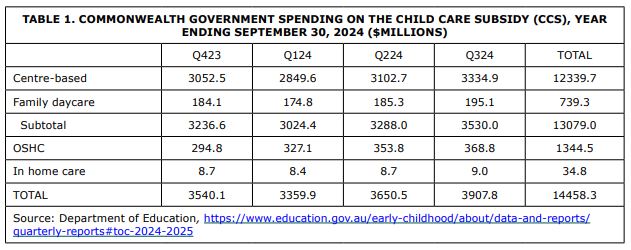

By the year ending September 2024, the cost of the CCS totalled more than $13 billion for centre-based and family daycare users alone. (An additional $1.4 billion was spent subsidising OSHC and in-home care.[11])

Childcare can be a profitable business if it is well managed. The biggest private-sector chain in Australia, G8 Education, has more than 400 centres under 22 brand names. It pulled in revenues of more than $1 billion in FY2024 with an EBIT margin (the ratio of earnings before interest and taxes to revenues) of 11% and an after-tax profit of $68 million.[12] However, the private childcare sector can also be plagued by incompetence and poor reporting practices, as in the case of ABC Learning which collapsed under a mountain of debt in 2008. It was subsequently taken over by a consortium of not-for-profits and the name was changed to Goodstart Early Learning, which, as noted earlier, still operates about 650 centres.

2.1.2 Apparent economic rationale

A report by the Economic Planning Advisory Commission (EPAC) in 1996 recognised both equity and efficiency reasons for government intervention in the childcare market. The equity argument was that lower-income families would be priced out of access in a purely market-driven system, thus denying them opportunities to participate in the workforce. Second, a series of efficiency arguments were made:

- Families might not be able to get the information they needed to make optimal decisions in the private market (a flavour of the ‘education is a credence good’ argument, related to asymmetric information);

- Children and the community benefit from the early childhood education and socialisation made possible by quality childcare (a public-goods-style argument);

- By permitting parents to re-enter the workforce more rapidly, public investment in education and training of those same parents suffers less depreciation (a pure efficiency argument, although one that invokes a more modest role for government intervention, to the extent that parents’ own private incentives are aligned with minimising this depreciation).

It is also possible for government intervention to confer direct fiscal benefits if the additional tax revenues and reduced welfare payments made possible by wider access to childcare more than offset the direct expenditure on childcare subsidies.[13]

From the conventional standpoint of evaluating the efficiency of government expenditure, one might desire to estimate a return on investment that expresses, in a way comparable to other government expenditure line items,[14] the net benefits of public investment in childcare. An ROI calculation would logically require estimates of additional tax receipts, reduced welfare payments, and the marginal public returns during the lifecycle of children who experience a care environment better than they would have experienced in the absence of government support for childcare. I consider the feasibility of generating an ROI estimate later in this report, and ultimately conclude that it is not feasible to come up with a reliable estimate for reasons for reasons I explain in Section 2.6 of this report.

2.2 Current government childcare policy

The policy approach of subsidising families for their use of paid childcare was most recently extended in new legislation passed by Parliament on 13 February 2025 — the Early Child Education and Care (Three Day Guarantee) Bill 2025 — which guarantees children a minimum three days per week (100 hours per fortnight for indigenous children) of subsidised daycare regardless of the work or study status of either parent, beginning 5 January 2026. It supersedes the Family Assistance Legislation Amendment, or ‘Cheaper Childcare Bill of 2022’, in particular by eliminating the so-called ‘activity test’. Under the new legislation a family receives 90% of out-of-pocket expenses, subsidised up to a family income of $83,280. This is reduced by 1% for every additional $5000 of family income, meaning that the subsidy does not reach zero until a family earns $533,280 per year. Families with more than one child under five years may be entitled to a higher subsidy.

In the most recent 12 months for which data are available, the CCS cost the Commonwealth government $14.5 billion, divided up by type of care as shown in Table 1. Just over 85% of the subsidy goes to centre-based care. Note that the Commonwealth government budgeted an additional $426.6 million for the Three-Day Guarantee in its 2025-2026 budget handed down on 25 March 2025. It also committed $3.5 billion over two years beginning 1 January 2025 to support a wage increase for childcare workers.[15]

On the supply side, the new legislation would commit $1 billion starting in July 2025 to a ‘Building Early Education Fund’ to build new daycare centres and expand existing ones in areas where intervention is needed, many of which will be in outer-suburbs or regional areas where there are so-called childcare ‘deserts’. Specifically, according to the Department of Education, the fund will “build and expand around 160 Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) centres in areas of need, including the outer-suburbs and regional Australia”.[16] Of course, politicians sometimes break promises, and there is no guarantee that this latest promise will not be abandoned — something that happened in 2007 when the Rudd government promised 260 new childcare centres but ended up building fewer than 40.[17]

The fund includes $530 million in capital grants to incentivise “quality not-for-profit ECEC providers and state and local governments to establish new services and increase the capacity of existing ECEC services. Grants will be targeted to priority and underserved markets, including regional locations and the outer-suburbs. The legislation indicates that “[w]here possible, services will be located on or near school sites”. In addition, $500 million will be invested by the government “in owning and leasing a portfolio of early childhood education and care centres to increase the supply of services, with $2.3 million over two years from 2024-25 to undertake a business case to inform final design”.

2.3 Regulation and quality control on the supply side

Regulation on the supply side is voluminous and is aimed at ensuring quality services and integrating education into the ‘child-minding’ function of daycare.

The National Quality Framework (NQF), effective January 1, 2012, is the overarching system by which childcare is regulated in Australia. While in name its intent was to promote quality in childcare, Jha (2014) notes in a prior CIS report that the NQF was introduced with no regard to the existing evidence base concerning how to promote quality in childcare.[18] In her words: “The National Quality Framework reforms are not supported by a strong evidence base and are likely to increase the cost of childcare for families and taxpayers more than has been estimated” (p. 23).

Sitting inside the NQF are the Education and Care Services National Law, Education and Care Services National Regulations, a set of quality standards (the National Quality Standard, NQS), and two learning frameworks, one for school-age children and a 72-page learning framework for children aged 0-5, entitled Belonging, Being and Becoming: The Early Years Framework For Australia.[19] The NQF is administered by state regulatory bodies that are housed within each state/territory’s Department of Education or equivalent, supported by an independent federal body called the Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority (ACECQA).

Supply-side regulation of childcare is supplemented with a top-down quality assurance system in which self-assessment of quality is coupled with site visits made by representatives of the regulatory authority. The first quality assessment, called a Quality Improvement Plan or QIP, is required to be completed within three months of a childcare provider’s grant of service approval. Subsequently, QIPs are submitted at a minimum annually, or when requested by the regulatory authority, which frequently occurs in response to complaints.

The regulatory and quality-assurance setting in which childcare providers and workers operate is so extensive and onerous that conveying its elements within the main text of this report would impede its flow. One indicator of the increasingly stifling nature of government regulations in this area is the growing fraction of childcare centres that have been granted a waiver, typically of one year’s duration (though potentially extendable), enabling them to continue to operate despite being in breach of some aspect of childcare regulations.[20] I have included details in an online appendix about the existing quality-assurance system, as well as the levels of training involved (which are not even required for foster carers who deal with vulnerable children).

Glossary of childcare roles and qualifications

Educator. This term is the one applied to the actual in-home caregiver who looks after the children in a family daycare situation or the caregiver in a daycare centre. Although most parents of preschool children would be as or more concerned about things like physical safety, emotional wellbeing and opportunities for socialisation and play, the term ‘educator’ emphasises the teaching side of childcare provision in Australia.

Family daycare service. A family daycare service is not, as one might imagine, delivered by the parent or other adult caregiver at the coalface in their home each day looking after children. Rather, it is a service that recruits, manages and advises the individual family daycare ‘educators’. An educator must be registered with a family daycare service in order to be an approved daycare provider and become eligible for the childcare subsidy. Family daycare services are operated by local governments, churches, and community groups. Family Day Care Australia is the national peak body for family daycare services and one of its roles is to connect prospective educators with family daycare services in their local areas.

Family daycare coordinator. A family daycare coordinator is a professional staff member within the family daycare service who oversees the educational programs and care provided by the educator. Coordinators assist educators in the design, planning, implementation and evaluation of their educational programs.

Early childhood teacher (ECT). An ECT is a person who holds a Bachelor’s degree in Early Childhood Education. These individuals are hired by childcare centres to assist educators with their education programs. There are strict rules surrounding the required accessibility to ECTs of each centre that are determined by the number of children in the centre.

Diploma in early childhood education and care. A favoured qualification for childcare educators. According to the government website, training.gov.au: “Educators at this level are responsible for designing and implementing curriculum that meets the requirements of an approved learning framework and for maintaining compliance in other areas of service operations. They use specialised knowledge and analyse and apply theoretical concepts to diverse work situations. They may have responsibility for supervision of volunteers or other educators”.[21] There are around 100 diploma-level qualifications approved by the federal regulatory body, the Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority (ACECQA), and listed on the ACECQA website.[22]

Certificate III-level qualification. This is a lesser qualification than a diploma. The other 50% of educators in a centre-based service who do not have a diploma or are not actively working towards one must either have a certificate III-level qualification or be working towards that. Family daycare educators must hold this qualification ― they cannot just be working toward it. There are 22 accredited programs currently approved by ACECQA and listed on the website that are certificate III-level. According to training.gov.au, the holder of a certificate III qualification will be able to “support children’s health, safety and wellbeing, drive children’s holistic learning experiences, [and] support children’s wellbeing and development in the context of an approved learning framework”.[23] For more on this, see the online appendix.

2.4 Demand and supply analysis

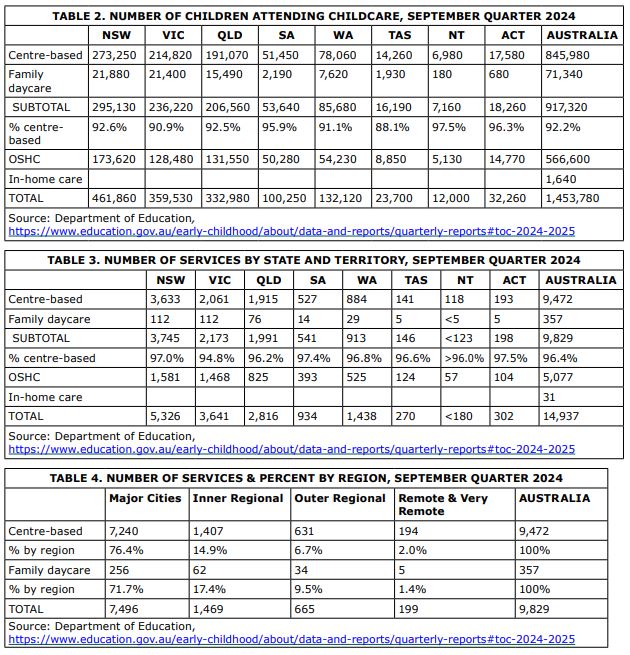

According to the Department of Education there were 917,320 children using either centre-based long daycare or family daycare as of September 2024. (A further 566,600 were using OSHC (outside school hours care), a separate category that is outside the scope of this report.) Productivity Commission data for the year ending June 30, 2024, indicates that attendance in a formal childcare setting peaked at age 3 with 68.6% of children participating. The percentages were similar but slightly lower for 2-year-olds and 4-year-olds (65.1% and 63.4%, respectively). However, after age 4 the percentage of children in formal childcare fell away sharply, to 43.9% for children aged 5, as they left childcare to go to preschool or school. At the youngest end of the continuum, only 11.1% of children under 1 year of age, and 47.9% of 1-year-olds, were participating in formal childcare.[24]

The overwhelming majority of places in centre-based and family daycare services (92.2%) are centre-based, ranging from 88.1% in Tasmania to more than 96% in the two territories (see Table 2). Across the entire country there are fewer than 360 family daycare services, and those that do exist are heavily concentrated in NSW, Victoria and Queensland (see Table 3). The incidence of family daycare is relatively greater in regional areas than in metropolitan areas (see Table 4). Assuming family daycare is at full capacity of four preschool children and three school-age children per educator, the Department of Education numbers imply that the number of family daycare educators nationwide is just over 10,000, or an average of roughly 30 educators per family daycare service.

The question of overall excess or deficiency of supply is made moot by the lack of uniform distribution by jurisdiction: there are regional ‘deserts’ and ‘oases’, with the deserts being neighbourhoods where it is unviable to open a centre and/or where staffing is unavailable. A study by the Mitchell Institute at Victoria University points out that supply is greatest where the centre is able to charge higher fees, although the higher fees will also be correlated to some extent with higher costs of doing business.[25] Clearly, staffing shortages will have an influence on the operations of centre-based childcare places, while other factors will be primary drivers of the availability of family daycare. The peak body for the latter complains that the fee caps for childcare subsidies introduced in 2018 were biased against family daycare and had resulted in a steep decline of educators and endangered the entire industry.[26] The ACCC 2023 inquiry cited earlier finds, in line with this, that “There is little financial incentive for family daycare and in home care educators to enter or remain in the sector, as effective wages are below comparable award rates for other forms of childcare … The family daycare hourly rate cap is also unlikely to be sufficient to adequately cover costs and recompense educators” (p. 7). (The fee cap for preschool children attending a family daycare is $1.05 lower per hour than for centre-based childcare. The provider can charge above the cap, but the parent pays the difference out-of-pocket.)

2.4.1 Demand stress

The demand for paid childcare in a specific region is influenced by numerous factors, including region-specific labour supply preferences of families, general economic conditions, and the strength of informal networks that can provide unpaid childcare. In spite of these real-world complexities, childcare demand stress is typically gauged roughly by calculating how many paid childcare spots are available per child, by age group.

The Mitchell Institute study cited above provided data supporting the contention that the supply of childcare places is becoming less of a concern, despite claims that there is a desperate shortage of providers. Examining supply over the four years since 2020 when the study’s authors conducted a precursor study revealed that the number of childcare places had increased by about 10% while the population of children under five had not grown. Thus, while in 2020 34% of regions were classified as childcare ‘deserts’ (more than three children per childcare place), that figure had dropped to 24% by 2024. The supply/demand ratio had improved in all states/territories except the ACT (where supply/demand imbalance was already quite insignificant) and Tasmania, where the percentage of regions classified as deserts remained the same at 57%. Even so, the study may be biased toward overestimating the problem because it excludes family daycare.

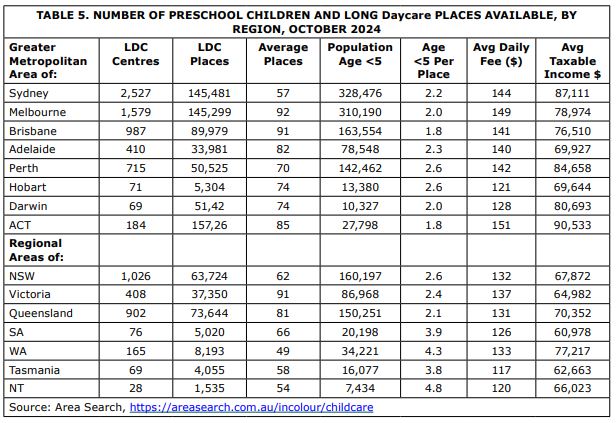

Geographic information systems consultancy Area Search maps childcare availability to population, and a summary of these data is reproduced in Table 5 below. It indicates that excess demand for places is most prevalent in the regional areas of WA, SA, Tasmania and NT. Except for WA, family incomes in these regions are among the lowest in Australia. Regional NSW and Victoria also appear to have a moderate but less severe shortage. Of the capital city metropolitan areas, only Perth and Hobart are approaching childcare desert status.

Childcare is most plentiful in the ACT and Greater Brisbane, while the two largest cities of Sydney and Melbourne are not far behind.

2.4.2 Staffing supply: Is there a skills shortage?

According to modelling work commissioned by Jobs and Skills Australia, as of September 2024 there was a shortage of 21,000 childcare professionals to meet current demand and a further shortage of 18,000 to meet expected demand over the next 10 years. It cites data showing that the vacancy rate for childcare workers rose sharply after 2019 but then began to level off and show signs of normalising in 2022-23. It also cites data indicating that the vacancy rate in regional areas is higher than in the cities, and data revealing lower remuneration rates for childcare workers than for those in other similar jobs, such as preschool teachers.[27] Its detailed report on the childcare sector is heavily laden with recommendations for initiatives by governments to boost the number of childcare professionals and improve the content of the education and training of care providers. Retention of childcare workers is a perceived problem, as reflected in the two-year Worker Retention Payment newly offered by the Commonwealth government in 2024 that subsidises 15% above-award-rate wages for childcare workers, paid through the CCS — though notably, workers in family daycare are not eligible for this payment.[28]

2.5 Measuring outcomes

How does one evaluate the impact of Australia’s present policy settings on our children’s development? Several attempts have been made to measure young children’s developmental progress and/or school readiness, of which I review a selection below.[29] I also review reports from organisations that might be expected to suggest practical metrics but have instead suggested dimensions that might be evaluated in ways that are left unspecified.

2.5.1 Australian Early Development Census (AEDC)

The AEDC is a national census of early childhood development conducted once every three years. This survey “looks at five areas of early childhood development: physical health and wellbeing, social competence, emotional maturity, language and cognitive skills (school-based), and communication skills and general knowledge”.[30] The data are collected from first grade schoolteachers and take the form of survey responses to around 100 questions about the children under their supervision. The last AEDC was conducted in mid-2024 and results will become available this year. The 2021 AEDC tabulated results for 305,000 children and was summarised by the Department of Education as follows:

“At a national level, the AEDC data shows the percentage of children who were on track on 5 domains decreased for the first time since 2009 (from 55.4% in 2018 to 54.8% in 2021). Results also show a slight increase in the proportion of children who are developmentally vulnerable:

- Children assessed as developmentally vulnerable on one or more domain increased from 21.7% in 2018 to 22% in 2021

- Children assessed as developmentally vulnerable on two or more domains also increased from 11% in 2018 to 11.4% in 2021.”

A full report on the 2021 AEDC is available online.[31] The results from 2009-2021 show little deviation over time.[32] Although the recent dip occurred after the Covid era and there are a number of other factors at play, of which childcare is only one, these lacklustre results — from an outcome-measurement system that is structurally divorced from the childcare sector, and hence likely not captured by special interests wishing to protect this sector — suggest that the present childcare quality assurance regulatory regime may not be optimal.

2.5.2 Other measures

The OECD suggests a five-dimensional approach to, in their words, “building [early childhood education and care] systems that foster quality in children’s everyday experiences from their interactions with their environment”.[33] The referenced dimensions are curriculum and pedagogy; workforce development; quality standards, governance and financing; monitoring and data; and family and community engagement. However, like many other public statements about what we would like to achieve in early learning environments and how to do so, this guidance is aspirational and cannot be used in a practical sense to measure quantitatively how well children are faring in a particular country’s childcare sector relative to those in another country.

The Australian Commonwealth government has developed an Early Years Strategy 2024-2034 and a set of measures to evaluate eight outcomes, of which six are directly relevant to child development: that children are nurtured and safe; that they are socially, emotionally, physically and mentally healthy; that they are learning; that they have strong connections to culture; that they have opportunities to play and imagine; and that their basic needs are met. These strategic goals are not directly related to childcare outside the home, although the quality and quantity of childcare experiences would feed into the outcomes.[34] The Australian National Early Learning and Literacy Coalition published materials nominating four ‘priority areas’ that describe what is important for children’s optimal development, which served as the framework for the National Early Language and Literacy Strategy that this coalition proposed in 2021.[35] However, the coalition formally disbanded after producing this strategy and was not in the business of measurement.

The Commonwealth Department of Education does have a Preschool Outcomes Measure being trialled this year.[36] This measure is still under development and is intended to help educators gain insight into the progress a child is making against learning standards in ‘executive function’ and ‘oral language and literacy’. Once ready, the Department notes that participation in the trial by childcare services will be voluntary, and that results from the trial will be used to inform further implementation.

2.6 Measuring returns to Australia’s childcare policy

As briefly discussed previously, a natural target for an economist wishing to evaluate Australia’s investment into childcare would be to estimate a return on investment. How might we proceed to do this?

In my view, recovering a reliable numerical ROI for the money governments presently spend on intervening in the childcare market is not viable, for a number of reasons. First, apart from a few studies cited in this report that link disadvantaged children’s early experiences to their later-life outcomes, we simply do not have good measures of how children in childcare versus not in childcare fare on average in terms of total lifetime incomes, health, happiness, or really anything we might care about and are able reasonably to quantify and monetise.

Second, even if we had information on how beneficial or harmful it was on average for children to be placed in childcare outside their own homes, it is not as though the government is investing in something that would not otherwise happen. Childcare markets would still be there (whether formal or informal, paid or unpaid), and might operate even more efficiently if governments were less, or differently, involved. This is also worth bearing in mind when considering whether the present amount of government regulation of the sector, reviewed in detail in the online appendix of this report, is optimal.

Hence, government expenditure on childcare does not have the features of a traditional ‘investment’ in which the investment itself can be directly tied to producing something that would otherwise not be produced. (For example, as noted briefly in the next chapter, there is even a disagreement in the literature about whether it is childcare availability, or conversely just broad social norms, that has driven up female labour force participation since the mid-1970s.)

Also, many recent reports and analyses, of which some are reviewed below, indicate that government intervention itself, in the form of demand-side subsidies, has been observed over the recent past to influence the apparent cost of care. The government is evidently not a price-taker but a price-maker in the childcare market, as government investment itself arguably reduces the net return earned per dollar invested.

Another problem is that much of what one would desire to eventuate from government intervention in the childcare market in the short run, like accessibility or quality of paid care alternatives, is not quantifiable in terms of dollar values except by very ham-fisted and attackable ways, like valuing each hour of accessible care at the average female wage.

For all of these reasons, trying to generate even a rough ROI determination is a fool’s errand, in my view. However, one may still reasonably ask a question about the likely sign of the effect: is government involvement in providing childcare likely to generate returns over and above what would be generated if the government did not intervene at all?

Let us think for a moment about this question from a simple logical standpoint, based on what is known about the likely value of care to different sorts of children and the economic value of having different sorts of women enter the paid labour force. Suppose the child’s family is advantaged, in the sense of being able to offer a developmentally appropriate home to the child. In this case, subsidising care is likely to have lower returns (due to a lower — or even negative — marginal value of paid care compared to the already good unpaid care the child would receive at home) than if the family were disadvantaged. Now suppose that the mother would pay high taxes and be very productive if employed outside the home. In this case, subsidising care is likely to have higher returns, in the form of hefty tax receipts and efficiency gains, than if the mother would not pay these taxes or be highly productive if employed. These two forces often operate in opposing directions, since advantaged families tend to be those that on average earn more money and hence pay more taxes and are more productive at everything, including both raising happy and productive children, and working in paid jobs.

I would confidently say based on simple logic plus the results of what limited research exists linking quality childcare to later adult outcomes (e.g., Campbell et al., 2014,[37] Barnett and Boocock 1998,[38] Mitchell et al., 2008[39], Muennig et al., 2011[40])[41] that there are significant public and private lifetime returns to children in the worst home circumstances of being able to attend high-quality paid care — care that may not be accessible to their families via the private market — and that for this reason of market failure, some government support for the provision of high-quality out-of-home care for such children is likely to be a wise social investment. Economic logic would support additional public subsidies in the case of efficiency gains of drawing high-productivity women from unpaid care of their own children into the paid labour market, and to the extent that carers looking after groups larger than a family can exploit returns to scale in providing childcare. This, of course, is conditional on the quality of paid care being no lower than what would otherwise be provided at home and on these gains not being fully absorbed by the private actors themselves.

3. Evidence from academic research and overseas experiences

3.0 A large body of research

A large volume of international research has been produced over the past 50 years — since women started entering labour markets in Western society in large numbers, and modern empirical analysis methods became available — investigating the connections between both paid and unpaid childcare and the outcomes with which this care is associated. As sketched in Chapter 1, these outcomes include child development (sometimes proxied by the nature of children’s experiences in care) and parents’ (and especially mothers’) labour market outcomes, and to a lesser extent society-wide fertility or family formation, women’s or families’ outcomes more holistically, and labour market outcomes in the childcare sector.

Impact estimates reported in the literature are typically calculated relative to baseline outcomes, where this baseline may be, for example, the development of children not attending paid care/preschool, or attending fewer hours of paid care/preschool, or the labour market participation rate of mothers whose children do not attend paid care. Impacts are generally reported as average effects, or average effects for particular demographic subgroups (e.g., children from disadvantaged families), but one should bear in mind that different children are likely to have different needs and hence to respond heterogeneously to different care situations.

In this chapter, my goals are first to review recent and well-established findings in these areas, whether built on Australian or overseas data, and then to examine the different features of the childcare systems, and their correlates, in a selection of peer nations. Australia may be able to draw lessons for the design of our systems from both findings in the international research literature, and from examining how else childcare might be done. What is not reviewed in this chapter is any of the voluminous scholarship about what specific features of a child’s experiences are more or less helpful for his or her development, with my treatment of this question being limited to high-level features such as what type of care setting the child experiences at what age (for example, family daycare versus centre-based care, or ‘high-quality’ versus ‘low-quality’ care as judged by available summary measures).

3.1 Academic and policy research by Australian researchers

Several research teams within government, at universities, or in think tanks in Australia have produced or are presently working on studies of childcare, often though not always using Australian data. A selection of the richest and most recent of these studies is detailed below, together with a brief summary of their findings.

- The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare produced a working paper in 2015, entitled Literature review of the impact of early childhood education and care on learning and development, a meta-analysis of existing studies that offers arguably the most comprehensive view presently available of the link between childcare and children’s outcomes in Australia.[42] Breaking the reviewed studies into those that focused on children aged 0 to 3 versus on those 3 to 5 years of age, the author (Alison Watter) found in several studies that experiencing ‘high-quality’ paid childcare was associated with positive developmental outcomes, particularly for children from disadvantaged backgrounds. Negative impacts on development were found to be associated with attendance at ‘low-quality’ care. On the intensive margin, spending more hours in paid childcare was found to be associated variously with positive and negative developmental outcomes, depending on the study. For children aged 3 to 5 years, attendance at childcare was found robustly to be good for development, especially if children were from disadvantaged backgrounds (for whom being mixed with children from other backgrounds was also found to be beneficial). Quality was found to be vastly more important than quantity of paid care experienced in determining children’s outcomes; and provision of high-quality care for children was found to be a massively beneficial investment from a whole-of-society perspective. Still, on p. 8 of this report, it is stated that “[h]ousehold income, parental and particularly maternal education and the home learning environment are the strongest predictors of children’s developmental outcomes”. How ‘quality’ is defined varies by study, but the report notes that quality has been “established by extensive research as including the following elements: group size, staff to child ratio, supervision level, teacher sensitivity, richness or quality of staff interactions, learning and emotional climate, curriculum content, and teacher or caregiver qualifications”. Notably, several items on this list do not seem easy to verify by a third-party quality assurer without regular intensive and unannounced site visits, and the list does not overlap perfectly with the contents of Australia’s National Quality Framework. Also relevant to the definition of quality, “having nurturing, warm and attentive carers is the most critical attribute of quality in any childcare setting, especially for younger children,” according to the author of this report (p. 9).

- The Murdoch Children’s Research Institute and collaborators released a review in 2019 entitled Early childhood education and care: An evidence based review of indicators to assess quality, quantity, and participation.[43] The authors reported that judged against the National Quality Framework, fewer than half of the care facilities in Australia in 2018 were rated as ‘exceeding’ the standards set in the various areas, and only 25% received this rating in the three dimensions of quality that the authors concluded were most important to children’s development (while also at least meeting stipulated standards in other dimensions). This may indicate that the de facto primary function of the NQS is to identify poor performers, rather than to reward, and hence stimulate centres striving to be, outstanding performers. The authors also synthesised their literature review into a recommendation that part-time, high-quality care was almost surely good for the development of children two or fewer years from starting school, carrying the implication that funding such care would be a sound investment for the government.[44]

- In a chapter entitled Designing public subsidies for private markets: Rent-seeking, inequality, and childcare policy within the 2022 volume Designing Social Service Markets: Risk, Regulation, and Rent-seeking, Adam Stebbing[45] reviews many recent scholarly and policy contributions on the usage and consequences of Australia’s childcare sector and notes that since the major shift almost 40 years ago from public to private provision of childcare in Australia, public childcare subsidies have flowed into private pockets, with at least some of this flow fairly termed ‘rent-seeking’. Stebbing reviews the varied opinions on the success of this change, noting that while childcare coverage has expanded, “mounting evidence supports persistent concerns about limits to the availability and affordability of quality childcare services as profits for providers have soared in the past two decades” (p. 302). He examines the various formats of demand-side subsidies employed by successive governments and their apparent impacts and concludes that “childcare policies that more closely resemble direct expenditures have been less inefficient and more equitable than those that possess features of tax expenditure” (p. 302), meaning those tied to tax assessments or rebates. He further suggests, based on a review of the impact of the three months of universal childcare provided during the Covid era via conditional supply-side subsidies, that fruitful directions of reform targeting more equity and less rent-seeking could involve imposing conditions, such as capping the out-of-pocket fees charged by a centre that receives public (supply-side) subsidies, and/or prohibiting gap fees from being charged to low-income households by such centres.

- Chrystal Whiteford, a PhD student at Queensland University of Technology, undertook a study entitled Early childcare in Australia: quality of care, experiences of care and developmental outcomes for Australian children[46] in 2015 using the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. In her thesis, which features a voluminous literature review, she finds of note that:

(1) the quality of childcare is hard to define, hard to measure, and hard to assure, as captured in the statement on p. 45 that “Observational measures are often considered a more reliable measure of quality in childcare settings [relative to structural measures that do not require direct observation]. However, due to increased costs associated with observational measures alternate forms of measuring quality are required”;

(2) children who experience centre-based (rather than parent or home-based) care, and/or whose intensity of care was high, particularly as an infant, were more likely to experience several conduct problems, lower language and literacy, and ill health at ages 6 or 7; and

(3) the presence of two parents in the home, and other variables about the child (such as sex) and home situation (such as socio-economic status), were more predictive of later-childhood outcomes than anything about childcare experiences. Whiteford (2015) also finds some evidence in support of the notion that average childcare quality in Australia is, while not bad, also not stellar, but surprisingly little evidence that measures of quality of care when young are determinative of academic, social or health outcomes at age 6 or 7.

Certain Australian authors have established a track record of contributing high-quality, policy-relevant research on matters related to early learning. Perhaps most prominent amongst these is Robert Breunig. In his most recent published work on the topic, Gong and Breunig (2017)[47] apply a structural model of labour supply and childcare demand to Australian data to compare the impacts of direct childcare subsidies to tax credits. They find that direct subsidies are less efficient but more re-distributional than tax credits, which are more effective at unlocking labour (disproportionately the labour of better-off women) and raising household income.

Finally, a brief mention is in order about what can be concluded about the comparative quality of family daycare and centre-based long daycare in Australia. Some institutionalised daycare industry advocates have claimed that family daycare is less safe for children, and/or incapable of providing educational enrichment, relative to institutionalised care. One source claims that in the last 12 years, there have been two deaths of children in New South Wales daycare settings — one in family daycare, and the other in long daycare — and concludes that because the number of family daycare services is only about 5% of the number of long daycare services, family daycare is therefore less safe. The first point to make is that drawing such a conclusion is unwarranted because of insufficient observations: one death in each setting is simply too few to go on, regardless of the number of settings of each type.

The second point is that examining child deaths across the state in aggregate makes clear that if the statistics above are correct, then compared to any type of paid care setting it is far more life-threatening for a child in NSW to be cared for in his or her home.[48] While accidents and deaths do occur when children are in care, and reported incidents may be higher in family daycare settings than in institutionalised care settings,[49] the absolute numbers are very low.

The final point to make is that child deaths are only one, very extreme, measure of safety. Such are the perceived quality problems in the childcare industry today that the Australian Broadcasting Corporation ran a documentary in March of this year about the poor care quality received by children in childcare centres, in which for-profit centres were found to feature “child abuse, neglect, and injury, highlighting critical gaps in childcare safety and accountability”.[50] A review of the documentary by Marg Rogers sets out the reasons, to do with profit-seeking, careerism, and accountability, that may underpin the poor quality of care particularly at some for-profit long daycare centres,[51] something also highlighted in several other recent reviews and news reports.[52]

These reports have been sufficiently alarming to the public that several Australian state governments have taken responsive action in recent months, including a “snap review” undertaken by Victoria. The final report from that review recommends, both to the state and to the Commonwealth, more monitoring and regulation: establishing a national abuse register and a new “national reform commission”, mandating more CCTV coverage, strengthening the Working with Children Check system and mandatory child safety training for workers, and increasing staff requirements.[53] The connection between these actions and improving the health and safety of children — like the connection between the National Quality Framework as a whole and childcare quality, as mentioned earlier – remains unproven.

3.2 Academic and policy research using overseas data

Australian policy discussions, whether about childcare or other areas, frequently omit entirely any consideration of what peer nations are doing, and thereby miss the chance to learn from both mistakes and successes experienced overseas that may be valuable inputs to our domestic policy-setting. Keen not to repeat this mistake, I review here some findings from other countries that help to contextualise what is going on in Australia with regard to the childcare sector and childcare policies, and may help inform the development of fruitful reform directions.

Zollinger and Widmer (2020)[54] observe that the many different styles of childcare available in different Swiss regions may have arisen due to the different framing of the purpose of childcare employed by those in political power in the different regions. The frames suggested are ‘social integration’, ‘labour market’, ‘gender equality’, or ‘poverty reduction’ (also termed ‘male breadwinner’). The authors make specific suggestions of care formats that correspond best to each of these frames. It is not unreasonable to expect a similar link to exist over time and/or across regions between political messaging and policy design in other countries, including Australia, underscoring the importance of differentiating between political or ideological rhetoric and fundamental economic realities in examining childcare markets and proposing reforms.

Griffen (2019)[55] builds a structural model of families and care options calibrated to mimic American policy settings and applies this model to real US data. He finds that counterfactually expanding access to a relatively high-quality early learning program that has traditionally focused on serving disadvantaged children, called Head Start, is (perhaps unsurprisingly, given the findings already reviewed in this chapter) expected to improve children’s developmental outcomes. By contrast, he finds that simply expanding childcare subsidies has no effect on child development, but positively affects maternal labour force participation, which he interprets as indicating the lack of a trade-off between these two different goals of childcare.

Similar qualitative conclusions are reached by Albanesi et al., (2022)[56] using data from across Europe. These latter authors also emphasise that the impact of paid childcare on child development depends crucially on the counterfactual situation of the child in question, recognising that either situation (unpaid parental care or paid childcare) may be superior.

Sluiter et al., (2023)[57] find that child wellbeing is higher and problematic behaviours lower in home-based care than in centre-based care for their study sample of children under 40 months old, and that what the authors term ‘process quality’ (as opposed to ‘structural quality’, the latter being more easily measured by top-down quality assurance mechanisms such as the one in place in Australia) is more related to child functioning in home-based as opposed to centre-based care.

A Canadian review from 2019 goes so far as to claim that “[t]here is a general consensus that process quality in [early learning and childcare] settings is the primary driver of gains in children’s development”.[58] Sluiter et al., (2023) also find that the “quality of the dyadic relationship” (i.e., the relationship between child and carer), a specific component of the domain of process quality, was associated with higher child wellbeing and fewer problem behaviours for the very young children in their sample, something highlighted in Schoch (2023),[59] who writes: “The characteristics of high-quality ECE often look different for infants and toddlers than for older preschoolers … [I]nfants and toddlers show greater developmental gains when they experience continuity of care (i.e., the same caregiver over time; for example, over the day or week, or from year to year)” (p. 5).

Similarly, Burchinal et al (2016) review eight large published analyses of the link between various measures of care quality and care dosage (i.e., hours per week) with preschool children’s outcomes in the domains of language, literacy, mathematics, and social skills.[60] The authors find that more exposure to high-quality care is better for disadvantaged children, which is unsurprising if every hour of high-quality care substitutes for an hour of lower-quality care that the children would counterfactually receive in their home environment. These authors also find that child outcomes are not affected by what they call ‘global’ quality measures, i.e., physical features of the environment and other features more easily gauged by a bureaucratic quality-measurement system, once they account for the instructional and emotional quality of interactions between children and carers. The quality of these interactions, by contrast, is strongly related to child outcomes.

In Australia, we would be wise to bear in mind the likely higher returns available to providing high-quality care, even at doses much higher than targeted by the present ‘Universal Childcare’ proposal, to children in disadvantaged family situations. This includes many children in regional and remote Australia and those growing up in cultural environments that are not associated with high intellectual achievement, social skill development, or later-life wellbeing. We would also do well to bear in mind the importance to child wellbeing of the quality of the carer-child relationship, and of facets of the childcare setting apart from easily measurable structural factors, particularly for very young children.

Scherer and Pavolini (2023)[61] examine the connections between maternal labour force participation, maternal education, and the prevalence of public childcare at the region level in 20 different European countries from 2000 to 2019. These authors find that increased coverage of public childcare was associated, likely causally, with economically meaningful increases in maternal labour force participation, particularly for less-educated mothers and particularly in the form of increasing full-time employment. Narazani (2023)[62] builds a structural model to estimate the impact of increased childcare provision on maternal labour market participation in Europe, finding — like Scherer and Pavolini (2023) — that the estimated impact is positive, especially for countries with initially low levels of paid childcare.

However, Pasternack and Cook (2024)[63] (Chapter 1) note that maternal labour force participation in the UK has steadily risen since the mid-1980s, starting well before the modern system of childcare subsidies, and that the proportion of non-working mothers who say they would like a job has stayed relatively fixed. The authors observe on the basis of these patterns that broader cultural, socio-economic, or demographic changes — rather than the specifics of the paid childcare and parental leave systems — may be the main factors responsible for the observed historical trends in maternal labour force participation rates. These same authors report that large fractions of the UK public believe that children are best off spending time mainly with parents until their second birthday, and see finances as the main barrier to organising their own child’s life in this way (Chapter 2). Bearing in mind these results, Australian policymakers should not immediately assume that childcare is the only factor constraining women’s labour market participation choices, and should be aware that the change in measures like women’s hours of work that may flow from improving childcare access is likely to fall as starting levels of both childcare access and women’s hours of work increase.

3.3 International policy experiences

In this final section of Chapter 3, I review a selection of work that describes and evaluates the specific features of childcare systems in several of Australia’s peer nations overseas, focusing on what lessons may be gleaned from these systems that could point towards potential improvements in Australian policies. Naturally, many other policy, economic and cultural settings differ between Australia and overseas countries, and so the comparisons here are provided mainly to expand our understanding of how the problem of caring for children could be addressed, and subject to the caveat that wholesale adoption of another country’s policy would likely not result in the exact same outcomes in Australia, due to such differences.

3.3.1 United States

In the US, which is known for its comparatively miserly family leave policies, Kang et al., (2002) find that the availability of paid family leave in California (at a still arguably miserly rate of 55% of income paid for eight weeks) made it more likely that women, including low-income women, would be employed a year after their child’s birth. The stated goal of California’s paid family leave policy was to provide a particular type of insurance, theretofore unknown or very modest, to workers and families.[64] Similar effects on maternal labour force attachment may not be created by increases in parental leave policies in Australia or other OECD countries, whose baseline levels of parental leave are far more generous already. For a review of such policies, see Ramoso and Hill (2023).[65]

In a series of blog posts in 2023, Bick et al[66] at the Federal Reserve of St Louis examined the rebound of labour force participation after the Covid era amongst various sub-categories of workers, including women with young children, older workers and so forth, looking to test the hypothesis that participation had declined post-Covid because of the observed rise in childcare prices and decline in the number of childcare workers (implying lower accessibility of care).

The authors find that difficulties in securing childcare are unlikely to be responsible for the aggregate observed reduction in labour force participation — as the participation of married women with young children has in fact rebounded strongly relative to other groups — and that it is instead mainly those 55+ who have pulled away from the labour market post-Covid (and for this group, the lack of gender difference in the decline in labour force participation indicates that an increase in grandparent-provided care is unlikely to be responsible for this decline). Again, this result may temper our expectations about the degree to which changes in the Australian childcare sector will move the dial on women’s labour force participation.

In very recent work, Pepin (2024)[67] finds that expansions in demand-side childcare subsidies in the US starting in 2003, designed to help offset the rising costs of childcare for working families, increased uptake of care and also led to a rise in married maternal labour force participation. In a similar vein, Jasinska (2024)[68] examines the effects of demand-side financial intervention on the utilisation of care and/or the availability of care, cognisant of the fact that in the US, a significant amount of pent-up demand exists in low-income families due to the low accessibility of affordable care. Families with pent-up demand by definition are using either in-home care or informal (unpaid) care by others, but would prefer to use paid care, if they could afford it. The specific demand-side policy reviewed is a tax credit, which the author advises enhancing to make it refundable, larger, and paid on a monthly basis rather than yearly to most effectively assist low-income parents on a strict budget.

The links found between childcare ’deserts’, undersupply of childcare workers, and income of parents in the Jobs and Skills Australia[69] study of workforce demand may be viewed as circumstantial evidence that Australian families living in these regions also experience pent-up demand.

3.3.2 Canada

The Canadian province of Quebec has a supply-side-subsidised childcare system, first introduced in 1996 with the intent to increase female labour force participation and improve women’s work-life balance, and to provide children, particularly those from low-income families, with greater developmental opportunities.[70] It also had the ancillary goal of boosting government revenues by enticing more tax-generating workers into the economy. The system involves a flat fee of close to A$10 per day at current exchange rates, which compares to the national average fee of about three times that amount. Quebec’s participation rate in childcare is accordingly significantly higher than the national average, with approximately 70% of children aged 0-5 in care, compared with the national average of 50% (Productivity Commission, Vol. 3, p. 32). The Canadian government’s policy is to bring the other provinces into line with Quebec. The provinces have signed a formal agreement with the federal government to have the A$10 fee model in place by 2026. (Productivity Commission, Vol. 3, p. 32.) The province of British Columbia is piloting 12,000 publicly funded places at ‘prototype sites’ — forming a pilot of switching to a supply-side funding model — along with additional incentives for public and not-for-profit centres to expand, particularly in under-served regions (Productivity Commission, Vol. 3, p. 36-37.)

Cherry (2024)[71] compares the childcare systems in Quebec and NSW, finding that the lower out-of-pocket fees paid by Quebeçois households are associated with higher-intensity care use by children and also with much stronger attachment (more participation, and higher hours of work) for mothers in Quebec, relative to mothers in NSW. However, taxes on the Quebec population have risen alongside the switch to supply-side funding, a correlation that may be partly causal.[72] In addition, concerns have been raised about the quality of care provided to children in the Quebec system, with some research indicating a lower overall quality of care and decreased accessibility of care to low-income parents (due to substantially increased demand) after the introduction of the supply-side model.[73] Fortin (2017) provides evidence that care quality problems in the Quebeçois supply-side system are concentrated in for-profit care centres, with centres that are directly overseen by local parents observed to deliver higher quality care.[74] This indicates that it is not the supply-side system per se that creates a care quality problem, but rather some combination of the governance or quality control system and the funding system. All of this evidence should be considered in light of the limitations of the top-down, bureaucratic quality measurement system (similar to Australia’s) that is the source of the quality measures analysed.

A critique of Cherry (2024) by Gordon Cleveland[75] notes the following about Australia’s childcare sector: “Every time the Commonwealth government pours more money into the system, out-of-pocket child care fees fall temporarily. After a short while, these out-of-pocket costs gradually rise back to previous levels.” Cleveland argues that the demand-side focus of Australia’s government intervention may be inferior to a supply-side focus as seen in Quebec, where centres receive operational grants directly from the government and fees are capped,[76] at least as far as producing low out-of-pocket fees and public accountability of funding. Another implication of this work is that Australian mothers’ labour force participation or work hours might respond strongly to actual reductions in childcare fees, even if these measures do not respond strongly to increases in subsidies (which ultimately are taken away from parents through higher fees). However, the Quebec experience suggests that any change in the direction of supply-side funding should be accompanied by the decentralisation of governance and/or quality oversight, in order to minimise the likelihood of a reduction in care quality.

3.3.3 Europe

In the UK, childcare policy has been governed by the overarching goals of improving outcomes for disadvantaged children, improving preparedness for school for all children, and increasing labour force participation.[77] Haux (2024)[78] observes that childcare policy was a major election issue that year in the UK. She analyses the state of the UK childcare market and concludes bluntly that “CEYP [the childcare and early years provision system] in England is not working for parents, providers or children in terms of its affordability, sustainability and quality” (p. 135). Her review of the policy proposals suggested by the major UK political parties and think tanks reveals a mix of demand-side or supply-side subsidy increases or expansions; adjustments to details of timing and format (e.g., changing the location of care or the staff-child ratio, extending the hours that care is available, or formalising more community support for caregivers); and reducing regulation. Clearly, Australia is not alone in its present struggles to set optimal childcare policies.

Lind (2021)[79] sketches the policies relevant to childcare usage in the Nordic countries, which aim to promote gender equality and equality of opportunity for children of all demographics. These policies include childcare market interventions as well as paid parental leave policies. What stands out in these countries’ policy landscapes, relative to those of peer nations including Australia, are:

(1) the pegging of fee caps to percentages of household income (for example, a maximum of 3% of household income);

(2) penalties on households in which fathers do not take any parental leave (with these penalties taking the form of the forfeiture of some number of days of paid parental leave);

(3) childcare is underwritten by governments universally, with no household- or parent-specific activity or income tests; and

(4) childcare services are often provided directly by government, or contracted out to private providers by government, and are commonly viewed as ‘critical infrastructure’ similar to wharves or roads.