Home » Commentary » Opinion » Confessions of an Industrial Relations Club reporter

· AUSTRALIAN FINANCIAL REVIEW

We’ve just heard a fair bit about the 50th anniversary of the sorry end of the Whitlam government. Next year comes the counter-anniversary: 50 years since the launch of the classical liberal think tank I now run, the Centre for Independent Studies.

Sydney maths teacher Greg Lindsay started CIS in 1976 amid the collapse of the post-war Keynesian consensus, the mad Whitlam spending spree, the first OPEC oil shock, the trade union-led wage explosion and the scourge of stagflation.

More personally, I confess that next year also will mark 50 years since I started as a cadet journalist on Adelaide’s The Advertiser and first encountered Australia’s unique industrial relations system.

As a former IR reporter and the longest-serving editor of an Australian national newspaper, I’m delighted to appear at conference that bears the name of the former editor of the Hobert Mercury who dared to robustly critique Australia’s industrial relations system

In the mid-1970s, the unions covered about half the workforce. Large-scale strikes were an everyday event, seemingly part of Australian culture.

As a teenage cadet journalist on Adelaide’s morning broadsheet newspaper half a century ago, I worked out of the pokey press room at the South Australian Trades Hall building on the city’s South Terrace.

Along with shorthand and touch typing, I learned the trade on the job from The Advertiser’s veteran industrial relations writer Bill Rust.

The Trades Hall animal farm was populated by the likes of the Amalgamated Metal Workers and Shipwrights Union (the AMWSU), the Shop, Distributive and Allied Employees Association (also known as the SDA or the Shoppies), the Federated Engine Drivers and Firemen’s Association and the unpretentiously-named Federated Miscellaneous Workers Union (or the Miscos). Miscos unite!

These worker bargaining agents also seemed to be rival political organisations. The Shoppies were anti-Communist and Catholic. The metal workers were left wing, even Communist like Laurie Carmichael. The Builders Labourers Federation was Maoist.

I felt physically threatened just once, by a fellow named Doyle from the Fire Fighters Union. The local Shoppies head, a fellow called Goldsworthy, warned me off suggesting the union might ban the popular Christmas pageant put on by Rundle Street department store John Martins. In contrast to Doyle, Goldsworthy’s warning didn’t bother me as he barely stood five feet tall.

Bob Hawke flew into town to seek to resolve a dispute in which the Australasian Meat Industry Employees Union was blocking the export of live sheep. The abattoir workers claimed the right to determine how farmers could sell their livestock.

The local press pack gathered around Hawke at the Adelaide airport’s VIP room. The ABC’s Trades Hall reporter thrust his microphone under the ACTU president’s face and asked: Mr Hawke, why are you in Adelaide? The future prime minister replied: ‘Well I haven’t come here to pull my pudd.”

I further confess that it’s 50 years next year that a promising young industrial officer also joined the Shoppies union in the South Australian trades hall. His name? Don Farrell.

Half a century on, the convivial Labor trade minister now tops The Australian Financial Review Magazine’s covert power list.

Coming from a DLP family, the Don remembers our shared time at Trades Hall well and insists that I was a leftie.

But it was also a disrupted time amid the collapse of the post-war full employment mantra that had been born out of the 1930s Depression. The 1970s collapse of this Keynesian consensus ensured that much of the IR debate was about macroeconomics.

Politics had become all about economics. So I combined cadet journalism with part-time economics study at the University of Adelaide which, by 1981, landed me in the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet in Canberra.

In his only budget just months before the 1975 Dismissal, Bill Hayden had said Australia no longer lived in a simple Keynesian world in which Treasurers like him could trade off a bit more inflation for a bit less unemployment.

That was after the unions, led by Hawke, had blown up the economy and Gough Whitlam’s government, even without Clyde Cameron, Rex Connor, Jim Cairns and Tirath Khemlani. Nominal average earnings jumped 68 per cent in three years, consumer prices rose 50 per cent and the profit share fell by four percentage points of GDP. The unions were his biggest problem, Whitlam told David Barnett at the 1974 Christmas Party at the Lodge.

After Governor-General Kerr dismissed Gough, Malcolm Fraser set about fighting inflation first, with tighter budget policy and money supply targeting inspired by Milton Friedman’s monetarism.

A small group of agitators pushed for an alternative to Keynesianism, protectionism and regulation, including the new Centre for Independent Studies, the Financial Review, the Modest Member Bert Kelly, the forerunner of today’s Productivity Commission, one or two dissidents in the Reserve Bank, some backbench Liberal dries including Jim Carlton and John Hyde and young Treasurer John Howard, who commissioned the Campbell inquiry into the financial system.

But Malcolm Fraser was a Black Jack McEwen or even Andrew Hastie-style industry protectionist and more of a conservative than a neo-liberal.

As shadow industrial relations minister, Fraser had urged workers to join their allotted union. He was an admirer of Keynes and debated his advisers, including David Kemp, over Friedman and Friedrich Hayek. He quashed his young Treasurer, Howard.

There was brief talk about ‘Americanising’ Australian industrial relations. But, after the second OPEC oil shock, Fraser embraced a Queensland and NSW-based coal energy boom that the unions once more blew up.

The result was that Australia was slow to deliver a neo-liberal response to the 1970s stagflation that in America produced Ronald Reagan’s supply side tax cuts and in the UK Margaret Thatcher’s defeat of the unions. By the end of the decade, Singapore’s Lee Kwan Yu warned we were in danger of becoming the poor white trash of Asia.

Meanwhile, at the Financial Review, black cape wearing editor PP McGuinness declared Australia had no alternative but to adopt an incomes policy to fight inflation and unemployment together.

Paddy previously had worked for then Opposition leader Hayden, who was interested in the idea. And then Paddy famously and correctly predicted across page one that Australia was heading into recession and perhaps a depression thanks to the unions and the Arbitration Commission.

The Financial Review’s industrial relations reporter Gerard Noonan took his family off to Italy. My background as an IR reporter, my economics degree and my year in PM&C convinced Paddy to give me the job.

So I joined the long heritage of Financial Review IR reporters, from George Negus, John Edwards, Neil Swancott and Larry Kornheiser to Pamela Williams, Stephen Long, Mark Davis, Mark Skulley and, today, David Marin-Guzman.

On my first day, I trooped down to Nauru House for the Arbitration and Conciliation Commission’s full bench national wage case, headed by Sir John Moore. Yes, one of the modern quasi-judges HR Nicholls previously had lampooned. The next day, April Foot’s Day 1982, my first Financial Review story hit page one.

The angle was that the employers’ advocate, the Confederation of Australian Industry, argued that the government’s tight monetary policy made businesses more vulnerable to union strikes and so might perversely provoke higher wages. It was a classic political economy Financial Review story outside the template of the IR reporter’s club.

As the predicted recession hit hard, Fraser called an election, hoping to catch Labor out. But Hawke moved on Hayden and then trounced Fraser.

At the National Economic Summit a month after the March 1983 election, I reported on page one how Hawke and the ACTU ran rings around the employer groups and leading company chiefs including Rod Carnegie and Arvi Parbo.

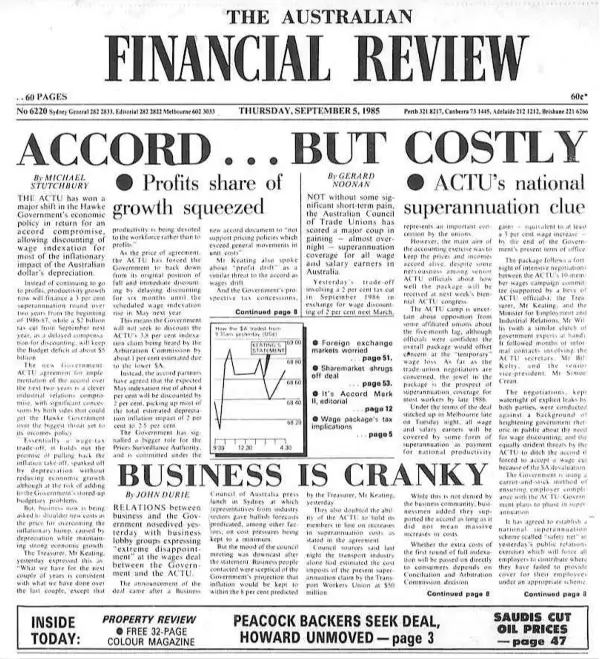

But, apart from a return to centralised wage fixing, in key ways, business did well out of Hawke’s Accord with the ACTU. The unions agreed to cut real wages and restore the profit share to revive business investment and reduce double-digit unemployment.

Labor right Treasurer Keating dealt with the Labor left by savaging the metal workers union for having destroyed 100,000 manufacturing jobs.

The neophyte Treasurer figured the wage Accord had given him the levers to control the macro economy.

And then came the big surprise. Keating turned the Accord into the foundation of the microeconomic reform agenda — the dollar float, financial liberalisation, a flatter tax system, lower import tariffs and privatisation.

An IR-based incomes policy became the vehicle for Australia’s version of the Reagan and Thatcher revolutions, delivered by the freakish personal combination of Hawke and Keating, the ACTU’s Bill Kelty and Simon Crean and mostly supported by the Howard-led Opposition.

This delivered the productivity dividend of the 1990s that put Australia on the path from also-ran to become one of the world’s most affluent societies. No small thing.

But the ACTU ensured the job market was spared the microeconomic shakeup imposed on other parts of the economy.

The reason was obvious. The job market regulations provided legal protection for the union monopolies that owned the centre-left political duopolist and underpinned the whole labour movement exercise of power and patronage.

The new Labor government quickly abolished the Bureau of Labour Market Research. And it commissioned a classic IR club inquiry that dutifully endorsed the benefits of entrenching centralised wage fixing and the award system.

Not surprisingly, that triggered a counter-reaction. Gerard Henderson popularised the Industrial Relations Club as a form of abuse, including the IR journos. Ray Evans set up the HR Nicholls Society.

The Labor-ACTU regime further provoked New Right campaigns such as the Robe River dispute to de-unionise the Pilbara and the Dollar Sweets case run by a young Peter Costello.

While the ACTU had to agree to tighten workers’ belts in the short term, the Accord delivered long-term strategic gains to the unions. First, in a rare break with Keating, Kelty vetoed the Treasurer’s Option C consumption tax at his 1985 tax summit.

And, hey, revealing Keating’s consumption tax plan had been one of my best scoops as an IR club reporter.

Second, the Accord Mark Two delivered 3 per cent superannuation payments into industrial award bargaining, touted as the distribution of productivity gains to workers. The unions cleaned up after Whitlam’s attempts to set up a government-based national super scheme fell short and after Fraser failed to produce a Liberal alternative.

On page one, a returned Gerry Noonan and I wrote this up as a big deal. But who could have predicted it was the seed that turned into Australia’s $4.3 trillion superannuation system, dominated by union-led industry funds?

But basing ‘default’ super in the IR system unfortunately has ensured that Australia’s long-term retirement incomes system remains politicised, full of governance issues and hence unstable.

By the early 1990s, Keating had knocked off Hawke and, even following another nasty recession, won the ‘true believers’ election of 1993.

He had deregulated the financial market and the product market. Now he and his IR minister Laurie Brereton sought to bring in enterprise bargaining to generate win-win productivity at the shop-floor level.

The Arbitration Commission judges resisted the loss of centralised wage fixing. But the unions still kept their privileged protections as Keating and Kelty tried to prove the system could be pro-productivity.

From 1996, John Howard and Peter Reith sought to correct Keating’s exemption of union monopoly privilege and the award system from the microeconomic reform agenda.

After the iconic waterfront dispute, Howard then used his thumping 2004 election victory to wind back the overall grip of workplace regulation and the unions themselves.

WorkChoices was nowhere radical enough for Ray Evans and was unremarkable in international terms, as Graeme Watson commented.

But, with no crisis to justify it, WorkChoices was too radical for the voters at the time.

And the Labor and union fightback even knocked off Kevin Rudd as Labor prime minister.

The union warlords instead installed former industrial lawyer Julia Gillard, who kissed the ring of AWU over-lord Bill Ludwig and declared the ALP to be a Labor party, not a social democrat party.

Yes, the IR system and its wage bargaining process had been disciplined by the dollar float, financial liberalisation and the dismantling of the import tariff wall. Union membership had fallen sharply.

But the Rudd-Gillard Fair Work Act restored order by knee-capping Keating’s enterprise bargaining and reinforcing the award system, the union movement’s safe harbour.

When I returned to the Financial Review as editor in chief in 2011, I latched onto a devastating confession from one of my 1980s contacts within the IR Club.

Australia’s “workplace relations architecture is essentially an attempt to institutionalise conflict, not to forge productive workplaces,” confessed Anna Booth, the former head of the Textile, Clothing and Footwear Union.

On the back of Booth’s oped in the Financial Review, I ran a mini campaign against the outdated assumption of an inherent conflict between the defenceless labour proletariat and powerful capitalist cartels.

Labor’s workplace minister at the time, Bill Shorten, shut up Booth’s talk by appointing her as a deputy president of the Fair Work Commission.

By 2012, Australia had experienced an unprecedented two decades of unbroken and low inflation economic growth. Thanks to the productivity dividend from the 1980s and 90s neo-liberal reforms, and then the massive national pay rise from the China boom, Australia had not only avoided becoming the white trash of Asia.

We had become one of the world’s most affluent nations, with per capita income higher than the UK, Germany, Sweden and Japan.

But the over-prescriptive IR system has contributed little if anything to this modern prosperity. And now the retreat on industrial relations, along with other policy failures, means this prosperity has been sliding for nearly a decade and a half.

After Tony Abbott won power in 2013, Dyson Heydon’s royal commission exposed the institutional corruption of labour supply monopolies such as the Health Services Union and of course the construction division of the CFMEU. Who could have known that the CFMEU harboured criminal bikie gangs?

But, from the Catholic right, Abbott was not a labour market neo-liberal. And, to this day, the capital L Liberals remain paralysed by WorkChoices.

When Albanese Labor won the 2022 election, it should have been obvious to business groups that, as in 1983, they were heading into a stitch up.

The 2022 Jobs and Skills summit was Whitlam acolyte Anthony Albanese’s insurance policy against Rudd’s fate. Before business had blinked, the summit effectively rubber-stamped ACTU demands for a return to pattern bargaining and the so-called same job, same pay legislation that targets BHP and Qantas.

Compared to the 1970s, the problem now is not so much high inflation and high unemployment. Now we have an independent Reserve Bank to deal with inflation.

Demographic changes mean that close to half a century of insufficient demand for labour is now giving way to chronic shortages of labour, including for construction workers to build all those houses we need.

The problem is more about the weak microeconomic growth foundations. Labour productivity is stuck at 2016 levels. The RBA has lowered its estimates of Australia annual economic growth potential to just 2 per cent. The budget faces a projected decade of deficits, even without an increase in defence spending.

During this year’s election campaign, I asked Labor’s then Workplace Relations Minister Murray Watt whether he would concede that “if we don’t get a pickup in productivity, there will be a limit on getting further real wage increases”.

Workplace Relations Minister Murray Watt

Part of Labor’s political mythology is that it can regulate wages higher, even in real terms.

So Watt rejected my proposition saying that: “I don’t think it’s correct to say you can’t have real wage growth without stronger productivity growth”.

This becomes even more unlikely now that Australia has lost the cheap energy advantage that previously helped us run a high wage economy.

Cheap coal-fired energy attracted the capital to build a string of nickel, copper, aluminium and lead smelters and the like in the 1960s, 70s and 80s. Now these smelters are either going under or being propped up by taxpayers. Not much of a Future Made in Australia there.

Australia got rich exporting close to one billion tonnes of iron ore each year. But Labor’s IR changes are now allowing the unions back into the Pilbara. The last time that happened, the Japanese steel mills bankrolled the Brazilian iron ore industry as a more reliable alternative and Bob Hawke had to tell the shop stewards to back off. 17.35

Australia still persists with its unique phenomenon of 121 so-called modern awards, dictating thousands of prescriptive work classifications, minimum wage rates, allowances and penalty rates that even snare such self-righteous employers as the ABC in supposed systemic ‘wage theft’.

But there’s something else. At CIS, it’s my assessment that today’s regulatory challenge is qualitatively different to the 1980s agenda of floating the dollar, deregulating the financial system, lowering the tariff wall, privatising the Commonwealth Bank and the like.

We know about the explosion of red tape and, for instance, how many licences are required to set up a local coffee shop – answer 36 in Victoria. 19.45

But today’s regulatory burden also is more about the state requiring businesses to do things on top of their actual business of delivering goods and services that customers are willing to pay for.

Hence, companies are required to reduce the carbon emissions of their customers in another country. To police global supply chains to eradicate modern slavery. To become conscripted agents of law enforcement, such as against money laundering, and cop massive fines for relatively innocent breaches.

This new regulatory compliance burden makes it more difficult to offer new home loans, to build more houses, to install renewable energy investment, or to open a new mine or gas field. The Macquarie Group’s estimated annual compliance bill has been as high as $1.2 billion.

Or business is supposed to drive social change by ensuring gender equality – or to be responsible for the mental health of its workers.

A whole set of new regulatory rights is accumulating on top of the traditional employment contract. The Fair Work Commission rules that Westpac must allow an employee to work from home five days a week because it’s not convenient for her to come into the office.

Now the NSW Safety Regulator is interfering in basic business operations.

The Federal government has cut back on foreign students. That’s hitting the universities’ revenue line, forcing them to reduce their costs.

But Safety NSW slapped a “prohibition notice” on redundances at a Sydney university because it exposed academics to ‘serious and imminent risk of psychological harm’. What would a private business at risk of trading insolvently do in this no-win regulatory conflict?

Australians have shown they are comfortable with a Whitlam-lite increase in the size of government and even with legislation to guarantee they can work from home.

The Liberals couldn’t even prosecutive the political case against giving taxpayer-funded fat cat public servants the right to never come into the office.

But, in an echo of the 1970s, the Australian economy will continue to under-perform. As the disappointment mounts, so will the demand for genuine productivity reform, as it did back then.

Jim Chalmers sort of knows this, which is why he is searching for Labor-acceptable productivity policies — such as the ban on non-compete clauses announced in this year’s budget.

But this is just a confected non-problem. The supposed solution will just add more regulatory intrusion into the employer-employee relationship and even undercut the incentive for bosses to invest in their workers.

And the touted $4 billion benefit to the economy is basically an assumed number.

Any benefits would be offset by the unquantified costs of also allowing business to collude in striking one-size-fits-all pattern bargains. ‘We don’t want to compete on wages,’ says Tony Burke.

To the contrary, Australia’s high wage economy is unlikely to be sustainable unless business is allowed to escape its adversarial IR straitjacket and to incentivise its workforce to perform at high levels of productivity and flexibility

An engaged and productive workforce should be a source of competitive advantage in responding to changing market demand, technological disruption and a less collectivist and more diverse society.

Fair Work Ombudsman Anna Booth

Making the case for this requires some serious evidence-based research to highlight Anna Booth’s insider confession that the system is not designed to forge productive workplaces.

Sadly, it won’t come from the Productivity Commission. Nor from the Liberals unless they are provided with evidence on which to mount a politically compelling narrative.

For me, it’s been close to a professional lifetime since the unions blew up the Whitlam government, since Malcolm Fraser passed up the post-Whitlam opportunity, since Hawke and Keating quarantined the IR system from the neo-liberal reform agenda and since John Howard arguably lacked the preconditions to sell WorkChoices to the electorate.

At the Centre for Independent Studies, I’m keen to get some IR legal warriors together with some data-capable economists to make the case.

Michael Stutchbury is Executive Director at the Centre for Independent Studies. This was a speech to the HR Nicholls Society annual conference on 25 November 2025 in Melbourne.

Confessions of an Industrial Relations Club reporter