Executive Summary

At the centre of Australia’s mental health system lies a paradox. Government spending has soared, doubling and redoubling over the past three decades. Support programs such as the Better Access initiative and the National Disability Insurance Scheme have dramatically expanded access to therapy, medication, and support. Yet, for all this investment, the nation’s mental health has conspicuously failed to improve. Suicide rates have barely budged. Psychiatric drug use is at record levels. And each year, the number of Australians classified as mentally ill continues to rise.

Parts One and Two of this report document the scale of this expansion and its consequences. They show that rising expenditure has been accompanied by rapid growth in diagnosis, service use, and long-term dependency, without corresponding improvements in population wellbeing. The report argues that the problem lies not in a lack of commitment or compassion, but in the mental health system’s underlying design. We have built a system that produces patients rather than health. It medicalises distress, makes help dependent on diagnosis, and creates a bureaucracy that grows with each new case. Far from reliably reducing suffering, the system now appears, in some respects, to generate and entrench it.

The analogy with Repetitive Strain Injury (RSI), an Australian epidemic that peaked in the 1980s and then disappeared, provides a cautionary lesson. RSI was not caused by a virus, bacterium, or lesion, but by a convergence of cultural narratives, financial incentives, and institutional responses. When diagnosis became a pathway to validation and compensation, case numbers rose sharply. When those incentives changed, the epidemic faded.

A similar trend is now evident in mental health. Diagnostic categories like attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder have expanded significantly in recent decades. Some argue this indicates progress: improved diagnostic tools, greater awareness, and reduced stigma, which have helped reveal previously hidden suffering. Perhaps, but the proportion of people with psychoses, the most stigmatised conditions, has not risen substantially. The increase has been mainly in milder cases that enable access to accommodations, services, or financial support.

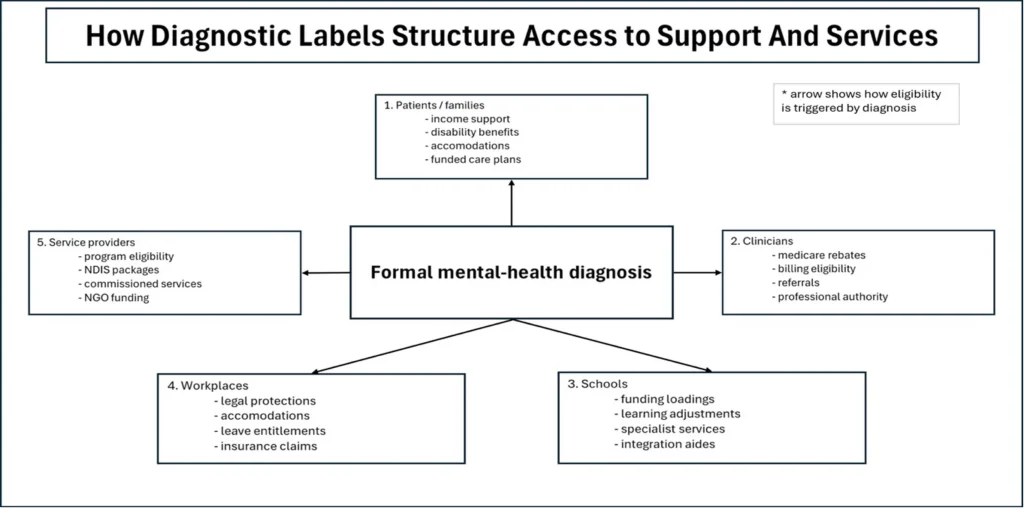

Distressed individuals seek diagnoses to access assistance; clinicians operate within funding frameworks that require them; schools, universities, and employers rely on them to justify special consideration; pharmaceutical companies profit from treatment; and governments respond with more programs, inquiries, and spending. Together, these various actors form a diagnostic-industrial-government complex: a self-reinforcing system in which each participant depends on diagnostic expansion to justify their role. As with RSI, the very act of naming a condition becomes a ticket into an expanding therapeutic system.

None of this implies that suffering is trivial or fabricated. Eating disorders can be fatal. Depression can destroy relationships and lead to self-harm. Severe psychotic disorders can require lifelong support. The issue is not whether people suffer, but whether medicalising their suffering has helped them to recover and live better lives. Judged by outcomes (recovery, prevention, and reduced chronicity), the system is falling short.

Part Three argues that reform has stalled because contemporary policy treats all distress as points on a continuum. The result is that distinct populations are conflated. One comprises people with severe, persistent psychological disturbances, such as psychotic disorders, profound autism, and treatment-resistant mood disorders. They require intensive, coordinated, and often lifelong professional care. But the system frequently fails them by forcing them to compete for resources with a much larger group of people who are experiencing milder difficulties. For many in this second group, long-term professional intervention risks converting temporary hardship into chronic dependency. In such cases, helping can become harmful.

The report proposes a different policy architecture, one that prioritises recovery as the norm, not the exception. It is built on five core reforms:

First, replace diagnosis-based eligibility with functional assessment. Support should be allocated based on what people can or cannot do, not on whether they meet the criteria for a psychosocial condition. Functional assessments should be conducted by independent assessors, repeated regularly, and coupled with time-limited support plans.

Second, adopt stepped care. Those with mild to moderate difficulties should receive low-intensity interventions first (counselling, peer support, digital tools) with a step-up to specialist care only if needed. As people recover, they step down. This reserves expensive, high-intensity services for those who genuinely require them.

Third, address contextual causes before medicalising them. Many difficulties labelled as psychosocial disorders are better addressed through the provision of decent housing, employment, and civic infrastructure than through clinical intervention.

Fourth, reward recovery, not retention. Clinicians and service providers should receive outcome-based payments for helping people return to work, education, or independent living, rather than fee-for-service payments that incentivise ongoing treatment. Success should be measured by how many people exit the system, not by how many enter it.

Fifth, collect data that measures what matters. Current reporting focuses on inputs, spending, and sessions delivered, rather than outcomes. A reformed system would track functional recovery, duration in care, and whether resources are reaching those with the greatest need.

These principles are not abstract. They are being tested now. In August 2025, the Australian Government announced Thriving Kids, a multibillion-dollar early intervention program for children with developmental concerns. How it is designed will reveal whether Australia is prepared to trial a genuine alternative—one that supports families without diagnostic labelling, expects developmental catch-up, and measures success by recovery, or whether it will become another pipeline channelling children into long-term therapeutic dependency.

The goal of reform is not to deny suffering or dismantle care, but to restore proportion and clarity to Australia’s response to psychosocial distress. A mental health system should be judged not by how many people it enrols, but by how many people no longer need it. A humane system does not shrink compassion; it sharpens it by distinguishing those who truly need lifelong care from those who need understanding, structure, and the opportunity to recover. Only by recognising when helping turns into harm can we build a system that genuinely promotes recovery, resilience, and human flourishing.

Introduction

Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets.

— Paul Batalden

In the 1980s, Australia experienced a medical phenomenon that baffled doctors and policymakers: an epidemic of Repetitive Strain Injury (RSI). Office workers, particularly those learning to use computer keyboards, reported chronic pain in their hands, necks, wrists, and arms. Thousands sought medical treatment, took extended sick leave, and received workers’ compensation for a condition that was largely absent in other countries.[1] Clinics specialising in RSI flourished, treatments were adopted with little or no scientific justification, and government agencies allocated significant resources to address what was widely viewed as a national health crisis.

At its peak, RSI was responsible for tens of thousands of compensation claims annually, resulting in total payouts of millions of dollars. Medical professionals debated its underlying causes, but no unique physiological marker distinguished RSI from other strains and discomforts. Working out at the gym, painting the lounge room or even writing letters longhand produced similar symptoms.

Almost as abruptly as it emerged, the epidemic faded away. It later became widely accepted that RSI was not a distinct medical disorder, but a syndrome produced by psychological and cultural factors.[2] The digital office environment introduced in the 1980s required workers to master unfamiliar skills, a source of stress for many. At the same time, economic incentives, such as generous workers’ compensation and paid sick leave, combined with sensational media coverage and heightened public awareness, led to a spike in cases. The very act of naming and diagnosing RSI granted it legitimacy, creating a feedback loop in which the syndrome became both medically and socially validated. In essence, the creation of the RSI diagnosis generated an epidemic in the absence of any detectable disease.

The RSI episode is not a template for understanding all illnesses, but it is an illustration of how diagnostic categories can expand rapidly when social expectations and institutional incentives align. This does not imply that those suffering from RSI were fabricating their pain; most genuinely experienced aches, stiffness, and discomfort. Some of these symptoms were, at least temporarily, debilitating. The essential question, however, is whether framing their problem as a medical disorder ultimately benefited RSI sufferers or whether it fostered dependency and prolonged disability.

RSI is long gone, but a similar phenomenon is unfolding in Australia today. The nation is said to be in the grip of a mental health crisis.[3] Of course, psychiatric disorders are not new. For centuries, profoundly distressed people have been committed to asylums and subjected to cruel and often useless treatments.[4] The diagnostic labels given to these individuals, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and others, are still used today. Although no precise cause for these disorders has yet been discovered, no one would be surprised to find they have a genetic or organic aetiology (or both).

These seriously afflicted people are not responsible for the current mental health crisis. Schizophrenia and bipolar disorders affect the same proportion of the population today as they did a century ago. Today’s mental health crisis results from a large influx of less severe disorders (binge eating, hoarding, and hundreds of others). These are commonly referred to as psychosocial disorders. To cope with the volume of new diagnoses, mental health funding has doubled and then doubled again, yet the number of people receiving psychosocial diagnoses continues to rise. It’s a paradox; the more money Australia spends on treating mental health, the worse our nation’s mental health seems to become.

Are we facing a genuine health crisis, or is the sharp increase in psychosocial disorders driven by the medicalisation of life’s problems and challenges? By diagnosing more people as mentally ill, are we genuinely helping them lead better lives, or are we sapping their self-reliance while shifting resources away from those with serious conditions who need them most?

This report seeks to answer these critical questions by examining the historical, economic, and health policies that have shaped Australia’s mental health landscape. It is not intended to diminish the suffering experienced by those diagnosed with a psychosocial condition. Rather, the issue at hand is whether Australia’s approach to mental health, one that increasingly categorises all forms of distress as medical disorders, alleviates suffering or exacerbates it by fostering a self-perpetuating cycle of diagnosis, treatment, and dependence.

The report is structured as follows: Part One highlights the scale of the mental health crisis, measured not only in dollars but also in broken lives. Part Two investigates the factors behind the rise in psychiatric diagnoses, and Part Three suggests policy reforms and strategies aimed at developing more effective ways to tackle the problems we currently label as psychosocial disorders.

Part One

The Paradoxical Economics of Mental Health: Rising Spending and Rising Diagnoses

When Brian Burdekin’s Human Rights and Mental Illness report was released in the early 1990s, it exposed a grim reality: tens of thousands of Australians diagnosed with severe psychiatric disorders were either homeless, in prison, or socially neglected.[5] The system, Burdekin argued, had failed those it was meant to protect. The response was swift. Governments pledged reform, and the National Mental Health Strategy (1992) set out a blueprint for change.[6] By the late 1990s, several mental health plans had been introduced, accompanied by significant funding increases aimed at shifting care from psychiatric institutions to community-based services.

In theory, this was a progressive step. The era of asylum-based care was ending, and modern treatments optimistically promised to permit people with psychiatric disorders to live with dignity in the community. However, a major structural flaw soon became evident. Profoundly disabled people, those who required considerable help to negotiate the demands of daily life, found themselves competing for support with people seeking care for a growing range of less severe conditions. Resources were stretched, and many severely incapacitated people were relegated to lonely, precarious, and often homeless lives. Something needed to be done, and Australian governments responded by commissioning further inquiries and vastly increasing expenditure.

A Tsunami of Inquiries and Spending

Since Burdekin’s report, Australia has seen a near-endless cycle of national inquiries, task forces, and commissions, including:

- Five National Mental Health Strategies and Plans (1993-2022)[7]

- Creation of a National Mental Health Commission and State Mental Health Commissions

- Productivity Commission’s Inquiry into Mental Health (2020)[8]

- Vision 2030 for Mental Health and Suicide Prevention (2021)[9]

- NDIS Review (2023)[10]

- Productivity Commission’s Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Agreement Review (2025)[11]

- Grattan Institute (2025). Bridging the gap — meeting the needs of Australians with psychosocial disability[12]

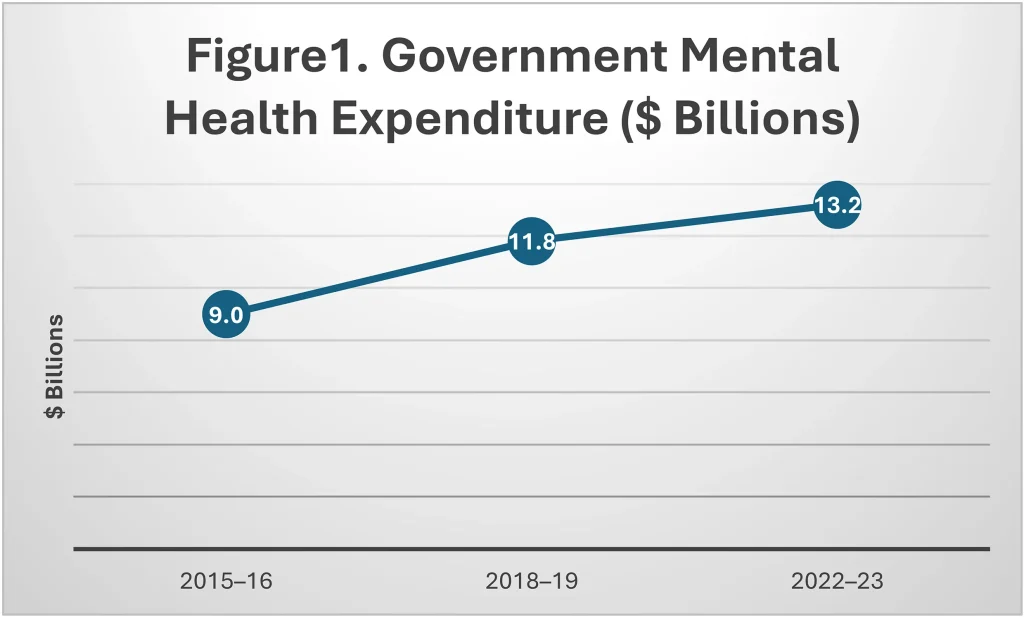

The numerous inquiries, committees and commissions that have examined mental health policy in Australia shared a common feature: almost without exception, they recommended increased funding, and governments obliged. Mental health expenditure rose by 65% from the 1990s to the early 2000s, but that growth was only the beginning.[13]

A major policy shift occurred with the introduction of the Better Access Initiative in 2006, which allowed Australians to claim Medicare rebates for psychological consultations and therapy.[14] The use of services expanded markedly. Using the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s (AIHW) constant-price expenditure data series, recurrent government spending on mental health services rose steadily over the following eight years, reaching around $8 billion in 2013–2014. In parallel, substantial additional costs were incurred through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) for medications commonly used to treat mental health conditions, including antidepressants, antipsychotics and stimulants.[15]

Despite the vastly increased spending in the first decades of the century, the demand for mental health services continued to rise. National Health Survey data show that by 2020–21, approximately 1 in 10 Australians reported using a mental health service in the previous 12 months.[16] Unsurprisingly, as eligibility and utilisation increased, overall expenditure continued to rise. According to AIHW’s constant-price estimates, total government spending on mental health services increased from $9 billion in 2013–14 to $13.2 billion in 2022–23, a rise of almost 50% in real terms in only seven years.[17] (See Figure 1.)

Mental health is now one of the largest areas of disease-specific health expenditure in Australia, comparable in scale to cardiovascular disease and exceeding expenditure attributed to cancer.[18]

Note. Expenditure figures are reported in constant prices but are not adjusted on a per-capita basis because mental health spending is driven more by diagnostic thresholds, eligibility rules, and care intensity than by population size alone. Population-adjusted figures show a similar trend and do not alter the conclusions.

Psychologists are the largest recipients of Medicare reimbursements for mental health services, but psychiatrists and general practitioners also receive substantial payments. The AIHW reports that, in the June quarter of 2024, nearly 3.4 million Medicare-subsidised mental health services were processed, equating to over 13 million per year.[19]

Although the bulk of mental health spending on clinical services comes from state and federal governments, some private health insurers also cover mental health treatment, and individuals often face out-of-pocket expenditures as well. There is no official accounting of the costs to businesses of missed days of work and the cost to schools for the extra accommodations made for those with psychosocial diagnoses. Still, these costs are substantial, and they grow with every new diagnosis.

Medications continue to add a considerable expense to the mental health budget. Eighteen per cent, almost one in five, Australians filled a prescription for a psychiatric drug in 2023, representing a 5% increase over the previous year.[20] Just imagine, the next time you fly, that, on average, at least one person in each row of the plane is taking a psychiatric medication.

Expenditure continues to rise.In 2023–24, publicly subsidised mental health medication provided through the PBS and the Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme cost $691 million.[21] Antipsychotic drugs (40%) and antidepressants (33%) are the most frequently prescribed psychiatric medications.

Total spending on mental health extends well beyond treatment to include long-term income and support entitlements. Since the rollout of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), expenditure on participants whose primary problem is classified as psychosocial disability has increased year on year, reaching $4.25 billion in 2023–24, a sharp rise from the early years of the scheme.[22] According to the Grattan Institute, the NDIS may have spent as much as $5.8 on psychosocial disability in 2025, a 37% increase in only two years.[23]

The inclusion of psychosocial conditions within the NDIS represents a major structural shift in the mental health system. Eligibility is tied to the presence of a formal diagnosis and evidence of permanent functional impairment, as defined administratively rather than clinically. This effectively transforms some mental health conditions into gateways to long-term financial and service entitlements. Average annual NDIS support packages for participants with psychosocial disability now exceed $70,000, reflecting the scheme’s focus on ongoing support rather than time-limited treatment.[24] While many NDIS clients have severe impairments that require substantial assistance with daily functioning, the scale and design of the scheme have raised concerns about cost growth, boundary definition, and the blurring of treatment, disability support, and income maintenance. One conclusion is impossible to avoid: the NDIS has become a significant driver of public expenditure related to mental health.

Increased Spending Has Not Improved Mental Health

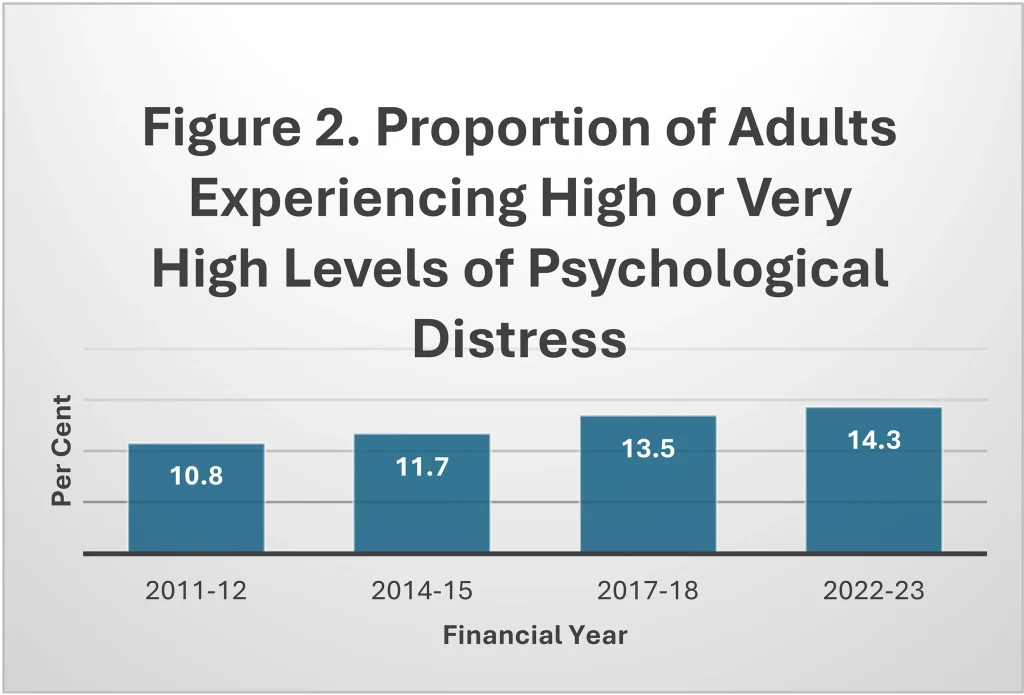

Despite rising rates of diagnosis, expanded treatment options, and sharply increased expenditure, mental health outcomes remain poor. The 2020–22 National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing found that 21.5% of Australians aged 16–85 experienced a psychosocial disorder in the previous 12 months, a proportion that has not declined over successive surveys despite substantial growth in funding for services and medications.[25] These observations are supported by the National Health Survey, which reports that the proportion of adults reporting high or very high psychological distress increased from around 11% in 2011-12 to almost 15% by 2022–23.[26] (See Figure 2.) While distress is influenced by factors beyond the health system, it seems clear that increased expenditure has not lowered distress among Australians. Indeed, it appears to be getting worse.

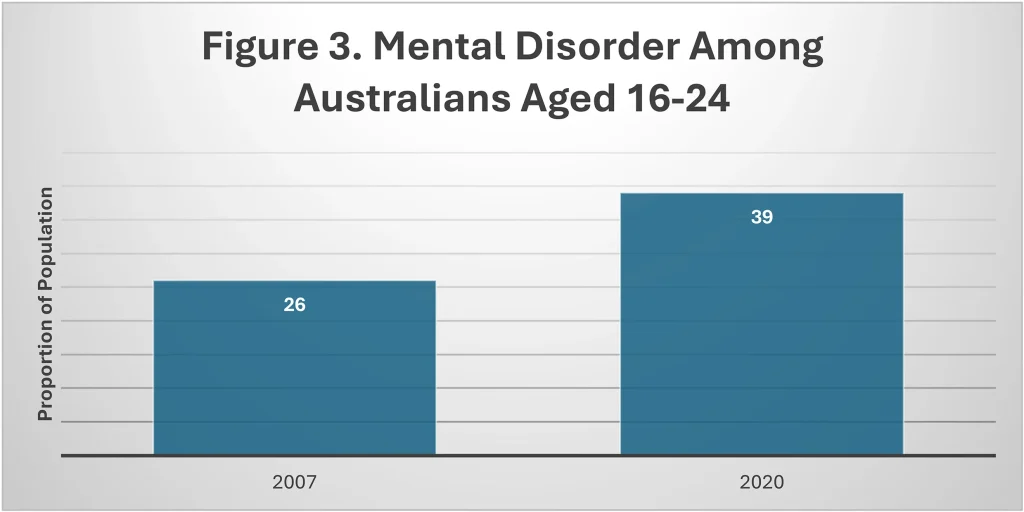

The lifetime prevalence of mental health diagnoses also remains very high: 42.9% of all Australians can expect to experience a mental disorder at some point in their lives.[27] Many of these disorders occur early in life. Among young people aged 16–24, the prevalence of diagnosed mental disorders increased from around 26% in 2007 to 39% in 2020–21.[28] (See Figure 3.)

Note. Proportion of Australians aged 16–24 meeting criteria for a mental disorder in the previous twelve months, 2007–2021. Estimates are drawn from the ABS National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Mental disorder refers to any diagnosable anxiety, mood, substance use, or behavioural disorder as defined by the ABS diagnostic criteria.

Severe outcomes tell a similar story. Suicide remains the leading cause of death among Australians aged 15–24.[29],[30] In 2023, record numbers of Australians were receiving the Disability Support Pension for psychological and psychiatric conditions, reflecting the growing scale and chronicity of mental ill-health within the working-age population.[31]

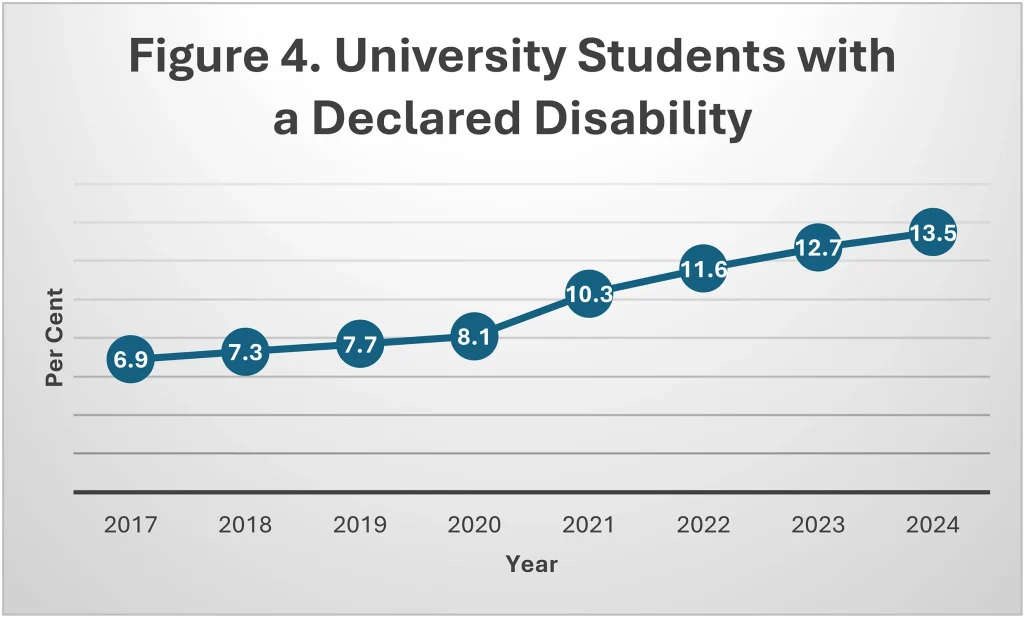

From 2011 to 2024, self-reported disability doubled among Australian university students. About half claim to be suffering from psychological problems.[32] (See Figure 4). Some of this growth reflects the institutional incentives created when diagnosis becomes the gateway to special exam consideration, longer times to complete assignments, and so on.

And Australia is not alone. Comparable trends are evident in the United States, the United Kingdom, and much of Europe, where rates of anxiety, depression, and self-harm, particularly among adolescents and young adults, have risen alongside expanded access to therapy and psychotropic medication.[33],[34] Over the past decade, the percentage of American university students who qualify for special consideration and examination accommodations due to disability has skyrocketed. At Harvard and Brown, it’s above 20%. At Stanford, it’s 38%. Like Australia, the increase has not occurred for physical disabilities, but in psychosocial conditions.

These figures reveal a troubling paradox: we are diagnosing and treating more people than ever before and spending record amounts on mental health care, yet the prevalence of psychosocial disorders continues to rise. In most areas of medicine, increased spending leads to advances in treatment that improve outcomes: longer cancer survival, better surgical outcomes and declining infection rates. Mental health care has proven to be an outlier in this respect. Many people who receive psychosocial diagnoses do not enter a path to recovery, but rather into a state of chronic service use, prolonged support plans, ongoing prescriptions, and repeated assessments. Instead of offering a way out, the system only offers a way in, a long corridor of bureaucratic processes designed to record symptoms, legitimise need, and allocate entitlements, but rarely to heal.

The lack of progress in combating psychosocial disorders raises uncomfortable questions. Where are all the new cases coming from? Have we simply become better at identifying previously overlooked cases, or are we expanding diagnostic criteria to encompass an ever-growing share of the population? Why do so few people recover? Are treatments ineffective? Part Two of this paper tries to answer these questions by explaining how mental health differs from other areas of medicine. Specifically, a psychosocial diagnosis no longer functions solely as a clinical tool for guiding treatment, but increasingly as an administrative threshold that determines access to long-term support, raising unavoidable questions about how diagnostic categories evolve and expand.

Part Two

Diagnosis Without Disease

In 1952, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) published the first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), a classification system used in many countries, including Australia. Homosexuality was included under ‘sociopathic personality disturbances’. This was not a metaphorical designation; it was a formal diagnosis, backed by the authority of the psychiatric profession. From that point forward, being gay was, officially, a mental illness.

Gradually, the social landscape began to shift. In the 1960s and early 70s, the gay rights movement gained strength. Activists protested at APA meetings, disrupted medical school lectures, and lobbied for change. In 1973, at the APA’s annual meeting, members were asked to vote on whether homosexuality should remain a mental disorder. A majority voted to remove it from the DSM. From that moment, being gay was no longer a mental disorder.[35]

The history of the homosexuality diagnosis illustrates a central truth about psychosocial diagnoses: they are nothing like illnesses in the usual sense. No one debates whether diabetes is a disease. There are no campaigns to reclassify malaria or tuberculosis, and no one needs to lobby for the medical recognition of kidney failure. In most areas of medicine, diagnoses are based on objective evidence, things that can be observed, measured, or verified through blood tests, biopsies, or physical examinations.

Psychiatry is different. Despite nearly a century of research, no objective cause has been identified for any psychosocial disorder.[36] Yet we continue to treat them as if they were equivalent to medical illnesses, as though anxiety or borderline personality disorder were the mental counterparts of pneumonia or cancer. This analogy is not only flawed; it is fundamentally misleading. When a doctor diagnoses pneumonia, the word usually points to an identifiable disease process: infection of the lungs by bacteria or a virus.[37] When a psychiatrist diagnoses depression, by contrast, the word points to a cluster of feelings and behaviours, sadness, loss of interest, poor concentration, insomnia, but not to an identifiable cause. This difference matters. Pneumonia explains why you have a cough. Depression does not explain why you are sad; it simply restates the fact in clinical language. To say one’s sadness is caused by depression is circular reasoning because the depression label is derived from the sadness it is supposed to explain. It is equivalent to saying a person is sad because the person is sad.

This does not mean sadness, loss of interest, poor concentration, and insomnia are trivial or unimportant. Far from it. But it does mean we must be precise about what DSM diagnoses are, and what they are not. They describe problematic behaviours, not underlying causes. To its credit, the American Psychiatric Association has acknowledged the descriptive nature of psychiatric diagnoses. Its website once included the following disclaimer:

Diagnostic criteria provide a common language for clinical communication… Patients sharing the same diagnostic label do not necessarily have disturbances that share the same aetiology, nor would they necessarily respond to the same treatment.[38]

Unfortunately, this caution is largely overlooked. Clinicians and pharmaceutical companies routinely promote the idea that DSM diagnoses are illnesses, much like diabetes, which come with a standard treatment protocol, often including specific drugs. Youngsters diagnosed with ADHD are commonly prescribed stimulants; a depression diagnosis may elicit a prescription for antidepressant medication.

Some clinicians go even further, asserting biological causes for DSM diagnoses with little definitive evidence. For instance, some clinicians claim that depression results from a ‘chemical imbalance’ in the brain, an imbalance that is supposedly rebalanced by antidepressants. This idea is more of a conjecture than a fact. Despite numerous attempts, no consistent abnormality in brain chemistry or neurological functioning has been identified among individuals diagnosed with depression.[39]

The illusion that psychiatric diagnoses are medical illnesses is often reinforced by the widespread use of medical-sounding but scientifically empty language. A striking example is the term ‘neurodiversity’. It was coined by the Australian sociologist, Judy Singer, who candidly explained that she invented it because ‘Neurodiversity sounds really important and it will legitimise our claims to be taken seriously’.[40]

The medicalisation of psychological problems and the use of vague terms such as neurodiversity obscure the true origin of many, perhaps most, psychosocial disorders. As demonstrated in the homosexuality example, these disorders are not grounded in neurology, germs or brain chemistry, but in behaviour, values, and social norms. Without the need to show evidence of disease, any troubling behaviour can be turned into a pathology simply by inventing a new diagnosis or by stretching the boundaries of an old one. As discussed next, the proliferation of new categories and the steady broadening of old ones is indeed a major driver of our current mental health crisis.

The Expansion of the DSM: From Modesty to Maximalism

When the first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-I) appeared in 1952, it was a modest publication: just over 100 loosely defined conditions spread across 130 pages. Designed primarily for hospital statistics and institutional planning, it offered little more than a rudimentary taxonomy of symptoms and syndromes and did not claim any scientific status. The DSM-II added 82 more conditions, but made no greater claim to precision. A big change occurred with the publication of DSM-III in 1980, a watershed moment in modern psychiatry. For the first time, the manual introduced explicit diagnostic criteria, an ambitious classification system, and the promise of diagnostic reliability. It was heralded as a revolution in psychiatric language. But it also initiated a new trend: diagnostic inflation.

Each subsequent edition of the DSM added new disorders, subdivided existing ones, and often lowered the threshold of pathology required for diagnosis. By the time DSM-IV was published in 1994, the list had grown to 297 disorders. DSM-5, released in 2013 and updated in 2022 (DSM-5-TR), brought the total to more than 300.

Among the newer entries are:

• Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (chronically irritable children)

• Binge Eating Disorder (formerly a subcategory)

• Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder

• Mild Neurocognitive Disorder (a category of ‘pre-dementia’)

• Hoarding Disorder

• Internet Gaming Disorder (included provisionally for further study)

• Prolonged Grief Disorder

The list raises difficult questions about where normal human variation ends and pathology begins. Hoarding? Internet gaming? Even grief, once considered a universal and understandable response to loss, is now classed as a potential disorder under certain conditions. Traits that were once considered personality differences, such as social reticence in children or distractibility in adults, may now meet criteria for autism spectrum disorder or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Because physical signs are unnecessary for a psychosocial diagnosis, any human behaviour can become pathological. Here’s how the system works. A clinician proposes a new diagnosis. Expert working groups then review the literature, solicit opinions, and conduct field trials to assess whether psychiatrists will accept the proposal. If enough psychiatrists are supportive, the new diagnosis is incorporated into the DSM, and a new condition is created.

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD), published by the World Health Organisation, offers a similar taxonomy developed using comparable methods. Although the categories differ slightly, the overall outcome remains the same: behavioural patterns are classified into disorders, not based on lab results but through expert consensus. There is no limit to the number of psychiatric conditions that can be generated.

Once a condition is included in the DSM or ICD, it takes on a life of its own. It acquires medical and cultural legitimacy. Treatment protocols are developed, drugs are approved, clinics are established, and advocacy organisations emerge. A diagnosis becomes more than a clinical label: it becomes a social identity, a passport to entitlements, and a gateway to special treatment. Unsurprisingly, given the benefits that flow from diagnosis, both the number of recognised disorders and the number of people identified as patients have grown steadily.

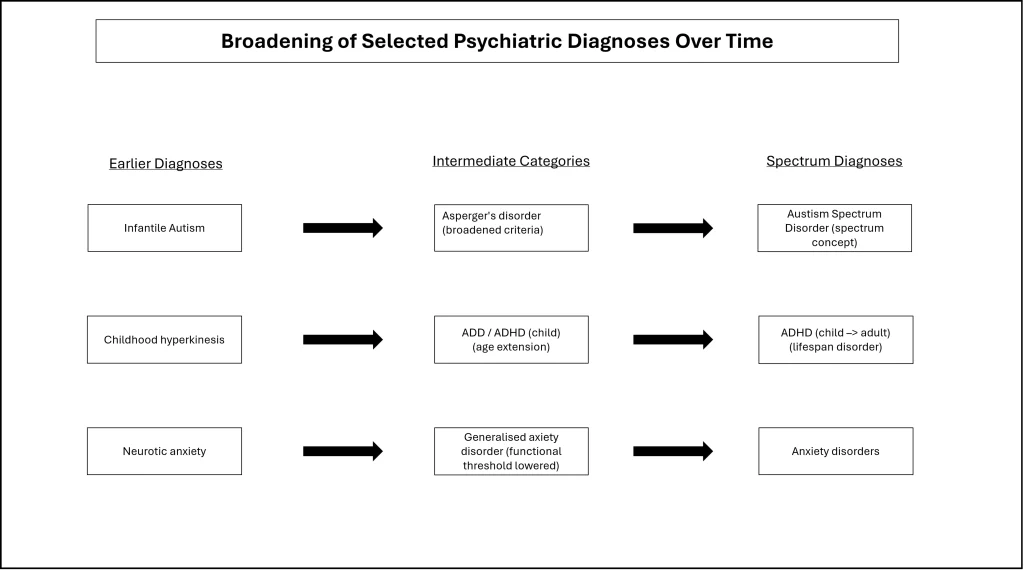

Besides creating new disorders, the diagnostic criteria for older ones are constantly being expanded. Autism is a perfect example. In the 1960s, autism was narrowly defined and thought to be very rare. The diagnosis required symptom onset before age 3, with grave cognitive, social, and behavioural difficulties. In 1994, the DSM-IV introduced a new diagnosis, Asperger’s syndrome, which was milder and more common. This led to a significant increase in diagnoses. In 2013, the DSM-5 merged Asperger’s into an even broader autism spectrum disorder (ASD), further expanding eligibility.

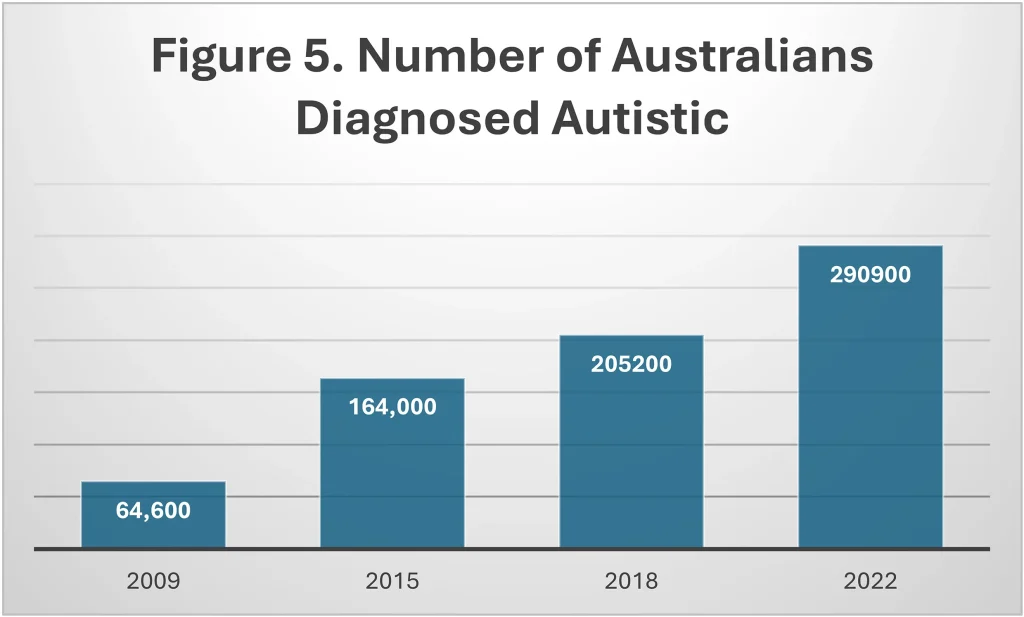

As a result, children with profound impairments, non-verbal, highly distressed, and requiring constant supervision, now share a diagnosis with children who would once have been described as socially awkward or shy. Between 2009 and 2022, the number of Australians diagnosed with autism increased by 350%.[41] (See Figure 5.) At the same time, a substantial institutional infrastructure developed around ASD, including support groups, advocacy organisations, and specialised educational settings. These bodies often resist distinctions of severity, with the unintended consequence that individuals with the most severe impairments must compete for resources with those whose functional difficulties are far less pronounced.

Allen Frances, the psychiatrist who led the development of the DSM-IV, has expressed serious concerns about the role he played in the creation of ASD, which he believes contributed to the explosion in diagnoses.[42] Frances acknowledges that reduced social stigma and greater awareness may be responsible for some of the increase in diagnoses. However, he argues that most of the growth comes from making the criteria exceedingly broad, thereby capturing children whose difficulties would not have been considered pathological in previous eras. This distinction matters: Frances is not denying that autism exists or that some children were previously underdiagnosed; he is questioning whether the current diagnostic boundaries appropriately distinguish disorder from normal developmental variations or from other conditions. For example, intellectual disability diagnoses have dropped in recent years because many who would formerly have received that diagnosis are now called autistic.[43]

Frances laments that socially awkward behaviour, such as bashfulness, once rather endearing, has been turned into an illness. As a side effect, the rapid growth in autism has provided ample material for conspiracy theories that seek to link autism to vaccines, environmental toxins, and painkillers used in pregnancy, and food additives.[44]

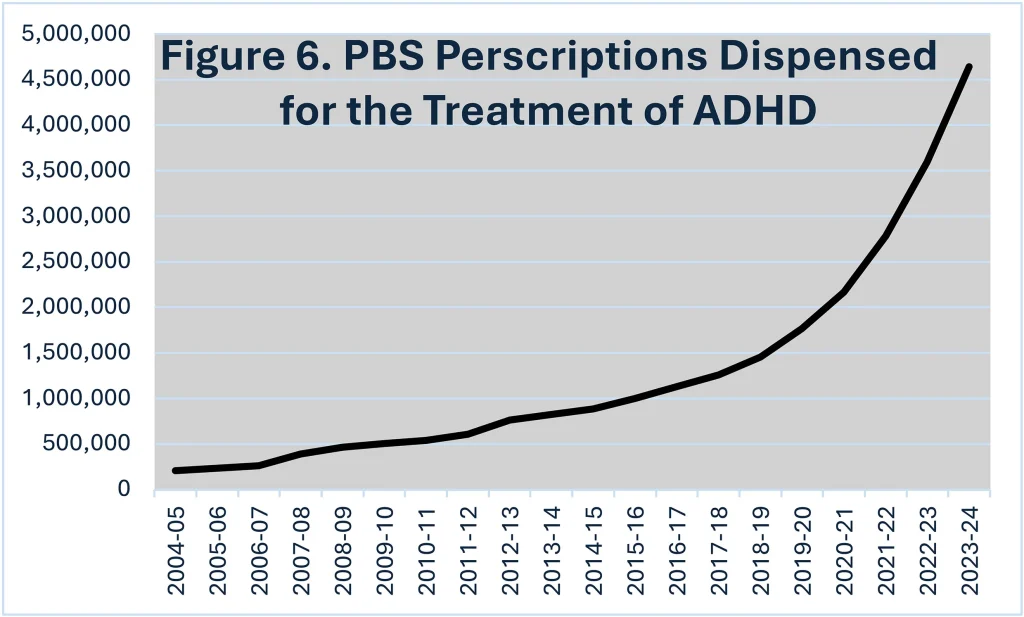

ADHD has followed a similar rapid growth path. The annual number of stimulant prescriptions for ADHD increased from around 1.2 million prescriptions in 2004–05 to over 4.5 million in 2023–24 (see Figure 6). While the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria require ADHD behaviours (inattention, hyperactivity) to be present before age 12, the past two decades have seen a sharp rise in adults receiving an ADHD label and medication.[45] This increase is too big to be attributed solely to population growth. It mainly reflects increased prescribing from general practitioners and an increasing tendency on the part of adults to seek access to stimulant drugs for their ‘ADHD’.[46]

Note. Total number of stimulant prescriptions for ADHD dispensed under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, 2004–05 to 2023–24.

Anxiety disorders exhibit the same expansionary dynamic in a less visible but more pervasive form. Diagnostic thresholds have gradually widened, and anxiety has increasingly been conceptualised as a spectrum condition rather than a response to specific stressors or circumstances. Large proportions of the population now meet the criteria for an anxiety disorder at some point in their lives. Unlike autism or ADHD, anxiety diagnoses are less tightly linked to a single institutional gateway, but they permeate primary care, education, workplaces, and pharmaceutical prescribing, contributing substantially to overall diagnostic load. Figure 7 depicts in schematic form how diagnoses expand over time.

Anxiety, autism and ADHD are leading the way, but diagnostic expansion has not been confined to a single condition. Growth has occurred across multiple domains simultaneously. As already noted, all that is required to create a new disorder, or to broaden an existing one, is professional agreement. Such an agreement is rarely difficult to achieve when institutional incentives are aligned. These incentives, financial, bureaucratic, and political, are examined next.

Figure 7.

Who Benefits from Diagnoses?

As noted, the number of recognised mental conditions continues to grow with each new edition of the DSM or ICD. This expansion is fuelled by a complex web of incentives (see Figure 8). For the person seeking help, the clinician making the diagnosis, the institution providing care, and the government or insurer funding the service, the value of a diagnosis lies in the opportunities it unlocks:

Parents: Without a diagnosis, there is little that can be done for a child struggling in a mainstream classroom. But if the child is diagnosed with ADHD or autism, new avenues open: a tutor, an individualised learning plan, and extra time on exams. Given the benefits, it’s not surprising that parents pursue a formal diagnosis. Nor is it surprising that providing diagnoses has become a lucrative business. Some psychologists display signs outside their clinic entrance offering ADHD and autism diagnoses for a fee.

Universities: In higher education, a psychosocial diagnosis can attract ‘bonus points’ for university admission. Once enrolled, a diagnosis may also bring special accommodations for assignments and exams (extra time, for example).

Workplaces: In the workplace, a diagnosis can justify special leave entitlements, shield an employee from performance targets, and activate legal protections.

Individuals and families: Under the NDIS, a diagnosis may unlock direct financial support, often substantial and indefinite.

Clinicians: In Australia, a formal diagnosis is required for billing. Psychologists cannot claim a Medicare rebate for ‘relationship stress’ or ‘existential despair’, but they can for generalised anxiety disorder or adjustment disorder. Diagnoses have become a bureaucratic currency, needed to justify treatment and unlock funding.

Teachers and school psychologists: If a student is disruptive, distracted, or falling behind, the path to help runs through a formal diagnosis. Label the child on the autism spectrum or ADHD, and the school becomes eligible for support funding. Without a label, both student and teacher are left to struggle.

Health providers: At the system level, diagnosis is the organising principle. Hospitals, schools, insurers, and welfare agencies all operate on coded diagnostic categories. A condition must be named to be authorised, funded, and measured.

Health industries: Diagnostic labels drive research grants, shape scientific careers, and determine drug approvals. Pharmaceutical companies require diagnoses to justify their products. Entire industries, from telehealth startups to mental health apps, depend on telling people what’s ‘wrong’ with them.

Policymakers: Mental health funding is often tied to prevalence rates, which rise as definitions broaden and awareness campaigns multiply. Politicians are unlikely to question these trends, fearing accusations of insensitivity or neglect. It is easier to promise more services, more programs, and more access, especially for newly recognised or marginalised groups.

Figure 8.

Everyone in the system gains something from diagnosis. The patient receives treatment and, in many cases, government-funded financial support. The clinician gets a billable condition. The drug company makes a sale. The school receives additional resources. The student gains extra examination time. The researcher gets a grant. The politician wins re-election. The system expands. The only thing not guaranteed is whether anyone actually recovers.

Awareness and Stigma

Before concluding that the incentive structures outlined above are the leading cause of increased diagnoses, it is worth examining the claim, common among mental health professionals, that the rise in psychosocial diagnoses results from greater awareness of psychosocial disorders and a reduction in the stigma once associated with them. There is certainly evidence for this in the literature.[47] For individuals who previously suffered in silence, enduring profound distress without understanding or support, a greater awareness of psychosocial disorders has brought them into the mental health system. The critical question, however, is not whether some people are suffering from psychosocial issues, they clearly are, but whether the explosive growth in diagnoses demonstrates a mental health crisis or a widening of diagnostic boundaries. The evidence favours the latter. Specifically:

Differential growth by disorder type. If awareness and the removal of stigma were the primary drivers of diagnostic growth, we would expect proportional increases across all disorders as people became more comfortable seeking help. Instead, psychotic diagnoses (the most stigmatised) show stable prevalence while anxiety, autism, and ADHD surge dramatically. This pattern is more consistent with diagnostic boundary expansion than with improved case-finding of pre-existing conditions.

Continued acceleration without plateau. Awareness campaigns have been going on for over 15 years. If they were primarily uncovering previously hidden cases, rates should have plateaued once most of the undiagnosed cases were identified. Instead, autism, ADHD, and other conditions continue to expand at a rapid rate. This persistent upward trajectory suggests not the discovery of hidden cases but the continuous expansion of what counts as pathological.

Treatment without recovery. Perhaps most troubling, the massive expansion in diagnosis and treatment has not been accompanied by corresponding improvements in population mental health. Despite unprecedented access to mental health services, psychosocial distress among Australians continues to rise. This suggests that medicalisation may be addressing suffering in ways that provide validation without enabling people to develop the capabilities, relationships, and life circumstances that promote genuine wellbeing.

Age and demographic patterns. The increases in prevalence are heavily concentrated among young people and in mild-to-moderate cases. The expansion is occurring precisely where diagnostic boundaries are most ambiguous and where institutional incentives are strongest, in schools seeking funding, among university students seeking accommodations, and in populations eligible for NDIS support. This pattern raises questions about whether awareness campaigns are helping people access genuinely therapeutic interventions, or whether they are inadvertently teaching people to frame ordinary developmental struggles as pathological conditions requiring professional intervention.

Substitution effects. As noted earlier, intellectual disability diagnoses dropped as autism diagnoses increased; this suggests reclassification rather than improved case-finding. Similarly, many children who would once have been considered shy, energetic, or distracted now receive autism or ADHD diagnoses. This represents not the discovery of previously invisible conditions, but a shift in how we interpret and respond to human variation.

The most parsimonious explanation is that awareness and stigma reduction campaigns may have reduced the reluctance to seek mental health services, but this achievement has occurred within a system structurally oriented toward medicalisation. Awareness campaigns have successfully normalised the idea that psychological struggles indicate illness requiring professional treatment. They have not, however, demonstrated that medical framing and intervention represent the most humane or effective response to the suffering they’ve helped make visible.

This creates a genuinely difficult situation. The suffering revealed by awareness campaigns is real. A teenager experiencing debilitating anxiety or a family struggling to understand their child’s social difficulties both deserve support and understanding. The question is not whether to help, but how. Medicalisation offers one pathway: diagnosis, treatment, and professional intervention, but it forecloses others. It displaces responses that are relational (friendship, family, community), educational (learning skills, developing capabilities), social (addressing loneliness, inequality, purpose), or spiritual (finding meaning, accepting limitation).

Critics of medicalisation are not dismissing suffering or advocating neglect. Rather, they argue that framing all distress as illness may paradoxically prevent people from accessing the very resources most likely to enable them to lead good lives. When ordinary struggles become symptoms, when shyness becomes a spectrum disorder, when grief becomes pathology, we risk teaching people that their difficulties are beyond their control, that all life’s challenges require professional expertise, and that the goal is symptom reduction rather than the development of character, capability, and connection. Our mental health system should be designed to help people flourish rather than merely teach them to identify as ill. Diagnoses, as discussed next, are not benign.

Diagnoses are not Benign

The expansion of diagnosis has had mixed effects. For some people, particularly those with severe difficulties who were previously dismissed or misunderstood, diagnostic recognition has opened doors to essential support. For others, particularly those with mild difficulties that might once have been considered within normal variation, diagnosis has brought questionable benefits alongside real harm. They have reshaped how people perceive themselves. Unlike many medical conditions, psychosocial diagnoses are not just temporary classifications; they can become permanent identities. Worse still, medicalisation has displaced other, more humane, responses, those that are relational, educational, social, or spiritual. When all distress is treated as disease, we risk abandoning the ordinary resources of life: friendship, family, work, and responsibility.

Diagnoses can have profound effects on a person’s sense of self, especially in childhood and adolescence, a critical time for identity development. Receiving a diagnosis can change how young people view themselves and how others view them, reinforcing the ‘sick’ role and stigmatising future social interactions.[48] Adolescents struggling to grow up learn to blame their ‘disorder’ for any difficulties. They become reliant on therapists and counsellors and lose any sense of agency. Minor setbacks can send them reeling.[49]

The formation of advocacy groups and communities around specific diagnoses, such as autism, provides support and solidarity, but can also become echo chambers that resist changes to diagnostic criteria, as these identities become integral to their self-understanding.[50] When a diagnosis becomes part of one’s identity, recovery may feel like a betrayal of those left behind.[51]

None of this suggests that large numbers of people are faking illness for gain. Much of the suffering is all too real. Eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa can be fatal. The behaviours diagnosed as depression can unravel relationships and lead to self-harm. Autism, in its severe forms, may require lifelong care. ADHD can derail education. People diagnosed with schizophrenia might require daily support. These are not trivial problems. The question is not whether people suffer, but whether medicalising their suffering has helped them to lead better lives. If the ultimate test of a mental health system is whether people get better and new cases are prevented, then we must face a hard truth. For all its scale, sincerity, and cost, our system is failing at the very thing it claims to do.

The problem is that the mental health system does not merely respond to distress; it helps generate, frame, and entrench it. Through a set of incentives, the system rewards diagnostic labelling and reinforces the belief that if someone is struggling, they must be ill. The final part of this paper presents an alternative approach: a system based on need, rather than diagnosis. This is not to dismiss the genuine progress that awareness campaigns have achieved in helping some people access needed support. Rather, it recognises that a system designed primarily around diagnostic categories, whatever its original intentions, inevitably creates incentives for diagnostic expansion that can undermine its stated therapeutic goals. It robs people of agency and medicalises all life experiences. What is required is a system that aims not to label people, but to help them overcome problems without adopting the identity of being ill.

Part 3

A Better Way to Help

Australia’s mental health system is not short of money, compassion, or good intentions. It’s short of performance. Billions of dollars flow through a labyrinth of programs, from Medicare-funded therapy sessions to the NDIS, and a variety of clinicians and organisations. Yet outcomes have stagnated. Suicide rates remain high. Emergency departments are overwhelmed. And each year, more Australians are diagnosed with psychosocial disabilities than the year before.

Part One showed the paradox: as spending has risen, population mental health has not improved. Part Two explained why. Diagnostic expansion has progressively reclassified ordinary human variation and adversity as pathology. The DSM has grown from 106 conditions to more than 300. Shyness became social anxiety disorder; prolonged grief became a disorder; and ADHD has spread from children to adults.

This expansion is not accidental. It is sustained by a variety of incentives. Clinicians gain billable diagnoses; families unlock services and educational accommodations; schools and universities trigger additional funding; pharmaceutical companies expand markets; advocacy organisations grow their membership; and governments appear compassionate and responsive. The one outcome that is not systematically rewarded is recovery. The system we have built produces patients rather than health. It medicalises normal experience, crowds out families and communities with professional services, and measures success by service utilisation rather than by people resuming ordinary lives. After decades of expansion, it is time to accept that this approach has failed. The system produces patients rather than health. Part Three seeks to provide a better way to help.

Problems with the Current Policy Consensus

As the demand for mental health services increases, governments respond by funding more clinicians, more programs, more diagnostic pathways, and more access. This is in line with the recommendation of every major policy review of the past two decades, including the Productivity Commission’s 2020 Mental Health Inquiry,[52] the NDIS Review,[53] and the Grattan Institute’s Bridging the Gap.[54] These reports deserve to be taken seriously. They are empirically grounded, institutionally informed, and motivated by genuine concern for the population’s mental health.

The Grattan Institute report is particularly pertinent. Based on statistical modelling, the Institute estimates that 130,000 working-age Australians with significant psychosocial disability receive no formal support and proposes a new National Psychosocial Disability Program funded largely by redirecting expenditure from the NDIS. The report pays particular attention to service delivery: better coordination, smoother pathways, clearer governance, and fewer gaps. It argues that Australia should meet the needs of those who are not currently receiving care by creating a new, nationally coordinated tier of services, regionally commissioned, and managed through layered oversight structures—a National Commissioning Authority, State Commissioning Boards, consortia, and performance frameworks.

There is a logic to these proposals, but it’s far from certain that additional layers of bureaucracy will improve outcomes. The UK National Health Service has repeatedly reorganised its commissioning architecture in pursuit of efficiency, integration and accountability. The result has been rising administrative overhead, increasingly risk-averse management, heavy compliance burdens for clinicians and providers, and a persistent failure to provide timely access to care.[55]

Australia’s NDIS shows similar dynamics. Participants and providers now spend large amounts of time assembling evidence, navigating access processes, attending planning meetings, managing reporting requirements and preparing for reviews. Administrative activity proliferates while recovery and functional improvement are difficult to identify.[56]

The problem is that complex service systems develop their own internal logic and their own constituencies. Once created, commissioning bodies, governance frameworks and compliance structures are rarely dismantled, even when they fail to deliver the outcomes for which they were established. Extending the commissioning model risks reproducing the problems that characterise both the NHS and the NDIS: rising administrative intensity, diluted accountability for outcomes, and a growing distance between institutional activity and the lives of people in distress. The caution here is not that coordination and governance are unimportant. It is that complexity, once institutionalised, becomes self-protecting, and bureaucratic expansion is a poor substitute for clarity about who truly needs intensive professional care, and who does not.

In addition to a new delivery framework, the Grattan Institute report recommends replacing diagnosis-based eligibility for care with functional assessment, emphasising recovery-oriented services, and providing time-limited interventions. These are serious, well-intentioned proposals that deserve support. However, on their own, they are unlikely to stem the growth in psychosocial disorders. The problem lies in Grattan’s diagnosis of the underlying issue.

Extending and refining the mental health system is not the solution to Australia’s mental health crisis; it is the problem. Extending it risks compounding the very harms we seek to reduce. Rather than creating new bureaucracies in the hope of improving efficiency, we need a fundamentally different system; one that recognises the risk of therapeutic harm. That is, when professional intervention converts temporary hardship into chronic dependency, helping becomes harmful. The remainder of Part Three explains why and sets out the steps required to create a rational and humane approach to mental health.

Not all Distress is a Disorder

Modern mental health policy rests on the idea of a continuum; disorders ranging from psychosis to exam stress are viewed as branches of the same tree. This is morally incoherent. A person with schizophrenia who is hallucinating and has withdrawn from society requires professional services, crisis response, stable housing, and sustained support. A stressed university student needs a coffee break, a friend, and perhaps a mindfulness app. Yet both are swept into the same category, psychosocial disorder, and they compete for services from the same funding pool. This is compassion without proportion — a desire to help everyone that leaves the most vulnerable underserved.

Treating all forms of distress as points on the same spectrum has predictable consequences. The mildly afflicted overwhelm services designed for the seriously impaired. Professional attention flows towards those who can articulate need, complete assessments, and navigate systems, not toward those who are most in need. According to the Productivity Commission’s Mental Health Inquiry,[57] roughly half of all Medicare-subsidised psychological and psychiatric services go to people with mild or moderate symptoms, while people with severe, enduring problems often receive fragmented care or none at all.

The first step in creating a fair and effective mental health system is to differentiate serious psychological disturbances requiring support and long-term care from difficulties of living — grief, loneliness, unemployment, insecure housing, academic failure, workplace stress, family breakdown, and the turbulence of adolescence. These difficulties can be painful, sometimes acutely so. But they are not pathologies; they are responses to circumstances, and they demand different solutions.

To ensure that resources flow to those who most need them, a rational mental health system must begin with triage by severity and persistence:

Severe conditions such as psychoses, bipolar disorder, and profound autism require continuous, intensive specialist-led care, including medication, crisis response, housing, and supported employment.

Moderate, episodic conditions such as depression and anxiety should be managed outside the mental health system in community settings or with time-limited clinical interventions.

Problems arising from life circumstances such as grief, financial stress, and relationship breakdown should be addressed entirely outside the mental health system, through civic networks, workplaces, and schools.

The same principle applies within diagnostic categories. For example, The Lancet Commission on the Future of Care and Clinical Research in Autism proposed dividing autism into two broad groups: profound autism, which includes individuals with significant intellectual or language impairments requiring lifelong support, and ‘other forms of autism’, which covers a wide range of abilities and adaptive potential.[58] The intention, the Commission explained, ‘is not to stigmatise but to ensure equity’. When all autism is treated as equal, scarce resources are spread thinly, leaving the most disabled without adequate help. In Australia, this problem is especially acute: the NDIS allocates more than a third of its total budget to autism, but much of it goes to children who will almost certainly function independently as adults, while those with profound disabilities remain under-supported. Funding should be allocated to those most in need, and annual audit reports should disclose the proportion of funds directed to severe versus mild conditions.

Attempts to distinguish between profound and mild autism may provoke opposition from some advocacy groups. They argue that autism and some other developmental conditions are merely ‘different ways of being’, not disabilities. Those who wish to adopt an autistic identity are certainly entitled to do so. A problem arises, however, when their rhetoric dominates public debate and funding, eclipsing those who cannot speak or live independently, and whose families bear lifelong caring burdens.[59] If advocates insist that people diagnosed as autistic are thriving in their alternate identities, then logically, they should not require public subsidies.

Allocate Assistance According to Need Rather Than Diagnosis

At present, the gateway to support is a diagnosis. Those seeking help must first obtain a clinical diagnosis of autism, ADHD, anxiety disorder, or some other diagnosis. Clinicians are paid to provide these labels. The result is a diagnostic economy in which entitlements are earned by having a diagnosis. A needs-based system would reverse this logic. It would focus on what forms of assistance are required to enable people to live better lives, not on diagnostic labels.

This principle already underpins physical disability services, where eligibility is based on mobility, self-care, and communication needs, not on the name of a disability. The same principle should be applied to mental health. A reformed mental health system would offer high-intensity services for those with severe, enduring problems. Support for situational distress should be delivered outside the system through school counsellors, parenting programs, and peer-led groups.

A needs-based approach is consistent with recommendations in the Grattan Institute report and reflects successful international models, such as the Stepped Care Framework adopted in the UK’s Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) program.[60] As already noted, the NHS has its administrative difficulties, but the IAPT is one of its success stories. Those with mild to moderate problems are offered low-intensity treatments. This may include counselling, smartphone apps, or computerised behavioural therapy. Help adapts as a person’s needs change. If there is little improvement, individuals are stepped up to more intensive treatment. As they recover, they step down to lower levels of care. This approach uses resources effectively by reserving expensive, high-intensity treatments for those who genuinely require them. The same logic should apply to all disorders. Where possible, the goal should always be recovery, not dependency.

Focus on Recovery Rather than Dependency

Everyone in the disability sector is aware of how incentives can become a trap that works against rehabilitation. The Australian Disability Support Pension (DSP) and the NDIS were specifically designed to minimise the perverse incentives that may keep people sick. Those receiving benefits are regularly monitored to assess whether they continue to require care, and various support services are provided to help them return to work. Under current NDIS rules, those who return to work are not immediately penalised by loss of benefits. This system works, in theory, at least, for disabilities stemming from birth, acquired illnesses, and injuries incurred in car accidents, sports, and workplace mishaps.

When it comes to mental health, however, the disability support system often fails, because psychosocial conditions differ from other forms of disability in three distinct ways.

Measurement. The healing of a broken leg can be assessed through imaging and weight-bearing tests, permitting clinicians to monitor improvement objectively. No equivalent tools exist for psychosocial problems, which rely on self-report, which is subjective and difficult to confirm.

Course and predictability. Recovery from a fracture follows a predictable course with achievable goals and measurable milestones. Psychosocial conditions are episodic and relapse-prone. Without time-limited, goal-focused treatment plans, psychological care can easily become indefinite maintenance rather than targeted recovery.

Patient identity. When access to support hinges on being unwell, remaining unwell is entirely rational. Diagnosis-based payments create a strong incentive to avoid improvement. Unlike work injuries, psychosocial conditions can become a permanent identity, making recovery seem naïve or even insulting. Advocacy groups amplify this permanence narrative, lobbying for indefinite support rather than structured recovery strategies.

These differences mean that a reformed mental health system must learn to treat recovery as the norm, not the exception. As the Grattan Institute report recommends, dealing with these problems and reversing the incentive trap must start by replacing diagnoses with functional assessments. Eligibility for support should be based on what people can do and what help they need, not on whether they meet DSM criteria for a condition. Functional assessments should be conducted by independent assessors and repeated regularly, and all support should be time-limited. Anyone deemed capable of independent living should gradually transition off benefits.

The current mental health system rewards diagnosis. Clinicians are paid for assessments that generate labels. Patients and their families gain access to services by acquiring those labels. Advocacy groups expand their influence by increasing the prevalence of their diagnosis. Governments, fearing voter backlash, respond with more funding, which fuels the next cycle of growth.

What is needed is a fundamental dismantling of the diagnostic-industrial-government complex that sustains the illusion of an ever-growing epidemic. Their incentives must change. Instead of paying clinicians simply to diagnose, prescribe, and deliver therapy, the system must reward outcomes: bonuses for helping people return to work, education, or independent living. Outcome-based payments would align provider incentives with recovery rather than long-term service use. Eligibility for such bonuses should be determined by independent functional assessors, not treating clinicians.

New health messaging would also help. National awareness campaigns, hotlines, and education initiatives currently funnel people into the mental health system. We need messaging that emphasises prevention and recovery with equal vigour.

The stated goal of the mental health system should be to help people leave it and lead full lives. This requires a cultural shift in which we recognise distress as a normal part of life, not always as pathology. Rather than fostering dependency on drugs, pensions, and psychiatrists, the system should encourage agency—teaching people to manage moods, relationships, and setbacks without defaulting to diagnosis. Where social policy gets in the way, the policies themselves should change. Most importantly, we need to celebrate independence. Discharge from services should be viewed as an achievement, not as abandonment. Such a shift would not reduce compassion; it would deepen it by distinguishing those who truly need lifelong care from those who need understanding, structure, and purpose.

Re-think Data Collection

Redirecting the mental health system will require a fundamentally new approach to data collection. Australia currently collects vast quantities of mental health data, but little of it measures what matters. The focus is on inputs such as spending and sessions delivered rather than outcomes. A reformed system would track the measures needed to assess effectiveness. Specifically, reliable information is needed on three central questions:

Functional recovery. What percentage of people move from the mental health system into employment, education, or independent living?

Duration in the system. How long are people spending in care? How many exit, and how many remain indefinitely?

Distributional equity. Are resources directed toward severe conditions with the greatest need, or absorbed by mild ones?

Transparent reporting on each of these would expose whether reform is working. If mild cases continue to rise and absorb disproportionate funding, we will know it has failed.

Wherever Possible, Handle Problems Outside the Mental Health System

Speaking in ‘tongues’, or glossolalia, is the practice of uttering repetitive speech-like sounds that are not recognisable as a known language. In a Pentecostal church, the same behaviour would be viewed as a spiritual gift from God. In the classroom or workplace, such behaviour would be seen as highly deviant, perhaps even a psychosocial disorder. The same behaviour can be deviant or mainstream depending on the context in which it occurs. Medical diagnoses such as diabetes, pneumonia, or measles do not change with social context; psychosocial diagnoses do.

Contextual factors (social, cultural, and developmental) also influence how behaviour is interpreted and treated. For many of the difficulties currently captured in the psychiatric net, context offers better explanations for their cause and treatment than neurodiversity or chemical imbalances. To illustrate the point, consider ADHD.

The DSM-5 specifies that ADHD begins before age 12, usually in primary school. Almost all school systems set fixed age cut-offs for enrolment. Consequently, students born just before the cut-off are nearly a year younger than some of their classmates. Yet they are expected to meet the same behavioural and academic standards. Numerous studies from Canada, Denmark, and the United States have shown that the youngest children in a primary school class are significantly more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD than their older classmates.[61],[62],[63] Even in grades five and eight, the youngest children are twice as likely to be taking stimulants as their older classmates.[64] This discrepancy is more pronounced among boys, who, on average, mature later than girls in key areas such as attention, impulse control, and executive function.

It has become increasingly common to interpret difficulties in meeting classroom demands as evidence of an underlying neurodevelopmental disorder, most commonly ADHD, and to respond with pharmacological treatment. The educational and developmental context in which these behaviours arise receives far less attention than the presumed pathology of the child.[65]

A contextual approach would reverse this. Rather than relying on stimulant medication, sometimes for many years, it would prioritise adjustments to school entry and classroom organisation: delaying entry for younger children, or structuring cohorts so that younger and older students are taught separately. These are not clinical interventions. They are policy and administrative reforms informed by well-established developmental science.

Staggered or flexible school entry is being trialled successfully in some jurisdictions.[66],[67] Evidence suggests that such structural adjustments reduce behavioural problems with fewer risks than long-term stimulant use.[68] Pharmacological treatment may manage symptoms, but policy-level adjustments directly address the underlying developmental context.

Why, then, do education systems continue to rely so heavily on medication? The reasons are largely bureaucratic and institutional. Tailoring school entry to developmental readiness increases administrative complexity and cost: cohorts progressing at different rates require additional assessment, more flexible staffing, and more complex timetabling. For families, delayed entry can also impose genuine financial pressure, particularly where childcare costs are high and alternatives are limited.

There are also broader system-level dynamics at work. ADHD diagnoses have become embedded in institutional arrangements that link diagnostic status to treatment, specialised services, and, in some cases, additional educational resources. A substantial reduction in diagnosis rates would have downstream effects on pharmaceutical suppliers, clinical practice, and school funding mechanisms. This does not imply deliberate self-interest or coordinated intent on the part of clinicians, educators, or drug companies. It reflects the reality that the systems in which they operate have come to depend on medicalised solutions.

The relevance of contextual explanations extends beyond ADHD. Depression and loneliness offer two further examples. The consequences of unemployment, such as financial strain, housing insecurity and social pressures, greatly increase the risk of anxiety, substance abuse and the chance of a major depressive episode.[69] The association between unemployment and depression is particularly strong. Adults receiving unemployment benefits are twice as likely to be diagnosed with clinically significant anxiety and depression as their employed counterparts.[70] In such cases, a strong economy, secure employment and affordable housing are among the most effective antidepressants available, often more powerful than pharmacological treatments, whose efficacy remains contested.[71]

Loneliness, frequently described as a public health crisis, is often a by-product of urban design, social fragmentation, and the displacement of traditional civil society by large government programs. Rebuilding civic associations such as churches, choirs, and sports clubs restores belonging more effectively than therapy. As the Harvard Study of Adult Development concludes, ‘close relationships, more than money or fame, are what keep people happy and healthy.’[72]

In each case—ADHD among the youngest children, depression and loneliness tied to social circumstances—the most effective response lies not in diagnosis and medication, but in addressing the external, social circumstances that produced the distress.

Thriving Kids

For decades, mental health advocacy has focused on awareness and expansion: more diagnoses, more services, more funding. In August 2025, the Australian Government announced Thriving Kids, a multibillion-dollar program jointly funded by the Commonwealth and state and territory governments.[73] Thriving Kids will focus on identifying developmental concerns earlier and establishing a national system of supports for children aged eight and under with mild to moderate developmental delay and autism. Children who may not require long-term, intensive support will be directed away from the NDIS and into community-based services within schools, health services, and local communities.

Although details remain sketchy, there is a danger that Thriving Kids may continue the trajectory of the past 50 years. It could become another diagnostic pipeline — lowering thresholds for intervention, professionalising childhood development, and channelling children into long-term service pathways. ‘Early identification’ sounds promising, but it could easily become the early creation of psychosocial disorders. And once a child is labelled, the label does damage of its own: it shifts responsibility away from the child, undermines the expectation of normal development, and teaches children to understand themselves as deficient rather than growing.

A genuinely different model is possible. Thriving Kids could support families without diagnostic labelling, expect developmental catch-up, provide time-limited assistance, and reserve specialist services for children with severe developmental disorders. Success would be measured not by the number of children entering the system, but by the number leaving it.

To work, the program should be led by educators, developmental psychologists, and community organisations rather than psychiatrists. It should not confine itself to very young children but extend through middle childhood, when neurodevelopmental catch-up is most likely. It should offer mentoring, play-based learning, and parent coaching without requiring any diagnosis. Outcomes should be measured in terms of resilience, function, and social competence, not psychiatric codes.

How Thriving Kids is ultimately designed will reveal whether Australia is prepared to test a genuine alternative to therapeutic expansion.

What Reform Looks Like

A mental health system built on these principles would look fundamentally different from what exists today. It would:

- Guarantee intensive and permanent support for severe and persistent psychosocial disturbance, through a dedicated funding stream, clear eligibility criteria focused on function, and genuinely coordinated provision.

- Provide brief, goal-directed professional support during acute crises, with explicit expectations of discharge and financial incentives for successful resolution rather than service retention.

- Remove policy barriers to flourishing, particularly in housing supply, labour markets, and early-years education structures that generate avoidable distress.

- Support families and communities directly, through adequate carer payments, tax relief, rapid access to respite, and low-bureaucracy grants to community organisations.

- Realign incentives so that clinicians, schools, providers, and governments are rewarded for functional improvement and exit, not for service volume and diagnostic growth.

- Demand serious evidence, including long-term outcomes and direct comparisons with non-therapeutic alternatives such as housing assistance and direct family support.

- Tell the truth about limits—acknowledging that governments cannot manufacture meaning, belonging, or purpose through service systems.

Conclusion: From Diagnostic Expansion to Human Flourishing

Australia has reached a point of decision. For decades, we have poured ever-increasing sums into mental health services, yet rates of illness, disability, and distress have risen rather than fallen. The problem is not a lack of compassion or commitment. It is compassion without proportion. We have built a diagnostic marketplace that rewards overidentification, subsidises dependency, and leaves the profoundly distressed waiting at the back of the queue.

The result is a system that medicalises psychosocial problems and encourages both individuals and providers to anchor themselves to diagnostic labels. Too many people are drawn into care they do not need, while those with severe, life-limiting psychiatric illness struggle to obtain the intensive support they cannot live without. In trying to help everyone, we have failed the very people who depend on us most. The system produces patients rather than health, and measures success by how many people it treats rather than by how many people no longer need it.

Reform begins by restoring distinctions. Severe and mild conditions are not the same. Functional impairment, not psychiatric nomenclature, should determine eligibility and support. Situational problems—those arising from housing, unemployment, educational failure, family conflict, or unsafe environments—must be addressed for what they are, not converted into permanent medical conditions. And incentives that reward ongoing illness must be replaced with incentives that reward progress, capability, and independence.

A humane system does not shrink compassion; it sharpens it. It makes room both for the child with profound autism who may never speak and for the teenager whose struggles reflect loneliness, instability, or insecurity rather than a lifelong disorder. It honours human suffering without confusing it with disease, and it promotes recovery not as a distant ideal but as the expected outcome.