Home » Commentary » Opinion » Afghanistan withdrawal: Redefined US role not a signal of retreat

· The Australian

September 11 is not just shorthand for the terrorist attacks 20 years ago. It also takes in the US response, including a global war on terror, which led to the loss of American blood, treasure, credibility and prestige in the greater Middle East.

September 11 is not just shorthand for the terrorist attacks 20 years ago. It also takes in the US response, including a global war on terror, which led to the loss of American blood, treasure, credibility and prestige in the greater Middle East.

Whereas in 2001 the US was the lone superpower, universally respected and envied for its economic and military might, today the world worries more about US weakness and ineptitude: it is much more aware of its limitations – and less impressed.

The temptation, scarcely resisted, is to blame all this on Joe Biden or Donald Trump. In fact, blame lies primarily on not just George W. Bush’s administration, but on ideas about American power and principles that were widespread in the decade leading up to 9/11.

With the end of the Cold War in 1989-91, America emerged as the most powerful state in recorded history. These were the days of “the unipolar moment” (Charles Krauthammer) that would usher in the “end of history” (Francis Fukuyama) – the rapid and universal acceptance of liberal democratic values. There was a widespread consensus in Washington and, indeed, many parts of the world (including many contributors to these pages) that the US, as the sole remaining superpower, should exercise benign global leadership.

Soon enough, though, Bill Clinton was president and the US had no clear plan in place to exploit its unexpected predominance, nor did it adopt one: the military often seemed more concerned with having exit strategies in place than with implementing ambitious, open-ended, foreign policy projects – whether that concerned the Balkans, Haiti, Somalia or places entirely avoided such as Rwanda. This restraint involved no loss of prestige or influence.

But things changed dramatically on 9/11. US outrage over the terrorist attacks, taken together with American exceptionalism and the mental habits of global liberal hegemony since the collapse of the Soviet Union, gave US leaders a clear overriding purpose lacking since the end of the Cold War – and that some, including the neo-conservative critics of Clinton, had been strenuously demanding.

Of course, the US had no choice but to respond to the terror attacks. Washington carefully avoided a declaration of war against Islam. Allies were enlisted. The Taliban was routed with little bloodshed and al-Qa’ida was on the run.

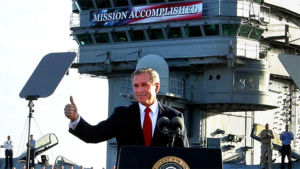

However, this potent sense of victory allowed the Bush administration and the neo-conservatives to make the case for invading Iraq and replicating what happened in Afghanistan. Suddenly, the political balance had shifted away from the prudence and moderation of the 1990s toward conceptual boldness and the ambitious assertive use of America’s vast power.

Thus, the Bush doctrine of preventive war, democracy promotion and aggressive unilateralism was born: it encouraged the belief the US could impose its will and leadership across the globe. It should be stressed this was a bipartisan endeavour: a senior Republican adviser, later revealed to be Karl Rove, boasted: “We are an empire now, and when we act we create our own reality.” Democrat Hillary Clinton declared: “It is in our DNA (to believe) there are no limits on what is possible or what can be achieved.” But although the US possessed the military means to defeat Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq and the Taliban tyrants in Afghanistan, there is not an American solution to every problem. In fact, there are a good many problems for which there may be no solution at all.

Add to this the fact Americans do not understand tribally divided societies and ethnically fractured people. Nor do they have the attention span or staying power to engage in an active, interventionist policy of nation-building and democracy promotion. And so the Bush doctrine failed, because it was impossible to implement in the first place. It was a utopian goal that was beyond the reach of any nation.

This history has been obscured by the contemporary anguish over US foreign policy, especially in the wake of Washington’s humiliating withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Biden, not unlike Trump, wants to redefine the US role in the world in a way that reflects the changing circumstances – the end of unipolarity and a recognition of the limits of American power. Contrary to received wisdom, this does not amount to a “global retreat” – a signal to disengage with the rest of the world and retreat to fortress America. It is about reordering strategic priorities away from the “endless wars” of the Middle East and toward the Indo-Pacific in the face of a real threat: an increasingly assertive China bent on upsetting the regional status quo.

Most pundits in America, Australia and elsewhere who have slammed Biden in recent weeks came of age during the unipolar moment. They thought the US had found the magic formula for creating a peaceful and prosperous liberal world order. And they saw a benign America as the driving force behind that enterprise.

Slowly but steadily, it has become evident the enterprise was, as distinguished University of Chicago professor John Mearsheimer has argued, a delusion. Trump’s “America First” election in 2016 was a severe body blow to that vision, but he did lose in 2020, and his successor promised to restore much of the liberal democratic order. But it’s not working out that way. The fall of Kabul is a graphic reminder that Fukuyama, Krauthammer and their acolytes were wrong: history has returned with a vengeance and a Pax Americana is not sustainable.

One can oppose Biden’s big-government and left-wing cultural agenda at home, as I do, and still recognise his justified scepticism about policing messy places like the greater Middle East. For his sins, he has been widely denounced. But according to a Washington Post poll on the weekend, 77 per cent of the American people support his withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Moreover, far from retreating from the world, Biden is simply redefining the US place in it: with the return of great-power security competition, Washington wants to reorder strategic priorities away from the greater Middle East toward Asia. Keeping in check China’s regional ambitions is in America’s national interest, and it commands broad bipartisan support; fighting the Taliban after 20 years of war is neither sustainable nor popular.

Many Australians attack Biden for the withdrawal from Afghanistan. But they should be thrilled he has pulled America out of this unwinnable war and wants Washington to focus more on the Indo-Pacific region.

America can’t be the global policeman, but it can be heavily engaged in areas that really matter. Such a change in direction marks not just a proper understanding of America’s interests, it also repudiates much of the post-Cold War idealism that culminated in the hubris and perils of post-9/11 US foreign policy.

Afghanistan withdrawal: Redefined US role not a signal of retreat