Home » Commentary » Opinion » Does Morrison have Howard’s heart?

· Financial Review

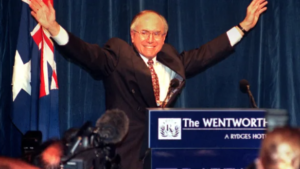

It was 25 years ago on March 2 that John Howard defeated the Labor government in a landslide election. He went on to become the nation’s second-longest serving prime minister and helped set the scene for the longest economic boom since the gold rushes of the 19th century.

It was 25 years ago on March 2 that John Howard defeated the Labor government in a landslide election. He went on to become the nation’s second-longest serving prime minister and helped set the scene for the longest economic boom since the gold rushes of the 19th century.

To grasp the impact of Howard’s government, it is necessary to recall Australia’s condition in the early-to-mid 1990s. It was a time of Paul Keating’s “recession we had to have”, double-digit unemployment, 17 per cent interest rates, record-high budget deficits and a $96 billion national debt.

Fiscal discipline seemed like a lost cause while tax reform was deemed mission impossible. In the “un-losable election” of 1993, the electorate rejected John Hewson’s goods-and-services tax. The Senate was, in Keating’s memorable language, “unrepresentative swill”.

At the same time, the nation had to put up with the Maritime Union of Australia’s industrial intransigence and its ideological hostility towards sensible workplace agreements. We had 2 per cent of world trade, Howard later recalled, but 25 per cent of dock disputations.

All that changed in 1996. Ably supported by several outstanding ministers – most notably Peter Costello, Alexander Downer, Peter Reith, Philip Ruddock and John Anderson – Howard was doggedly dedicated to using power to change Australia for the better.

His government balanced the national books, wiped out government debt, reformed welfare and cut taxes as it implemented a GST. Telstra was fully sold so it could properly serve its customers and shareholders rather than its political masters.

The Howard government also took on the wharfies and delivered dramatically improved waterfront productivity and greater reliability in some of the nation’s biggest-volume container ports. And although industrial relations reform was wound back under Labor successors, it made it easier to loosen organised labour’s grip on business.

True, Howard was as given to paternalism and pork-barreling as any of his predecessors. It’s also true that much of the groundwork for Australia’s transformation from a heavily protected and subsidised closed shop into a high-growth, less-inflation prone, market-oriented powerhouse had been laid during the 1980s and early 1990s.

However, it is worth remembering that Howard — in opposition as shadow minister, party leader and, briefly, backbencher — crucially supported the Hawke government’s reform agenda, an act of bipartisanship that Labor did not extend to Howard in power.

Still, during Howard’s near 12-year tenure, Australians became a relaxed and self-confident people. Everything that should be up – income, economic growth, the stock market, the budget surplus, consumer and business confidence and living standards – was up, while everything that should be down – unemployment, inflation and (historically speaking) interest rates – were down.

In 2004, The Economist magazine dubbed Australia the “miracle economy”. All this as Australia weathered the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98, the US tech wreck of 2000-01 and Australia’s worst drought in a century.

Yet as Australia marks this important political anniversary, there is one urgent question that must be answered: can Scott Morrison and Josh Frydenberg repeat what Howard and Costello did, and pull Australia back out of the morass?

The truth is that now, 25 years after Howard’s legendary victory, Australia could face troubling economic times. Piling up more debt will not be sustainable when interest rates eventually rise. As a result, everyone wants to know if Morrison has the vast inner moral strength to fight the intellectual and political battles needed to extend the recovery into a more durable prosperity.

Answering this question is tricky because the problems are in some respects harder to solve – from tax and workplace to infrastructure and skills and vocational training. In one sense, Howard had it easy. Both in opposition (1983-96) and in government (1996-2007), it was relatively simple to identify what Howard today calls “low hanging fruit”: financial deregulation, floating the dollar, tariff cuts, tax and labour market reform.

For Morrison, however, it is more complicated. The Senate is more obstructionist, the media more polarising and ministers seem less willing or able to prosecute reform than was the case a quarter-century ago. For the past year, we have faced a once-in-a-century global pandemic.

Though the challenges are different, there are still many lessons to be learnt from Howard’s memorable government. Howard was a politician who combined strong convictions with a streak of pragmatism. He was always prepared to risk failure rather than take the easy choice. And he had a broader philosophy about reform, likening it to competing in a never-ending foot race. “You know you will never reach the finishing line,” he argued, “but you dare not stop because your competitors will surge past you.”

If Morrison can summon up the same courage and implement overdue supply-side reforms, then we will have yet another reason to be thankful for Howard’s impressive legacy.

Does Morrison have Howard’s heart?