Home » Commentary » Opinion » Living with the panda and the dragon

· Ideas@TheCentre

There is an emerging consensus that Australia is entering a new and much tougher era in our bilateral relationship with China. But there is also a lack of consensus on the nature and extent of the challenges we face in reconciling our economic interests with a growing divergence in values and security interests.

There is an emerging consensus that Australia is entering a new and much tougher era in our bilateral relationship with China. But there is also a lack of consensus on the nature and extent of the challenges we face in reconciling our economic interests with a growing divergence in values and security interests.

This was apparent last Thursday when CIS held a debate to launch a new pilot project called China and Free Societies.

Australia is poised to broaden and deepen its bilateral relationship with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) — as signalled by the recent pledge of $44 million for the new National Foundation for Australia-China Relations to ‘turbocharge’ engagement with the Asian superpower. But engagement will also be limited by national security concerns, as the recent decision to ban the Chinese telco Huawei from the 5G network demonstrates.

China is ruled by an increasingly authoritarian party-state with very different values and governance — and these differences are becoming starker as the PRC becomes more assertive. Australia also earns one in three of its export dollars from trade with China, raising fears that this economic dependence could circumscribe political independence.

The PRC has shown a willingness to use economic coercion to punish governments whose sovereign policy choices do not align with Beijing. But arguably more effective is the use of indirect threats such as delaying imports of Australian coal or favouring other suppliers.

Journalists have noted that discussion of risks and uncertainties in the bilateral relationship has been mostly absent from the federal election campaign, despite mounting concern in foreign policy circles. And yet the incoming government is likely to come under intense pressure from Beijing as Canberra tries to renegotiate the terms of engagement — alongside a gnawing sense that China may now be strong enough to dictate these terms.

China is a great power, but it is worth remembering that it is not the only significant country in our region. As former diplomat Geoff Miller has pointed out, other significant players include Japan, India and Indonesia. The latter two have young populations, fast-growing economies, and I would add that all three are democracies.

Australia should engage with China and hedge the risks by deepening ties with other regional democracies, alongside the US alliance, as the regional balance of power changes.

Sue Windybank is convenor of the China and Free Societies project at The Centre for Independent Studies.

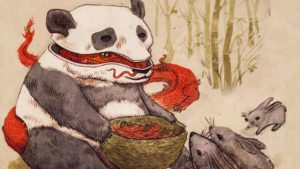

Living with the panda and the dragon