Home » Commentary » Opinion » What would Menzies think of today’s Liberal Party?

· Canberra Times

Labor’s 20 per cent result in the weekend’s Hunter by-election is being seen as a warning to both state and federal Labor. But Liberals should also more critically assess the by-election’s implications, along with other recent state election results and developments, when their Federal Council meets this week in Canberra.

Labor’s 20 per cent result in the weekend’s Hunter by-election is being seen as a warning to both state and federal Labor. But Liberals should also more critically assess the by-election’s implications, along with other recent state election results and developments, when their Federal Council meets this week in Canberra.

Although Federal Council is largely an orchestrated public relations exercise these days, it nevertheless bring together Liberals from around Australia and provides an opportunity for serious discussion about the party’s future, beliefs and impending federal election.

There is much to ponder.

The Coalition’s success in Hunter and the recent Tasmanian results need to be considered in relation to March’s West Australian election debacle, the Berejiklian government’s continuing ministerial problems, and Liberal insipidity in Victoria. In Queensland, a federal Coalition stronghold, the LNP has numerous local issues and lost lanother state election last year – its eleventh loss out of the last 12 state polls.

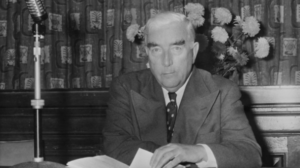

Liberals could do well to consider how founder Sir Robert Menzies might assess the party today.

While we cannot exactly know Menzies’ views, a good assessment can be made based on his opening address to delegates at the Albury Conference in 1944 when the Liberal Party was founded, where he outlined the flaws of its predecessor, the United Australia Party (UAP).

Many know Menzies’ ‘Forgotten People’ broadcasts, but few are aware of his Albury opening address – the ‘Forgotten Speech of 1944’ which provided the policy and organisational principles that helped the Liberals dominate Australian politics.

The first defect was that there was “no true nexus between the federal parliamentary party and those who are to do the political work in the field”. UAP councils were little more than media events or fund-raisers, rather than hard policy debates where MPs could be held answerable to their supporters. How does the current Federal Council measure up these days?.

Second, apart from occasional election policy statements, there was “no comprehensive statement of our political objectives”. UAP members had little idea about its basic principles.

Many supporters are not sure what the Liberal Party stands for these days given the Morrison government’s budget spending extravaganza, numerous policy ‘cave ins’.

Third, the UAP had “no…process of consultation between those in and those out of parliament” to update policy.

How does this compare today given how the views of the organisational wing are ignored and bypassed and campaigns and policy priorities at both state and national levels are dominated leaders offices, personal staff and central campaign headquarters?

Fourth, the UAP was known by too many names and had lost its intrinsic significance. Moreover, Menzies elsewhere observed that it had become corrupted by organised factions to which many members gave their prior loyalty, and often even by coalitions of factions conspiring against the remaining unaligned members. Is this not the Liberal Party today?

Fifth, there was no properly organised arrangement for conveying the party’s views to the public. Branches in the UAP, for example, were often mere phantoms, existing only on paper, irrelevant to their communities and without the vital capacity to act as two-way conduits between the government and the public.

Sixth, there was “no constant political organisation in the electorates”. UAP membership numbers had fallen to insignificance. Lacking a popular base, professional field staff and other essential resources, the UAP was incapable of real political campaigning but was forced to waste its money on crude public relations and expensive advertising campaigns. Similarly, today’s Liberal Party’s membership has shrunk, and it seems it is pollsters and focus groups that drive policy.

Seventh, the UAP had lost the interest and support of “young men and women” who looked elsewhere for their inputs into national politics. Does this not reflect current voting trends?

Finally, Menzies believed “we lean too heavily upon individual donations and have no adequate rank and file finance”. The UAP had no effective finance code. Menzies insisted policymaking be insulated from the fundraising process.

All responsible leaders have agreed – but every former party director could write a book about that. Moreover, public funding has made all political parties, but especially the Liberals, lazy in growing their membership base and having an independent income stream.

If Menzies applied the same criteria to the Liberal Party today, he would probably be disappointed.

When Morrsion became prime minister, he made a big deal of having his ministry meet in Albury to renew their ‘pledge’ to the Menzies legacy. Perhaps he, and others, should read Menzies’ ‘Forgotten Speech’. There is much to learn.

Dr Scott Prasser is Senior Fellow at the Centre for Independent Studies and author of the recent book Menzies: Man or Myth

What would Menzies think of today’s Liberal Party?