In 1984, Milton Friedman reminded us that “there is nothing so permanent as a temporary Government program”. And so it has come to pass that the Future Fund, which was envisaged to have a finite life, is now seeking immortality.

The Future Fund is an uniquely Australian creation. Often — and arguably erroneously — described as a sovereign wealth fund, it has been given near-mythical credence. Its board is not comprised of mere directors but rather ‘Guardians’. The Future Fund’s existence has attained such an exalted economic status in Australia that despite its recent questionable economic contribution, it has spawned several new ‘children of Future Fund’ established at the Commonwealth and State levels.

Approaching 18 years of age, however, it is now time to consider the future of the Future Funds because as Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson once quipped: “When the facts change, I change my mind”. And when it comes to the Future Fund, the facts have changed significantly since it was established in 2006. The economic case for its continuing existence has since eroded.

In Australia’s current economic straits, the most economically responsible action for a government to take is to liquidate, in an orderly manner, the holdings of the Future Funds and pay down debt. With every additional dollar of Commonwealth debt accumulated and every interest rate increase, the case for closing and retiring the Future Funds becomes ever more compelling.

Importantly also, once all Future Fund investments have been liquidated, the Future Fund entity should be permanently shut down to reduce the political incentives for the establishment of ‘grandchildren of Future Fund’ .

About the Future Fund

Strategy and policy are not determined in a vacuum. They are contextual and a function of the facts at the time. And when the facts change, strategy and policy frequently need to change.

The purpose of the Future Fund was to finance or pre-fund the Commonwealth’s unfunded superannuation liabilities, which at the time was the largest liability on the Commonwealth’s balance sheet. The superannuation liabilities for four Commonwealth superannuation schemes were either completely unfunded or only partly funded requiring payments to beneficiaries on a ‘pay-as-you-go’ basis from the Commonwealth budget. This imposed the cost of financing liabilities accrued in the past onto taxpayers of the day.

Although there are now several other ‘Future Funds’, the stated objective of the original Future Fund was to fully underwrite these unfunded superannuation liabilities by 2020. In his 2005 second reading speech in support of the Future Fund Bill, Treasurer Costello noted that these unfunded superannuation liabilities stood at $90 billion at 30 June 2005 and were projected to be $140 billion by 2020. Costello said that “The Future Fund will be invested with the aim of accumulating financial assets sufficient to offset the government’s unfunded superannuation liabilities by 2020.”

Inferred at establishment was that it would take approximately 15 years to fully fund these liabilities and that the Future Fund balance would, from there, descend to an orderly close as hitherto unfunded superannuation liabilities expired. However, the Future Fund will be 18 years old next year, and it does not appear that it will meet this purpose any time soon.

Context

When the Future Fund was established, the Commonwealth budget was in surplus and the Commonwealth’s net debt position was negative. For many Australians, it may be difficult to remember a time when the Commonwealth had negative net debt, but such was a time earlier this century. The Commonwealth may have a budget surplus today, as it was earlier this century, but it is currently very far from having a negative net debt position.

When the government of the day was presented with a situation of negative net debt and receipts exceeding outlays, the government had three essential options:

- to reduce revenues through actions such as tax cuts,

- to increase spending — either permanently or temporarily given the economic cycle,

- to save the surplus, further increasing negative net debt.

The government chose a combination of the three, with the budget surplus deployed to the Future Fund. The Future Fund was thus established in 2006 and seeded with the proceeds of the Commonwealth’s 2006-2007 budget surplus, joined later by the transfer of the balance of the Commonwealth’s holdings in the privatised Telstra. Together, these allocations of capital provided the basis of what is now one of Australia’s largest asset managers.

Forecast versus Actual

As is common with most budgets and financial plans, forecasts and actuals often fail to converge; not due to forecasting errors but due to the future evolving different to what was expected.

In 2005, the Commonwealth’s unfunded superannuation liabilities were forecast to be $140 billion by 2020. According to the Australian National Audit Office, the balance at 30 June 2021 was $408 billion declining to $322 billion at 30 June 2022. This decrease was due primarily to a change in the discount rate. However, given increased life expectancy — coupled with Australia’s current inflationary environment driving superannuation indexation — this liability will likely increase significantly again when next assessed.

At the time of its establishment, it was estimated that the original Future Fund would have sufficient resources by 2020 to relieve the budget of the need to meet the cost of these unfunded superannuation obligations. This is likely why the founding legislation permitted Future Fund drawdowns only from 1 July 2020. However, the government announced in the 2017-18 budget that it will refrain from making withdrawals until at least 2026-27; suggesting that further capital would need to be accumulated.

The balance of the original Future Fund was approximately $203 billion as at end March 2023, sufficient to meet the 2005 forecast, but nowhere near sufficient to meet the 2022 figure.

Meanwhile, Commonwealth’s net debt position in 2007 was negative $30 billion but positive $550 billion in 2023 — a $580 billion increase. Gross debt in 2023 is also approaching $1 trillion, all while the Commonwealth budget is still meeting the annual costs of the pension liabilities the Future Fund is meant to cover.

Is the Future Fund a Sovereign Wealth Fund

While frequently described as a ‘sovereign wealth fund’, this is not strictly accurate for the Future Fund. A sovereign wealth fund is a state-owned investment fund in which the principal and returns are used for the benefit of future generations. Although providing an indirect benefit by reducing payments from the budget, the direct beneficiaries of the original Future Fund’s capital and (net) investment returns are not future generations of Australians but rather past generations of public servants.

The Future Fund is not for a specific future investment purpose, such as to build infrastructure in the future, nor for tax smoothing, but rather to relieve the budget of an ongoing liability. This is an important distinction. In an accounting sense, the Future Fund is more of a provision than an investment.

This is a semantic distinction and not an economic one, because money is fungible. But truth in advertising is still important; because it is unlikely that the Future Fund’s public credibility would have the same currency were $200 billion of public resources allocated to something called the ‘Funding Retired Public Servants Pensions Fund’. Importantly also, the incentives and infrastructure for the establishment of now several ‘Children of Future Fund’ might not have existed.

Children of Future Fund

Since its inception, the Future Fund has been given investment mandates beyond its original unfunded superannuation liability purpose. The Future Fund now also manages:

- the Medical Research Future Fund

- the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Land and Sea Future Fund;

- the Future Drought Fund’

- the Disaster Ready Fund; and

- the DisabilityCare Australia Fund.

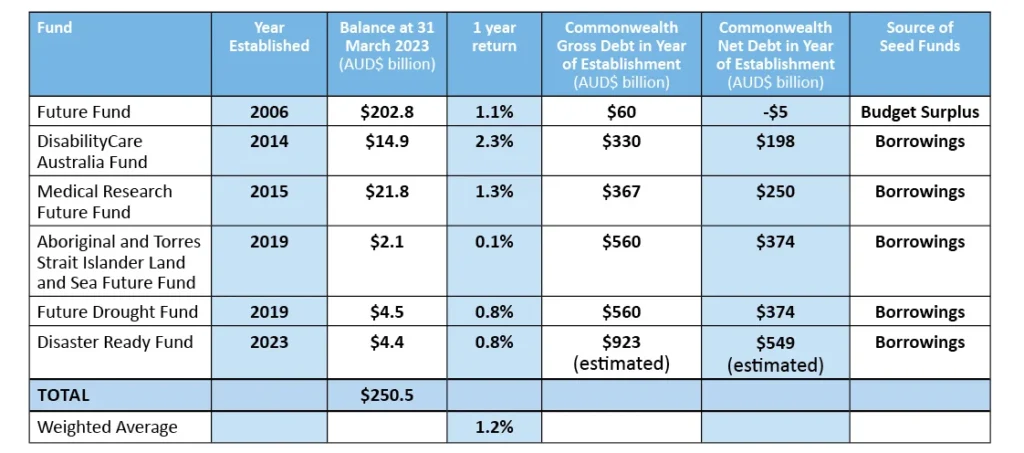

At 31 March 2023, total assets under management across all Future Funds exceeded $250 billion.

These Children of Future Fund operate in a structurally and strategically different manner to the original Future Fund. The original Future Fund is designed so that the principal (original capital) and net returns will be used for the specific purpose of financing superannuation liabilities. The Children of Future Fund, however, are designed so that the principal is broadly preserved and only the net investment returns are used for their designated specific purposes. This results in a different investment risk profile for the Children of Future Fund — essentially capital preservation — and is reflected through the investment strategy and capital allocation decisions of the asset managers.

If the Albanese government is successful in passing its Housing Australia Future Fund (HAFF) legislation, a further $10 billion would be borrowed on behalf of the Commonwealth and allocated to the Future Fund to manage. The HAFF would also be structured akin to the other Children of Future Fund with an objective of capital preservation and use of investment returns only.

By way of contrast, the former NSW Coalition government considered a similar strategy. In 2021, it was reported that NSW Treasury and TCorp recommended to then-treasurer Dominic Perrottet that the NSW government borrow $20bn to invest in shares and other financial assets. This would be the strategic equivalent of a Child of Future Fund.

The $20bn of debt would be invested through the ironically named Debt Retirement Fund. It was further reported that, NSW Treasury and TCorp officials argued such a strategy would deliver higher long-term returns for citizens. S&P Global Ratings warned pursuing such a strategy “would weaken its (NSW) credit risk profile”.

The head of the NSW Parliamentary Budget Office described this strategy as “very risky”. Then opposition, now current Labor NSW Treasurer Daniel Mookhey said that it would be “crazy to plunge taxpayers even further into debt and then gamble that money on the stock market and in other risky trades.” The common observation from all three highlighted the risk in such a strategy, and this was at a time of near zero interest rates.

Across seven funds, including HAFF should legislation pass, more than $260 billion of public resources would be managed. Approximately $200 billion for the original Future Fund and $60 billion for the Children of Future Fund. This assumes there will be no erosion in the value of funds under management from 31 March 2023.

The Children of Future Fund are also not strictly sovereign wealth funds either because they are not funded through savings but rather through borrowings. This makes them more akin to leveraged-investment funds whereby funds are borrowed and invested in expectation (and hope) that net returns exceed the cost of borrowing.

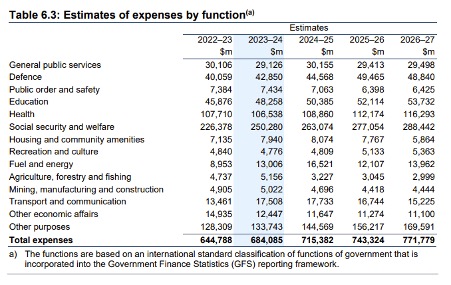

Source: Commonwealth Budget Papers

Net Debt versus Gross Debt

It is important to focus on gross debt as well as net debt when considering the Commonwealth’s true financial standing. While it may be politically preferred to focus on net debt because it is a smaller number, gross debt is in many respects the more relevant metric.

The main difference between net debt and gross debt is the value of ‘financial’ investments such as the original Future Fund, the Children of Future Fund, and other investment vehicles such as the Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC).

From a whole of government perspective, to assess the economic contribution of the Future Funds, it is necessary to account for all cash flows and risks. The Future Fund only accounts for the benefits and not all the costs.

The $250 billion of capital currently managed by the Future Fund has an opportunity cost — the cost of debt — which is borne by the budget. Using the current RBA official cash rate of 4.1 per cent as a proxy, this implies that the capital cost of the Future Funds, paid by the budget, is approximately $10 billion per annum. Put another way, the Future Funds need to generate 4.1 per cent returns after costs to just break even, and to break even on a cash basis only. This does not account for the investment risks borne by the Future Funds.

The interest cost on $250 billion ($10 billion) suggests that, based on the most recent Commonwealth budget, maintenance of the Future Funds is effectively the 10th largest Commonwealth expense by function, an amount greater than what the Commonwealth allocates for ‘housing and community amenities’”.

Source – 2023-2024 Budget Statement 6: Expenses and Net Capital Investment

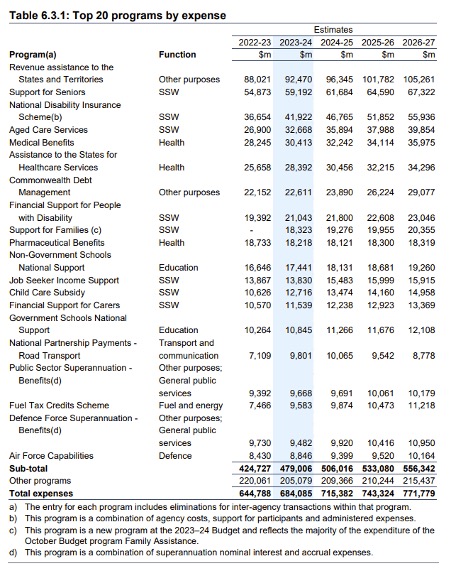

Based on expenditure by program, this interest expense ranks in the top 20 Commonwealth government programs.

Source – 2023-2024 Budget Statement 6: Expenses and Net Capital Investment

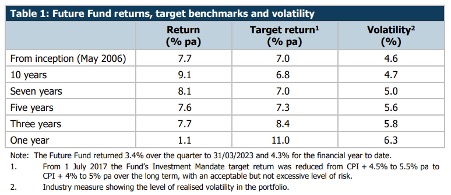

Granted, Future Funds cash returns have historically exceeded their cost of capital, at question is whether they will be able to continue to do so in the future. Since its inception in 2006, the original Future Fund has generated an average annual 7.7 per cent return. However, its most recent 12-month return was 1.1 per cent, below the cost of borrowings. While a positive absolute return, it was still an economic loss for the Commonwealth.

Each of the current six funds has an investment return target that guides its investment strategy and risk tolerance. The original Future Fund, which accounts for approximately $200 billion of the $250 billion total, is chartered with target rate of return of 4.0 to 5.0 per cent per annum above inflation in large part to account for investment risk. In the current inflation environment, this translates to an investment return target of 10.0 to 11.0 per cent. As Sir Humphrey Appleby might describe, this is a ‘courageous’ target.

Per the standard investment warning, past performance is not a guide to future performance. This is particularly the case as global investment markets have entered a more volatile period with high inflation, de-globalisation, and increased incidence and risk of military conflicts. In particular, Ben Samild, the Future Fund’s recently promoted Chief Investment Officer, describes this target as “incredibly hard” to achieve.

Investment Risk and Reward

As noted above, there are currently six Future Funds with a total funds under management of more than $250 billion at 31 March 2023. Should the Albanese government pass its Housing Australia Future Fund legislation, a seventh fund will be seeded with a further $10 billion of borrowing.

Unlike the situation that existed when the original Future Fund was established, the capital within the six current Future Funds is not back by negative net debt, but for all intents and purposes, through borrowings. This is because the capital allocated to the Future Funds could otherwise be used to reduce debt or on other budgetary initiatives.

Using the current RBA official cash rate of 4.1 per cent as a proxy, the cost to the budget of maintaining the Future Funds is approximately $10 billion per annum. To just stand still on cash basis, the Future Funds need to generate a 4.1 per cent return after expenses. But breaking even on a cash basis does not compensate the Commonwealth for the investment risk it is exposed to by the Future Funds. This is why the Future Funds have higher investment return targets to reflect this investment risk.

While perhaps generating a positive net contribution (return above the cost of Commonwealth borrowing), the original Future Fund did not meet its target return over the past three years — inferring a risk-adjusted loss.

Source – Future Fund Portfolio update to 31 March 2023

Given that interest rates are rising, domestically and internationally, consequently increasing interest service costs within the budget, the Future Funds will need to generate ever increasing returns to avoid a whole of government risk adjusted economic loss.

Assuming again a 4.1 per cent cost of borrowing for the Commonwealth and given the original Future Fund’s one year return was 1.1 per cent, this equates to a 3.0 per cent — or approximately $6 billion — economic loss to the Commonwealth.

Comparing Apples with Apples

Comparisons of investment performance of the Future Funds viz-a-viz normal, non-government funds are also difficult. While it is correct that the financial performance of the Future Funds has been relatively strong compared to general investment funds, the Future Funds have three structural advantages.

- As government owned and operated funds, the Future Funds are exempt from income tax in Australia and benefit from sovereign tax immunity on most investments. Everything else equal, this gives the Future Fund an approximately 10 per cent performance advantage over other investment funds. This advantage will be further enhanced because the Albanese government intends to increase the tax rate on high balance superannuation accounts.

- The Future Funds are also not burdened with significant administration costs that ordinary superannuation funds must bear in managing members. The Future Funds have a single member each — the Commonwealth — whereas the top 10 superannuation funds collectively have approximately 15 million accounts that need to be managed. This is a significant cost, which erodes overall performance.

- The Future Funds are also not exposed to the same level of liquidity risk as are other funds. This is because they do not need to retain a proportion of funds in cash and other liquid assets to meet withdrawals from investment transfers and members moving into pension stage. This allows the Future Funds to invest a much higher proportion of portfolios into illiquid investments, such as infrastructure.

If, in the event of emergency, Future Fund investments needed to be quickly converted to cash, a significant liquidation cost would be imposed. Such an emergency event would likely be systemic, meaning that investments would need to be sold into falling markets further eroding value.. Even notionally liquid assets, such as listed securities and bonds, could be subject to a significant liquidation cost given the size of the Future Funds’ holdings.

These issues in and of themselves do not present the case against the Future Funds. However, with interest rates increasing and a more complex and volatile geostrategic and investing environment, the ability of the Future Fund to generate returns above its risk-adjusted cost of capital — or even its targeted rate of return — will be increasingly difficult.

Market Distortion

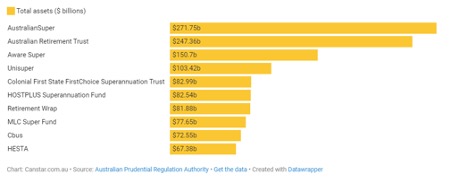

The Future Fund is one of the largest institutional investors in Australia. According to APRA data, the Future Funds’ assets under management would rank it as the second largest fund in Australia.

Source – Canstar and APRA

Much has been said and written about the disproportionate impacts large Australian superannuation funds might have on the governance of Australian businesses. Yet nary is there a word of the ability of the Commonwealth to exercise a similar influence. Granted there is a ‘firewall’ between the government and the Future Funds by way of the Board of Guardians, it is ultimately the government that appoints these Guardians and can indirectly effect influence through the choice of Guardians appointed. Personnel is, after all, policy.

Such a distortion might be a tolerable and necessary trade off were the Commonwealth budget in balance and the Commonwealth’s gross debt position closer to nil rather than closer to $1 trillion. Unfortunately, this is not the case resulting in the Future Funds, largely by virtue of their size, distorting the Australian investment market. This is particularly the case when the Future Funds benefit from the aforementioned tax and liquidity risk advantages. This results in a transfer of wealth from ordinary Australian savers to Commonwealth public servants.

Conclusion

The most recent Commonwealth budget forecast that the Commonwealth would have $923 billion of gross debt at the end of the 2024 financial year. Assuming a 4.1 per cent interest rate, the opportunity cost of this debt is approximately $38 billion. This is approximately the same amount that is spent on national defence.

According to economic historian Niall Ferguson, a sign of the impending collapse of an empire is when its debt costs exceed its defence costs. Beyond doubt, Australia is not an empire, but Australia’s debt position has the potential to become a national security matter as a greater proportion of national resources are spent on debt service. If the debt service costs of Australian states and territories are included, this picture looks much worse.

It is ironic that, in his response to Peter Costello’s 2005 second reading speech for the establishment of the original Future Fund, then shadow treasurer Wayne Swan said “Locking up the assets for the sole purpose of paying our bureaucrats’ super is like a family saving for a rainy day whilst the foundations in their house require severe repair work and remain unattended to. Failure to attend to them gets more costly year after year.” Using Swan’s metaphor, it’s raining debt and the Future Fund assets should be used to address that rather than meeting the costs of “our bureaucrats’ super”.

The Future Fund asset management ‘infrastructure’ has also grown beyond its original purpose to offset unfunded superannuation liabilities. It now manages several other funds for unrelated purposes. This includes the Medical Research Future Fund, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Land and Sea Future Fund, the Future Drought Fund, the Emergency Response Fund, and the Disability Care Australia Fund. And should Parliament pass it, the Housing Australia Future Fund.

If it is government policy to fund medical research, or to assist Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander citizens to acquire and manage land, or to build social housing, the government should directly and transparently fund such activities from the budget. Instead, what the government is doing is borrowing money, paying interest on these borrowings, and hoping that investment returns on these funds exceed the cost of borrowing.

There may have been a case for the Future Fund when the Commonwealth’s debt position was net negative. It may possibly have been the case for the Future Fund when interest rates were near zero.

But neither of those conditions hold any longer or are likely to reverse in the near to medium term. Meanwhile the opportunity cost of the debt is born by the budget and the benefits accrue to the funds. If public finance was as simple as borrowing money, investing, and spending the profit above the cost of interest, the Commonwealth should just borrow $10 trillion, invest it, and eliminate all taxes.

By closing the Future Fund and retiring debt, the Commonwealth will have a lower interest expense in the budget and Australian citizens will have a much clearer and transparent view as to where public spending is going and the state of the Commonwealth’s balance sheet.

A future without the Future Fund is a more viable one.