Australians are conflicted in their attitude to this long-run change in real house prices because they are both investors in housing as an asset class and consumers of housing services. This conflicted attitude on the part of the public is reflected in confused public policies followed by Australian governments. Unfortunately, many of the policies pursued by Australian governments in the name of housing affordability, such as first home buyer grants and concessions, increase demand for housing, while failing to tackle regulatory and cost barriers to housing supply. Some policy proposals for improving housing affordability focus on demand suppression and diversion rather than augmenting housing supply. This reflects a failure to understand the relationship of these policies to the overall supply and demand for housing. However, it also reflects a number of highly persistent myths about the nature of housing markets, the dynamics of house prices, and the drivers of housing affordability that in turn condition public policy. This report seeks to tackle these myths in an effort to improve the quality of public debate about housing affordability.

Myth 1: Lower interest rates make housing more affordable

Myth 2: House prices are a speculative ‘bubble’

Myth 3: The supply of land is fixed

Myth 4: Housing is an unproductive asset

Myth 5: Australians invest too much in housing

Myth 6: Foreign investors are responsible for rising house prices

Myth 7: Domestic investors/negative gearing/capital gains tax concessions are responsible for rising house prices

Myth 8: House prices are fuelled by a credit ‘bubble’/excessive leverage

Executive Summary

- Australia has experienced a significant increase in house prices in recent decades.

- House prices have increased at an average rate of about 3% per annum after inflation since 1970.

- Australians are conflicted in their attitude to this long-run change in real house prices because they are both investors in housing as an asset class and consumers of housing services.

- Homeownership in Australia has declined in recent years from 71% of households in 1995 to 67% in 2012, with even more pronounced falls in younger age groups most likely to be first home buyers.

- The conflicted attitude on the part of the public is reflected in confused public policies followed by Australian governments, often in the name of housing affordability.

- Housing consumption and investment are both taxed and subsidised by all levels of government.

- The net effect of these taxes and subsidies on housing affordability is difficult to determine.

- Many of the policies pursued by Australian governments in the name of housing affordability, such as first home buyer grants and concessions, increase demand for housing, while failing to tackle regulatory and cost barriers to housing supply.

- Declining real interest rates boost asset prices by lowering the discount rate applied to future income streams—or (imputed) rents in the case of housing.

- Lower interest rates have also increased the debt servicing capacity of households.

- The reduction in real mortgage interest rates has been a secular rather than a cyclical phenomenon, leading to permanent rather than temporary gains in house prices, although this secular trend could be reversed, at least in principle.

- In the long run, real interest rates and housing affordability are determined by factors outside the control of monetary policy.

- The reductions in real mortgage interest rates and increased competition and innovation in financial services that have increased household leverage relative to earlier decades have been a secular rather than a cyclical phenomenon. The associated gains in house prices are unlikely to be reversed.

- In Australia, the long-run appreciation of real house prices, as well as their short-run variability, is empirically well explained by economic fundamentals and is entirely consistent with expectations derived from economic theory.

- Australia is not producing enough new land for housing due to policies pursued by state and local governments that prevent land supply and land use from responding to price signals.

- Housing supply must keep pace not only with population growth and the rate of new household formation, but also the demolition of old homes and the demand for second or holiday homes.

- If temporary residents are not allowed to purchase dwellings, they will enter the private rental market and reduce affordability in that market.

- When foreigners buy domestic property, they transfer overseas wealth to Australians in the form of either new dwellings or higher prices for existing dwellings.

- The concessional tax treatment of saving via owner-occupied and investment property adds to demand by making both a more attractive vehicle for saving relative to other asset classes. It is also positive for housing supply by making investment in housing more attractive. The net effect on dwelling prices is ambiguous and there is a lack of empirical work on this question.

- The focus of public policy needs to shift to lowering tax and regulatory barriers to new dwelling supply.

- Reducing the incidence or eliminating entirely taxes on housing transactions such as stamp duty and capital gains tax should be an important part of any broader tax reform effort and reform of federal-state financial relations.

- Zoning, planning and approval processes need to be reformed to reduce the direct and indirect costs of new dwelling construction, increase the intensity of land use, and accelerate new land release.

Introduction

Along with many other countries, Australia has experienced a significant increase in house prices in recent decades. House prices have increased at an average rate of about 3% per annum after inflation since 1970. Australians are conflicted in their attitude to this long-run change in real house prices because they are both investors in housing as an asset class and consumers of housing services. On the one hand, rising real house prices yield an increase in real wealth for the 67% of Australian households who are owner-occupiers.i On the other hand, rising house prices represent a reduction in purchasing power over housing services for those who do not already own housing, as well as owner-occupiers who would like to increase their consumption of housing services, for example, through the acquisition of a larger, better quality or more conveniently located home. Homeownership in Australia has declined from 71% of households in 1995 to 67% in 2012, with even more pronounced falls in younger age groups most likely to be first home buyers.ii This may be partly due to a decline in housing affordability, but could also be due to changing preferences over housing.

The conflicted attitude on the part of the public is reflected in confused public policies followed by Australian governments, often in the name of housing affordability. Housing consumption and investment are both taxed and subsidised by all levels of government. The net effect of these taxes and subsidies on housing affordability is difficult to determine as it depends on the benchmarks used to determine what is taxed and what is subsidised.iii For example, is the failure to tax imputed rent on the part of owner-occupiers a subsidy? Does the principal residence exemption from capital gains tax constitute a subsidy? The answers to these questions depend entirely on the benchmark tax system used, which is itself subject to debate. The ambiguous net effects of taxes and subsidies on housing affordability are useful to politicians, who can pretend to be assisting home buyers and renters on the one hand, while still exploiting housing as a tax base on the other. The complex system of housing taxes and subsidies allows politicians to avoid accountability for the effects of their policies.

The long-run increase in real house prices is conceptually easy to explain as an increase in demand for housing on the part of owner-occupiers and investors relative to the supply of housing, which includes the stock of existing dwellings as well as additions to that stock in the form of newly built homes. Policies that increase the demand for housing will tend to increase house prices, while policies that lead to an increase in supply will tend to lower prices, all else being equal. For example, a 1% increase in the stock of housing per capita will lower real house prices by 3.6% on average based on historical experience in Australia.iv This simple supply-and-demand framework provides a conceptually clear basis for evaluating public policies relating to housing affordability.

Unfortunately, many of the policies pursued by Australian governments in the name of housing affordability, such as first home buyer grants and concessions, increase demand for housing, while failing to tackle regulatory and cost barriers to housing supply. Some policy proposals for improving housing affordability focus on demand suppression and diversion rather than augmenting housing supply. This reflects a failure to understand the relationship of these policies to the conceptual framework outlined above. However, it also reflects a number of highly persistent myths about the nature of housing markets, the dynamics of house prices and the drivers of housing affordability that in turn condition public policy. This report seeks to tackle these myths in an effort to improve the quality of public debate about housing affordability.

Myth 1: Lower interest rates make housing more affordable

Housing affordability is a relative rather than an absolute concept and there is no unique way of measuring housing affordability. A commonly used measure is the ratio of median or average house prices to median or average wages or household income. However, the buyer of the median house is not necessarily a median income earner. The distribution of house prices and household incomes can shift for reasons unrelated to changes in housing affordability. These measures often fail to take account of changes in the size of houses or households. They do not consider rents, which are an important determinant of housing affordability for non-owner-occupiers. These measures also do not take account of the real cost of housing finance.

A second approach considers the ratio of housing costs (including mortgage interest or rents) to household income. This measure is sometimes used to benchmark ‘housing stress.’ For example, it is commonly asserted that housing costs in excess of 30% of income are indicative of housing stress. This is a flawed benchmark in that higher income households could spend more than 30% of their incomes on mortgage interest or rent while still being able to fund a high standard of living. Some households may choose to spend more on housing to economise on commuting time and other costs that are not included in these measures of housing affordability. ‘Housing stress’ is usually a low income problem rather than a housing affordability problem, requiring a different set of public policy responses.

A third approach considers the ratio of mortgage repayments (interest and principal) relative to incomes. This in turn requires appropriate definitions of a ‘standard’ mortgage, but this is only likely to be meaningful to the 37% of households that are owner-occupiers with a mortgage. These measures are based on nominal rather than real interest rates. This is misleading in that nominal interest rates reflect an inflation premium that is also reflected in appreciation of nominal house prices. Repayments of principal are a form of saving rather than a cost of housing. For this reason, mortgage repayments are not included in the Consumer Price Index (CPI), although some related costs of financial intermediation are included. These measures of housing affordability show a great deal of short-term cyclical variability due to changes in nominal interest rates. Changes in nominal borrowing rates will reflect changes in inflation and official interest rates, but this variability is not very informative about changes in long-run housing affordability. Over the life of a typical home loan, borrowers will experience the full range of the cycle in nominal interest rates. Real interest rates show less variability and home buyers will pay the average real interest rate on their mortgage regardless of when they buy into the interest rate cycle. In the long run, monetary policy is neutral with respect to the real economy and does not determine the supply and demand for housing or housing affordability.

A fourth approach to measuring housing affordability is in terms of real user costs. This is the cost of occupying as opposed to buying a dwelling. Equivalently, this can be thought of in terms of opportunity cost or the goods and services forgone to occupy the dwelling. The real user cost of housing can be defined as real interest payments (including the opportunity cost of the owner’s equity), maintenance expenses, land and property taxes such as council rates, less any change in real house prices. Repayments of principal on a mortgage are a form of saving rather than a cost. For renters, dwelling rents are an adequate proxy for the user cost of housing on the assumption the landlord bears other costs. The real user cost approach implies that the expected annual cost of owning a house should not exceed the annual cost of renting, at least in equilibrium. However, substitution between owner-occupation and the rental market is limited by the high costs of buying and selling and moving. It is not surprising then that the user cost of housing for owner-occupiers may deviate from rental costs. The user cost approach also implies that house price-to-income and house price-to-rent ratios may not be reliable as measures of housing values and housing affordability.v

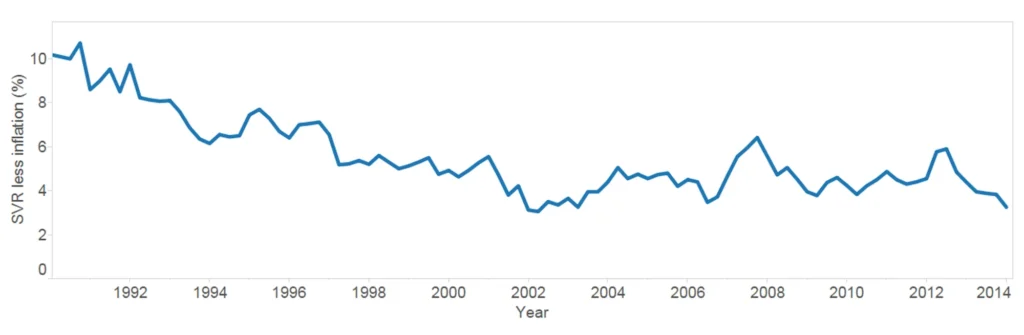

Global real interest rates have declined over the last 30 years. As Australian borrowing rates are largely determined overseas, real mortgage interest rates in Australia have also declined. From around 10% in 1990, the real standard variable mortgage interest rate has declined to a little more than 3% at the end of 2013 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Standard variable mortgage interest rate less inflation (%)

Source: Reserve Bank of Australia. Inflation rate has been adjusted for changes in taxes.

Declining real interest rates boost asset prices by lowering the discount rate applied to future income streams or (imputed) rents in the case of housing. Lower interest rates have also increased the debt servicing capacity of households. Borrowers can now take on larger loans without necessarily having to pay more in terms of interest. Together with increased competition and new innovations in housing finance, this saw an increase in the ratio of household debt to household incomes and house prices to incomes from around the mid-1980s through to the early 2000s, stabilising around 2005. This in turn put upward pressure on dwelling prices, but only because housing supply has not been sufficiently flexible to accommodate the increase in demand due to increased household borrowing capacity and leverage. Had the supply side of housing markets been more flexible, lower real interest rates would have had a less pronounced impact on house prices.

Peter Abelson, Roselyn Joyeux, and George Milunovich estimate that a 1% decline in real mortgage interest rates will raise house prices by 5.4% in the long run.vi Glenn Otto finds an effect of similar magnitude of 4% and confirms that it is the real and not the inflation component of nominal interest rates that matters.vii The sensitivity of house prices to changes in interest rates is higher when interest rates are low because a given percentage point change in interest rates yields a larger percentage reduction in the user cost of housing. Sensitivity also increases when expected price growth is high.viii

The reduction in real mortgage interest rates has been a secular rather than a cyclical phenomenon, leading to permanent rather than temporary gains in house prices, although this secular trend could be reversed, at least in principle. It has also been a global development and not one confined to Australia. Calls for lower mortgage interest rates via easier monetary policy to promote housing affordability are thus misplaced. In the long run, real interest rates and housing affordability are determined by factors outside the control of monetary policy.

Myth 2: House prices are a speculative ‘bubble’

An asset price ‘bubble’ has no widely accepted definition and the term ‘bubble’ is largely empty of empirical or analytical content. The term is generally used to suggest a market price that is disconnected from fundamentals, perhaps because of ‘irrational’ investor psychology or self-fulfilling expectations. This does not help explain changes in asset prices, since it still leaves changes in investor psychology or expectations without any explanation. When pushed, most commentators who assert that an asset class is experiencing a price ‘bubble’ will fall back on fundamental explanations, rendering the ‘bubble’ characterisation redundant.ix

In Australia, the long-run appreciation of real house prices, as well as their short-run variability, is empirically well explained by economic fundamentals and is entirely consistent with expectations derived from economic theory.x Australia has enjoyed strong growth in incomes and population, lower real mortgage interest rates (see Myth 1), and innovations in financial intermediation and housing finance that have all driven increases in demand. At the same time, the supply of new housing has been limited by planning and development controls, as detailed elsewhere in this report. This provides the fundamental basis for long-term increases in real house prices.

House prices exhibit pronounced cycles, not least because housing demand responds more quickly to changing economic conditions than does housing supply. In particular, the price elasticity of demand for housing is generally thought to be equal to one, yielding a proportionate relationship between dwelling prices and dwelling demand. The price elasticity of supply by contrast is thought to be below one, especially in the short run, when regulation is a binding constraint on new supply.xi The supply of new land and new housing is largely determined by development and planning controls rather than market-generated price signals.

Much commentary on housing markets focuses on dramatic short-term changes in house prices, failing to put these changes in longer-term context. For example, Sydney house prices increased by 15.6% in nominal terms over the year to March 2014. While this sounds dramatic, it follows a decade of subdued price growth that is even less pronounced in real terms. After inflation, Sydney house prices have increased by only 0.4% over the last decade.xii Over the last 15 years, Sydney house prices have increased a little over 3%,xiii consistent with the nationwide trend growth rate in real house prices seen since the 1970s. Melbourne has shown stronger gains than Sydney (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Real growth in house prices, periods ending March 2014

Source: RP Data.

It should be recalled that because Australia has institutionalised a higher rate of consumer price inflation via a higher central bank inflation target than many comparable economies, Australia’s nominal rate of house price inflation will on average be higher than in other economies, all else being equal. This gives the impression that house prices in Australia are growing faster than in other countries, but differences in growth rates are less pronounced when comparisons are made in real terms.

Real house prices in Australia rose at an average rate of 3% between 1970 and 2003. Adjusting for changes in housing quality, prices increased by 2.3% per annum in real terms between 1970 and 2003, a growth rate sufficient to yield a doubling of house prices over the same period.xiv Since 2003, quality-adjusted real house prices for Australia’s eight capital cities have risen at an average rate of 3%. These averages conceal considerable short-run cyclical variation, but the underlying trend for housing affordability can only be ascertained by looking through these short-term cycles. The cycle in house prices around this long-run trend growth rate is not a ‘bubble’—it is well explained by fundamentals. The long-run trend is nonetheless a problem in terms of deteriorating housing affordability.

The belief that house prices are driven by irrational investors rather than economic fundamentals leads to the promotion of demand-suppression and demand-diversion policies rather than policies that augment housing supply. Examples of demand-suppression policies include quantitative restrictions on lending for housing (also known as macroprudential regulation) or central banks using their control over official interest rates to ‘prick’ housing ‘bubbles.’ These policies cannot improve housing affordability in the long run. Quantitative controls on lending for housing may change the composition of owner-occupiers and the balance between owner-occupiers and renters, but are unlikely to improve the imbalances in housing supply and demand that drive long-run increases in prices and rents. Monetary policy is neutral in the long run and cannot change these determinants of real house prices.

It is also meaningless to assert that house prices are driven by ‘speculation.’ Few people buy or invest in housing with the expectation of making a capital loss. In that sense, every decision to buy (or not to buy) property is speculative. As Ludwig von Mises observed, ‘Every action is a speculation, i.e., guided by a definite opinion concerning the uncertain conditions of the future.’xv The belief that housing markets are driven by ‘speculation’ misunderstands the role of speculation in an economy and encourages the pursuit of demand-suppression and diversion policies on the basis that prices are disconnected from fundamentals.

Myth 3: The supply of land is fixed

The supply of land is finite in a physical sense, but not in an economic sense. Especially in Australia, land supply is far from exhausted and the intensity of existing land use can always be increased. The supply of land is a constraint on the supply side of the housing market in the short run, but it should not be a constraint in the long run if land supply and land use are allowed to respond to price signals from housing markets. Rising land and house prices should call forth increased land supply and increase the intensity of land use, putting downward pressure on prices.

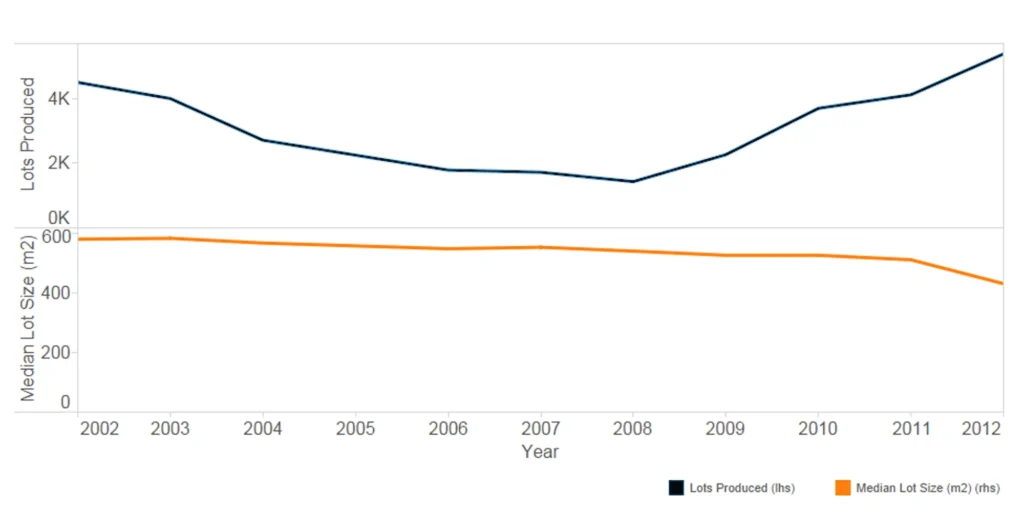

Unfortunately, Australia is not producing enough new land for housing due to policies pursued by state and local governments that prevent land supply and land use from responding to price signals. In fact, the supply of new land for housing has declined over the last decade, with the average number of lots produced in the five largest capital cities declining by 21%. The decrease in the supply of new land has not surprisingly seen an increase in land prices. The median price of land for new home buyers in the five largest capital cities is an average $504 per square metre, an increase of 148% over the last decade (compared to consumer price inflation of around 30% over the same period). Higher prices have seen a reduction in lot sizes as home buyers seek to economise on housing costs, meaning new home buyers pay a higher price per square metre. The median new lot size across the five largest capital cities is an average 423 metres, a contraction of 29% over the last decade.xvi The increase in the intensity of land use may be viewed as a positive for housing supply and affordability, although some councils are opposed to small lot housing.

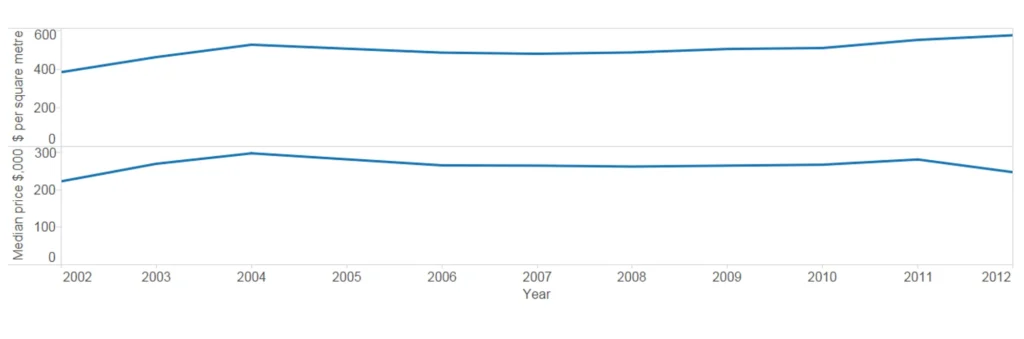

Sydney housing lot production and prices are shown in figures 3 and 4 below. The price of land for new housing has increased from $385 to $576 per square metre since 2003, a 50% increase.

Figure 3: Sydney land supply, quantity

Source: Urban Development Institute of Australia.

Figure 4: Sydney land supply, price

Source: Urban Development Institute of Australia.

The figures show the reduction in the supply of new lots during the early to mid-2000s, decreasing lot size, and rising prices per square metre.

The long-run increase in the price of new land for housing is indicative of the failure of state governments to increase land supply to accommodate rising demand for new housing. This in turn flows through to land values for existing housing. State governments can promote housing affordability by increasing the supply of lots for new housing. State and local governments can also contribute to an increase in the intensity of land use through zoning and planning reform. Both greenfield and in-fill developments should be encouraged. The belief that the supply of land is somehow fixed diverts attention from these policy options.

Myth 4: Housing is an unproductive asset

It is frequently asserted that housing is an unproductive asset. Housing is productive in meeting the fundamental human need for shelter. Housing thus provides a stream of valuable services that can be directly valued by (imputed) rental yields. Capital city houses had gross rental yields of 3.8% in March 2014, while units had gross rental yields of 4.6%.xvii Housing competes with other asset classes in providing a return to investors. If housing were unproductive, it could not compete with other asset classes in providing a positive long-run real rate of return. The view that housing is somehow unproductive rather than providing a fundamentally important and valuable service helps rationalise the underproduction of new housing and encourages policymakers to ignore supply-side policies to improve housing affordability.

A related view is that the returns to housing are attributable to rents on land. Restrictions on land supply do create rents that accrue to existing property owners, but this is a function of those restrictions. As noted previously, there is no reason in principle why land scarcities should drive long-run increases in real house prices, given sufficient flexibility in the supply of new land and land use. Economic rents may arise from the non-reproducible attributes of some specific locations (e.g. harbour views), but not from land in general. The returns to real estate thus need not reflect above-normal returns or economic rents, although restrictions on the supply of new land have created rents in practice. The belief that real gains in house prices reflect rents derived from land encourages the view that housing is unproductive. It also encourages the view that saving via housing can be taxed via capital gains or wealth taxes without adverse implications for dwelling supply.

Myth 5: Australians invest too much in housing

The view that housing is an ‘unproductive’ asset promotes the related myth that Australians invest too much in housing. This claim is difficult to reconcile with rising house prices. Australians spend more on housing than would be the case if supply kept pace with demand. But for supply to increase requires that we invest more in new housing in real terms, not less. Housing supply must keep pace not only with population growth and the rate of new household formation, but also the demolition of old homes and the demand for second or holiday homes. As incomes rise, Australians will also demand improvements in the quality and size of new homes. The average dwelling size has increased from 2.9 to 3.1 bedrooms since 1995, while average household size has decreased from 2.7 to 2.6 persons over the same period.xviii As former RBA Deputy Governor Ric Battellino has observed, ‘The overall amount of dwelling investment undertaken will need to increase relative to GDP.’xix

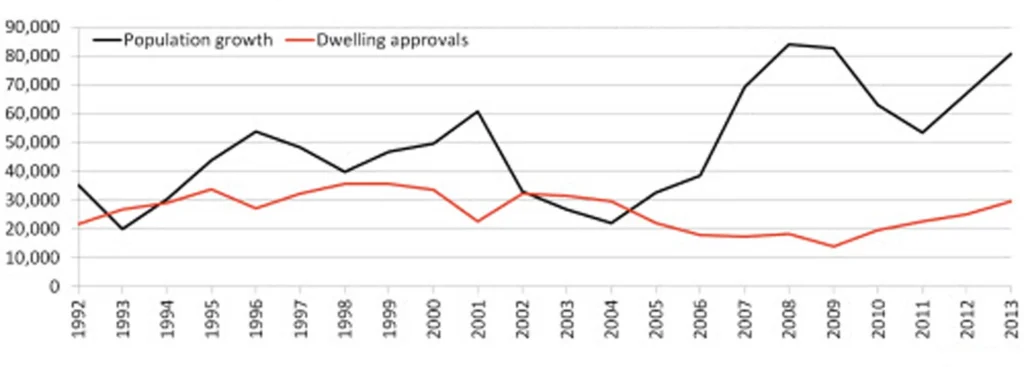

New dwelling supply in Australia has fallen behind population growth in recent years. As Saul Eslake notes, the last decade is the first since World War II when the housing stock grew at a slower rate than the population.xx A simple benchmark for the adequacy of new housing supply is to consider the relationship between dwelling approvals and population growth. In the year to June 2013, new dwelling approvals by local government ran at a rate of one new dwelling for every 2.73 residents. Average household size in the 2011 Census was 2.6 persons per household, giving a shortfall in dwelling approvals even if no allowance is made for demolition of older homes and demand for second homes. The ratio of population growth to dwelling approvals has increased in the 2000s, particularly in Sydney (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Annual population growth vs annual dwelling approvals, Sydney

Source: RP Data, http://blog.rpdata.com/2014/04/capital-city-population-booming-capital-city-supply-side-response-dismal/

Myth 6: Foreign investors are responsible for rising house prices

Rising house prices are sometimes attributed to foreign investor demand, with the implication that foreigners should be further restricted from investing in Australian real estate. Foreigners are currently restricted from buying established housing and need Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) approval for purchases of new dwellings. Special rules also apply to temporary residents. If temporary residents are not allowed to purchase dwellings, they will enter the private rental market and reduce affordability in that market. It is government policy to attract temporary residents in the form of international students and skilled workers. Preventing these temporary residents from purchasing homes undermines the success of these policies.

The rationale for these restrictions on foreign buyers is to channel foreign investor demand for real estate into new construction. However, this still creates indirect competition for established dwellings because local buyers are potentially displaced from the market for new dwellings. Comparisons of FIRB approvals for investment in real estate with total residential sales suggest foreign buyers account for only around 2–3% of total market demand in volume terms, although foreign demand is likely to be concentrated in specific locations and property types. It is also important to recognise that FIRB approvals only capture gross and not net demand. There is no attempt made to track subsequent re-sales by foreign investors to local buyers.

The existing rules are almost certainly flaunted because the FIRB is under-resourced for the task of policing thousands of real estate transactions. The inability to enforce the current rules at a reasonable cost to the taxpayer is itself a strong argument for doing away with these restrictions on foreign direct investment in real estate. This would put Australia on the same footing as comparable countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom, which do not restrict foreigners from buying local real estate. This open-door policy in relation to foreign direct investment in real estate almost certainly contributes to higher house prices in places like London that are attractive to foreign investors. However, this is entirely attributable to the inability of the supply side to accommodate both domestic and foreign demand. It is not a problem with foreign demand as such.

New dwelling construction responds to overall demand, not just demand from foreign investors. Whether this demand is accommodated through increased supply or rising prices is not a function of where the demand comes from, but the costs embedded in the supply side of the housing market. The House of Representatives Economics Committee has established an inquiry into the existing rules for foreign investors. According to Committee chair Kelly O’Dwyer, the inquiry will consider whether the current restrictions on foreign investment in residential real estate serve to increase supply, as is their stated intention, or raise prices. This is rather like asking whether foreign tourists increase the production of goods and services or raise consumer prices. The answer depends on how flexibly Australian producers can accommodate changes in foreign as well as local demand through increased output.

It is pointless blaming foreigners for inflexibilities in the supply side of the Australian economy. For that, we should blame local politicians. If politicians are concerned about housing affordability, they should examine the tax and regulatory burdens their policies place on new housing supply rather than seeking to make scapegoats out of the foreign and local investors who supply much of the capital that funds new dwelling construction. Pre-sales to foreign investors are an important element of the financing of new apartment construction.

When foreigners buy domestic property, they transfer overseas wealth to Australians in the form of either new dwellings or higher prices for existing dwellings. In the first instance, these wealth transfers will likely be to property developers building specifically for foreign and domestic investors. Once built, the property is available for rent or subsequent purchase in the secondary market. The developers’ profits can be used to fund further investment in housing.

Concerns have been raised that some foreign buyers leave property vacant. But they are no different in this regard from many local property investors. It is often rational to leave property vacant when prospective capital gains provide a sufficient return on the investment. This too is a function of the supply-side constraints Australian politicians have inflicted on property markets. Similarly, land banking is often a rational response to development controls that make new development too costly. The 2011 Census shows that 10.7% of the privately owned dwelling stock is unoccupied.xxi Many of these properties will be second homes outside capital cities. The existence of unoccupied dwellings, whether owned by locals or foreigners, does not in any way contradict the argument that there is a shortage of dwelling stock. In fact, it is entirely consistent with it.

The government’s existing foreign investment policy goes so far as to suggest that ‘some types of investment in real estate are contrary to the national interest.’xxii The existing controls over foreign investment in real estate serve no purpose other than to propagate the myth that Australia is somehow worse off because foreigners want to add to the stock of real estate and national wealth. Restrictions on foreign ownership of real estate should be removed in conjunction with policies to free up the supply side of the housing market.

Myth 7: Domestic investors/negative gearing/capital gains tax concessions are responsible for rising house prices

A fundamental principle of economics is that if you tax something more heavily, you will get less of it. This principle is well understood in relation to markets in goods and services, but is often forgotten in relation to housing. Many people suppose that housing affordability can be improved by making investment in housing less attractive via the tax system, thereby reducing investor demand and benefiting owner-occupiers, including first home buyers. But this assumes that the effects of these policies can be quarantined to the demand side of the market and have no implications for dwelling supply.

The deductibility of mortgage interest against other income for investments in housing is first and foremost an issue of tax policy. Housing is not the only asset class for which interest on borrowing to invest is deductable against other income, and so negative gearing cannot be considered a tax concession or subsidy for housing. It is debateable whether negative gearing is a tax expenditure.

There are legitimate questions over how the tax system treats income derived from saving and investment, including rental income. It is widely acknowledged that the tax system heavily taxes some forms of saving (for example, interest on saving deposits), while only lightly taxing or rewarding others (for example, concessional superannuation contributions). Ideally, the tax system would more equally reward all forms of saving and investment to encourage capital accumulation, including much needed additions to the housing stock to accommodate a growing population. The Henry review argued for a more consistent treatment of income derived from saving, which would have seen a 40% discount applied to the taxation of capital gains, interest and net rental income. This proposal was a somewhat less generous, but still ‘concessional’ (depending on the benchmark used), treatment of investment income derived from property, consistent with the review’s objective of reducing the overall tax burden on saving.

However, the Henry review was explicit about the need to free up the supply side of the housing market before any such reform was attempted. Henry’s final reported noted:

Changing the taxation of investment properties could have an adverse impact in the short to medium term on the housing market … reducing net rental losses and capital gains tax concessions may in the short-term reduce residential property investment. In a market facing supply constraints, these reforms could place further pressure on the availability of affordable rental accommodation.xxiii

Other proposals for making the tax treatment of investment property less generous include quarantining deductibility to income derived from the investment only or requiring losses to be carried forward to offset future capital gains tax liabilities. For example, Saul Eslake supports the latter option.xxiv The concessional tax treatment of saving via owner-occupied and investment property adds to demand by making both a more attractive vehicle for saving relative to other asset classes. It is also positive for housing supply by making investment in housing more attractive. The net effect on dwelling prices is ambiguous and there is a lack of empirical work on this question.

It is sometimes noted that demand from property investors is largely met through existing rather than newly built dwellings. This reflects the fact that the flow of new houses is small relative to the existing dwelling stock. Annual dwelling completions average around 2% of the housing stock.xxv But it is about as relevant as noting that investors in the stock market mostly buy existing equity rather than newly issued shares. It is only supply-side constraints that prevent demand for existing dwellings from inducing new construction. In fact, housing subsidies can help reduce the economic inefficiency that results from the regulation of new housing supply, although the first-best public policy solution is to deregulate housing supply.xxvi

The short- to medium-term impact on the rental market from less generous tax treatment of investment property highlighted by the Henry review could be mitigated to the extent that any fall in prices induces more renters to become owner-occupiers. However, substitution between investors and owner-occupiers is unlikely to offer much relief in terms of overall housing affordability, especially if there is also a negative supply response in the rental market.

Public policy should aim to improve incentives for increasing housing supply. Saving via housing is concessionally taxed due to the principal residence exemption for owner-occupiers and the capital gains tax discount for investors of more than 12 months. However, it should be noted that because capital gains tax is now levied on nominal rather than real gains, capital gains are no longer concessionally taxed to the extent that the inflation rate exceeds the growth rate in real house prices. The capital gains tax discount for investors also lowers the value of the principal residence exemption to owner-occupiers.

The concessional tax treatment of saving via housing does not mean there is no tax burden on housing as such. The tax burden on new housing includes direct taxes such as the goods and services tax, stamp duty, land tax, and council rates, as well as a variety of indirect taxes on inputs into housing, development and infrastructure levies. There are also hidden taxes from unnecessarily complex and expensive planning and approval processes. The Centre for International Economics has estimated that as much as 44% of the price of a new home in Sydney is accounted for by explicit and implicit local, state and federal taxes.xxvii

The animus directed against negative gearing is as much an objection to the tax deduction as its supposed implications for housing affordability. Few people seem to object to an investor buying a property outright or having rental income in excess of deductions, making them a net taxpayer in relation to the investment.

Those who negatively gear into property ultimately rely on taxable capital gains to make up for net losses on rental income incurred over the life of the investment. Unless capital gains exceed borrowing and other costs, negative gearing is a losing investment strategy. Like all leveraged investments, negative gearing is risky, not a one-way bet. Property investors specialise in bearing market risks that many owner-occupiers and renters are either unwilling or unable to take. Reducing incentives for risk-bearing through the tax system will adversely effect the supply side of the housing market, as well as reduce demand, with uncertain implications for house prices and housing affordability.

Myth 8: House prices are fuelled by a credit ‘bubble’/excessive leverage

Australian governments pursued financial repression policies up until the mid-1980s that were designed to suppress price signals in financial markets and to monetise the debts of the Commonwealth government.xxviii These policies included regulated price ceilings for mortgage and other interest rates, quantitative lending controls, and extensive credit rationing.

With the onset of financial deregulation from the mid-1980s, households were able to pursue a more optimal mix of consumption and saving and increase their leverage. Falling real interest rates and increased competition in financial services increased the capacity of households to borrow. This is reflected in higher house prices, but only because supply constraints prevented increased debt servicing capacity—and the associated demand for housing being accommodated through new dwelling construction.

While previous house price cycles have been associated with increases in housing credit and household debt relative to income, the same cannot be said of the most recent boom. Housing credit growth has been on a declining trend for a decade, although it has picked up more recently. The ratio of household debt to household income has stabilised since 2005 at around 150%. Repayments on new housing loans as a percentage of disposable income are below previous historical peaks. Mortgage arrears are at low levels.xxix The reductions in real mortgage interest rates and increased competition and innovation in financial services that have increased household leverage relative to earlier decades have been a secular rather than a cyclical phenomenon. The associated gains in house prices are unlikely to be reversed. Even if the supply side of housing markets were significantly liberalised, market-determined price signals should prevent the emergence of significant over-supply in the long run. Recent gains in house prices have been driven by fundamentals rather than excessive leverage.

Conclusion

The debate over housing affordability is often conducted in zero-sum terms. First home buyers are pitted against investors and incumbent property owners, baby boomers against younger age groups. The implicit assumption is that there is fixed housing stock to be carved up among these competing interests. In principle, the housing market should be able to accommodate increasing demand without upward pressure on prices. In reality, the supply side of the housing market has been taxed and regulated to the point that supply has not been able to keep pace with demand, leading to higher house prices. Rising real house prices have become a secular phenomenon, with the cyclical variation in house prices taking place around this rising trend.

Each of the housing affordability myths reviewed and debunked here serves to distract public policy from an increased focus on improving housing supply. As Abelson notes:

Housing affordability is essentially a household income problem made worse by government restrictions on housing supply. The housing market has few market failure features. This is not simply an academic debate about the nature of market failures. It has fundamental practical policy implications.xxx

The focus of public policy needs to shift to lowering tax and regulatory barriers to new dwelling supply. Reducing the incidence or eliminating entirely taxes on housing transactions such as stamp duty and capital gains tax should be an important part of any broader tax reform effort and reform of federal-state financial relations. Zoning, planning and approval processes need to be reformed to reduce the direct and indirect costs of new dwelling construction, increase the intensity of land use, and accelerate new land release.

Public policy should also avoid demand-side policies, such as financial assistance to first home owners or allowing access to superannuation account balances for the purposes of buying a home. The most effective way of increasing housing affordability for first home and other buyers and renters is to ensure a plentiful supply of new dwellings to reduce upward pressure on prices.

References

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics), Housing Occupancy and Costs, 2011–12, Cat. No. 4130 (Canberra: ABS, 28 August 2013).

Peter Abelson and Roselyn Joyeux, ‘Price and Efficiency Effects of Taxes and Subsidies for Australian Housing,’ Economic Papers 26:2 (June 2007).

Peter Abelson, Roselyn Joyeux, and George Milunovich, ‘Explaining House Prices in Australia: 1970–2003,’ Economic Record 81:Special Issue (August 2005), S100.

Charles Himmelberg, Christopher Mayer, and Todd Sinai, ‘Assessing High House Prices: Bubbles, Fundamentals and Misperceptions,’ Journal of Economic Perspectives 19:4 (Fall 2005): 68.

Peter Abelson, Roselyn Joyeux, and George Milunovich, ‘Explaining House Prices in Australia: 1970–2003,’ as above, S100.

Glenn Otto, ‘The Growth of House Prices in Australian Capital Cities: What Do Economic Fundamentals Explain?’ The Australian Economic Review 40:3 (2007).

Charles Himmelberg, Christopher Mayer, and Todd Sinai, ‘Assessing High House Prices: Bubbles, Fundamentals and Misperceptions,’ as above, 68.

Stephen Kirchner, Bubble Poppers: Monetary Policy and the Myth of Bubbles in Asset Prices, Policy Monograph 93 (Sydney: The Centre for Independent Studies, March 2009).

Peter Abelson, Roselyn Joyeux, and George Milunovich, ‘Explaining House Prices in Australia: 1970–2003’; Glenn Otto, ‘The Growth of House Prices in Australian Capital Cities,’ as above.

Peter Abelson and Roselyn Joyeux, ‘Price and Efficiency Effects of Taxes and Subsidies for Australian Housing,’ as above, 159.

RP Data-Rismark March Hedonic Home Value Index Results (1 April 2014).

Cameron Kusher, Inflation Remains Contained within the RBA’s Target Range, RP Data Research Blog (23 April 2014), http://blog.rpdata.com/2014/04/inflation-remains-contained-within-rbas-target-range/.

Peter Abelson, Roselyn Joyeux, and George Milunovich, ‘Explaining House Prices in Australia: 1970–2003,’ as above, S97.

Ludwig von Mises, The Ultimate Foundation of Economic Science: An Essay on Method (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2006), 51.

Urban Development Institute of Australia, The 2014 UDIA State of the Land Report (Canberra: Urban Development Institute of Australia, 2014), 3.

RP Data-Rismark March Hedonic Home Value Index Results.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics), Housing Occupancy and Costs, 2011–12, as above, 4.

Ric Battellino, ‘Housing and the Economy,’ Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin (December 2009), 39.

Saul Eslake, 50 Years of Housing Failure, Speech to the 122nd Annual Henry George Commemorative Dinner (2 September 2013).

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics), 2011 Census QuickStats, www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2011/quickstat/0

Australian Treasury, Australia’s Foreign Investment Policy (includes the ‘Policy Statement: Foreign Investment in Agriculture’) (2013), http://www.firb.gov.au/content/policy.asp.

Commonwealth of Australia, Australia’s Future Tax System (the Henry review) (Canberra: 2010).

Saul Eslake, 50 Years of Housing Failure, as above.

Peter Abelson, Roselyn Joyeux, and George Milunovich, ‘Explaining House Prices in Australia: 1970–2003,’ as above, S97.

The efficiency gain from the subsidy arises where the housing market marginal cost curve is below the market price that reflects the regulation of new housing supply (see Peter Abelson and Roselyn Joyeux, ‘Price and Efficiency Effects of Taxes and Subsidies for Australian Housing,’ as above, 164).

Centre for International Economics, Taxation of the Housing Sector (Sydney: 2012).

Carmen Reinhart and Jacob Kirkegaard, The Return of Financial Repression in the Aftermath of the Great Contraction (Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2012).

Reserve Bank of Australia, Economic Group, Financial Stability Review (Sydney: March 2014).

Peter Abelson, ‘Affordable Housing: Concepts and Policies,’ Economic Papers 28:1 (March 2009), 27–28.