1. Executive Summary

The Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (Standards) do not adequately outline what teachers should know and be able to do, and are neutral as to what constitutes effective practice. As such, they are in urgent need of reform.

These reforms should be conducted in parallel with adoption of recommendations of the Strong Beginnings report of the Teacher Education Expert Panel. For example, where the core content of Strong Beginnings correctly draws on robust research showing clearly that human cognitive processes are largely the same, the corresponding section of the Standards emphasises teacher differentiation and suggests that the learning needs of various groups are different.

The Standards are a foundation of current ITE coursework, as well as in accreditation/registration processes for practicing teachers at all levels, and therefore represent a cornerstone of policy regarding teaching quality.

The Strong Beginnings report recommended mandating four areas of core content in initial teacher education (ITE) to align more closely with evidence of best practice. If these efforts are to be successful, standards also must be brought into line.

Consequently, this paper advocates a new set of Standards that are based on evidence. A model for policymakers is England’s Early Career Framework (ECF) which covers similar areas to the Standards but is far more detailed. For example, the ECF’s ‘Subject and Curriculum’ emphasises teacher knowledge, sequencing in the context of schema theory and retrieval and automaticity, whereas the Australian Standard 2 discusses student engagement and declines to specify what ‘well-sequenced’ means. Where the ECF specifies systematic synthetic phonics as a requirement for reading, the Australian Standards describe ‘literacy and numeracy’ in generalities.

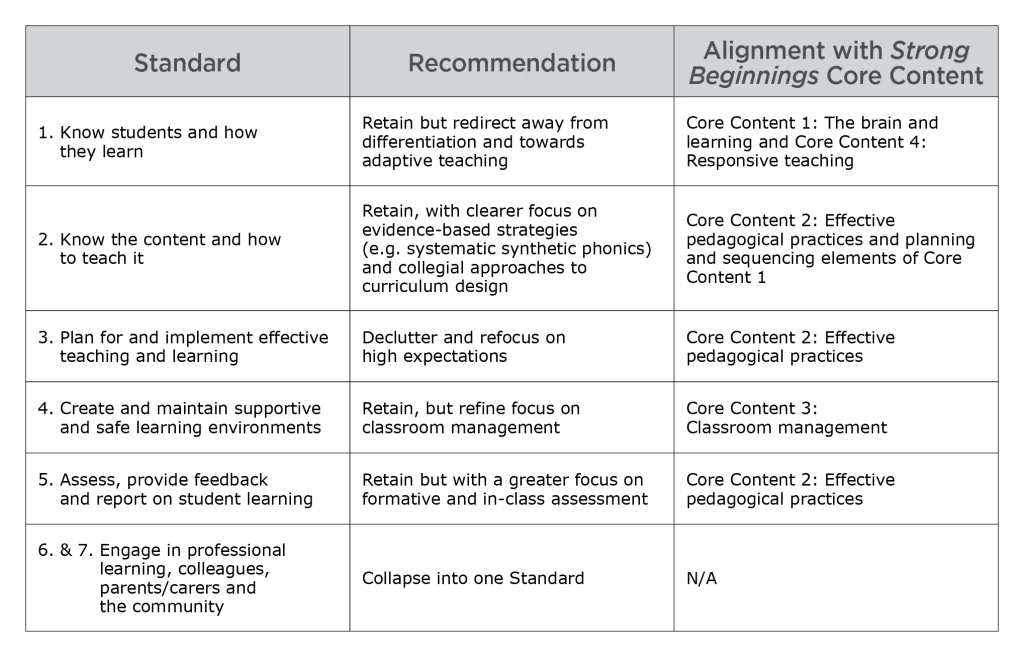

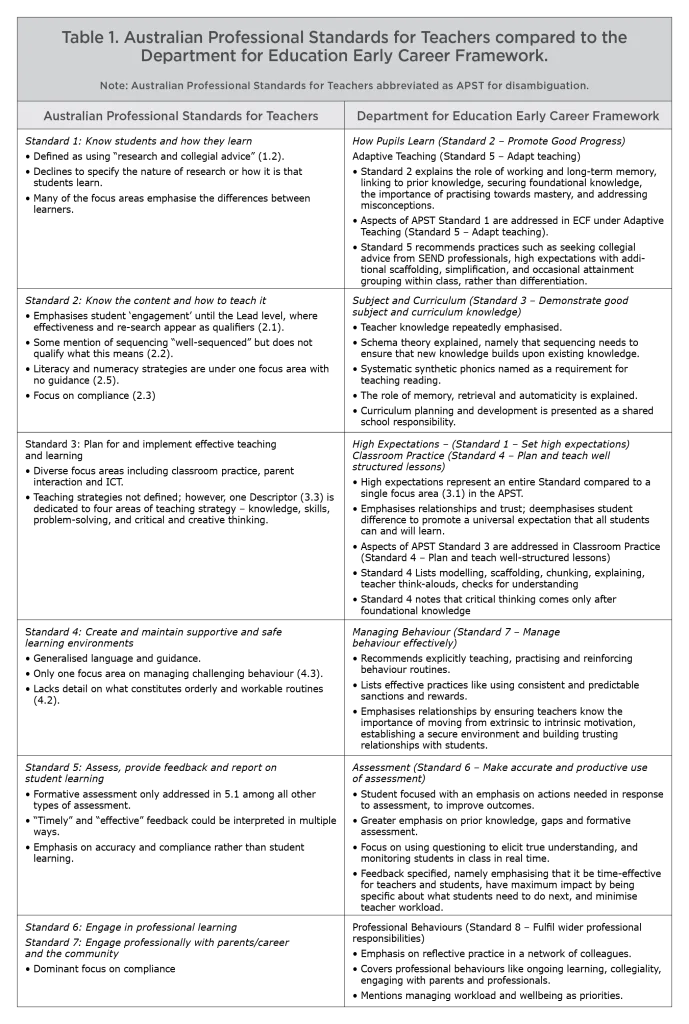

Some of the main reforms to the Standards and the alignment to the Core Content recommended in the paper are summarised in the following table:

The paper also makes the case that professional development aligned to new standards is key to driving teaching quality at all career stages. Models of professional learning that more clearly connect research to modelled practices and techniques, with time for practice, have better impacts on student outcomes. Individual schools such as Yates Avenue Public School in Sydney and school systems (such as the Catholic education dioceses of Canberra-Goulburn and Melbourne) are putting measures in place to retrain their teachers in ways that align with the core content and the revised standards advocated in this paper.

Overall, the paper recommends:

- Amending the Standards to reflect the core content, removing focus areas and integrating supporting documentation about exactly what teachers need to know and be able to do.

- Conducting factor and value-added analysis of any new Standards as part of their development, to ensure validity and rigour.

- Developing national guidelines for professional learning, including case studies of effective use of staffing and funding allocations.

With training in core content aligned to clear standards, combined with effective models of professional development to improve the capacity of all teachers at scale, the Standards can go from being a document only referenced by those seeking accreditation at certain career stages to a live and active vision of teacher professionalism.

2. Introduction

Australian student performance has been declining steadily for the last two decades. Recent PISA results show an overall downward trend in Mathematics, Reading and Science — and Australia significantly trails the OECD average.[1] Although there have been some recent improvements in global ranking, this can be explained partly by the learning loss of comparable nations in the wake of COVID-19. Similar concerns have been raised about student writing in Australia, with NAPLAN results revealing that many students structure sentences and use punctuation at a level that is two years behind their peers.[2]

In addition, Australian students report classroom climates that are unfavourable to learning, above the OECD average. Students often work in classrooms that do not listen to the teacher, where distraction is caused by others or as a result of lax school policy on digital devices.[3] The federal government has seen the need to invest considerable funding to redress a teacher knowledge deficit in effective classroom management.[4] Despite this, teacher unions continue to put up obstacles, arguing mostly for reductions in class size and the continued decoupling of teacher remuneration from student outcomes,[5] even though Australian teacher salaries have increased 15 per cent in real terms between 2010 and 2022.[6]

While much of the debate has concerned quantity of teachers in Australia, policymakers are also pursuing reform to achieve greater consistency in teacher preparation, accreditation and professional development. This can be observed, for example, through the National Teacher Workforce Action Plan (NTWAP).[7] As part of these reforms, in June 2023, the chair of the Teacher Education Expert Panel (TEEP) Professor Mark Scott handed down the Strong Beginnings report.

Strong Beginnings went much further than previous reform efforts in recommending the mandating of core content in initial teacher education (ITE) programs — and by extension, arguing for changes to the Accreditation of Initial Teacher Education Programs in Australia: Standards and Procedures (Accreditation Standards).

On July 6, 2023, all Australian education ministers agreed to enact the reforms, including bold targets to develop a national set of practical teaching guidelines; to amend the ITE Accreditation Standards by the end of 2023; and to ensure that the core content is included in all ITE programs by the end of 2025.[8]

The federal government has since committed $7.1 million in funding to support providers in implementing the core content, with an ITE Quality Assurance Oversight Board planned to ensure consistency and quality.[9] However, the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (Standards) are incompatible with the vision presented in Strong Beginnings. While they capture the breadth of teacher work,[10] they may not be fit for purpose, in part, because they do not reflect best practice in classroom teaching.

In turn, this has created problems of interpretation for ITE providers where course design and content mapping can easily become a compliance exercise. In their current form, the Standards lack the guidance necessary to support teachers in their professional growth. In essence, they are Standards without a standard.

With such a courageous shift from the anodyne reform efforts of the recent past, this moment represents an opportunity to ensure the Standards not only support the rigour so much needed in ITE, but actively support the professional knowledge, skill and growth of teachers at every career stage. The TEEP report recommended to amend the Accreditation Standards to accommodate the core content, however this may overburden providers already grappling with the breadth and open-endedness of the current Graduate Standards.

Since professional standards can and should help define what the profession values, these standards can be better leveraged to define, reflect and foster quality teaching practice. Therefore, a more effective and — in the long term more beneficial — approach may be to amend the Standards to reflect the core content.

Currently, the Standards are out of step with the evidence about what works in teaching and learning. Rather than exemplifying best practice, they are ambiguous and vague, inviting a breadth of unhelpful interpretations.

This paper seeks to make a pragmatic contribution to the ongoing discussion and policy process by first outlining the historical context and original intent of the Standards. It will then present an analysis of the evidence that ought to guide the establishment of teacher standards, followed by a critical discussion of the ways the current Standards fall short. The significance of teacher training in upholding these Standards will be discussed, along with the role of professional development in reinforcing standards. The paper will offer international standards as viable alternatives for consideration by policymakers. It will culminate in recommending specific amendments to the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers, underpinned by research.

The modifications aim to clarify and enhance the Standards, aligning them with best practice, thereby providing guardrails for impending reforms to ITE core content. Additionally, revised Standards will set clear expectations for the ongoing professional growth of the teaching workforce. The comprehensive application of the Standards across various policy areas highlights the critical need to offer concrete guidance to teachers in supporting student learning outcomes.

3. What are the Professional Standards for Teachers?

The national standards were developed by the Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL) and published in 2013. The Standards, administered by the states, are used for a number of critical purposes.

These include:

- to assess eligibility to teach

- to assess all levels of teacher accreditation, with associated increases in remuneration

- as a basis for quality control and content of ITE, and

- for meeting the professional learning requirements for maintenance of teacher accreditation/registration.

The case for a set of national teaching standards gained momentum in 1998, when the Australian Senate under then-Prime Minister John Howard published A Class Act: Inquiry into the Status of the Teaching Profession.[11] Influenced by transnational policy trends and the influential work of Linda Darling-Hammond and John Hattie, standards-based reform was seen as the key means to address underachievement.[12]

However, when the Melbourne declaration was signed in 2008, no agreement had been made by the states.[13] In response, the federal government offered funding incentives in exchange for their adoption.[14] Progress on implementation was slow, according to the 2014 TEMAG report, so the recommendation was made to align ITE to the Standards, hastening their integration.[15]

The Standards were written at a time when Australia was positioning itself as an increasingly global player, aiming to prepare students for the rapidly changing economy of the 21st century.[16] The genesis of the Standards as a vehicle for the goals of the Melbourne Declaration meant a focus on what – i.e., readiness for a global economy – rather than how.

The document reflected an increasing focus on individualism, emphasising “the ways different students learn”,[17] instead of their similarities. Technological readiness was also a focus, which has been intensified in the more recent Mparntwe Declaration,[18] published post-COVID-19 and online learning. Ten years later, the Standards remain unchanged, while the world of education has moved on.

At their point of inception, the Standards were intended to establish a set of “external norms”, elevating teaching beyond “a bunch of traits”.[19] Early proposals reinforced the importance of defining good teaching, going so far as to suggest domain-specific standards, and arguing against a generic approach. However, relativism was evident even in these early iterations, including qualifications that standards should “not standardise practice”.[20]

In a 2015 evaluation of the Standards, Stephen Dinham drew upon research into clinical teacher education programs and practice to identify key essential characteristics. Among these were:

- clarity of goals and the use of standards to guide performance and practice[21]

- similarly, clinical practice must acknowledge the highly complex and technical knowledge required of practitioners.[22]

While well-intentioned, the Standards in their current form have failed to live up to their promise to “outline what teachers should know and be able to do”.[23]

The Standards have largely escaped scrutiny in the discussion of what teacher professionalism may look like in the future. Despite the recent spate of policy activity, and their prevalence in policy and accreditation, the Standards as a lever for improving outcomes have been virtually ignored.

In 2020, AITSL commissioned a review of literature intended to inform future directions.[24] While Science of Learning is mentioned as a key development, the document doubles down on the emphasis on technology and the differences between learners, as well as suggesting an expansion of the Standards’ remit to student wellbeing and a greater emphasis on 21st century capabilities.[25]

More recently, the NTWAP[26] made little mention of the Standards, instead devolving discussion to the TEEP. In turn, the Strong Beginnings report attempted to map the proposed core content with the Standards, but this instead shone a light on their incompatibility.[27] Rather than perpetuating the emphasis in successive declarations, any future iterations of the Standards must be aligned to the core content, with the knowledge that well-prepared teachers have the greatest influence over any chance a student has at participating in the 21st century economic, social, or cultural arenas.

4. What evidence should inform teachers’ standards?

The process of developing standards invariably involves a range of stakeholders with varying areas of expertise and political agendas.[28] Stakeholder groups are diverse and not always compatible or unified, for example researchers, government, unions and parents.[29] This raises complex questions about who should have influence over the development of standards. However, in the case of the Standards, a lack of alignment with research evidence suggests that a recalibration may be needed.

Questions could also be asked about the relationship between certification and teacher effectiveness. Linda Darling-Hammond, whose work was influential on policymakers at the time that the notion of standards was gaining traction, correctly cites various teacher traits identified in certification standards as advantageous to student achievement.[30] However, the correlation of these qualifications with student achievement is erroneously assumed to show causation.[31] If standards are to truly influence teacher quality, upon what evidence should they be based?

Process product research provides valuable information about effective classroom practice. The work of Brophy and Good identified that pacing and volume of curriculum-related activities, with a high student success rate, is strongly linked to achievement.[32] Barak Rosenshine made similar observations about pace and volume,[33] adding that student outcomes were maximised when material was presented in small chunks — with teachers frequently checking for understanding, and material reviewed regularly.[34]

Some experimental and extensive correlational research has confirmed the usefulness of this field of research in determining the teacher behaviours that influence student outcomes. However, standards that focus purely on teacher actions in the classroom may be problematic; for example, some factors like direct instruction, student talk and drill have a curvilinear relationship with student learning.[35]

Several out-of-classroom factors should also be considered. For example, subject, pedagogy, and subject-pedagogy knowledge have been identified as important, but with mixed results on student performance, possibly due to their indirect nature.[36] There may also be interactive factors, such as the known relation between teacher-provided structure and autonomy support,[37] which make it difficult to isolate factors.

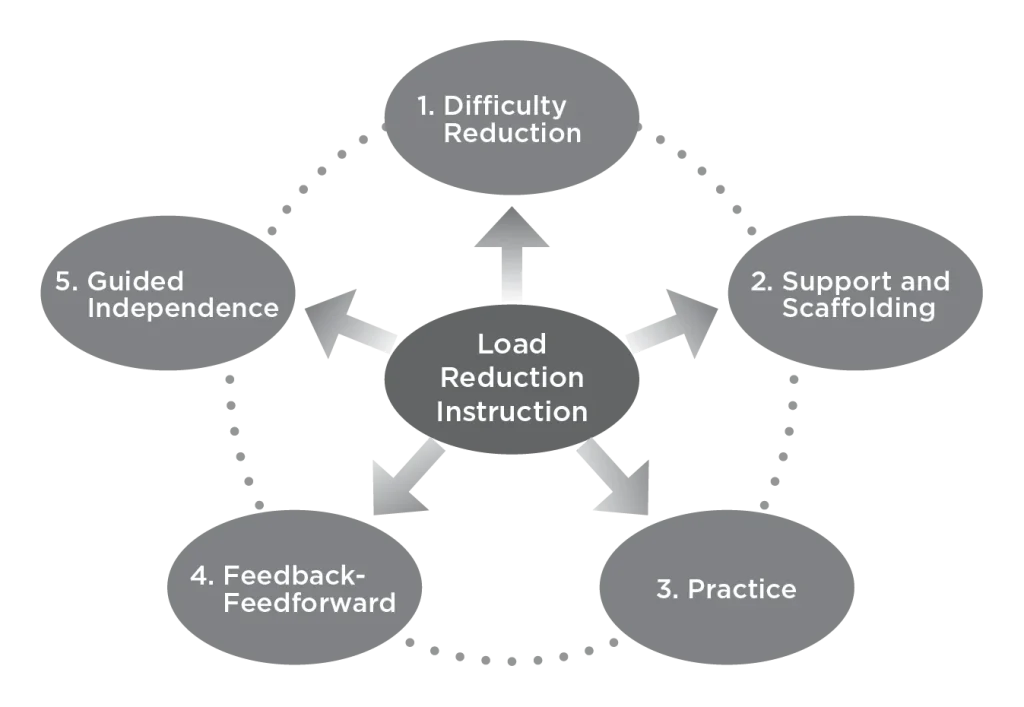

One model that goes beyond individual teacher behaviours to present a cycle of practices is load reduction instruction. Devised by Andrew Martin,[38] the model operationalises cognitive load theory, simplifying the principles for classroom teachers.[39] The framework also takes into account Kalyuga’s expertise reversal effect,[40] whereby students’ learning can be held back by prolonged explicit instruction and load reduction.

The cycle of learning (see Figure 1) takes students through the novice to expert continuum, accounting for the interactive effects of teacher-provided structure and autonomy support through guided practice and eventual mastery. This model has been linked to student outcomes[41] and engagement,[42] but has also been validated using student[43] and teacher self-report.[44] Not only is the model rigorous and with a strong evidence base, with its sequential trajectory from knowledge acquisition to critical thinking, it satisfies the 21st century skills agenda in a way that the current Standards do not.

Figure 1. The load reduction instruction framework. Source: Andrew J. Martin and Paul Evans, ‘Load Reduction Instruction (LRI)’, in Advances in Cognitive Load Theory. Routledge, 2019.

While the breadth and specificity of teacher actions is difficult to define, standards should at least have predictive power and validity. In other words, they should measure what they claim to measure, and higher scores should show a positive relationship with student outcomes. North Carolina researchers have conducted investigations into whether the rubric used to assess preservice teachers has predictive validity.[45] Indeed, the instrument measured the intended behaviours with strong factor loadings, suggesting that the scoring rubrics indicate teacher actions as intended.[46]

In addition, seven of the 15 individual rubrics predicted teacher value-added estimates.[47] Subject-specific pedagogy and planning for content understanding held the greatest predictive power on value-added estimates, [48] showing the connection between in-class and outside-class factors. The ‘black box’ factor remains in that standards don’t necessarily illuminate what teachers should do, the dosage, or combinatory effects. However, in the North Carolina instance, the demonstrated validity and positive relationship with student outcomes holds greater indicative power for guiding teacher quality than unvalidated measures. It is unclear whether tests of validity have been conducted on the Australian Standards, nor their relationship to value added measures.

4.1 How the Standards fall short of the evidence

The core content established in Strong Beginnings marks a notable shift away from the progressive sociological model of ITE favoured by many universities. Rather than an emphasis on teacher preference and professional identity, the core content identifies practices that are known to work for most students.[49] For example, core content on ‘The brain and learning’ draws upon 30 years of robust and replicated cognitive science, covering cognitive load theory,[50] the novice to expert continuum, and the importance of retrieval (or self-testing).[51] It even counters long held and perpetuated misconceptions about learning. ‘Effective pedagogical practice’ recentres the teacher through explicit instruction and prescribes phonics as essential to the teaching of reading.

Similarly, behaviour routines are presented as being teachable, and explicit instruction is mentioned as conducive to a calm classroom environment. Notably, the content shifts away from differentiation, the practice of creating alternative tasks for students according to their ability. Instead, it recommends quality whole-class instruction with multi-tiered systems of support[52] and responsive teaching, which has potentially positive implications for teacher workload.

While the core content specifies effective practices, going as far as to say that whole-class, explicit teaching is highly effective for diverse learners, Standard 1, Know students and how they learn, emphasises teacher differentiation. Focus areas 1.1, 1.3 and 1.4 suggest that the learning needs of various groups — including economics groups — are different.

Standards 1.5 and 1.6 both address differentiation and disability, implying that teachers personalise learning for an impossible range of learners. The redundancy in this area reflects the emphasis in both the Mparntwe[53] and Melbourne[54] Declarations and has been noted in OECD comparative analysis of international teaching standards.[55]

Standard 1.2 is agnostic about exactly “how students learn,” rather than focusing the practices that research has demonstrated to be effective across contexts and for the most learners.[56] “Using research” is mentioned, but problems of rigour are well known in the field of education, and despite decades of evidence drawn upon in the core content, “what works” is still hotly contested; therefore, the Standards currently provide little support for ITE providers and teachers.

The current Standards emphasise curriculum writing -— the translation of mandated curriculum into scopes and sequences, unit plans and lesson resources — as a key teacher skill, and this is reflected in many ITE programs. The core content makes no mention of curriculum and lesson design, reflecting more recent thinking of curriculum as a collaborative process and a shared responsibility.

Research by the Grattan Institute suggests that individual curriculum planning is often ineffective and unnecessarily burdensome, especially for teachers in the early stages of their career.[57] Other than Standard 2.1 which emphasises student “engagement” at the Proficient level, the Standards provide no qualitative guidance about what constitutes good curriculum, with tacit knowledge expected about what “effective” or “sequenced” curriculum looks like. The framing of these descriptors is highly teacher-focused, with little emphasis on the way that students learn, i.e., through knowledge and skills broken into small chunks and built upon cumulatively.

Without a clear hierarchy of importance within the different Standards, or qualitative guidance, universities have been free to place their course emphasis where they choose, resulting in variable ITE provision. For example, Standard 1.2, “how students learn”, is prerequisite to knowing “the content and how to teach it”. In a post COVID-19 world where teachers quickly adapted to online learning, the repeated references to Information and Communication Technology (ICT) feel outdated (2.6, 3.4, 4.5), a legacy of the time that the Standards were created.

In contrast, classroom behaviour rates a single mention, where Proficient teachers are given vague directives to “negotiate” expectations with challenging students. A lack of hierarchy also has implications for the successful completion of professional placements, where understanding of professional behaviours (Standards 6 and 7) is of far less urgency than classroom management. Poor classroom management is linked to high rates of teacher attrition,[58] and the robustness of ITE in this area was the subject of a recent Senate inquiry, indicating the urgent need to reform the Standards.[59]

4.2 How the Standards could support teacher workforce needs

The existing limitations of the Standards are amplified when applied to the current Highly Accomplished or Lead Teacher accreditation process (HALT is a designation used in most Australian States). If there is agnosticism about “how students learn” in the Proficient teacher standards, this is magnified in the Highly Accomplished evidence guide,[60] with an emphasis on “innovative practice” (2.2.3), where applicants are expected to generate “alternate, evidence-based strategic solutions and new, innovative teaching practices”.

In addition, many of the descriptors are unlikely to be met by outstanding teachers whose aim is to support other teachers with their practice while continuing to teach. Rather than looking at the role of a HALT as a discrete career path, the Standards instead add adjectival intensifiers to descriptors or a requirement to “support colleagues” in many areas, regardless of the applicant’s role, strengths, or domain specialism.

One goal of the Teacher Workforce Action Plan is to increase the numbers of HALTs influencing practice,[61] with the potential for these leaders to support preservice and early career teachers (ECTs). However, the project is held back by a lack of consideration of the work of specialists like instructional, curriculum or literacy leaders.

As of 2022, only around 1000 teachers nationally had achieved HALT accreditation, despite process simplification and bold targets.[62] The original proposal for teacher standards floated the idea of domain-specific and promotion standards[63] and this would be a positive move towards recognising specialist positions like the Master Teacher roles proposed in the recent National School Reform Agreement.[64] It is recommended that rather than doubling down on the HALT program and ‘upsizing’ the existing Standards, teachers should be able to nominate discrete Standards of specialism so that their expertise can be recognised and shared.

Australia faces unique challenges, with teacher shortages keenly felt in rural and remote schools.[65] Technology has increasingly been used to support teaching candidates during placements,[66] and could be employed with the support of the proposed Master Teachers to ensure the benefits of peer observation and instructional coaching are available to all.

As previously mentioned, the emphasis on curriculum design in the current Standards reflects what seems to be another uniquely Australian attitude towards teacher professionalism,[67] which favours the idea of writing whole units and lessons from scratch. Fortunately, this is changing with the rising popularity of organisations like Ochre Education who have partnered with Catholic Education Canberra Goulburn to ensure high quality curriculum not only within their system but to be shared with other schools.[68] These free products are particularly valuable to remote, very remote and small schools. A reduced focus on this drain on teacher time[69] would potentially improve retention and enable a focus on instruction.

5. What role does teacher preparation play in reinforcing the Standards?

In Australia, for ITE programs to be accredited they must demonstrate that their graduates meet the Graduate Teacher Standards.[70] However, a huge number of providers (compared to high-performing Singapore with just one, and fast-improving Estonia with two) means that course content can be harder to monitor for quality or compliance.[71] Learning outcomes are often loosely aligned with the Standards and universities can include additional content, such as contemporary educational issues and theory.[72]

In addition, the Standards require extensive implicit knowledge about teaching and learning,[73] which often originates from outside the education faculties, deriving instead from fields like educational psychology and reading science. In many cases, the Standards have simply functioned as a content map for providers,[74] with the void of detail inviting a palimpsest of sociological critiques and ideologies in ITE programs, in place of essential teacher knowledge and skill.

Since their inception the Standards have promised to outline “what teachers are expected to know and be able to do”,[75] but have neglected to define what this is. Priority Reform 1 of the TEEP report aims to address this and promises to “support ITE students in meeting the Graduate Teacher Standards”.[76] In contrast, the mandated core content specifies exactly what teachers need to know, to “have the greatest impact on student learning”,[77] suggesting a move away from the pedagogical agnosticism of the recent past.

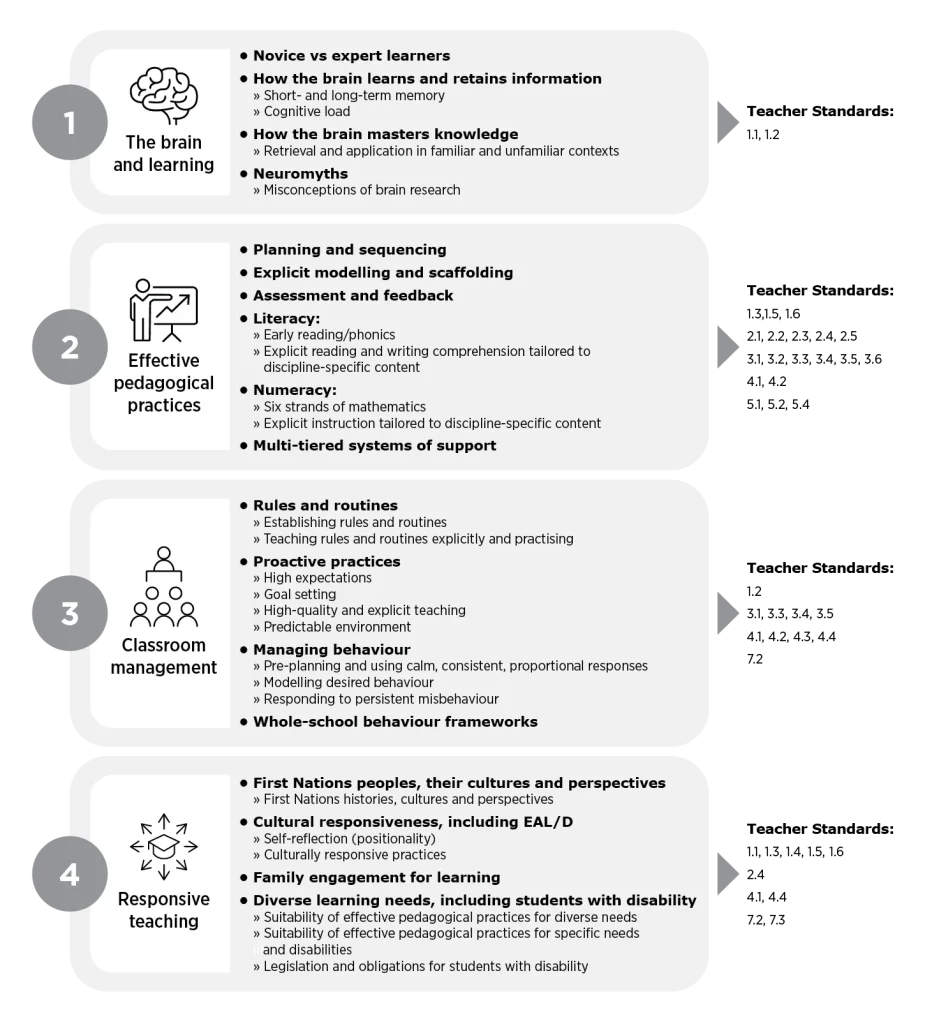

Four key content areas for ITE delivery are identified, namely ‘The brain and learning’, ‘Effective pedagogical practices’, ‘Classroom management, and ‘Responsive teaching’ – see Figure 2. It will be important that any future Standards meaningfully support not only graduates but the professional development of teachers at all career stages.

Figure 2. The core content showing planned alignment to the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers. Source: Mark Scott, Strong Beginnings.

Soon after the report’s release, providers came out strongly against the reforms, claiming at once that the core content is already being taught,[78] while resisting some of the basic principles put forward.[79] The prevailing view is that teachers are already professional experts, and any attempt to define good teaching is bureaucratic overreach at best and teacher-bashing at worst.[80]

The requirement for ITE to align with standards was in itself a relatively recent phenomenon. Even still, the current Graduate Standards, with their lack of specificity, have enabled ITE providers up until this point to ‘choose their own adventure.’ The risk is that without a set of standards that are as qualitatively helpful and robust as the core content in Strong Beginnings, which prioritised cognitive science and explicit teaching, the education sector may be headed towards yet another period of stagnation.

If the planned reforms are to make an impact, continuity will be needed not only in the Standards themselves, but in their implementation and in-school support. One of the main criticisms of the TEEP report fell outside the Panel’s terms of reference, namely that preservice and graduate teachers were not given enough support during their early careers.

However, work needs to be done in supporting ITE students to reach the starting line in their careers. Priority Reform 3 highlighted the lack of consistency in professional placements, describing these euphemistically as a “spectrum” of experiences.[81] Without an amended version of the Standards, preservice teachers may find themselves without a shared understanding of quality teaching with the mentors assigned to support them. As AITSL notes, “If ITE is the only focus for the opportunity to improve [the capacity of the teaching workforce], it will take approximately 28 years for the workforce to achieve what is desired”.

6. What role does professional development play in supporting quality teaching?

An oft-cited review of what works by the Learning Policy Institute cites professional learning that is content focused, incorporates active learning, supports collaboration, and uses modelling of practice as elements of effectiveness.[82] However, many of the cases used in evidence, such as the now debunked Reading Recovery program, require vast amounts of resources to implement effectively, making the advice impractical and the evidence questionable.[83]

Indeed, much of the research used to support these putative features of effectiveness are based on substandard research designs.[84] In addition, researchers have struggled to extract the causally active from inactive components of teacher professional learning.[85] To this end, Sims et al., conducted more rigorous meta-analysis on the features of effective professional learning and found programs that featured a balance of (a) teacher theoretical learning (named in the study as ‘insights’; (b) goals related to changing practice; (c) practical models of techniques; and (d) time for practice; had a greater impact on outcomes than programs which featured fewer or simply individual elements.[86]

Teacher habits can be deeply embedded and resistant to change, therefore instructional coaching which features the elements identified by Sims et al.,[87] holds great promise. In these models, teachers embed more effective behaviours through observing their own practice, observing an instructional coach modelling these behaviours, and then repeatedly practising these new techniques in the classroom (for an example of one such model, see Box 1).

Just like the proposed amendments to the Standards, coaching should provide teachers with specific goals and the support to achieve them.[88] Models of professional development which focus on observation could provide support not only for ECTs but could ensure that the core content filters up to teachers at all career stages.

Quality Teaching Rounds has been put forward as a model in successive reports;[89] however, the program has a questionable evidence base despite the millions invested and is based on highly subjective dimensions like ‘narrative’, ‘higher-order thinking’ and ‘problematic knowledge’.[90] The process of professional reading, coding according to vague criteria, then discussing the observations is also time-intensive at a time of teacher shortages and workload pressures.

| Box 1 – An Instructional Coaching Model

Ambition Institute in the UK provides a practical, achievable, and evidence-aligned model via its Incremental Coaching in Schools program.[91] Teachers commit to short, low-stakes observations by an instructional coach, receive rapid feedback without judgement, and skills are then role-played or simulated by the coach for the teacher to try in an upcoming lesson. Rubrics can be created to align to core content but also to school priorities, e.g., the inclusion of instructional non-negotiables like daily review. Importantly, hierarchies of priorities are acknowledged; for instance, basic classroom management and routines are seen as more imperative than downstream practices like differentiation.[92] While the process is comparatively time-efficient, some operational support is needed for coaching programs to succeed, such as release time for coaches and coaching conversations. Similarly, non-judgemental coaching conversations are a discrete skill and require investment in training to ensure consistency in the quality and capacity of coaches.[93] |

An alternative model is Steplab[94] from the UK, which utilises an online platform and video demonstrations as a model of best classroom practice. A notable feature is that situational instructional leadership is used to ‘diagnose’ the level of direction a teacher needs with their practice.[95] While teacher autonomy is an influence on teacher retention, it has little effect on student outcomes. It is appropriate to give novice teachers higher levels of direction and support. The Steplab process chunks teacher skills into manageable ‘steps’ with the view to later adopting these as part of a more cohesive whole.

The model acknowledges the potential cognitive load inherent in teaching for new teachers. In addition, some skills need more urgent development than others. As mentioned, classroom management is linked to early career teacher attrition.[96] Similarly, managing attention is a frequently noted issue in pre-service teacher observation scores.[97] While the Steplab model does not take into account interactive effects like those of load reduction instruction, the professional learning is meaningful, practical and manageable.

Many Australian schools (see Box 2) and even school systems (such as the Catholic education dioceses of Canberra-Goulburn and Melbourne) have already put measures in place to retrain their teachers in core content principles and instructional coaching practices. While amended Standards will inevitably support these new criteria, schools and systems need not wait to help all teachers to see the benefit of these reforms.

| Box 2. How one school defined and met their own set of standards

When David MacSporran took over the principalship at Yates Avenue Public in Dundas Valley NSW, the school was underperforming when compared to similar schools and the state. While it is nestled within a relatively affluent area, the school serves a small pocket of disadvantage, with 29% of families occupying the bottom quartile of the Index of Community Socio-Educational Advantage (ICSEA) and 55% of students with a language background other than English. David’s professional learning strategy has seen the school’s NAPLAN results climb, particularly in Mathematics. As of 2023, 84% of Yates Avenue students (Year 3 and 5 combined) achieved in the top two proficiency bands in Mathematics, compared to 69% of NSW students. In 2019, Yates Avenue was below the state average in all strands, and by 2023, students were placed in the top 10% in NSW. David’s first step was to introduce the TAPPLE sequence and engagement norms developed by Hollingsworth and Ybarra.[98] TAPPLE involves explicitly teaching new content before checking that the majority of students have understood, before providing corrective feedback or reteaching. He believes it’s important to “get the basic practices right” before rolling out something like an instructional playbook which defines and encodes the intentional practices used by a school. Next, the school implemented daily reviews to reinforce essential learning, as per the recommendations of Rosenshine.[99] Also essential to their success was the appointment of a specialist instructional coach in the role of Assistant Principal Curriculum and Instruction (APCI), to “work shoulder to shoulder with teachers”. He recommends developing someone internally who has credibility in the school, saying that peer observations and support from an instructional leader are the “holy grail” of professional learning. The teachers of Yates Avenue also joined forces with a network of other schools in the greater Sydney, the Central Coast and Newcastle regions to develop units of work featuring explicit instruction, aligned with the new mathematics curriculum. David extends the sharing of the expertise within his school by hosting regular open days for other teachers to observe, also loaning his key APCI to other schools so that they too can develop their practice. He remarks that it is an “expensive exercise in resource sharing,” but that “the work has to be done – it’s too important not to”. However, he also observes that cost reduction was achieved elsewhere, noting the reduced need for staffing of intervention classes run on a withdrawal model. He also replaced his English as a Second Language and Learning & Support teachers with an additional, school-funded class to reduce overall class sizes, focus on Tier 1 practice and support the implementation of the schools’ instructional model. Staffing stability is a key factor of the school’s success. When recruiting, David is always up-front about the school’s teaching and learning focus at Yates Avenue, remarking that it puts some off joining the school, but equally attracts already-likeminded teachers. He says that with new staff untrained in the methods at Yates, it’s up to the leadership team to ensure teachers have what they need to teach explicitly. When asked if people are happy at Yates Avenue, David says, “the kids are successful at Yates. We have a ton of data on that”. But regarding teachers, David thinks that turnover is a reliable metric. There are always going to be schools that are in some ways “easier,” but teachers are generally not leaving. |

7. What do best examples of standards in practice suggest for policymakers?

The Strong Beginnings report proposed a way to map the existing Standards to the core content. However, this overlaying may prove cumbersome for ITE providers to meaningfully align their programs, and the risk of selective interpretation and emphasis would remain. Practising teachers also would receive no updated knowledge, skills or expectations, should the Standards remain as they are for the purposes of annual accreditation/registration. Instead, any alignment at the Proficient level and above would rely on schools serendipitously happening upon this policy reform, then implementing professional learning on core content.

Without concomitant amendments to the Standards, teacher-mentors and schools may be limited in their ability to support pre-service teachers, due to the variable quality and content of ITE they themselves may have received. On a broader level, it would be a missed opportunity if the core content was made available only to new graduates, rather than being adopted in the Standards for the benefit of all teachers and, by extension, their students.

Looking internationally, many examples of teacher certification standards, even in high performing or notably improving jurisdictions, appear to promote a similar breadth of content to the Australian Standards, with a similar lack of accompanying guidance or evidence-base.

While attempts have been made to validate the North Carolina Professional Teaching Standards,[100] they share a focus on 21st century skills, critical and creative thinking, and diversity of learners, positioning teachers as ‘facilitators’ of learning.[101] The state of Mississippi defers to the National Board of Professional Teaching Standards, which provides extensive elaboration, but little of a practical nature.[102] The Mississippi standards also include outdated beliefs about the different “learning styles” of students.[103] In contrast to a purely descriptor-based set of standards, as with the Australian model, Singapore has subsumed the Graduand Teacher Competencies used by their single ITE provider to formulate a TE21 framework , featuring skills and knowledge as central, but also advising teachers to choose pedagogies according to their own personal values.[104]

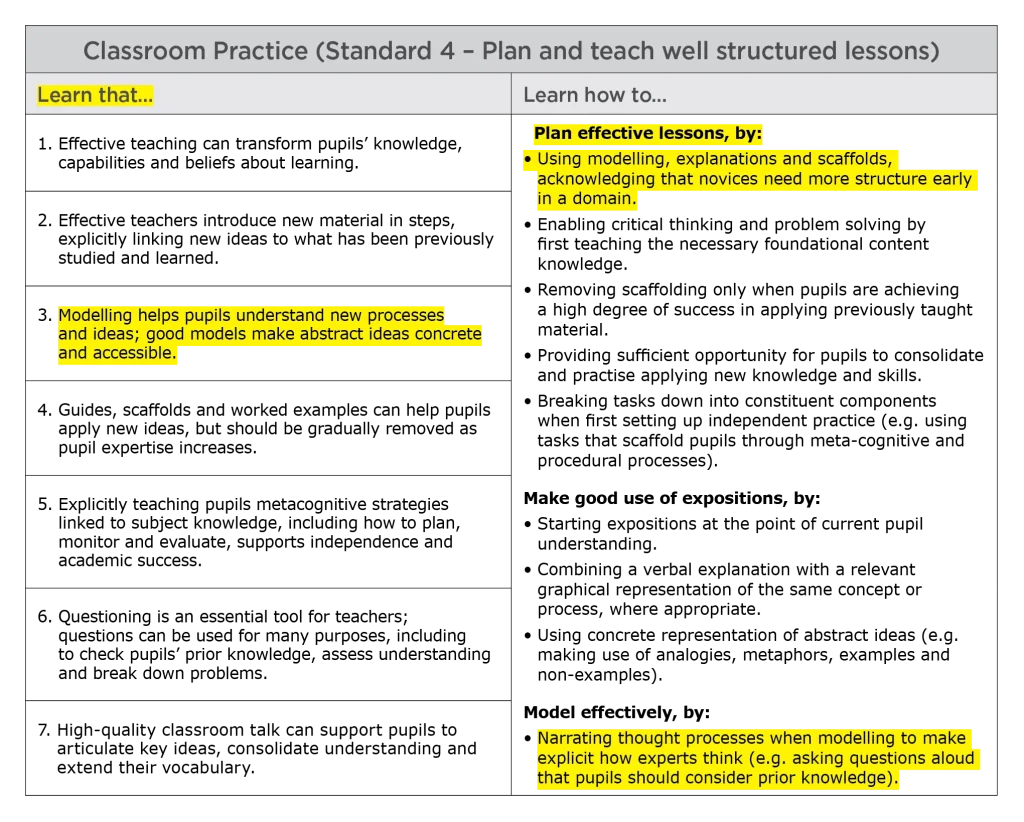

By far the most promising alternative is the UK Department for Education (DfE) Early Career Framework (ECF). Endorsed by the Education Endowment Foundation and based upon the strongest research-evidence, the ECF provides a model of how to make ‘what teachers are expected to know and be able to do’ explicit. The framework not only aligns to the UK Teachers’ Standards,[105] but acts as a support document for teachers at any career stage.

The document is unequivocal and concise. For example, instead of differentiation, ECTs are given highly practical advice like the utility of “Balancing input of new content so that pupils master important concepts”.[106] In Australia, the HALT process is supported by more than 100 pages of guidance; this would be a hindrance to any amendment of the Standards. Rather than a separate support document, the ECF integrates succinct specifications of what teachers need to know and do.

Figure 3. A sample of the guidance offered in the DfE Early Career Framework. The highlighted areas indicate the parts that align and are relevant to each other.

The following is an appraisal of the Standards against the Early Career Framework, followed by broad recommendations about amendments to the Australian Standards. In the left column are the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers and in the right are the ECF equivalents. This analysis is not designed as an exhaustive critique. It is rather an illustration of the differences in emphasis and specificity of the two documents, with the intention that a framework featuring this level of support be considered in any future reviews of the Standards.

8. What should we do in Australia to better match our standards to evidence and best practice?

The following section proposes amendments to the Standards, so that the impact of core content can potentially benefit not only future pre-service and graduate teachers but all teachers. Broadly, the documents differ in four main ways:

- their alignment to evidence-based practice

- the pragmatic approach to supporting teachers by naming effective strategies, including for diverse student groups

- the focus on supporting teacher growth, rather than curriculum and compliance

- and emphasis (or lack) on ICT.

With these points in mind, this research paper makes the following broad recommendations:

- Retain Standards 1 – 5 (Know students and how they learn; Know the content and how to teach it; Plan for and implement effective teaching and learning; Create and maintain supportive and safe learning environments; Assess, provide feedback and report on student learning), but remove or consolidate existing focus areas. Develop amended capacity-based Standards 1 – 4 from the learning outcomes[107] in the core content, capturing essential teacher knowledge like cognitive load theory and the novice to expert continuum, including the scaffolding of new learning; the fact that learners are more similar than different; and that student relationships develop in environments of routine, high expectations and safety.

- Standard 1, Know students and how they learn, should include Core Content 1 — ‘The Brain and Learning’; and Core Content 4 — ‘Responsive Teaching’, to cover the breadth of the extant focus areas which centre on how students learn, but also practices previously conceptualised as differentiation. Redundancy in this area should be removed.

- Standard 2, Know the content and how to teach it, should draw from Core Content 2 — ‘Effective Pedagogical Practices’, and the planning and sequencing outcomes of Core Content 1. Any new Standards must explicitly mention systematic synthetic phonics, and fluency in mathematics. Emphasis on curriculum design and compliance should be reduced and instead, collegial approaches to implementing and adapting curriculum should be emphasised.

- Standard 3, Plan for and implement effective teaching and learning, should be decluttered, and focus on high expectations, as per the ECF, and the learning outcomes of Core Content 2 — ‘Effective Pedagogical Practices’.

- Standard 4, Create and maintain supportive and safe learning environments, should focus on Core Content 3 — Classroom Management, only.

- Standard 5, Assess, provide feedback and report on student learning, should feature greater emphasis on in-class and formative assessment as per Core Content 2. The ECF should also inform any amendments, to ensure that teachers understand that individual feedback is not always the most effective or efficient use of teacher time. This is essential in the context of teacher workload issues and associated teacher shortages.

- Standards 6, Engage in professional learning, and 7, Engage professionally with colleagues, parents/carers and the community, should be collapsed into one Standard 6: Professional Engagement.

9. Conclusions

The reforms put forward in Strong Beginnings will have little impact without a review of the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers. The current Standards list the breadth of teachers’ roles but provide little qualitative support for teachers at any career stage. In their current form, they are evidence-neutral. While the core content is set to be mandated as part of ITE, the risk is that the Standards left in their current form will encourage a tokenistic approach to these mandates from universities, which have expressed some resistance to the Strong Beginnings reforms.

Given the extensive relevance of the Standards to several aspects of the policy landscape, it is imperative that they provide genuine support to teachers at all career levels in their crucial work in driving student learning outcomes. Therefore, Strong Beginnings’ core content must be translated into a new iteration of the Standards. For the Standards to support teacher development, they need to draw on established cognitive science, and more closely resemble a document like England’s Early Career Framework.

Reforming the Standards in the manner advocated in this paper would provide more explicit guidance for impending reforms to ITE core content, as well as set clear expectations for the remainder of the teacher workforce.

The reforms that will benefit graduates need vertical integration with the profession as a whole for early career teachers to be effectively supported and for teaching practice to align with the research that has been shown to produce the strongest student outcomes. With training in core content aligned to clear standards and combined with effective models of professional development to improve the capacity of all teachers at scale, the Standards can go from being a document only referenced by those seeking accreditation at certain career stages to a live and active vision of teacher professionalism.

This can be achieved by the following:

- Amend the Standards to reflect the core content, removing focus areas and integrating supporting documentation about exactly what teachers need to know and be able to do.

- Conduct factor and value-added analysis of any new Standards as part of their development, to ensure validity and rigour.

- Develop national guidelines for professional learning, including case studies of effective use of staffing and funding allocations.

Endnotes

- OECD, ‘Australia | Factsheets | OECD PISA 2022 Results’, OECD, 2023, https://www.oecd.org/publication/pisa-2022-results/country-notes/australia-e9346d47#section-d1e214.

- Australian Education Research Organisation, ‘Writing Development: What Does a Decade of NAPLAN Data Reveal?’, 2022, https://www.edresearch.edu.au/sites/default/files/2022-10/writing-development-summary-aa.pdf.

- OECD, ‘Australia | Factsheets | OECD PISA 2022 Results’.

- Ministers’ Media Centre, ‘More Support for Teachers to Manage the Classroom’, 2 May 2023, https://ministers.education.gov.au/clare/more-support-teachers-manage-classroom.

- Jordan Baker, ‘Performance Pay, Revamped School Hours: Premier Flags Education Reforms’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 18 June 2022, https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/performance-pay-revamped-school-hours-premier-flags-education-reforms-20220617-p5aula.html.

- [6]Natasha Bita, ‘Soaring salaries place Australian teachers top of the class’, The Australian, 12 September 2023, https://www.theaustralian.com.au/nation/soaring-salaries-place-australian-teachers-top-of-the-class/news-story/daba7a6a5875b9c1ad686acdccf6c507

- Australian Government Department of Education, ‘National Teacher Workforce Action Plan’, 15 December 2022, https://www.education.gov.au/national-teacher-workforce-action-plan.

- Australian Government Department of Education, ‘Education Ministers Meeting Communiqué – July 2023’, 6 July 2023, https://www.education.gov.au/education-ministers-meeting/resources/education-ministers-meeting-communique-july-2023.

- Australian Government Department of Education, ‘Education Ministers Meeting Communiqué – December 2023’, Text, 12 December 2023, https://www.education.gov.au/education-ministers-meeting/resources/education-ministers-meeting-communique-december-2023.

- Lawrence Ingvarson, ‘Development of a National Standards Framework for the Teaching Profession’, Policy brief, May 2002.

- Glenn C. Savage and Steven Lewis, ‘The Phantom National? Assembling National Teaching Standards in Australia’s Federal System’, Journal of Education Policy 33, no. 1 (2 January 2018): 118–42, https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2017.1325518.

- Savage and Lewis.

- Savage and Lewis.

- Savage and Lewis.

- Savage and Lewis.

- Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs, ‘Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians’, 2008.

- Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs, 11.

- Department of Education, Skills and Employment, ‘The Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration’, 2019, https://www.education.gov.au/alice-springs-mparntwe-education-declaration/resources/alice-springs-mparntwe-education-declaration.

- Richard Elmore, ‘Getting to Scale with Good Educational Practice’, Harvard Educational Review 66, no. 1 (1996): 1–27.

- Ingvarson, ‘Development of a National Standards Framework for the Teaching Profession’.

- Stephen Dinham, ‘Issues and Perspectives Relevant to the Development of an Approach to the Accreditation of Initial Teacher Education in Australia Based on Evidence of Impact’, 1 May 2015, 4, http://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/initial-teacher-education-resources/ite-reform-stimulus-paper-03-dinham.pdf.

- Dinham, 4.

- Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership, ‘Australian Professional Standards for Teachers’, 2018, https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/national-policy-framework/australian-professional-standards-for-teachers.pdf?sfvrsn=5800f33c_64.

- Kerry Elliott et al., ‘Environmental Scan Topical Areas to Inform a Future Review of the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers’, Final Report, 2020.

- Elliott et al.

- Australian Government Department of Education, ‘National Teacher Workforce Action Plan’.

- Scott, ‘Strong Beginnings’.

- Nóra Révai, ‘A Review with Case Studies on Australia, Estonia and Singapore’ (OECD, 2018), https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/what-difference-do-standards-make-to-educating-teachers_f1cb24d5-en.

- Révai.

- Linda Darling-Hammond and Peter Youngs, ‘Defining “Highly Qualified Teachers”: What Does “Scientifically-Based Research” Actually Tell Us?’, 2002, https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X031009013.

- Darling-Hammond and Youngs.

- Jere Brophy, ‘Teacher Influences on Student Achievement’, American Psychological Association 41, no. 10 (1986): 1069–77.

- Barak Victor Rosenshine, ‘Academic Engaged Time, Content Covered, and Direct Instruction’, Journal of Education 160, no. 3 (August 1978): 38–66, https://doi.org/10.1177/002205747816000304.

- Barak Rosenshine, ‘Principles of Instruction – UNESCO Digital Library’, 2010, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000190652.

- P. M. Creemers and L. Kyriakides, ‘Critical Analysis of the Current Approaches to Modelling Educational Effectiveness: The Importance of Establishing a Dynamic Model’, School Effectiveness and School Improvement 17, no. 3 (1 September 2006): 347–66, https://doi.org/10.1080/09243450600697242.

- Bert Creemers and Leonidas Kyriakides, ‘Process-Product Research: A Cornerstone in Educational Effectiveness Research’, Journal of Classroom Interaction 50, no. 2 (2015): 107–19.

- Hyungshim Jang, Johnmarshall Reeve, and Edward L. Deci, ‘Engaging Students in Learning Activities: It Is Not Autonomy Support or Structure but Autonomy Support and Structure.’, Journal of Educational Psychology 102, no. 3 (August 2010): 588–600, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019682.

- Andrew J Martin, Using Load Reduction Instruction (LRI) to Boost Motivation and Engagement (Leicester, UK: The British Psychological Society, 2016), 2016.

- Slava Kalyuga, ‘Expertise Reversal Effect and Its Implications for Learner-Tailored Instruction’, Educational Psychology Review 19, no. 4 (1 December 2007): 509–39, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-007-9054-3.

- Andrew J. Martin et al., ‘Load Reduction Instruction in Science and Students’ Science Engagement and Science Achievement.’, Journal of Educational Psychology 113, no. 6 (August 2021): 1126–42, https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000552.

- Martin et al.

- Andrew J. Martin and Paul Evans, ‘Load Reduction Instruction: Exploring a Framework That Assesses Explicit Instruction through to Independent Learning’, Teaching and Teacher Education 73 (1 July 2018): 203–14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.03.018.

- Andrew J. Martin et al., ‘Load Reduction Instruction in Mathematics and English Classrooms: A Multilevel Study of Student and Teacher Reports’, Contemporary Educational Psychology 72 (1 January 2023): 102147, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2023.102147.

- Kevin C. Bastian, Diana B. Lys, and Waverly R. L. Whisenant, ‘Does Placement Predict Performance? Associations Between Student Teaching Environments and Candidates’ Performance Assessment Scores’, Journal of Teacher Education 74, no. 1 (1 January 2023): 40–54, https://doi.org/10.1177/00224871221105814.

- Bastian, Lys, and Whisenant.

- Bastian, Lys, and Whisenant.

- Bastian, Lys, and Whisenant.

- Australian Education Research Organisation, ‘“But That Would Never Work Here” – Does Context Matter More than Evidence?’, 27 September 2022, https://www.edresearch.edu.au/other/articles/would-never-work-here-does-context-matter.

- Paul A. Kirschner, John Sweller, and Richard E. Clark, ‘Why Minimal Guidance During Instruction Does Not Work: An Analysis of the Failure of Constructivist, Discovery, Problem-Based, Experiential, and Inquiry-Based Teaching’, Educational Psychologist 41, no. 2 (1 June 2006): 75–86, https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_1; Kalyuga, ‘Expertise Reversal Effect and Its Implications for Learner-Tailored Instruction’.

- Elizabeth Ligon Bjork and Robert A. Bjork, ‘Making Things Hard on Yourself, but in a Good Way: Creating Desirable Difficulties to Enhance Learning’, in Psychology and the Real World: Essays Illustrating Fundamental Contributions to Society (New York, NY, US: Worth Publishers, 2011), 56–64.

- Karen C. Stoiber and Maribeth Gettinger, ‘Multi-Tiered Systems of Support and Evidence-Based Practices’, in Handbook of Response to Intervention: The Science and Practice of Multi-Tiered Systems of Support, ed. Shane R. Jimerson, Matthew K. Burns, and Amanda M. VanDerHeyden (Boston, MA: Springer US, 2016), 121–41, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-7568-3_9.

- Department of Education, Skills and Employment, ‘The Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration’.

- Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs, ‘Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians’.

- Révai, ‘A Review with Case Studies on Australia, Estonia and Singapore’.

- Australian Education Research Organisation, ‘“But That Would Never Work Here” – Does Context Matter More than Evidence?’

- Jordana Hunter, Amy Haywood, and Nick Parkinson, ‘Ending the Lesson Lottery: How to Improve Curriculum Planning in Schools’, Grattan Institute, 2022, https://grattan.edu.au/report/ending-the-lesson-lottery-how-to-improve-curriculum-planning-in-schools/.

- Bartanen, Brendan et al., ‘“Refining” Our Understanding of Early Career Teacher Skill Development: Evidence From Classroom Observations’, 2023, https://doi.org/10.26300/WYKJ-E663.

- Matt O’Sullivan, ‘The Issue of Increasing Disruption in Australian School Classrooms’, text, 2023, Australia, https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Education_and_Employment/DASC/Interim_Report.

- NSW Education Standards Authority, ‘Highly Accomplished Teacher Evidence Guide – For Applicants Working in K-12 Schools’, November 2022, https://educationstandards.nsw.edu.au/wps/wcm/connect/47628e6a-be6d-4263-8686-0854cb61470a/highly-accomplished-teacher-evidence-guide-for-applicants-working-in-k-12-schools.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=.

- Australian Government Department of Education, ‘National Teacher Workforce Action Plan’.

- Jordan Baker, ‘Plan for Tenfold Increase in Top Teachers within the next Three Years’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 14 May 2022, https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/plan-for-tenfold-increase-in-top-teachers-within-the-next-three-years-20220513-p5al9l.html.

- Ingvarson, ‘Development of a National Standards Framework for the Teaching Profession’.

- Australian Government Productivity Commission, ‘Review of the National School Reform Agreement’, December 2022, https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/school-agreement/report/school-agreement-overview.pdf.

- Audit Office of New South Wales, ‘Regional, Rural and Remote Education’, 10 August 2023, https://www.audit.nsw.gov.au/our-work/reports/regional-rural-and-remote-education.

- Joanne M. Van Boxtel, ‘Seeing Is Believing: Innovating the Clinical Practice Experience for Education Specialist Teacher Candidates With Video-Based Remote Supervision’, Rural Special Education Quarterly 36, no. 4 (1 December 2017): 180–90, https://doi.org/10.1177/8756870517737313.

- Sarah Duggan, ‘Mandates and Scripted Lessons: Have Teachers Lost Their Autonomy?’, 30 August 2022, https://educationhq.com/news/mandates-and-scripted-lessons-have-teachers-lost-their-autonomy-127568/.

- Ochre Education, ‘Partnering with Catholic Education Canberra Goulburn (CECG) to Offer Nearly 50 New Sequenced F-6 Maths Lessons – Ochre Education’, 25 October 2022, https://ochre.org.au/nearly-50-new-sequenced-f-6-maths-lessons-and-hundreds-of-free-high-quality-evidence-aligned-resources-now-available/.

- Hunter, Haywood, and Parkinson, ‘Ending the Lesson Lottery’.

- Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership, ‘Accreditation of Initial Teacher Education Programs in Australia: Standards and Procedures’, 2017, https://www.aitsl.edu.au/tools-resources/resource/accreditation-of-initial-teacher-education-programs-in-australia—standards-and-procedures.

- Révai, ‘A Review with Case Studies on Australia, Estonia and Singapore’.

- Révai.

- Révai.

- Dinham, ‘Issues and Perspectives Relevant to the Development of an Approach to the Accreditation of Initial Teacher Education in Australia Based on Evidence of Impact’.

- Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership, ‘Australian Professional Standards for Teachers’.

- Scott, ‘Strong Beginnings’, 9.

- Scott, 9.

- Jenny Gore, ‘Teaching Degrees Are Set for a Major Overhaul, but This Is Not What the Profession Needs’, The Conversation, 7 July 2023, http://theconversation.com/teaching-degrees-are-set-for-a-major-overhaul-but-this-is-not-what-the-profession-needs-209223.

- Debra Hayes, ‘Political Incursion into Teaching the Teachers Is a Hard Lesson’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 7 July 2023, https://www.smh.com.au/education/political-incursion-into-teaching-the-teachers-is-a-hard-lesson-20230706-p5dmcm.html.

- Scott, ‘Strong Beginnings’, 13.

- Linda Darling-Hammond, Maria Hyler, and Madelyn Gardner, ‘Effective Teacher Professional Development’ (Learning Policy Institute, June 2017), v, https://doi.org/10.54300/122.311.

- Darling-Hammond, Hyler, and Gardner, ‘Effective Teacher Professional Development’.

- Sam Sims and Harry Fletcher-Wood, ‘Identifying the Characteristics of Effective Teacher Professional Development: A Critical Review’, School Effectiveness and School Improvement 32, no. 1 (2 January 2021): 47–63, https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2020.1772841.

- Sims and Fletcher-Wood.

- Sam Sims et al., ‘Effective Teacher Professional Development: New Theory and a Meta-Analytic Test’, Review of Educational Research, 26 December 2023, 00346543231217480, https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543231217480.

- Sims et al.

- Deans for Impact, ‘Practice with Purpose: The Emerging Science of Teacher Expertise.’, 2016, https://www.deansforimpact.org/files/assets/practice-with-purpose.pdf.

- Australian Government Productivity Commission, ‘Review of the National School Reform Agreement’; Lisa Paul, ‘Next Steps: Report of the Quality Initial Teacher Education Review’, Text, Department of Education, 24 February 2022, https://www.education.gov.au/quality-initial-teacher-education-review/resources/next-steps-report-quality-initial-teacher-education-review.

- The University of Newcastle, ‘What Is the QT Model?’, QT Academy, 2023, https://qtacademy.edu.au/what-is-the-qt-model/.

- Peter Matthews, ‘Incremental Coaching in Schools – Small Steps to Professional Mastery: An Evaluation and Guide for Leaders’, August 2016, https://s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/ambition-institute/documents/Incremental_coaching_-_full_report.pdf.

- Matthews, 51.

- Josh Goodrich and Ben Abelman, ‘Steplab – A Professional Development Platform for Schools’, 2024, https://steplab.co/.

- Josh Goodrich and Boguslav, ‘The Evidence and Rationale Behind Steplab | Steplab’, 2022, https://steplab.co/resources/papers/BP0703zw/The-Evidence-and-Rationale-Behind-Steplab.

- Bartanen, Brendan et al., ‘“Refining” Our Understanding of Early Career Teacher Skill Development’.

- Bastian, Lys, and Whisenant, ‘Does Placement Predict Performance?’

- John R Hollingsworth and Silvia Ybarra, Explicit Direct Instruction (EDI); the Power of the Well-Crafted, Well Taught Lesson. (Portland: Corwin Press Inc, 2009).

- Rosenshine, ‘Principles of Instruction – UNESCO Digital Library’.

- Bartanen, Brendan et al., ‘“Refining” Our Understanding of Early Career Teacher Skill Development’.

- North Carolina Professional Teaching Standards Commission, ‘North Carolina Professional Teaching Standards’, accessed 1 February 2024, https://sites.google.com/dpi.nc.gov/ncees-information-and-resource/teachers.

- National Board for Professional Teaching Standards, ‘What Teachers Should Know and Be Able to Do’, 2016, https://www.accomplishedteacher.org/_files/ugd/0ac8c7_25be1413beb24c14ab8f6e78a20aa98f.pdf.

- National Board for Professional Teaching Standards.

- Nanyang Technological University, ‘TE21: Empowering Teachers for the Future’, NTU, 2023, https://ebook.ntu.edu.sg/nie_te21_booklet/full-view.html.

- Department for Education, ‘Teachers’ Standards’, accessed 27 January 2024, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a750668ed915d3c7d529cad/Teachers_standard_information.pdf.

- Department for Education, ‘Early Career Framework’, 29 June 2022, 17, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/early-career-framework.

- Scott, ‘Strong Beginnings’, 95–104.

References

Audit Office of New South Wales. ‘Regional, Rural and Remote Education’, 10 August 2023. https://www.audit.nsw.gov.au/our-work/reports/regional-rural-and-remote-education.

Australian Education Research Organisation. ‘“But That Would Never Work Here” – Does Context Matter More than Evidence?’, 27 September 2022. https://www.edresearch.edu.au/other/articles/would-never-work-here-does-context-matter.

‘Writing Development: What Does a Decade of NAPLAN Data Reveal?’, 2022. https://www.edresearch.edu.au/sites/default/files/2022-10/writing-development-summary-aa.pdf.

Australian Government Department of Education. ‘Education Ministers Meeting Communiqué – December 2023’. Text, 12 December 2023. https://www.education.gov.au/education-ministers-meeting/resources/education-ministers-meeting-communique-december-2023. ‘Education Ministers Meeting Communiqué – July 2023’, 6 July 2023. https://www.education.gov.au/education-ministers-meeting/resources/education-ministers-meeting-communique-july-2023. ‘National Teacher Workforce Action Plan’, 15 December 2022. https://www.education.gov.au/national-teacher-workforce-action-plan.

Australian Government Productivity Commission. ‘Review of the National School Reform Agreement’, December 2022. https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/school-agreement/report/school-agreement-overview.pdf.

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership. ‘Accreditation of Initial Teacher Education Programs in Australia: Standards and Procedures’, 2017. https://www.aitsl.edu.au/tools-resources/resource/accreditation-of-initial-teacher-education-programs-in-australia—standards-and-procedures. ‘Australian Professional Standards for Teachers’, 2018. https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/national-policy-framework/australian-professional-standards-for-teachers.pdf?sfvrsn=5800f33c_64.

Baker, Jordan. ‘Performance Pay, Revamped School Hours: Premier Flags Education Reforms’. The Sydney Morning Herald, 18 June 2022. https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/performance-pay-revamped-school-hours-premier-flags-education-reforms-20220617-p5aula.html. ‘Plan for Tenfold Increase in Top Teachers within the next Three Years’. The Sydney Morning Herald, 14 May 2022. https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/plan-for-tenfold-increase-in-top-teachers-within-the-next-three-years-20220513-p5al9l.html.

Bartanen, Brendan, Bell, Courtney, James, Jessalynn, Taylor, Eric S., and Wyckoff, James H. ‘“Refining” Our Understanding of Early Career Teacher Skill Development: Evidence From Classroom Observations’, 2023. https://doi.org/10.26300/WYKJ-E663.

Bastian, Kevin C., Diana B. Lys, and Waverly R. L. Whisenant. ‘Does Placement Predict Performance? Associations Between Student Teaching Environments and Candidates’ Performance Assessment Scores’. Journal of Teacher Education 74, no. 1 (1 January 2023): 40–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/00224871221105814.

Bjork, Elizabeth Ligon, and Robert A. Bjork. ‘Making Things Hard on Yourself, but in a Good Way: Creating Desirable Difficulties to Enhance Learning’. In Psychology and the Real World: Essays Illustrating Fundamental Contributions to Society, 56–64. New York, NY, US: Worth Publishers, 2011.

Brophy, Jere. ‘Teacher Influences on Student Achievement’. American Psychological Association 41, no. 10 (1986): 1069–77.

Creemers, B. P. M., and L. Kyriakides. ‘Critical Analysis of the Current Approaches to Modelling Educational Effectiveness: The Importance of Establishing a Dynamic Model’. School Effectiveness and School Improvement 17, no. 3 (1 September 2006): 347–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243450600697242.

Creemers, Bert, and Leonidas Kyriakides. ‘Process-Product Research: A Cornerstone in Educational Effectiveness Research’. Journal of Classroom Interaction 50, no. 2 (2015): 107–19.

Darling-Hammond, Linda, Maria Hyler, and Madelyn Gardner. ‘Effective Teacher Professional Development’. Learning Policy Institute, June 2017. https://doi.org/10.54300/122.311.

Darling-Hammond, Linda, and Peter Youngs. ‘Defining “Highly Qualified Teachers”: What Does “Scientifically-Based Research” Actually Tell Us?’, 2002. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X031009013.

Deans for Impact. ‘Practice with Purpose: The Emerging Science of Teacher Expertise.’, 2016. https://www.deansforimpact.org/files/assets/practice-with-purpose.pdf.

Department for Education. ‘Early Career Framework’, 29 June 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/early-career-framework. ‘Teachers’ Standards’. Accessed 27 January 2024. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a750668ed915d3c7d529cad/Teachers_standard_information.pdf.

Department of Education, Skills and Employment. ‘The Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration’, 2019. https://www.education.gov.au/alice-springs-mparntwe-education-declaration/resources/alice-springs-mparntwe-education-declaration.

Dinham, Stephen. ‘Issues and Perspectives Relevant to the Development of an Approach to the Accreditation of Initial Teacher Education in Australia Based on Evidence of Impact’, 1 May 2015. http://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/initial-teacher-education-resources/ite-reform-stimulus-paper-03-dinham.pdf.

Duggan, Sarah. ‘Mandates and Scripted Lessons: Have Teachers Lost Their Autonomy?’, 30 August 2022. https://educationhq.com/news/mandates-and-scripted-lessons-have-teachers-lost-their-autonomy-127568/.

Elliott, Kerry, Pru Mitchell, Hilary Hollingsworth, Charlotte Waters, and Jenny Trevitt. ‘Environmental Scan Topical Areas to Inform a Future Review of the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers’. Final Report, 2020.

Elmore, Richard. ‘Getting to Scale with Good Educational Practice’. Harvard Educational Review 66, no. 1 (1996): 1–27.

Goodrich, Josh, and Ben Abelman. ‘Steplab – A Professional Development Platform for Schools’, 2024. https://steplab.co/.

Goodrich, Josh, and Boguslav. ‘The Evidence and Rationale Behind Steplab | Steplab’, 2022. https://steplab.co/resources/papers/BP0703zw/The-Evidence-and-Rationale-Behind-Steplab.

Gore, Jenny. ‘Teaching Degrees Are Set for a Major Overhaul, but This Is Not What the Profession Needs’. The Conversation, 7 July 2023. http://theconversation.com/teaching-degrees-are-set-for-a-major-overhaul-but-this-is-not-what-the-profession-needs-209223.

Hayes, Debra. ‘Political Incursion into Teaching the Teachers Is a Hard Lesson’. The Sydney Morning Herald, 7 July 2023. https://www.smh.com.au/education/political-incursion-into-teaching-the-teachers-is-a-hard-lesson-20230706-p5dmcm.html.

Hollingsworth, John R, and Silvia Ybarra. Explicit Direct Instruction (EDI); the Power of the Well-Crafted, Well Taught Lesson. Portland: Corwin Press Inc, 2009.

Hunter, Jordana, Amy Haywood, and Nick Parkinson. ‘Ending the Lesson Lottery: How to Improve Curriculum Planning in Schools’. Grattan Institute, 2022. https://grattan.edu.au/report/ending-the-lesson-lottery-how-to-improve-curriculum-planning-in-schools/.

Ingvarson, Lawrence. ‘Development of a National Standards Framework for the Teaching Profession’. Policy brief, May 2002.

Jang, Hyungshim, Johnmarshall Reeve, and Edward L. Deci. ‘Engaging Students in Learning Activities: It Is Not Autonomy Support or Structure but Autonomy Support and Structure.’ Journal of Educational Psychology 102, no. 3 (August 2010): 588–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019682.

Kalyuga, Slava. ‘Expertise Reversal Effect and Its Implications for Learner-Tailored Instruction’. Educational Psychology Review 19, no. 4 (1 December 2007): 509–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-007-9054-3.

Kirschner, Paul A., John Sweller, and Richard E. Clark. ‘Why Minimal Guidance During Instruction Does Not Work: An Analysis of the Failure of Constructivist, Discovery, Problem-Based, Experiential, and Inquiry-Based Teaching’. Educational Psychologist 41, no. 2 (1 June 2006): 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_1.

Martin, Andrew J. Using Load Reduction Instruction (LRI) to Boost Motivation and Engagement. Leicester, UK: The British Psychological Society, 2016. 2016.

Martin, Andrew J., and Paul Evans. ‘Load Reduction Instruction: Exploring a Framework That Assesses Explicit Instruction through to Independent Learning’. Teaching and Teacher Education 73 (1 July 2018): 203–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.03.018. ‘Load Reduction Instruction (LRI)’. In Advances in Cognitive Load Theory, edited by Sharon Tindall-Ford, Shirley Agostinho, and John Sweller, 1st ed., 15–29. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY : Routledge, 2019.: Routledge, 2019. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429283895-2.

Martin, Andrew J., Paul Ginns, Emma C. Burns, Roger Kennett, and Joel Pearson. ‘Load Reduction Instruction in Science and Students’ Science Engagement and Science Achievement.’ Journal of Educational Psychology 113, no. 6 (August 2021): 1126–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000552.

Martin, Andrew J., Paul Ginns, Robin P. Nagy, Rebecca J. Collie, and Keiko C. P. Bostwick. ‘Load Reduction Instruction in Mathematics and English Classrooms: A Multilevel Study of Student and Teacher Reports’. Contemporary Educational Psychology 72 (1 January 2023): 102147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2023.102147.

Matthews, Peter. ‘Incremental Coaching in Schools – Small Steps to Professional Mastery: An Evaluation and Guide for Leaders’, August 2016. https://s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/ambition-institute/documents/Incremental_coaching_-_full_report.pdf.

Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs. ‘Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians’, 2008.

Ministers’ Media Centre. ‘More Support for Teachers to Manage the Classroom’, 2 May 2023. https://ministers.education.gov.au/clare/more-support-teachers-manage-classroom.

Nanyang Technological University. ‘TE21: Empowering Teachers for the Future’. NTU, 2023. https://ebook.ntu.edu.sg/nie_te21_booklet/full-view.html.

National Board for Professional Teaching Standards. ‘What Teachers Should Know and Be Able to Do’, 2016. https://www.accomplishedteacher.org/_files/ugd/0ac8c7_25be1413beb24c14ab8f6e78a20aa98f.pdf.

North Carolina Professional Teaching Standards Commission. ‘North Carolina Professional Teaching Standards’. Accessed 1 February 2024. https://sites.google.com/dpi.nc.gov/ncees-information-and-resource/teachers.

NSW Education Standards Authority. ‘Highly Accomplished Teacher Evidence Guide – For Applicants Working in K-12 Schools’, November 2022. https://educationstandards.nsw.edu.au/wps/wcm/connect/47628e6a-be6d-4263-8686-0854cb61470a/highly-accomplished-teacher-evidence-guide-for-applicants-working-in-k-12-schools.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=.

Ochre Education. ‘Partnering with Catholic Education Canberra Goulburn (CECG) to Offer Nearly 50 New Sequenced F-6 Maths Lessons – Ochre Education’, 25 October 2022. https://ochre.org.au/nearly-50-new-sequenced-f-6-maths-lessons-and-hundreds-of-free-high-quality-evidence-aligned-resources-now-available/.

OECD. ‘Australia | Factsheets | OECD PISA 2022 Results’. OECD, 2023. https://www.oecd.org/publication/pisa-2022-results/country-notes/australia-e9346d47#section-d1e214.

O’Sullivan, Matt. ‘The Issue of Increasing Disruption in Australian School Classrooms’. Text, 2023. Australia. https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Education_and_Employment/DASC/Interim_Report.

Paul, Lisa. ‘Next Steps: Report of the Quality Initial Teacher Education Review’. Text. Department of Education, 24 February 2022. https://www.education.gov.au/quality-initial-teacher-education-review/resources/next-steps-report-quality-initial-teacher-education-review.

Révai, Nóra. ‘A Review with Case Studies on Australia, Estonia and Singapore’. OECD, 2018. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/what-difference-do-standards-make-to-educating-teachers_f1cb24d5-en.

Rosenshine, Barak. ‘Principles of Instruction – UNESCO Digital Library’, 2010. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000190652.

Rosenshine, Barak Victor. ‘Academic Engaged Time, Content Covered, and Direct Instruction’. Journal of Education 160, no. 3 (August 1978): 38–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/002205747816000304.

Savage, Glenn C., and Steven Lewis. ‘The Phantom National? Assembling National Teaching Standards in Australia’s Federal System’. Journal of Education Policy 33, no. 1 (2 January 2018): 118–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2017.1325518.

Scott, Mark. ‘Strong Beginnings: Report of the Teacher Education Expert Panel’, 30 June 2023. https://www.education.gov.au/quality-initial-teacher-education-review/resources/strong-beginnings-report-teacher-education-expert-panel.

Sims, Sam, and Harry Fletcher-Wood. ‘Identifying the Characteristics of Effective Teacher Professional Development: A Critical Review’. School Effectiveness and School Improvement 32, no. 1 (2 January 2021): 47–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2020.1772841.

Sims, Sam, Harry Fletcher-Wood, Alison O’Mara-Eves, Sarah Cottingham, Claire Stansfield, Josh Goodrich, Jo Van Herwegen, and Jake Anders. ‘Effective Teacher Professional Development: New Theory and a Meta-Analytic Test’. Review of Educational Research, 26 December 2023, 00346543231217480. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543231217480.

Stoiber, Karen C., and Maribeth Gettinger. ‘Multi-Tiered Systems of Support and Evidence-Based Practices’. In Handbook of Response to Intervention: The Science and Practice of Multi-Tiered Systems of Support, edited by Shane R. Jimerson, Matthew K. Burns, and Amanda M. VanDerHeyden, 121–41. Boston, MA: Springer US, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-7568-3_9.

The University of Newcastle. ‘What Is the QT Model?’ QT Academy, 2023. https://qtacademy.edu.au/what-is-the-qt-model/.