Foreword

The average family with dependent children today faces critical financial problems. Mothers increasingly find it necessary to enter the workforce to keep the family’s standard of living at a level which satisfies the needs of their children. Not surprisingly, our fertility rate is the lowest in our history and the welfare and socialisation of children is at a low ebb. Fundamental to the family’s current financial problems are radical changes to the manner in which the costs of raising children are acknowledged in the tax and welfare systems today, compared with a generation ago.

The beginning of the century saw the introduction, in Australia, of a centrally-determined industrial wages system predicated on the proposition that an adult male wage (the Basic Wage) should be sufficient to support a dependent wife and three children. At mid-century, official recognition that dependent children should be taken into account in incomes policy was adapted to increasing taxation by introducing tax deductions for major expenses associated with raising children. In the last three decades, however, official policy has shown ambivalence regarding the status of children within the tax/welfare system. The presence of children in a household is now given only selective recognition in welfare policy and, in comparison with the past, minimal consideration in the tax system.

Taxation systems in most developed countries have, in the last half century, changed, and changed again, both in the principles and practice of family taxation. Behind the changes have been oscillations in convictions about the the proper unit of taxation—whether it should be the individual or the couple/family—and of the propriety of giving recognition to expenses incurred on behalf of children in a ‘fair’ system. There has been a marked shift in two directions, reflecting and precipitating profound changes in the economic and sociocultural life of the family—a shift of tax burdens, proportionally, from taxpayers without to taxpayers with dependent children, and of income support from families with children to the various categories entirely dependent on welfare. The movement away from family income support is especially marked for middle-income families (Steuerle 1997).

There is a theory in economics that justifies this situation on the grounds that taxation should no more alleviate the costs of rearing children than it does the costs of purchasing any other good, such as a boat. To have a child is, in this view, to voluntarily acquire a ‘private good’ for one’s own satisfaction and, it is argued, cannot justly impose an obligation on others to subsidise one’s consumer choice. The distinguished economist Henry Simons gave classic expression to this perspective when he said: ‘It would be hard to maintain that the raising of children is not a form of consumption on the part of parents.’ (Simons 1938: 140)

A complete and detailed answer to this position is outside the scope and intentions of this study, but a number of factors relevant to accepted tax and welfare considerations argue against its face value acceptance.

First, income-sharing within families, if combined with the taxation principle that income should be taxed in the hands of the beneficiary of that income, indicates that a component of any household income should be imputed to each family dependent for taxation purposes. This principle underlay the old system of tax deductions for family members.

Second, the principles of horizontal equity and ability to pay require that the size of a household be taken into account in determining its tax contribution.

Third, as the state expects parents to care for their children and there are penalties for those who abandon, neglect or abuse their children, the state should not establish conditions which impede the capacity of parents to fulfil those obligations. When parents fail or die, the state is ‘parent’ of last resort, and must find the funds to meet that responsibility in tax revenue. Consideration of the immense expense and impracticability of the state caring for all children demonstrates the efficiency of ensuring that families retain their economic capacity to rear offspring.

Fourth, there is no inherent inequity in child tax concessions between those with or without dependents at a particular point in time if we take a life-cycle view of taxation benefits and liabilities. At some time in our lives we are all child dependents and we all, therefore, share in tax concessions made available to families. Temporal and intergenerational long-sightedness is required in the assessment of tax equity.

Fifth, raising children is arguably ‘a form of production’ rather than ‘consumption’, and all societies have, as a condition of their survival, an interest in supporting the successful production of children. Children have societal and not just personal utility. This utility can fail to materialise if parenting is undermined.

Over the last two decades in Australia, multiple problems of child neglect, poor education, crime, and low fertility have become ever more manifest, demonstrating the scope for uncertainty in the renewal of human capital. Similar developments both in family taxation and in family functioning have occurred contemporaneously in the United Kingdom, the United States and elsewhere. These signs of the family’s failure are almost certainly in part due to novel disabilities and disincentives created by changes in our tax and welfare systems in the course of the 1980s.

The history of family taxation in Australia, and the character of its latter-day vicissitudes, are the concern of this study. An understanding of the past and the linkage of policy changes to subsequent outcomes shed light on possible reparative strategies for the future. A careful consideration of the wrong directions taken indicates the need to embrace principles in direct opposition to the modern categorisation of the bearing and rearing of children as a form of ‘private consumption’.

Barry Maley, Director, Taking Children Seriously programme, The Centre for Independent Studies

The family income problem

It cannot be disputed that a family unit consisting of husband, wife, and children requires a higher disposable income than does a single person without dependents if it is to maintain a comparable standard of living for its members. An income that means wealth for a single person will leave a family of five somewhat short of comfortable. A comfortable income for a single person will maintain a family in little more than poverty. This is obvious. What is not necessarily obvious is that herein may reside an inherent problem for income distribution in industrial societies. The interactions of wage-control, taxation and family welfare payments in the history of 20th century Australia indicate a continuing need for family income protection and support.

In the late 19th century, when no specific provision for families was made in wages, tax or welfare, poverty was identified with having dependent children in a family (Rowntree 1901), and a great deal of charitable work was generated to meet their condition of need. In Australia, the first 20th century appearance of a balanced solution to the family income problem came with the Harvester Judgment of 1907. This introduced, at the national level, a regulated and indirect method of wages manipulation to meet family needs, with provision for higher ‘family’ earnings than for single (child-free), on a roughly category basis.

The Basic Wage for an adult male wage earner, who was expected to be a family man, was the benchmark. There were progressively lower rates of pay below the average age of marriage, which was in the upper 20s for much of the century. There were also lower rates based on sex, on the grounds, generally correct at that time, that women earners were without dependents.

An alternative to differentiating wages according to putative family earner status is for the tax system or welfare payments to take on the role of redistribution according to the same principle. This was the major course taken from the 1950s to the 1970s. Child Endowment was initiated in the 1940s as a response to the increasing taxation of moderate wages during World War II, and was followed in the 1950s by the introduction of a comprehensive assortment of tax deductions and rebates predicated on family dependency. With redistribution via the tax system well-developed, the use of the Basic Wage as a differential for family and dependent-free earners was, in the course of the 1960s and 1970s, largely abandoned. The age gradient was drastically diminished and the sex differential was formally eliminated.

The need to support family incomes as such appeared to be forgotten in the 1980s. Between 1975 and 1980, the tax deductions which had provided for the family were withdrawn, and increased Child Endowment, now called Family Allowance, became the chief means of family support. But from the early 1980s, the value of the Family Allowance became, with inflation, increasingly unrealistic, while families paid tax at the same rate as other taxpayers at equivalent wage or salary levels.

The effect of the abandonment of family income protection was to throw the family into a state of financial crisis. This has since been handled piecemeal, via proliferating but selective welfare payments which are ‘targeted’ so that only those at the lowest levels of income receive realistic recognition of the costs of their dependent children. As we shall see, because redistribution now occurs from higher to lower incomes regardless of the burden of child dependency, a vicious cycle has been created which drives poverty progressively up the family income scale.

In the era of Child Endowment and tax deductions, policy assumed that families, like earners without dependents, should retain a range of incomes, reflecting the socioeconomic status of the earner. A couple’s decision to rear a family should not condemn them to a standard of living utterly different from their current one. By contrast, the effect of tax and welfare policy today is that a large proportion of families must raise children at the lowest common level of welfare-provided income, regardless of initial differences in earner status.

Family income protection for most of the present century was so contrived that family income could essentially be provided by one wage-earner within the family unit, the husband and father, while the wife and mother took primary responsibility for the rearing of children and for the domestic economy. Only in the last two decades, largely in response to economic pressures resulting from the abandonment of policies protective of family income, have mothers entered the workforce in substantial numbers, thereby providing a second source of needed family income.

The abandonment of universal family income protection in the 1980s was accompanied by the introduction of childcare funding for working mothers of pre-school children. As a result, the balance in child-rearing choices was changed. The Child Endowment and tax deductions of earlier years can be seen as a policy enabling the family to care personally for its children. Their substitution by childcare funding of various kinds can therefore be seen as a policy of discouraging care by the mother and promoting extra-familial or state child-rearing. This change was implemented despite the fact that most Australians continue to believe that mothers of pre-school children are better at home full-time, and that those of older children should work at most part-time (Evans 1995).

Childcare payments have become increasingly generous since the time of their introduction, but equivalent support has not been made available for mothers who care for their children themselves. This suggests the espousal of a principle that only if parents are willing to relinquish the care of their infant children to strangers so that both parents can work in the market economy, are they worthy of income protection.

It is now questionable whether this policy is in the interests of the children themselves, of families, or of the society at large. There is growing sociological, psychological and epidemiological evidence that as the family has moved away from the earlier model of the father as breadwinner and the mother as full-time child rearer, the socialisation of children and their personal well-being have suffered (Devery 1991; Bennett 1994; Maley, Berger, Morgan et al. 1996; Sullivan 1997).

Thus the family’s need for a higher disposable income, in conjunction with the sociocultural advantage of domestic specialisation by the mother, appears to create something of a make or break nexus for the flourishing of industrial and post-industrial society. Satisfaction of the problem of the ‘living wage’ for families is necessary to enable parents to raise first-class future citizens, and requires no more than recognition of all family members as citizens and life-cycle taxpayers.

The analysis that follows demonstrates the degree of our current failure to achieve this requirement and plots the errors of policy which have brought us to this condition. It thereby elucidates the criteria that must be observed if we are to re-achieve adequate family income protection.

Part A

The current situation and how we got here

A brief history of taxation 1890–1950[1]

The income needs of both family and child-free earners were, on the whole, satisfactorily accommodated throughout the first 70 years of the 20th century in Australia. To understand this achievement, it is necessary to review briefly our taxation history.

Taxation in Britain in the 18th and 19th centuries was largely a consumption tax on luxury items, thus sparing those with moderate and low standards of living. But from the mid-19th century taxes were extended beyond luxury goods to include essential food items—flour, sugar, rice and tea—and also alcohol and tobacco, the luxuries of the poor as well as the wealthy. Income tax and land tax began to assume importance in England from the 1870s, but at first only touched the affluent. They were proportional—‘flat rate’—taxes, which nevertheless meant that the wealthier pay more than the less wealthy by virtue of larger income or property.

Following in this pattern, customs duties were the mainstay of Australian taxation until World War I. Customs and excise revenue was allocated to the Commonwealth Government at Federation in 1901, with an obligation to disburse at least three quarters of its yield to the States. South Australia introduced the first real income tax in Australia in 1884. It was progressive—Australia is noted for its early use of progressive taxation—with rising rates to an upper limit, and had a high threshold for exemption of ₤300, so that only high income earners were taxed. Income tax was introduced in New South Wales and Victoria in 1895. Tax on company income and dividends also appeared in these decades.

Taxation in the 18th century was justified in terms of benefit received. As government was largely concerned with protection of property, this justified the practice of taxing only the wealthy. But in the 20th century, with the growth of Labour politics, government began to be seen as an instrument of social intervention with obligations to all levels of society. ‘Ability to pay’ became the generally agreed principle for allocation of taxation to yield the larger revenue required for these purposes, and hence the commitment to progressive taxation. This reflected the egalitarian politics of the time, and became ingrained in Australian culture. In keeping with this principle, the Commonwealth government under Labour introduced a national land tax to fund Old Age Pensions in 1910.

In 1915, during World War I, the first national income tax was introduced. In 1928, the threshold for Commonwealth income tax was ₤300 p.a., and the States also levied income tax with a threshold of ₤200, at a time when the Basic Wage was ₤52 per annum. Thus incomes at up to four to six times minimum wages paid no tax at this time. In 1940, during World War II, the Commonwealth threshold was lowered, under Labour, to ₤200 p.a., still more than three times the Basic Wage. In 1942, the states yielded all income tax to the Commonwealth, and in 1943, in response to the cost of war, the threshold was reduced to ₤105 p.a., less than double the basic wage. (Smith 1993)

The Basic Wage: protecting family income

‘The principle of a living or basic wage was propounded as far back as 1890 by Sir Samuel Griffith, Premier of Queensland, but it was not until the year 1907 that a wage as such was declared by a Court in Australia. The declaration was made by Mr Justice Higgins, President of the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration, who defined the standard of a “fair and reasonable” minimum wage for unskilled labourers as that appropriate to “the normal needs of the average employee living in a civilised community”. The rate declared by the President in his judgment (known as the ‘Harvester Judgment’) was . . . the amount considered reasonable for “a family of about five” (ABS Labour Report 1968 & 1969:143).

The judgment of Justice Higgins in 1907 that the Basic Wage ought to provide for the needs of a man and his wife and three children living in ‘frugal comfort’ was made viable by a system of wage inequality, together with the absence of income tax even at quite comfortable levels of income. Prior to the 1950s, the female adult wage was generally about 55% of the male adult wage, and there was a steep gradient in youth wages (which persisted into the 1970s) reaching down from the mid-twenties to the early teens. Thus a differentiation in final income between individual and family earners was achieved, at some social cost in atypical family situations, using wage differentials based on age and sex roles, without resort to redistribution via tax exemptions or welfare disbursements. Widows pensions were introduced by the States in the 1920s and by the Commonwealth in the 1940s, so that women did not have to support families on single-earner wages.

Initially, the Basic Wage was adjusted quarterly in proportion to the retail price index, and on it were built the various awards for skilled occupations. During the late 1930s and 1940s, however, the principle on which it was assessed changed subtly from simply reflecting the living costs of a family to incorporating (via ‘prosperity loadings’) ‘the highest amount which the economy could sustain’ (Smith 1993). However, its value soon became less than was required to provide adequate living standards for a Harvester Judgment family of five.

Virtually from the moment income tax bit into even moderately high male wages, the need for palliative action on behalf of family incomes became apparent. State income taxes in the late 1920s began at four times the Basic Wage, and child endowment schemes began in the States at about the same time. When the Commonwealth brought income tax down to moderate income levels in 1940, it was in tandem with a National Child Endowment scheme established the following year. To fund Child Endowment, the Menzies government introduced payroll tax, which stipulated that 2.5% of employers’ payrolls went to a National Welfare Fund for Child Endowment. This was, of course, a new strategy for the redistribution of earned income to family earners.

The Commonwealth’s introduction of Child Endowment coincided with a pegging of the Basic Wage by the Arbitration Commission, thus demonstrating the impact of wage and taxation levels on the need for other means of protection of family income. All earners were taxed at the same rate, but Child Endowment allowed the Basic Wage to be set at a lower level than was adequate for a family of five. Child Endowment was not paid for the first child, indicating that the Basic Wage was now considered sufficient for a family with one child. It was paid on a per child basis and thus marked a first step in the direction of fine tuning family income protection to family size.

The Horizontal Equity Principle 1950–1975

In 1950, the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration raised the adult female basic wage to 75% of the male rate. Conversely, the adult male Basic Wage was no longer pitched sufficiently above the requirements of a single person to be adequate for an average-sized family. In the same year a Child Endowment payment of 5/- for the first child in a family was introduced, in addition to the 10/- per subsequent child to the age of 16, but nevertheless the value of Child Endowment was not maintained in a period of relatively high inflation. For a family with two children, it represented about 7.5% of adult male Average Weekly Earnings (AWE). Further measures were needed to provide adequate family income protection.

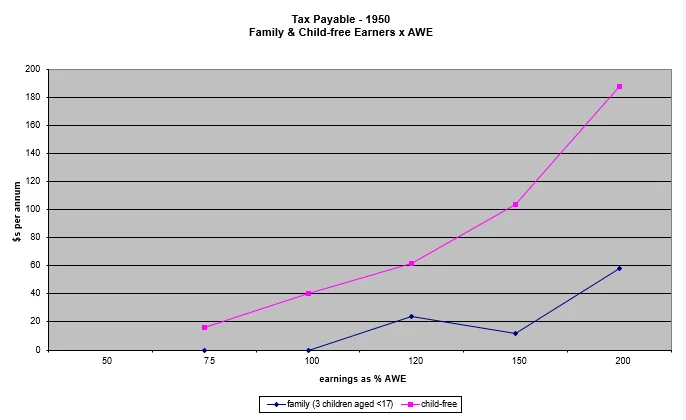

Income tax was at that stage highly progressive. In 1955, for example, there were 18 rising marginal rates above the level for Average Weekly Earnings, beginning at 19% and rising to a top marginal rate of 67% (the equivalent of about 19c and 67c in the dollar, respectively). The Liberal Government of the period introduced an array of deductions geared to the actual financial costs of dependents. Deductions (which reduce gross taxable income), set at ₤104 for a dependent spouse and ₤65 for each dependent child aged less than 16, were introduced. Additionally there were deductions with moderate maximum levels for costs of medical, dental and chemists’ bills, health and life insurance premiums, council and water rates, educational expenses (fees, books, clothing)—all essential major expenses which are multiplied by dependents.

The outcome of the combined use of progressive marginal rates and family-related tax deductions was that high-income child-free earners paid more tax than high-income family earners, who paid more tax than low-income family earners, who paid less tax than low-income child-free earners.

This system virtually eliminated taxation for average-sized families earning up to double the Basic Wage. Tax deductions plus Child Endowment meant that, in 1950, a married man on Average Weekly Earnings with two children paid tax at an effective average rate of minus 3.3%. A man in the same situation on three quarters Average Weekly Earnings paid minus 7.5% (see Appendix 2). In the absence of taxation, the Basic Wage was adequate for average family needs. Deductions for dependents were raised regularly in response to inflation, but nevertheless their value fell somewhat over the years. As higher education became more common, the maximum age for deductions for dependent children was raised. The economic viability of the family was also promoted by low home loan interest rates set by the Commonwealth (3.9% in 1952, 4.5% in 1953-55, and 5% in 1956-60) and the direction of considerable funds into Building Societies for funding of home loans (Murphy 1995).

As the 1950s and 1960s progressed, the adequacy for families of the Basic (later the Minimum) Wage became increasingly dependent on the operation of these tax exemptions. Child Endowment was allowed to languish and there was no increase in payments until the early 1970s. The comprehensive package of deductions went a long way towards ensuring similar living standards for average child-free earners and families, and an income tax system which nominally reached into the lower levels of earnings was made compatible with adequate family income protection.

To begin with, tax rates for most income levels were low compared with present-day standards. The tax taken from an earner without dependents rose dramatically in the 20 year period from 1955 to 1975. The net income tax paid by an earner without dependents on Average Weekly Earnings rose from 6% in 1955 to 9% in 1965, to 17% in 1975. The net tax paid by an earner without dependents on twice Average Weekly Earnings rose from 14% in 1955, to 20% in 1965, to 34% in 1975 (see Appendix 2).

Average-income families were well-protected from this rise, but by 1975 higher-income families were paying tax at a high rate by the standards of previous decades. A Harvester Judgment family (three children) on Average Weekly Earnings, and counting in Child Endowment, paid minus 7%, minus 5%, and 3% in these same years, while the contributions from a family of five on twice Average Weekly Earnings were minus 1%, 3%, and 22%, respectively. At all levels the differential between child-free and family taxation was considerable, and for both families and child-free earners, despite progressive taxation, final income rose with rising earnings.

The social ethic behind the Menzies approach to family income protection, seen in the choice of tax differentials rather than direct disbursements, can be construed as nurturing the financial independence of the family unit and emphasising that, for the family as well as the earner without dependents, income should derive directly from work effort and achievement. This is in marked contrast with today’s welfare approach which compensates entirely for large differences in earned income among families, obliterating much of the relationship between personal effort and income.

Losing the balance: the removal of horizontal equity 1970–1985

In the early 1970s, changes occurred in wage structures and attitudes to the family that eventually led in the 1980s to the use of welfare rather than wages and taxation as a ‘solution’ to the family income problem.

Over the five years from 1969 to 1974, the principles and practice of differing rates of pay for males and females were philosophically rejected and bureaucratically eliminated. In 1969, the Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Commission endorsed the principle of equal pay for equal work under federal awards. Its introduction was to be gradual, and completed by January 1972. In the National Wage Case of 1974, adult females under Federal awards were granted the same minimum wage as adult males, to be phased in in three stages, and this was shortly replicated by State tribunals. The differentials between youth and adult wages were also greatly diminished.

The equal pay reform meant the elimination of the Harvester ‘living wage’ solution of ensuring higher incomes for families than for individuals without disrupting the work value/wages relationship as a total package (and so makes recent calls for a ‘living wage’ like that of 1907 entirely unrealistic1). Initially it created an unfavourable costs to productivity ratio, as female wages were brought into parity with male, rather than both being set at an intermediate mean. A sharp rise in unemployment followed, together with a large growth in part-time employment and the introduction of employment practices which sought to avoid the on-costs of wages (e.g. employing under casual conditions). To avoid further increases in unemployment, the government adopted an accommodating monetary policy, and inflation followed.

To add to these problems, the Whitlam government’s welfare and social programme was expensive and rising unemployment increased its cost. In the following years, taxation rose steeply, affecting both business and workers. Higher revenue from PAYE income tax was achieved by default as inflation and bracket creep drove high rates of taxation further and further down the income scale. Taxation policy from 1975 to 1985 was acknowledged as being in a state of increasing confusion (Wilkes 1980). Smith comments:

By the mid-1970s . . . the relentless increase in income taxation was destabilising the economy . . . Now not only professionals but wage earners too, were raising their wages demands to anticipate the effects of the income tax system on after-tax wages . . . Higher wages paid by employers in turn added to unemployment, and in particular, inflation.

By the 1980s, the Australian taxation system was . . . widely perceived to be economically destructive in its effects on production, consumption, saving and investment decisions. The tax burden . . . shifted substantially towards those with a lesser capacity to pay . . . (Smith 1993: 105, 97)

In 1980, the number of marginal rates was reduced to three and rates at the top end of income were reduced from 60c to 48c in the dollar in an attempt to reduce tax evasion (Matthews 1980). But middle and low incomes now attracted tax rates originally designed for the comparatively wealthy. In 1950, a salary attracting the highest marginal rate was 32 times or 3,200% AWE, and in 1960, 1400% AWE, but in 1980 the highest marginal tax rate was imposed at only three times or 300% AWE. Australia was close to proportional taxation, and the percentage of their wages taken from relatively low income earners had increased dramatically.

Re-emergence of the family income problem

Tax deductions for dependents and family expenses, the then major source of family income protection, were largely withdrawn between 1975 and 1980. The shift in the taxation burden towards lower levels of earnings as a result of bracket creep made protection of family incomes increasingly necessary, but in fact the movement of policy was in the opposite direction.

The use of deductions from taxable income was criticised at this time because the value of exemptions for a given expenditure on dependents was thereby higher for higher-income than for lower-income earners—an effect of their higher maximum tax rates. (Nevertheless, in a context of progressive tax rates, higher income earners with families still paid more tax than lower income earners with families.) In 1976, the per-child tax deductions were abolished and in compensation Child Endowment, renamed Family Allowance, was raised considerably—for example, from a little under $200 p.a. to over $700 for a family with three children (see Appendix 2, Table 3). The value of per-child tax deductions for a similar family with average earnings had been about $720 p.a., so such a family was about $200 p.a. worse off.

The Family Allowance, as a flat-rate per-child payment without an upper income-threshold, was of equal value for high- and low-income families. At the same time, the dependent spouse deduction was changed to a rebate (a direct deduction from tax), also making it of equal value at all income levels. By 1980, the remaining deductions for family expenses (for educational, medical and housing costs) had been removed.

A major effect of the change from tax deductions to Family Allowance was an overall diminution in family income protection, in that the tax exemption for middle- and higher-income families, in comparison with equivalent earners without dependents, was reduced. Families as a whole were left carrying a far greater percentage of the tax burden than had previously been the case. The gain to low-income families was not equal to the loss by middle- and high-income families, and the balance of contribution to taxation by family and child-free earners was shifted to benefit the latter.

If the intention was to pay for the rising cost of Social Security and other costs of government and to relieve the tax load on business by increasing revenue from personal taxtation, then this could have been achieved by increasing effective taxation for all taxpayers, rather than allowing the bulk of the increase to settle on family earners. Tax paid by earners without dependents on Average Weekly Earnings rose from 17% in 1975 to 24% in 1985, and on twice Average Weekly Earnings from 34% to 38%. But net tax (i.e. deducting the value of Family Allowance) paid by average family earners (with three children) on AWE rose from 3% to 13%, and on twice Average Weekly Earnings from 22% to 33%. Thus the differential between family and individual net incomes diminished at average income levels, and at higher levels became insignificant. This change was introduced without major public debate, and most Australians are unaware of its role in the financial difficulties with which middle-income families are still struggling.

Like Child Endowment before it, the Family Allowance was not indexed to the cost of living, and so provided a less resilient form of protection for the family than had the previous wage differentials and tax deductions. The Hawke Accord of the early 1980s promised the lowering of taxes in balance with lesser wage increases. But the lowering of tax rates was at the higher income levels, and did nothing specifically for family earners, whose taxes rose. In deference to family income protection, the pegging of wages by the Arbitration Commission coincided with a rise in the Family Allowance. But nevertheless the Family Allowance increased only 50% (Australian Bureau of Statistics Year Books), while Average Weekly Earnings rose 65%, between 1980 and 1985 (Australian Bureau of Statistics Labour Statistics).

For families, the new tax arrangements spelt financial difficulties. For those with aspirations to a family, the need to provide in advance was increased by the reduced prospect of assistance later, and this showed itself demographically in the deferral or abandonment of family formation. The average age of mothers at the birth of a child rose by five years in the course of the 1970s and 1980s, while the average age of fathers rose by six years, and the lifetime birth rate fell from 2.7 to 1.9 children per woman.

In existing families, increasing numbers of mothers entered the workforce, mostly part-time, to bolster family incomes. The total percentage of women in employment rose, and the composition of the female workforce changed, from the majority being younger women working full-time before having families, to a high proportion of older married women in part-time employment, whose wages supplemented their husbands’ earnings.

Feminists with policy influence opposed any measures to relieve the family’s financial troubles, other than provision of childcare assistance for mothers joining the workforce. This was in furtherance of their goal of equal employment levels for men and women as a prerequisite of female equality. Nevertheless, the desperate need of lower-income families on this regime became increasingly obvious, and child poverty emerged as a major issue for the first time in the 20th century. The next half decade saw the transformation of universal family income protection into welfare for poor families. In the process, lower income families were artificially pauperised.

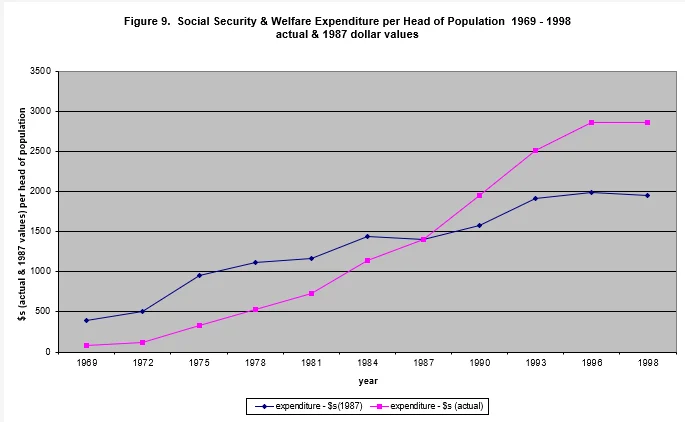

Tax ebb and welfare flow 1985-1997

Changes to tax rates in the late 1970s and early 1980s diminished rather than increased vertical equity. In the aftermath of the Hawke Tax Summit of 1983, and of the Social Security Review of 1985-88, the number of marginal rates of taxation was raised slightly to five, but the highest rate applied at only 170% (less than double) Average Weekly Earnings. These conditions have more or less persisted, with a reduction to four rates and a top rate of 47c in the dollar in 1996/7, until the introduction of the GST.

Bracket creep continued to bring more middle-income earners into the highest taxation bracket, and the top rate applied at a mere 1.5 or 150% AWE in 1990, and in 1997 at 140% AWE (at $50,000 p.a.). To compound the problem of high tax at low incomes, the tax threshold, which in 1980 was set at about 30% AWE, fell to 18% AWE in the latter 1980s, and by 1997 had fallen further to 15% AWE (Tax Return Forms ‘S’ and Australian Bureau of Statistics Labour Statistics). For the majority of earners, taxation became virtually proportional, and in keeping with this development, the Medicare Levy, introduced in 1983, was proportional from the beginning.

‘With the focus of wage policy shifting to the “social wage”, the government explicitly linked wages, taxes and social security measures,’ says Smith (1993: 111). But in fact, policies for family income protection moved from the wage and tax to the welfare system, and were concentrated on a limited range of the lowest incomes. The concern moved away from the family as such to a focus on relief of poverty via welfare income.

Incomes policy in the 1980s, influenced by the report People in Poverty (Henderson et al. 1970) and the development of a ‘poverty line’ as an index, concentrated on bringing the lowest incomes in the community up to a base common level solely by the use of welfare payments. Initially these lowest incomes were the welfare pensions and benefits of the aged, the unemployed and sole parents. But in the course of the 1980s, with the withdrawal of family tax deductions, the post-tax incomes of increasing numbers of employed families fell below benefits levels and required welfare subsidy. The devastating effect on lower-income working families of high taxes combined with the withdrawal of family tax deductions and rebates prompted the Hawke Labor government’s promise of ‘no child in poverty by 1990’, a promise that has proved impossible to fulfil by the method chosen.

Welfare spurns the average working family

In 1985, the sole relic of universal family income protection was the Dependent Spouse Rebate (DSR), the continuance of which deferred to the needs of older couples rather than of child-rearing families. Family Allowances were the only remaining universal measure of family income protection. By 1990, despite inflation, the Dependent Spouse Rebate had not changed, and the Family Allowance, which had risen only slightly, was no longer universal: families earning about 200% AWE and above were no longer eligible.

To the original Family Allowance a whole battery of welfare-type Family Payments was added, allocated on a per child basis and targeted at low-income families. The family on 50% AWE (unlikely to represent full-time earning) with three teenagers, for example, was now eligible for an Additional Family Payment double that of the Basic Family Allowance, but this was not available to families on Average Weekly Earnings and above. The same family was also eligible for rent assistance and Austudy payments equivalent to three times the Basic Family Allowance. A similar family on Average Weekly Earnings received only an Austudy payment of less than the Basic Family Allowance for a student child aged over 16, while one on 120% AWE received none of these considerations. Both the latter families were required to pay in full the Medicare levy, from which the family on 50% AWE was now exempt.2

As the 1990s progressed, ever more pervasive welfare payments were required to maintain an ever higher proportion of families at a poverty line which many of the new recruits fell below only because of taxation of their earnings: ‘churning’ had become a systemic problem. By 1995, the disparity in aid to families at different income levels had increased. All families in which the mother was not earning were eligible for the Home Child Care Allowance, which had replaced the Dependent Spouse Rebate for families with children. But the Family Allowance had actually fallen in value for an eligible family with teenage children, and the family on Average Weekly Earnings was still not eligible for the Additional Family Payment, while its Austudy entitlement was only half that of a family on 50% AWE. In addition to Austudy, the family on 50% AWE received an Additional Family Payment of four times the Family Allowance and rent assistance at twice its value (Department of Social Security 1995). In 1990, a family on 50% AWE received four times the amount received by a family on AWE, and in 1995, three times as much. In 1990 it received six times the amount received by a family on 200% AWE, and eight times as much in 1995. (see Appendix 2, Table 3)

Lobbying by single-income families, comparing their unsubsidised situation with that of two-income families receiving childcare payments, resulted in some tax concessions for families with the return of a Liberal government in 1996, but the differential in tax paid by family and child-free earners remained small for average earnings and above, and unrealistic in relation to family costs. Although these many welfare payments to families represent considerable income transfer on behalf of children, the redistribution is almost exclusively in favour of low-income families, and is away from middle-income family earners as well as from earners without dependents.

Effect on average and higher family incomes

Household Expenditure Survey data for 1993/4 (Australian Bureau of Statistics 1996) show that, in total, couples with children paid as much in taxes as they received in government benefits. Large sections of the family earner group received almost nothing from this overall sum. Most of this family income support went to semi- or unemployed families as welfare benefits, not as income protection for earning families.

Between 1985 and 1995, the net tax taken from the family on Average Weekly Earnings steadied percentagewise, and even fell somewhat. But the small differentials between family and child-free earners at middle and higher income levels remained. The family with three children on 120% AWE in 1995 lost 20% of its income in tax, compared with 26% for an earner without dependents on the same income. (This compared with a 4% gain for the family and an 11% loss for the individual in 1965). And the family on 200% AWE lost 32% of its income in tax compared with a very similar 35% for an equivalent child-free earner.

In the course of the 1980s, family fiscal and welfare policy was shaped to encourage maternal employment as the only means of raising family spending power to match socioeconomic expectations. Families ineligible for extra Family Allowances were eligible for increasingly generous childcare funding in the 1990s, and the use of childcare over this period rose from 46,000 Commonwealth funded places in 1983 to 301,000 in 1996 (Australian Bureau of Statistics Year Books). The percentage of families with both parents in full-time work was 20% in 1988 and 24% in 1990 (Australian Bureau of Statistics Australian Social Trends).

Nevertheless, in a context of heavy taxation, the gains from maternal employment at lower income levels were inadequate for needs. The adoption of a system of targeted welfare, with payments withdrawn as total family earned income rose, meant that in a family with paternal wages of around Average Weekly Earnings, income brought in by the mother was of little benefit unless it was sufficient to bring total family income to well above the income ceiling for welfare benefits (between 100% and 120% AWE, depending on size of family). Considerable workforce participation by the mother was necessary to gain any advantage.

By the mid 1990s, after tax had been taken out and welfare paid, very little difference in disposable income technically remained for families across the range of earnings from 50% to 120% AWE, which takes in at least 75% of Australian families. Disposable incomes of ‘Harvester’ families across this range hovered just above the Unemployment Benefit for the same family. Where taxation deductions once provided relief across the full range of family incomes, targeted welfare payments were directed only at raising the lowest incomes to average levels.

Welfare policy has narrowed the focus of family income protection to one of poverty relief. The broader canvas of taxation policy, which nominally adjusts to ability to pay, leaves the factor of child dependency at every other level of income out of the equation. The difference in ability to pay of the earner with and without dependents is largely ignored. At the same time, welfare supplementation of earned family incomes has been largely (and deliberately) confounded with welfare provision for the semi- or unemployed.

Part B

Data of the Achievement and Loss of Horizontal Equity

Comparisons of Family and Child-free Incomes: Methodology

We can now look fruitfully at detailed figures of the tax and welfare regime in the half century from 1950 to 1997 in order to substantiate the claims made in the previous section. We will begin in the period in which horizontal equity was achieved primarily via taxation, but on a foundation of wage differentials favouring the family. We will then pass through a transitional period from the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s, ending with the present period of strictly targeted welfare payments against a background of non-differential wages and taxation.

Projections for reform must address the impact of changes in the rules and regulations of fiscal policy and social security. Surveys of household income, such as those conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), are less appropriate for this purpose, for they can provide little insight into why particular changes in policy should lead to particular changes in outcome. Further, because they are samples and dependent on self-reporting, they pose problems of validity. Nor are they available for most of the period under consideration. Strategies devised by taxpayers to circumvent the effects of any set of regulations are also marginal to our concerns. It is important to consider what the rules project, as distinct from outcomes resulting from evasion of the rules—evasions which might not be sought if the rules were fairer.

The crux of the analysis that follows is a comparison of family and individual (that is, child-free) earners’ net incomes—that is, of disposable incomes after tax has been deducted and welfare payments have been added. To permit this comparison, calculations were performed on sample incomes at half-decade intervals employing the tax and welfare rules and provisions for the years from 1950 to 1997. Copies of the tax forms for PAYE earners for the period were obtained, and tax payable was calculated according to the instructions provided. Post-tax income for family earners was then amended by the addition of all direct subsidies and welfare payments available for a family of the chosen size at a number of given income levels, as garnered from a variety of reliable sources, historical and bureaucratic. Thus, a set of post-tax-plus-welfare (PTW) or disposable incomes was arrived at for further analysis and comparison.

Sample earnings

The first step in the process was to select appropriately representative pre-tax income levels in order to provide a picture of the comparative financial circumstances of a sufficient range and proportion of wage and salary earners. As our interest is primarily in the capacity of a husband working full-time to support a wife and family, adult male full-time Average Weekly Earnings in each of the target years was the obvious baseline figure, and this was converted in each instance into average annual earnings (AAE), since tax is calculated on gross annual income. This data is available from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, with earnings from the pre-metric years converted into dollars. All references to Average Weekly Earnings and wage and salary earners hereafter imply adult male full-time workers, unless otherwise stated.

The Basic Wage in 1950 and 1955 stood at 70% of Average Weekly Earnings. In 1960 it had fallen to 64%, and in 1965 to 58%. With this falling relationship likely to continue when the Basic Wage was replaced by minimum wages in 1967, it appeared appropriate to perform calculations on a pre-tax income set at 50% AWE for the years from 1965. The intermediate income of 75% AWE, which was not much above the Basic Wage in 1950, was calculated for the whole time period.

For the higher than average range, 200% and 300% AWE are frequently cited in wage studies. ABS Labour Statistics, however, show that so small a percentage of salaries have risen above the 200% AWE level since 1980, that incomes at this level are incidental to the general picture. In 1980, a man earning 300% AWE was in the top 1% of salary earners, and someone earning 200% AWE was in the top 5%. Thus 95% of wage and salary earners in Australia earned at 200% AWE or below in 1980. In 1990, again only 5% of salary earners were above 200% AWE, and in 1995 this had risen only slightly to 6%. For this reason, the upper limit of income chosen for tax and welfare calculations was 200% AWE. The most wealthy in this range earn perhaps four times the wage of the least wealthy. The 5% earning more are inconsiderable for general questions of family well-being within the taxation and welfare structure.

The numbers in the upper portion of the range are relatively few. Eighty-five percent of wage earners received 150% of AWE or less (putting only 10% between 150% and 200% AWE) in 1980, and this proportion rose to about 90% in 1990 and 1995, with only 5% of full-time adult males earning between 150% and 200% AWE. So the vast majority of Australian men earn within 50% of AWE on either side. Moving further down the scale, 75% earned 130% AWE or less in 1980, 117% or less in 1990, and 122% or less in 1995. Thus at least half of those earning above AWE today earn a mere 20% above it.

It therefore seemed appropriate to calculate taxation figures for earners on 120% AWE, as well as the intermediate figure of 150%, and to give earners at this level more prominence in the analysis than those on 150%, who represent a relatively small proportion of income earners. In 1990, approximately 30% of adult male full-time earners were at 75% AWE or below, with 5% at 50% AWE or below. The weekly and annual dollar earnings at each of these levels of Average Weekly Earnings across the half-century are shown in Table 1 of Appendix 2.

Earners with and without dependents

The concern of this analysis is with family income protection via taxation and welfare. The achievement of universal family income protection necessarily hinges on accommodation of family size, as the demands on an income increase with family size, and the portion available to each member decreases proportionally. It was therefore appropriate to base calculations on a family at the larger end of the spectrum, although one with sufficient incidence to be representative. Further, demands on family income increase with the ages of its children, and the impact of taxation and welfare provisions will vary in relation to the age of the child. As the high-cost stage of families is not avoidable, it is appropriate to base calculations on a family with older children of designated ages, as this represents a substantial proportion of the life-cycle of each family.

The average fertility rate of women in 1950 was three children. By 1990, this had dropped to two. But this under-represents the average family size, as not all women will have children. In 1993, 38% of families currently had one dependent child, 39% had two children, 17% had three children, and 6% had four or more children (Australian Bureau of Statistics Year Books; Sullivan et al. 1999). This makes a family of three dependent children an appropriate choice for analysis as it is at the larger end of the spectrum but nevertheless represents a substantial percentage of Australian families. Many of the 77% of one and two child families will go on to have more children. Thus, at any one point in time, over 20% of Australian families will have three or more dependent children.

In 1992, 43% of Australian households contained a couple and their dependent children and 9% a sole parent and dependent children. A further 43% contained a couple without dependent children, and 5% consisted of only single adults (Australian Bureau of Statistics Year Books). Child-free earners fall into three basic types: (a) younger people in the pre-family stage; (b) older people in the post-family stage; and (c) people across the age range who never have children. In all categories, many will be members of couples whose partners are also working full-time, each of whom is taxed as an individual but treated as part of a couple for welfare purposes. The number of child-free earners is probably at least as large as the number of family earners with three children. Sole parent families are not the subject of comparisons in this analysis.

Single-income family

The family earner group needs further definition. Our concern is with the ability of a family earner to support both wife and family, thus permitting full-time care of children by the mother when the age, number, or special requirements of children make this the parents’ best option in promoting their well-being. Thus, our family will be presumed to contain only one full-time adult earner.

It is, of course, increasingly common for both members of a couple with children to work, although one of these incomes, the wife’s, is more likely than not to be part-time. In 1997, average male full-time earnings were $36,000 p.a. and average family earnings were $42,000 p.a., indicating on average a fairly small contribution by employed mothers and/or a preponderance of family earners in the upper half of the middle group of wage brackets (WAA Newsletter 1998). That many mothers of two or three children work does not necessarily indicate that they do so out of choice, and it is not necessarily desirable that they should be forced to do so. The Australian Council of Social Services (ACOSS) Commission for the Future of Work (1997) was of the opinion that the family should not need to rely on a second income, nor on children’s earnings (many school children are now working), to survive financially or to maintain a reasonable standard of living.

In a family with three children, the mother’s part-time job often needs to be discontinued because of unforeseen family needs. This is so even with the family of older children, who continue to need supervision after school and whose emotional demands on the family are in many ways greater than when they were younger. Thus, it is appropriate to assume for the purposes of this study’s calculations that wives and children are not earning.

Nevertheless, given the smallish size of most families today, the retention of dependent offspring into what is virtually adult life, and the availability of part-time work, most mothers today will wish to engage in some paid work outside the home, at least once their youngest children are well settled into school. It is therefore reasonable, when we eventually come to assess the requisite levels of family income protection, to build into our calculations the expectation that mothers in two-parent families of moderate size will, shortly after their youngest child reaches school age, be able to contribute at least some few thousand dollars a year to family income.

Age of dependent children

In the early 1950s, Child Endowment was paid for dependent children to the age of 16. By this age, most children had left school and were in employment. As more extended education became increasingly common, tax deductions for dependent students were introduced, thereby reducing taxable income. The cut-off age rose to 22 in the 1960s, and to 25 for the Austudy welfare payments of the 1980s.

For the purposes of these calculations we have assumed that the three children of our target family are aged under 17 for the first two decades of the series, and thereafter that they are aged 12, 15 and 18. This takes into account the higher costs of older children, a fact recognised in taxation provisions in the 1960s and partially in targeted welfare payments in the 1990s.

Childcare payments and the special pre-school child payments of recent years do not therefore feature in the calculations. This is in part deliberate. Over the last two decades childcare subsidies have represented a form of family welfare. But as eligibility is predicated on the mother working, and substantial hours are necessary for significant benefit to accrue, it represents the channelling of revenue into the creation of a forced choice in family lifestyle. It therefore functions quite independently of mainstream tax and welfare provisions for horizontal equity. The comparative welfare of the two-income and the single-income family with pre-school children, which has been the subject of many invidious comparisons, is not the focus of attention here, but rather the treatment of the family as compared with the child-free earner.

Tax and welfare benefits

Appendix 1 lists the various deductions, rebates, subsidies, levies and family payments which have modified the raw tax rates at each half decade from 1950. As detailed in the previous chapter, from the mid-1980s a plethora of family payments began to impinge on a sub-set of earned family incomes, those below Average Weekly Earnings. These payments were successively modified and became indistinguishable from the child component of Unemployment and Sole Parent Benefits.

The major Family Payments introduced in the 1980s have been included in the calculations, but indirect and special benefits, routinely available to families on Unemployment Benefit and on 50% and 75% AWE, but not to families on Average Weekly Earnings and above, are not taken account of. Examples are phone allowances, rebates for water and council rates, and free car registration. Those who obtain a Health Care Card are eligible for free ambulance, free glasses, cheap medicine, rebates or waivers on electricity, half-fares on train, bus and ferry, and waiver of bond and first week’s rent for rental accommodation. These benefits could amount to $3,000 or more a year for a family with three children. There is also Rent Assistance for low-income families and this has been calculated for families on 50% AWE (and on Unemployment Benefit), but not for families on 75% AWE and above, who may aspire to home ownership and be paying off a mortgage for which no assistance is available.

These special benefits can put lower-income earners financially well ahead of those with higher initial incomes when, as we shall see, the major Family Payments themselves result in the virtual elimination of differences in disposable (post-tax+welfare) income across a range of earnings.

These then are our comparison groups—the family earner with a wife and three children, and both the single and partnered child-free earner (without dependents). The child-free earner comparison group presumes an earned full-time income at the disposal of that person. Our concern, for the purposes of analysis, is with the financial position of the family members dependent on one full-time salary, compared with that of the earner without dependents on the same full-time salary.

Family versus child-free incomes: A comparison of income trends 1950–1997

Loss of universal family protection

The following analysis of the family’s fate from 1950 to 1997 consists in the detailed examination of numerical data at five to ten year intervals across that period of nearly 50 years. Earnings at the various percentages of Average Weekly Earnings chosen for analysis were identified across the time period. Using these figures as a baseline, tax payable and welfare payments received at each of the selected levels of Average Weekly Earnings at each five year interval were calculated for both family and child-free earners and net tax payable obtained. Finally, the disposable or post-tax+welfare (PTW) income remaining to the family and the child-free earner at each level of earnings was calculated. These figures are reported in Appendix 2.

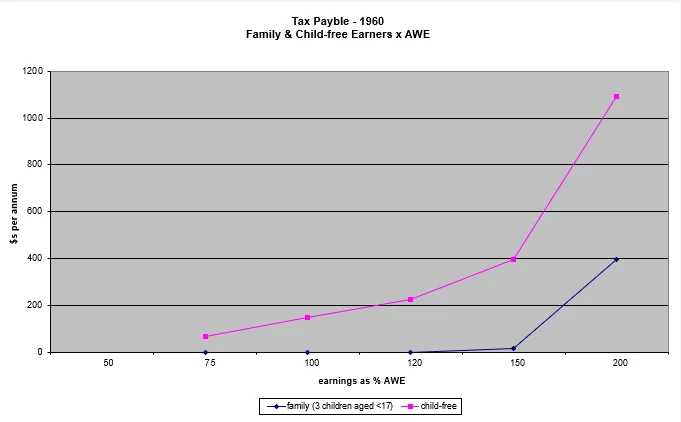

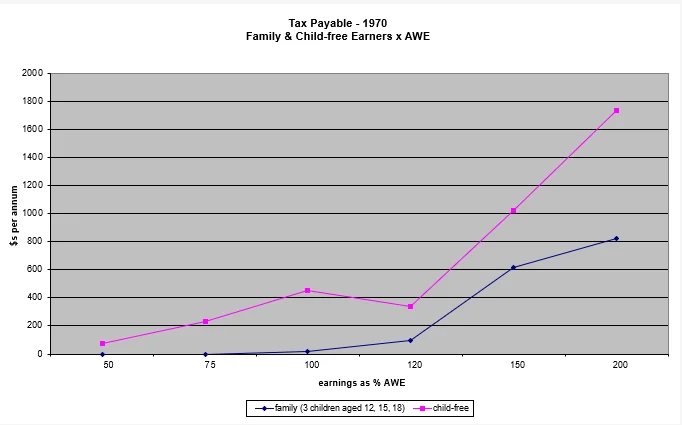

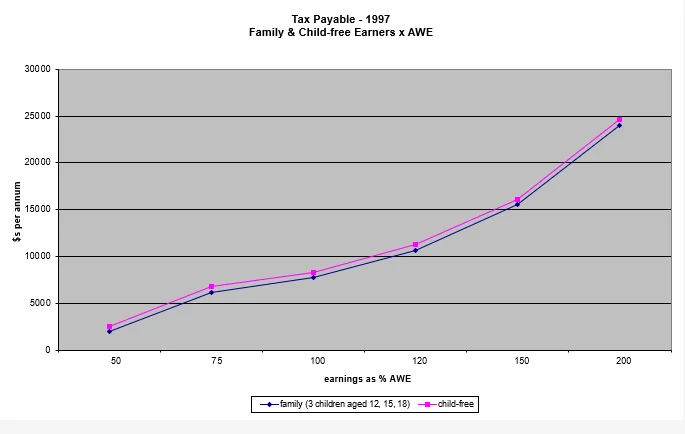

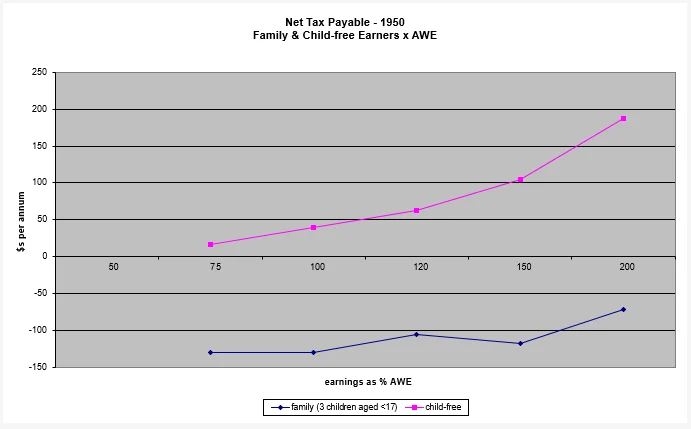

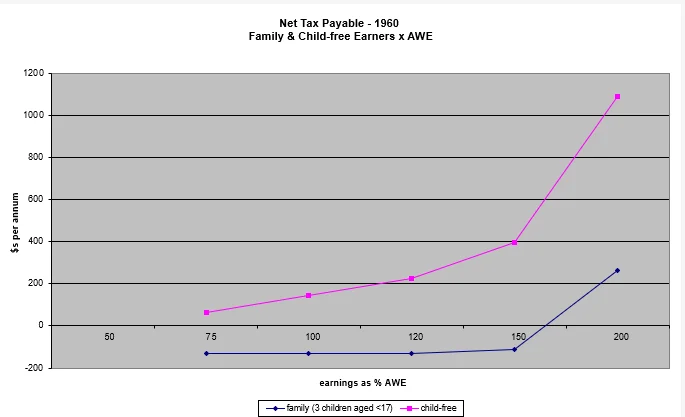

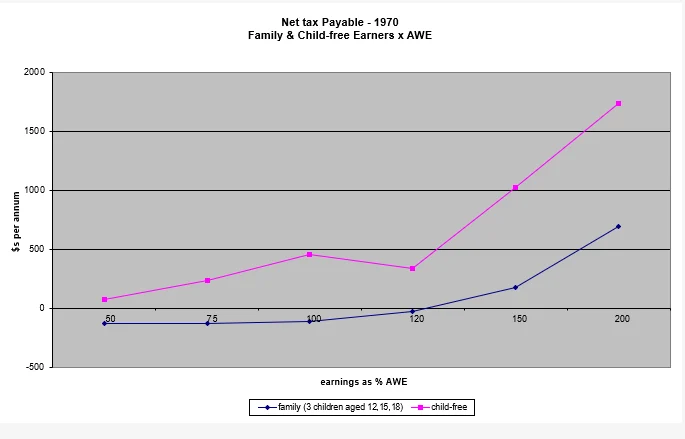

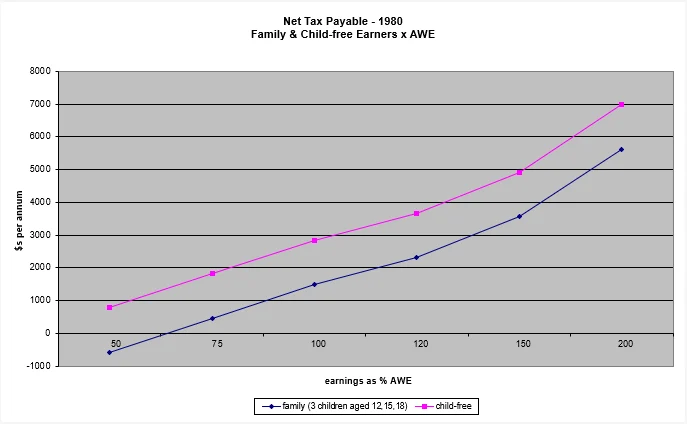

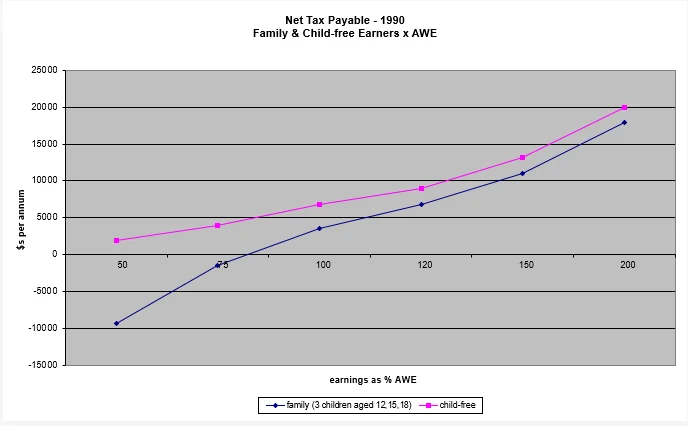

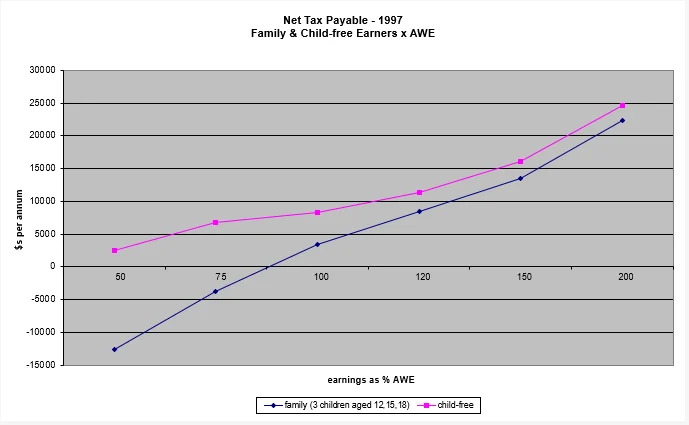

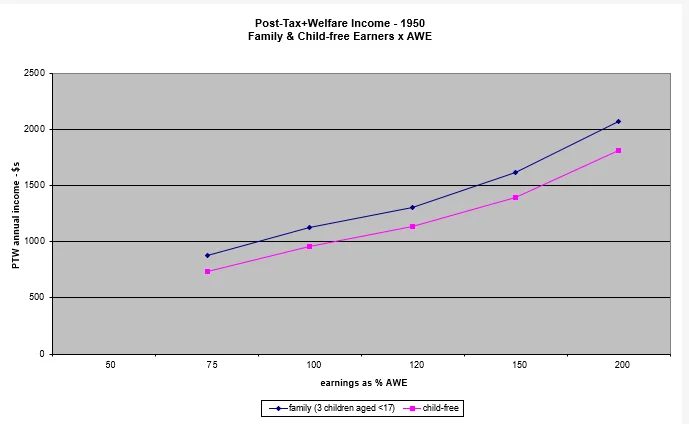

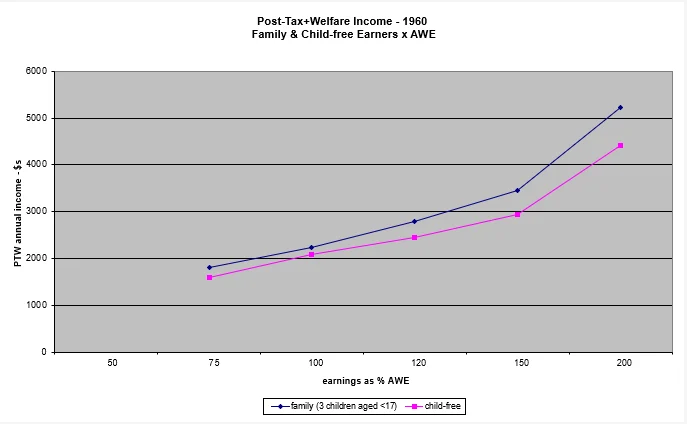

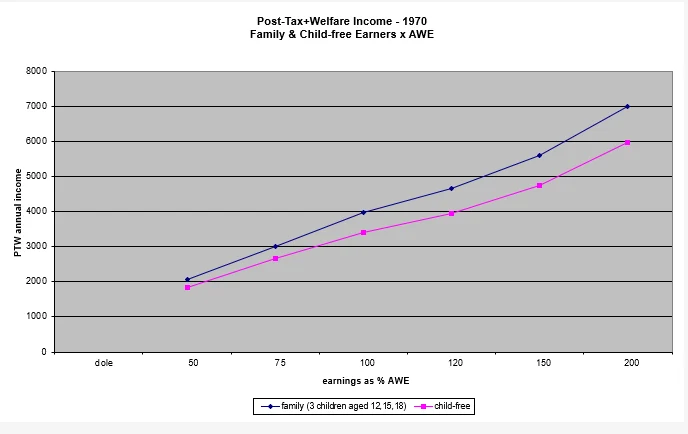

The trend revealed by the figures is more easily appreciated if the data are presented in graphical form. Figure 1 shows tax payable (ignoring welfare) by child-free and family earners at decade intervals from 1950, ending in 1997. It can be seen that from 1950 to 1970, families with three children and an income up to the level of Average Weekly Earnings paid no tax. In 1960, when the full array of family tax deductions was in force, virtual freedom from taxation for the average family extended up to 150% AWE. At all levels of earnings, child-free earners paid more tax than family earners. Although there was increasing disparity between tax paid by child-free and family earners as income rose, taxation was nevertheless remarkably progressive for family earners in the higher reaches of income.

Figure 1

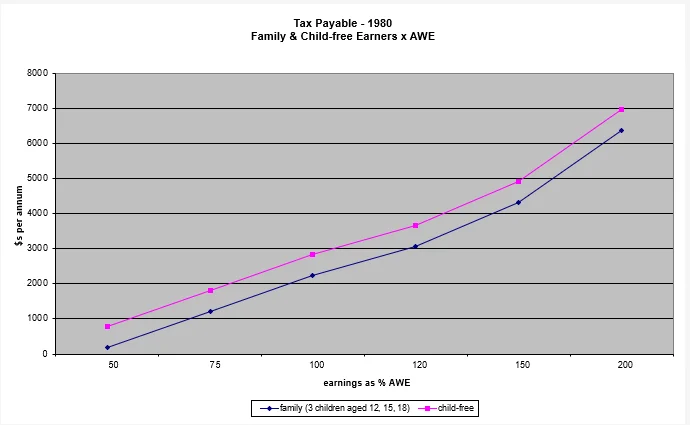

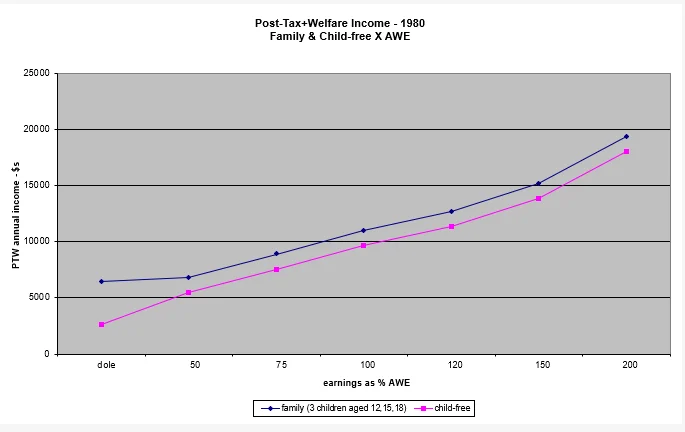

By 1980, however, the exemption of low to middle income families from taxation had disappeared, as a result of the increase in taxation at low levels of earnings and the abolition of child-related deductions and their substitution by the Family Allowance. This was at great cost to the child-free versus family tax differential. The tax benefit provided for families was now diminished to the flat rate of the Dependent Spouse Rebate (DSR), which replaced the previous deduction for dependent spouse. Low as well as higher family incomes were less protected than under the previous deductions system. Further, with each succeeding half-decade, as inflation raised the cost of living, the real value of the non-indexed Dependent Spouse Rebate decreased. The tax differential for family versus individual earners was vestigial in real terms by 1997, despite the introduction in that year of the ‘family tax initiative’, a small raising of the tax threshold on a per child basis. It can also be seen that taxation now no longer rose more sharply at higher income levels than at low.

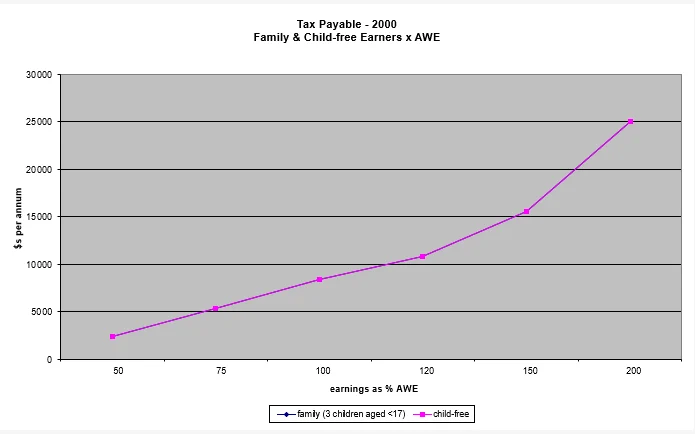

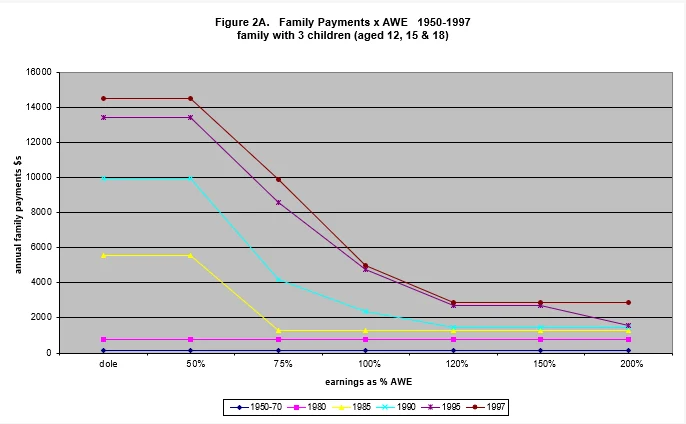

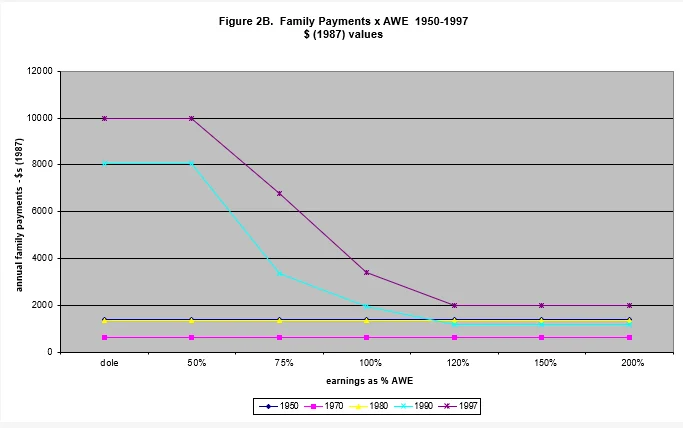

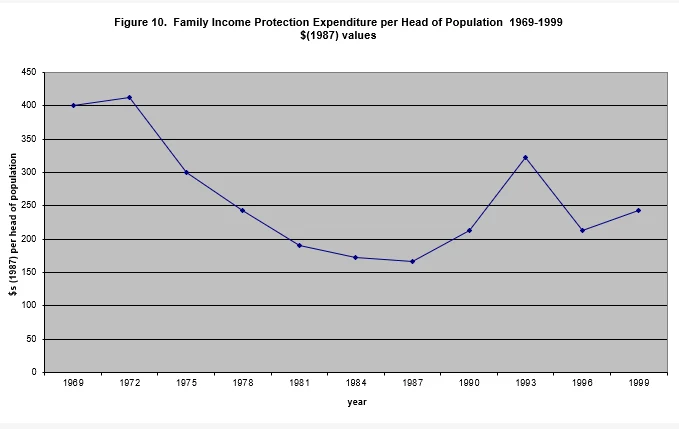

Figure 2 demonstrates changes in the pattern of Family Payments at the various levels of income across the half century (in actual dollars disbursed). As can be seen, payments to families—Child Endowment and then Family Allowances—from 1950 to 1980 were flat across the range of incomes. They were a universal measure, designed to promote horizontal equity between family and child-free incomes. They did not, as later, promote vertical equity between higher and lower family incomes. By contrast, in the 1980s and 1990s, there were increasingly larger Family Payments at the lower levels of income, diminishing rapidly as earnings rose above Average Weekly Earnings to an actual value little different from that of Child Endowment from 1950 to 1970, when wage differentials and tax deductions were the major instruments of family income protection. Between 1985 and 1990, Family Payments became primarily a welfare payment to low-income families. Family income protection across the full range of incomes was no longer a goal.

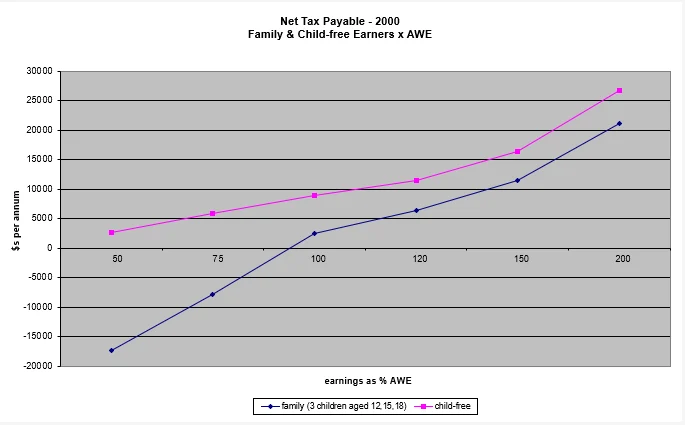

Net tax payable by family and individual earners (that is, when welfare benefits are subtracted from tax paid) from 1950 to 1997 is shown in Figure 3. In 1950, the combined effect of tax thresholds, graduated tax rates, deductions and Child Endowment was a rise rather than a loss of income even for family earners on 200% AWE paid no net tax, and this remained so up to 150% AWE in 1960 and 120% AWE in 1970. The slow rise in taxation of incomes of both types from 50% to 120% AWE was substantially flattened for family earners so that for them it was as if taxation only began well beyond AWE.

Figure 3

Thus universal tax deductions and Family Payments combined to provide income protection for the family. As we have seen, tax deductions played the major role in this outcome rather than direct Family Payments. Most wages were close to sufficient for most families’ needs, provided they paid little tax.

True to later criticisms, the disparity in net tax paid between child-free and family earners increased with rising income, although there was a sharp rise in net taxation for both child-free and family earners beyond 150% AWE. By contrast, in 1980, with tax deductions removed and a single universal Family Payment, the differential was uniform across income levels. This also meant that, proportional to income, at higher income levels family income protection was much reduced. Family earners had lost relative to child-free earners, and child-free earners at higher income levels had gained most.

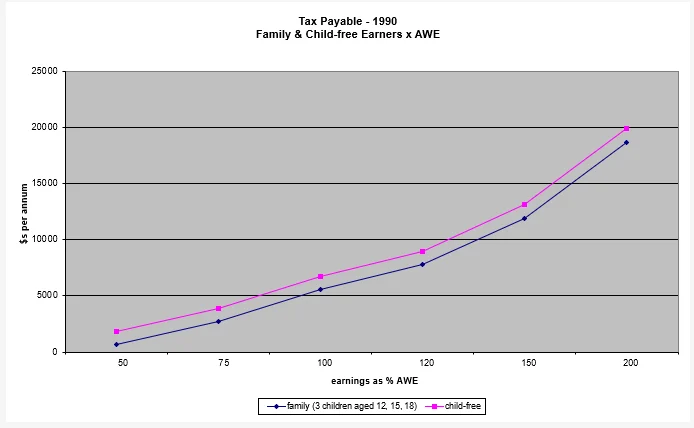

In the 1990s, a new effect appeared. Families below Average Weekly Earnings now received substantial additional income in Family Payments, so that tax-free incomes for families reappeared at incomes below Average Weekly Earnings. Substantial family income protection existed in the 1990s, but only by virtue of large welfare-style payments and only at the lowest income levels. Very large benefits were granted at 50% AWE, amounting almost to total tax paid at higher income levels. But as this low level of earnings was rare in fully employed workers (5% in 1990), and even more rare in mature earners with growing families, this recognition of the realities of family expenditure was limited to only a minority of Australia’s families. The majority of families in 1990 and 1997 were, technically, required to pay net tax at levels not very different from their child-free earner counterparts. They received little in Family Payments in recognition of their higher costs. The net tax figures demonstrate that family income protection as a universal measure in the 1990s had practically disappeared.

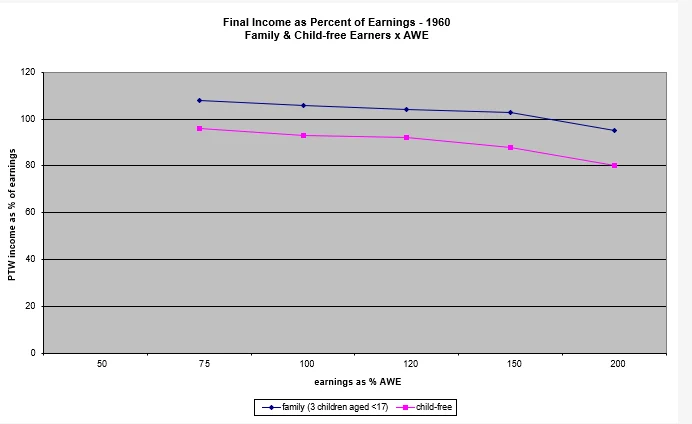

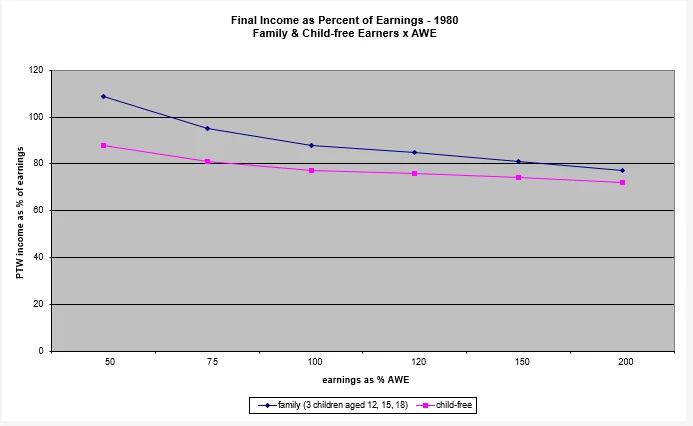

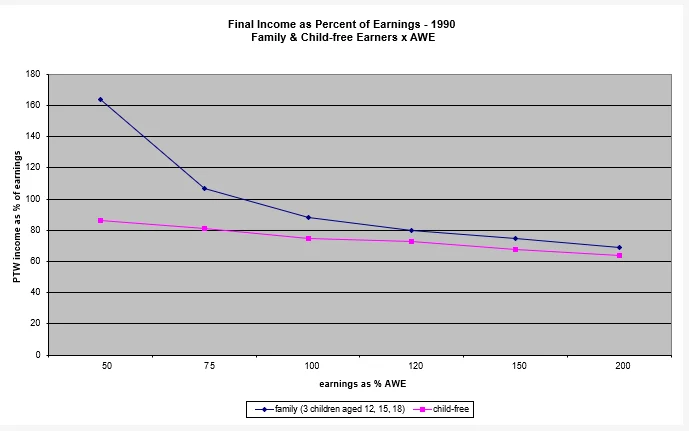

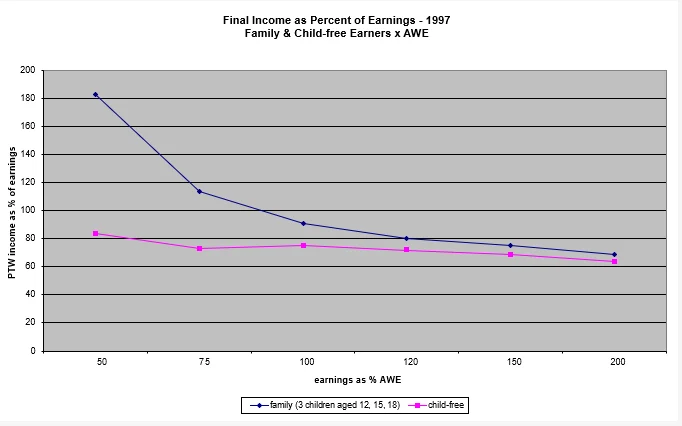

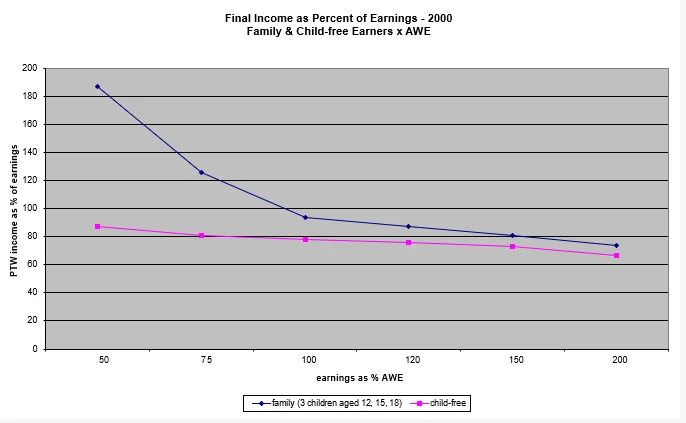

The loss of universal income protection for families is graphically demonstrated in Figure 4 which shows post-tax+welfare (PTW) incomes as a percentage of initial earnings in 1960 and at decade intervals from 1980. In 1960, the comparatively higher percentage of income retained by family, compared with child-free, earners was stable across the range of initial earnings, at about 15%. Thus percentagewise, higher income families were not advantaged over lower income families by the use of deductions. In 1980 when the flat rate Family Allowance had been substituted for deductions, family income protection was reduced at the higher levels of income compared with the lower, ranging from 20% to a mere 5% higher comparatively at double AWE. In 1980, Family Payments had boosted the after-tax income of the family on 50% AWE to 109% of initial earnings, but in 1990 the increase was to 164%, and in 1997 to 183% of actual earnings. As a result, in 1997 the difference in percentage of income retained between family and child-free earners at 50% AWE was 99% (183% compared with 84%), but it was only 16% at Average Weekly Earnings, a mere 8% at 120% AWE, and 5% at 200% AWE. Thus family income protection vis à vis earners without dependents became insignificant above AWE.

Figure 4

The elimination of family income protection in taxation made large welfare payments to low-income families essential as an anti-poverty measure. But as these graphs show, its meaning for moderate family incomes was ignored. An income of 120%, 150% or 200% AWE does not represent the same wealth or high income for a family as it does for an earner without dependents, but family income protection via either tax or welfare provisions was largely abandoned for this group.

The ACOSS Tax Reform Pack (1997) declared that, ‘The progressive income tax system is the keystone of Australia’s tax system. It is designed to take a greater proportion of income from taxpayers with a greater ability to pay.’ The sets of graphs in Figures 1 and 3 demonstrate that despite the formality of graduated tax rates, the present tax system is only halfway progressive in that it ignores the reduced ability to pay of the earner with dependents, compared with the earner without. It no longer incorporates the principle of horizontal equity.

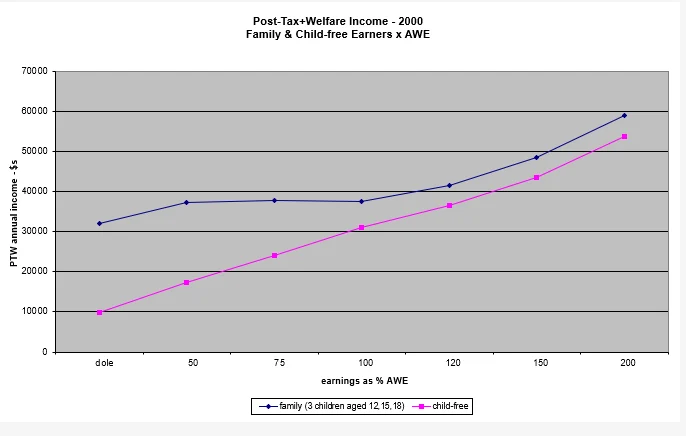

Equalising income

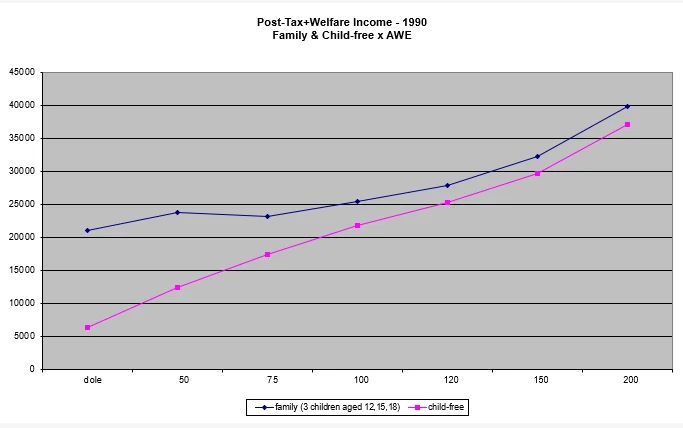

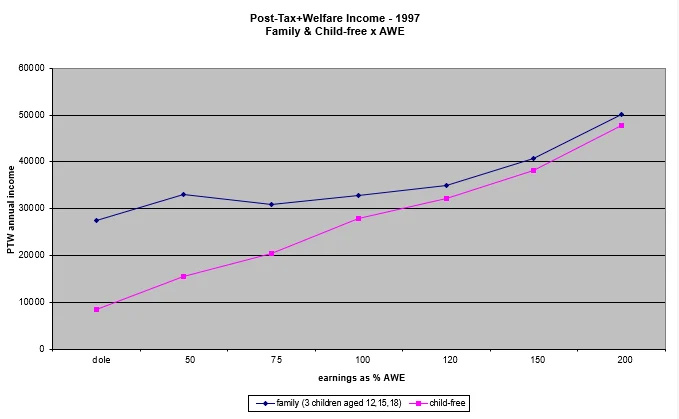

The mirror image of these developments in tax and welfare policy is seen in PTW income itself. Figure 5 shows PTW income for a family with three children and for child-free earners at decade intervals from 1950, ending in 1997.

In assessing the trends revealed, it should be borne in mind that they occurred against a background of diminishing adequacy of minimum and average post-tax income for family expenditure needs, due to the abandonment of the Basic Wage system and to the increase in the percentage of income taken by taxation. Thus a small gap between disposable income at male adult Average Weekly Earnings for a family and a child-free earner in 1950, at a time when the Basic Wage came close to the needs of a family of five and when the majority of child-free earners were in fact on a wage lower than that for adult males, does not indicate the same degree of inadequacy of average family disposable income that a similar proportional gap represents in 1995, when minimum earnings after taxation no longer attempted to represent a ‘family wage’.

Throughout the period from 1950 to 1997, it can be seen (Figure 5) that the PTW incomes of child-free earners, despite progressive taxation, show a substantial rise across the range of initial earnings, although one that is flatter than the rise in actual earnings. That is, the tax/welfare system did not impose equality of final incomes for child-free earners across any points in the range.

Figure 5

From 1950 to 1980 for family earners too, a fairly steady rise in PTW income is seen as earned income rises, and again the workings of progressive taxation can be observed in that the rise in family PTW income is flatter than that in actual earnings. Thus, until 1980, family and child-free earners fared similarly as regards vertical equity. But in 1990, in contrast to the situation for child-free earners, for family earners the rising gradient in PTW income shows signs of elimination for those below Average Weekly Earnings. And in 1997 it has technically disappeared across the income range from 50% to 120% AWE—that is, to the 75th percentile of full-time male earnings. (The dip in PTW income at 75% AWE appears because Rent Assistance is not incorporated in the calculation of Family Payments for this income level. If it were, the drop would flatten. The family on Average Weekly Earnings is not eligible for Rent Assistance.) The rising gradient reasserts itself only for the minority of family incomes above 120% AWE.

In taxation parlance, in 1997 Effective Marginal Tax Rates (EMTRs) across the range of family incomes to 120% AWE were close to or at 100%. This is no chance occurrence but the outcome of a carefully constructed integration of tapered welfare payments and tax rates. Referring to Table 5 in Appendix 2 for the actual figures, one can see that our family earner in 1997, whether earning $18,000, $27,000, or $36,000, had a post-tax income in the low $30,000s. If one takes into account the numerous indirect benefits available to very low income families but not included in the present calculations, and that the extra cost of employment is estimated at about $2,000 p.a., even the family with three children on the dole and receiving Unemployment Benefits plus maximum Family Payments nominally amounting to $27,000 was in much the same financial situation as employed families earning up to AWE, and families on 120% AWE or $43,000 p.a. were not much better off.

By contrast, even at 50% AWE, a child-free earner’s PTW income is well above the level of the single dole, and child-free earners maintain their relative positions in the income range as earnings rise. Higher-income family earners, too, are allowed some measure of increase. But it is not until a family with three children reaches the comparatively rare salary levels of 150% and 200% AWE that it can, technically, begin to lift its financial situation much above the level of families on unemployment benefit.

Thus, although a gradient in PTW income is permitted to all child-free earners and to higher income families, this is not the case for family earners across the lower to middle-income range.3 Families cluster in the middle income ranges in terms of earnings and so this levelling takes in a high proportion of families. Australian Bureau of Statistics figures for 1990 showed 55% of adult male full-time earners at between 75% and 150% AWE (Australian Bureau of Statistics Labour Statistics). At mid-decade, only one of the ten deciles of primary family earners accounted for wages above $50,000 p.a. (Apps 1995). Five lay between $30,000 and $50,000, three between $20,000 and $30,000, and incomes of less than $20,000 accounted for only one decile.

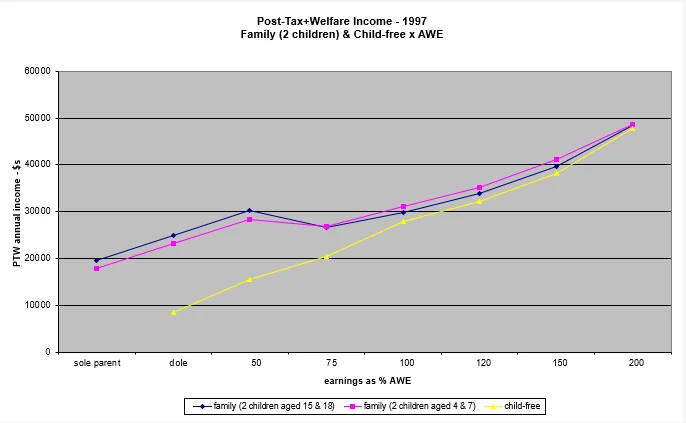

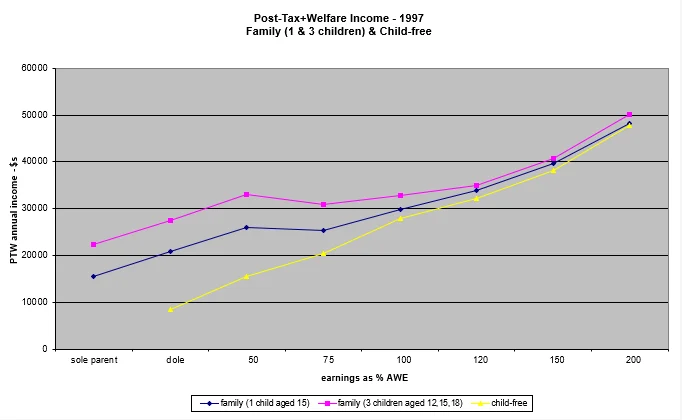

These effects are not, of course, confined to our sample family with three older children. Figure 6 shows PTW incomes for families with two young children (including pre-school), with two teenagers, and with one teenage child. Effective Marginal Tax Rates of 100% again appear between 50% AWE and Average Weekly Earnings. The family with two children—and therefore with lesser expenses than the family with three—can escape this compression at a slightly lower level of earnings, that is at Average Weekly Earnings rather than 120% Average Weekly Earnings. The family with one child can do so at between 75% AWE and Average Weekly Earnings. Thus all families are affected by the system, but the family with larger expenses is affected most.

Figure 6

The only government assistance that a middle-income family can access to escape this compression to welfare levels of income is childcare assistance, and this implies a mother in the workforce. Nevertheless, the average two-income family with the mother working part-time is caught in the same trap. The mother’s earnings are included in family income for purposes of assessing welfare eligibility, and so at the lower ranges of income the advantage of the mother’s earnings is largely lost due to the withdrawal of Family Payments. Only when the threshold of 120% AWE, about $43,000 in 1997, in combined earnings of husband and wife is passed can the family substantially improve its PTW income.

Thus the mother of pre-school children whose husband is on Average Weekly Earnings must work substantial hours if her access to childcare is to raise family income significantly. Our family of older children is not, of course, eligible for such aid, but the recourse of the mother working will have the same limited effects. Only if the husband in our family example is already earning around $43,000, or 120% AWE, can the wife’s earnings initially improve their disposable income. This explains the otherwise odd finding that lower-income primary earner families are least likely to supplement their incomes with a secondary (mother’s) income (Apps 1995). Work participation of a secondary earner is greatest at the middle-income levels where it begins to be advantageous. It falls after the primary earner’s income passes $50,000—that is, when it approaches the top decile of primary family earnings, suggesting that the higher rates of work participation at middle income levels are forced upon families by financial need rather than choice.

Like the changes to the tax system which removed family income protection, the acceptability of this outcome—that is, the engineering of equality of disposable income across the lower range of family earnings—was never publicly debated. Even if it were democratically approved, it hardly seems just to impose it on one section of the populace only. If we are committed to using taxation and welfare to equalise incomes, then surely this should be applied to all citizens, not just to families.

Overview

Whatever the intentions of policy development, current tax and welfare regulations since the late 1980s have meant that the majority of families with one parent full-time in the workforce will live at very little, if at all, above the level provided by welfare for the unemployed family. Families with very low earnings (probably the result of less than full-time employment) have their incomes raised to this level by Family Payments, while for moderately earning families taxation reduces income to below this welfare minimum and tapered Family Payments bring it back to the welfare level, but not above it. If Unemployment Benefit incomes are considered to be geared to poverty-line necessity, then the current workings of taxation and welfare could be construed as designed as far as possible to keep families, regardless of earnings, on the poverty-line.

In 1997, the ratios of PTW incomes of families earning Average Weekly Earnings and 120% AWE to the income of a family entirely on welfare benefits were a mere 1:1.2 and 1:1.3, respectively (Appendix 2, Table 7). These ratios diminish to 1:1.1 and 1:1.2 if the cost of earning a living is built into the calculation, so the difference is inconsiderable, perhaps even non-existent if the welfare family’s indirect benefits are accounted for. By contrast, the ratios of PTW incomes of child-free earners on Average Weekly Earnings and 120% AWE to the single Unemployment Benefit were 1:3.3 and 1:3.8, respectively—workers without dependents were more than three times times better off than those who were unemployed. Even the family earner on 200% AWE retained less than twice the family Unemployment Benefit, while child-free earners on 200% AWE had disposable incomes six times those of single persons on Unemployment Benefits.4

The essence of my criticism and analysis is not that it is wrong to bring the poorest semi- or unemployed families up to current welfare levels, on which many employed families live frugally but decently. It is against natural justice, however, to bring middle-income families with a range of earnings above this level uniformly down to this lowest common income level. The development of this problematic situation is largely due to the failure to maintain tax differentials as between family and child-free earners. Although both pay a higher proportion of their incomes in tax than they did two decades ago, family earner taxation has increased six-fold while child-free earner taxation has merely doubled.

A major effect of the move from universal tax exemptions to targeted welfare in the last decade and a half is, then, that we have a privileged child-free earner population relative to families. In contrast to previous decades, at higher wage levels they pay tax similar to that of family earners, who receive little in benefits. At all wage levels their post-tax income relative to the single dole is many times greater than an equivalent family comparison. Child-free earners are contributing a far lesser proportion of tax revenue compared with family earners than they did three decades ago.

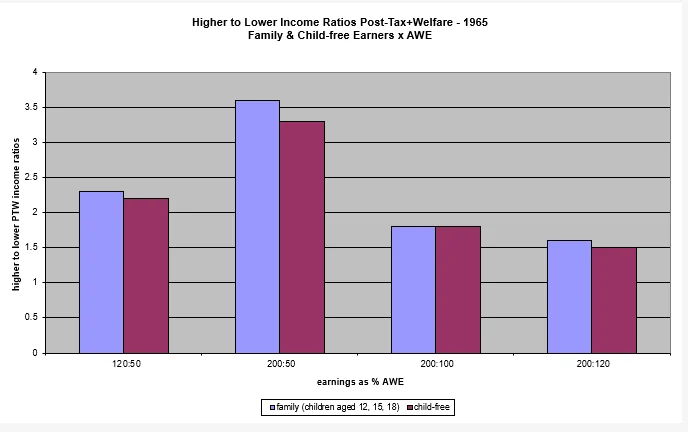

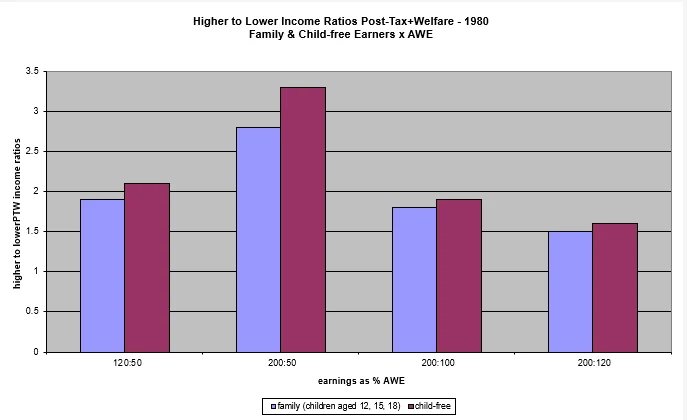

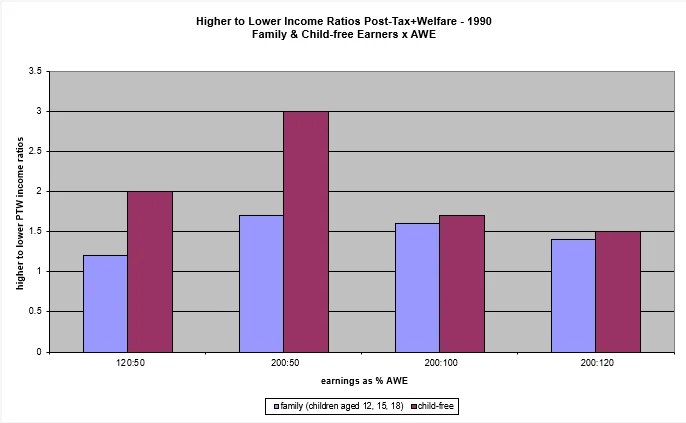

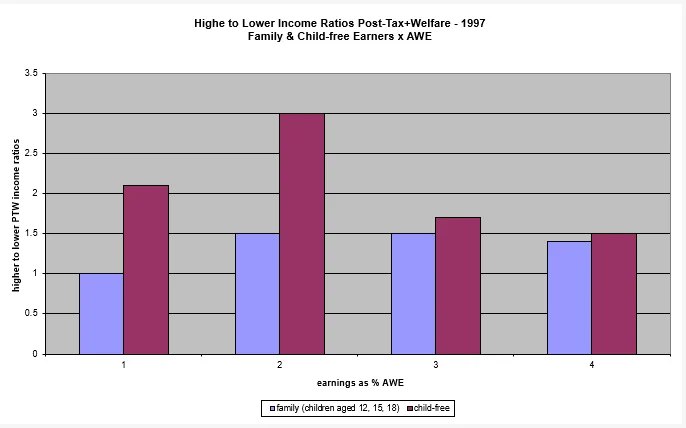

The high EMTRs across the lower family income range are occasionally deplored for their disincentive effect on work effort. Semi- or unemployed parents gain little or nothing (except respect) by taking up low or average paying jobs, and lower-income employed parents may be tempted into semi- or unemployment. An employed father of three children told The Sydney Morning Herald (Horin 1996) that his family could barely live on his salary of $29,000 a year. ‘If my wages dropped lower,’ he said, ‘I would consider going on the dole.’ Our figures show that this was indeed a sensible assessment of comparative financial advantage.