Executive Summary

Australia’s tobacco control policy has reached a breaking point. For decades, bans on advertising and steady excise increases reduced the incidence of smoking and raised reliable revenue. In 2013, the Commonwealth accelerated the tax escalator, legislating four annual 12.5% increases and later adding further excise increases. On its own terms, this approach appeared to work for many years; smoking prevalence fell steadily, and the policy was internationally lauded as a public-health success. Since 2019–20, however, revenue has persistently fallen short of Budget forecasts, and a violent illicit market has expanded.

The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) estimates that about $2.7 billion of excise went uncollected in 2022–23, with roughly $0.4 billion coming from domestic diversion and unlicensed production. Successive governments framed the accelerated excise schedule as a public-health intervention to make tobacco less affordable, reduce uptake, and drive daily smoking to very low levels. The current National Tobacco Strategy targets less than 10% daily smoking by 2025 and 5% or less by 2030. This raises a straightforward policy question: have sharp excise increases reduced smoking as intended, or have they primarily shifted consumption into illicit tobacco and other nicotine products, with the effective market price for many smokers falling as illegal supply has become institutionalised?

This paper explains how split responsibilities and misaligned incentives have produced this outcome. Drawing on the Ramsey–Pigouvian framework, it shows that excise has moved beyond the point where it is either efficient or corrective. Using public choice theory and the Djankov–Shleifer institutional model, it argues that the Commonwealth is rewarded for over-taxing while states and local communities bear the health, policing, and insurance costs of the disorder that results.

A counterfactual analysis combining Treasury forecast errors and ATO tax-gap estimates suggests that forgone revenue is measured in billions of dollars each year. These are conservative estimates because they exclude the costs of enforcement, arson, lost trade, and the erosion of respect for law.

The paper concludes that Australia needs policy clarity and institutional reform. Tobacco control cannot be both a public health programme and a revenue measure. Excise should be stabilised within an economically defensible range, inland enforcement strengthened, and the Commonwealth made fully responsible for the costs created by the tax it sets.

Introduction

Australia’s tobacco control policy has lost its way. Excise has kept rising, while legal sales have shrunk, and a large illicit market has emerged. Excise revenue once treated as a reliable cash stream has collapsed and now falls well short of Budget forecasts. Violent crime tied to illicit tobacco is now constantly in the headlines. This is not the result of bad luck. It is the predictable consequence of fragmented governance and responsibility where the Commonwealth sets the tax rate and pockets the money, states carry the health and policing bills, and local communities pay for arson, insurance shocks, and lost trade.

This paper argues that tobacco control policy suffers from government coordination failure. Responsibilities are split and incentives are misaligned. The Commonwealth has every reason to keep raising excise rates and to talk tough on smoking. States must deal with the public health costs and enforcement costs of tobacco control, but they have no claim on excise revenue. Retailers and households bear the social costs of criminality. When the level of government that raises the money does not pay the enforcement and social costs, the price lever will be over-used and the seams in enforcement will stay open.

Public statements have consistently presented the excise escalator as a health measure designed to encourage quitting, particularly among the young, rather than simply as a revenue device. Current ministerial releases continue to state that changes to excise are intended to help smokers quit and to protect population health; the National Tobacco Strategy treats affordability as the most effective lever for reducing smoking. These statements make clear what success would look like; sustained reductions in smoking prevalence, particularly among groups most responsive to price.

Two broad principles guide the analysis. First, excise has two legitimate economic roles. Ramsey taxation raises revenue from goods with inelastic demand. Pigouvian taxation prices the genuine external costs of smoking. Excise beyond those limits is no longer corrective; it becomes coercive. Second, policy must decide whether tobacco control is a public health programme or a revenue instrument. If it is about health, states should have the lead, and the Commonwealth should support enforcement and harm reduction. If it is about revenue, the Commonwealth should accept full responsibility for the costs its policy creates.

The paper sets out the evidence for this argument. It begins with a concise history of recent tobacco control in Australia and the economic logic of the Ramsey–Pigouvian trade-off. It then uses public choice theory and the disorder–coercion framework to explain why excise kept rising even as its effectiveness waned. A counterfactual analysis quantifies the fiscal cost of policy drift, and the paper concludes with practical reforms to restore coherence to tobacco policy.

Brief History of Australian Tobacco Control

Australia’s tobacco policy tightened steadily from the late 1970s. The first decisive step was the ban on television and radio advertising in 1976, followed by bans on print and sponsorship through the 1980s and early 1990s.[1] By the mid-1990s tobacco advertising had disappeared from mainstream media and sporting events.[2]

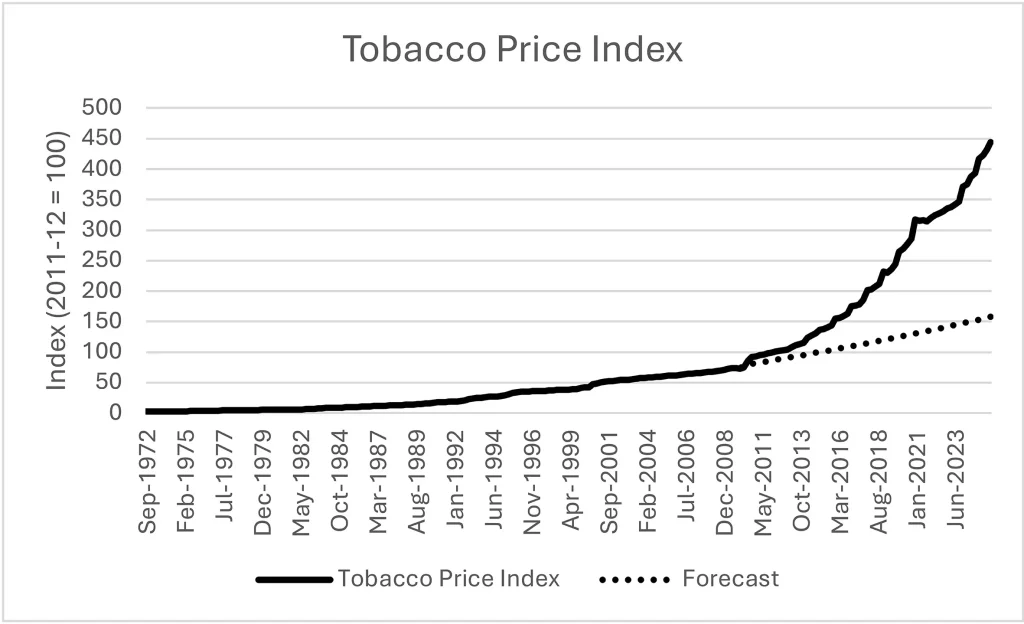

Price policy has since become the main instrument of tobacco control. After decades of steady — but slow — price increases, the price of tobacco (as measured by the Australian Bureau of Statistics) escalated very rapidly after 2010. Figure 1 below shows the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for tobacco products over the period 1972–2025. As can be seen, the CPI increased steadily until 2010 — after which it rapidly escalated. The dashed line in figure 1 shows a forecast time trend if the Tobacco CPI had remained on its pre-2010 trend. The divergence between the historical trend and the actual Tobacco CPI is very marked.

Figure 1: Tobacco Consumer Price Index 1972 – 2025

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics and author estimates

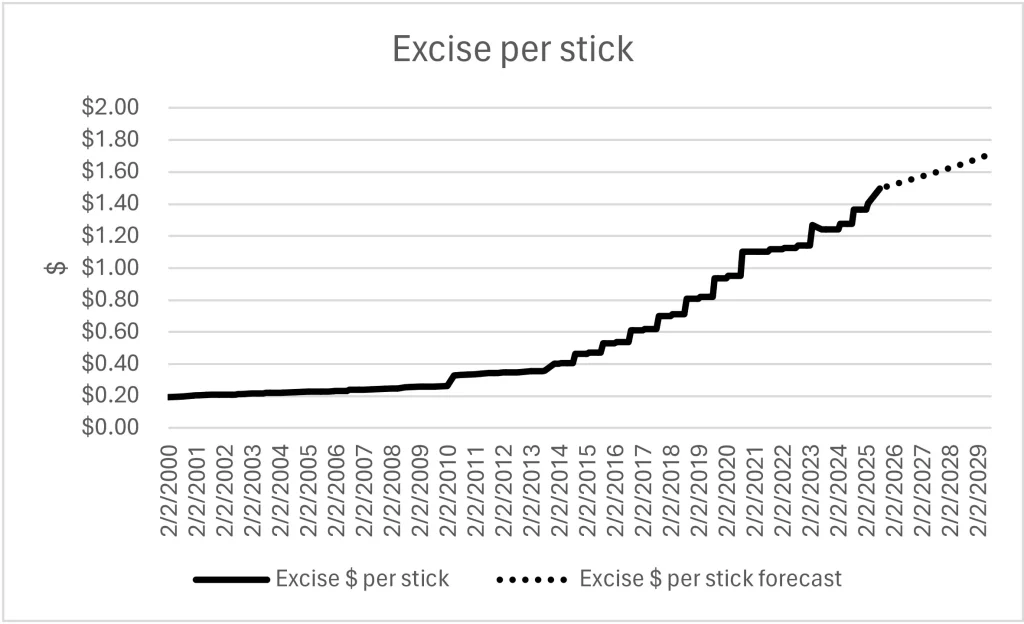

From the early 1980s, the Commonwealth had introduced regular indexation of tobacco excise to maintain real value, although discretionary rate rises remained occasional through the 1980s and 1990s.[3] This produced strong revenue growth and gradually reduced smoking prevalence. By the mid-2000s, excise was firmly established as the lead tool for discouraging tobacco use and raising revenue.[4] Figure 2 shows the growth of tobacco excise rates ($ per stick) since 2000.

Figure 2: Tobacco Excise ($ per stick) 2000 – 2025

Source: Australian Taxation Office[5]; Budget papers, Author forecast

In 2006, Australia mandated the addition of graphic warning labels to tobacco products. The next big shift was plain packaging. In 2012 the Tobacco Plain Packaging Act came into force, banning brand logos and standardising pack design. The measure aimed to make smoking less appealing, particularly to young people. While the government claimed that the policy was a success, the evidence suggested otherwise.[6]

Excise policy then took centre stage. From 1 December 2013, the Commonwealth legislated four annual 12.5% increases in tobacco excise, in addition to automatic indexation. After 2014, tobacco indexation was at average weekly earnings, not CPI. This escalator was later extended, and the May 2023 Budget announced a further 5% annual increase for three years from September 2023.[7] These were some of the steepest tobacco tax increases in the world.

Based on forecasts from the Budget Papers, excise per stick can be expected to increase from slightly less than $1.50 per stick to over $1.70 per stick over the budget forecast period to 2028-29.

The stated rationale for the excise escalator was public health rather than revenue. Successive governments, supported by public health advocates, argued that steep annual increases were necessary to make tobacco products less affordable, particularly for young people. The National Tobacco Strategy 2023–2030 identifies affordability as the most effective lever to reduce smoking and sets the targets of reducing the national daily smoking rate to less than 10% by 2025 and to 5% or less by 2030.[8] Simon Chapman has similarly emphasised the role of taxation in driving down demand, describing it as the single most powerful measure to accelerate quitting and deter uptake, while rejecting the criticism that such measures are unfair to low-income smokers on the grounds that these groups are also the most responsive to price and therefore gain the greatest health benefits from quitting.[9] Within this framing, declines in reported daily smoking are regarded as evidence of policy success; whether substitution into vaping, illicit tobacco, or other recreational drugs is considered relevant to that measure of success appears to have been left as an open question.[10]

That omission is remarkable given the Strategy’s declared priorities. The National Tobacco Strategy 2023–2030 identifies 11 priority areas, including continuing to reduce affordability, strengthening regulation of supply and access, and tightening controls on e-cigarettes and emerging products.[11] Yet it offers no clear account of how these objectives interact or how substitution between products will be tracked. The lack of any framework for monitoring displacement — whether into vaping, illicit tobacco, or other nicotine delivery — sits uneasily beside aims such as ‘strengthen regulation to reduce the supply, availability and accessibility of tobacco products’ and ‘strengthen regulations on e-cigarettes and novel and emerging products’. In a policy that depends on price signals, disregarding substitution effects means overlooking part of the market response the Strategy itself is designed to provoke.

The question of whether these excise rises reduced the incidence of smoking is contested. There is evidence that the (unexpected) 25% increase in excise in April 2010 produced an immediate fall in smoking prevalence and a decline in legal sales volumes of around 10%, with further short-run effects after the first 12.5% rise in December 2013. One analysis reported step decreases of about 0.8 percentage points in smoking prevalence following each of these two interventions, although without any significant change in the long-run trend thereafter.[12] The same study noted that factory-made cigarette use fell, but roll-your-own tobacco use increased, especially among lower socioeconomic groups.

Other analyses, however, are less certain. A 2024 re-examination of the data concluded that the results are highly sensitive to the choice of baseline period.[13] Starting the trend in 2001 produces a modest decrease by 2017, but starting in 2005 implies no change, and starting in 2007 implies an increase by 2017. These authors argue that no study has conclusively shown that excise increases between 2010 and 2020 reduced smoking prevalence and consumption in Australia once this sensitivity is accounted for.

Despite this, official surveys do show that smoking prevalence has fallen markedly in recent years. According to the National Drug Strategy Household Survey, daily smoking declined from 24.3% of the population in 1991 to 8.3% in 2022–23.[14] [15] Between 2019 and 2023 alone, the daily rate fell from 11.6% to 8.8%, the steepest drop in three decades.[16] By contrast, however, recent Roy Morgan survey evidence suggests that the share of Australians aged 18 and over who smoke (or vape) has remained essentially flat over the past decade (17.7% in 2014 to 17.4% in 2025).[17]

What has changed is the composition of consumption; factory-made and roll-your-own cigarettes now account for just over 12% of consumption, vaping accounts for 7.5%, and reported use of illicit tobacco has risen sharply to 4.8%.[18] Roy Morgan notes that these self-reported figures likely understate the true size of the illicit market. Tobacco industry sources estimate “the illicit tobacco market now makes up 64% of all tobacco consumed in Australia and 82% of the total nicotine consumed”.[19]

Taken together, the data confirm that while legal cigarette sales have declined, total nicotine use has not fallen by the same margin; instead, consumption has shifted toward vaping and illicit tobacco. The combined evidence implies that the tax has reached the point of diminishing returns as a health measure. If total nicotine consumption remains stable while legal sales collapse, the policy’s effect is not to eliminate demand but to redirect it into untaxed and unregulated channels. In that sense, the excise escalator has become less a tool of public health than an incentive for substitution and illicit supply.

Similarly, the National Wastewater Drug Monitoring Program commissioned by the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission and administered by the University of Queensland and the University of South Australia reports, “The August 2024 results have nicotine consumption around the long-term regional and capital city average levels. Consumption of nicotine has increased over the life of the Program” (emphasis added).[20] The program reports data from June 2017 to October 2024. To be fair, the measured wastewater nicotine would include nicotine from nicotine replacement therapy and legally sourced vapes.

For some years, however, the policy did appear to work as intended – by official measures smoking prevalence appeared to be falling. In addition to data from the National Drug Strategy Household Survey, the Australian Bureau of Statistics reports that Household Final Consumption Expenditure on tobacco products declined in real terms from $84.9 billion in 1989-90 to $13.5 billion in 2024-25.[21] Surprisingly, the Commonwealth had budgeted to raise $11.6 billion in tobacco excise revenue in 2024-25.

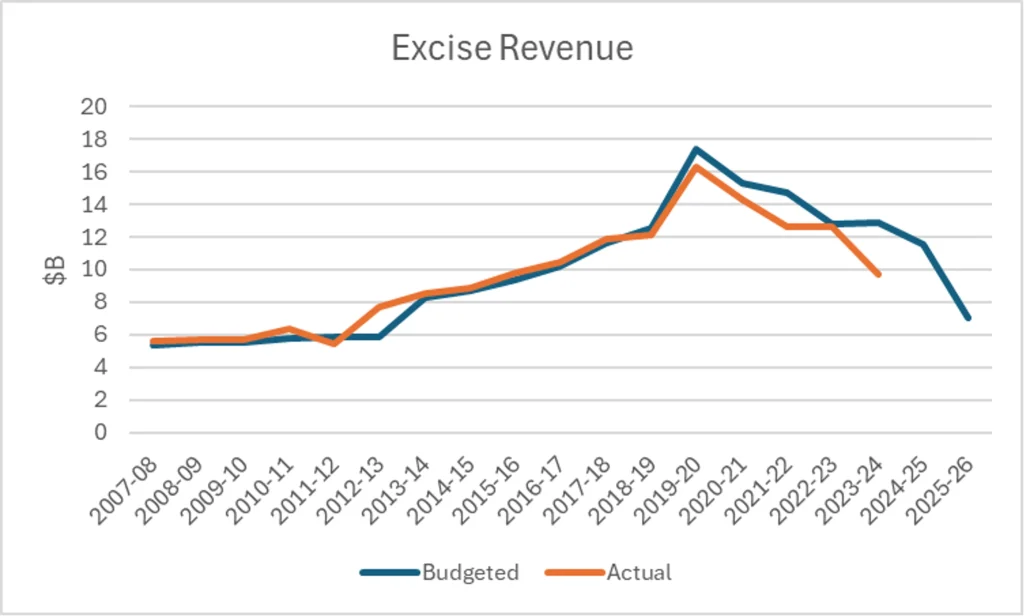

Furthermore, excise revenue showed massive increases in revenue raised. In 2019–20 the revenue pattern changed dramatically. Budget forecasts began to overshoot actual receipts.[22] The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) reported a net tobacco tax gap – the share of duty not collected – of about $2.7 billion in 2022–23, with roughly $0.4 billion attributed to illicit domestic production and the rest to illicit importation.[23]

At the same time, illegal markets for tobacco expanded and turned violent. Police in several states created specialised taskforces, such as Taskforce Lunar in Victoria, to tackle organised crime, arson, and extortion linked to illicit tobacco.[24] Fire services reported repeated attacks on shopfronts and neighbouring buildings, and insurers raised premiums or withdrew cover for affected businesses.[25]

The sequence is clear. A long campaign of advertising and branding bans and excise increases initially reduced smoking and boosted excise revenue. But as taxes kept rising and the legal market shrank, a tipping point was reached. A large criminal market emerged, legal sales fell faster than expected, and revenue forecasts collapsed.

Finally, it should be noted that while legal tobacco use has fallen sharply but the broader data suggest that nicotine consumption has increased, there has also been substantial rising use of other recreational drugs. National survey evidence confirms the decline in daily smoking, yet also records steady growth in cannabis, cocaine, and ecstasy use over the past two decades, with cannabis remaining the most widely used illicit drug and cocaine use doubling since the early 2000s.[26] Furthermore, recent econometric evidence indicates that the relationship between tobacco and cannabis varies across the life cycle.[27]

For younger Australians, the two substances are economic complements, such that higher tobacco prices reduce cannabis participation. For older Australians, however, the relationship reverses, with higher tobacco prices associated with increased cannabis use, implying substitution in later life. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare likewise reports that illicit drug consumption has risen overall, with marked increases among younger adults.[28] Wastewater analysis reinforces this picture: between August 2023 and August 2024, aggregate consumption of nicotine rose to above long-term averages, while national consumption of methylamphetamine, cocaine, MDMA, and heroin increased by 34% to 22.2 tonnes, the highest annual figure since monitoring began in 2016.[29] Taken together, the evidence suggests that the apparent decline in smoking has not occurred in isolation but rather against a background of rising nicotine intake and greater use of alternative recreational substances.

This recent history frames the analysis that follows. The next section explains, using standard economic theory, how the Ramsey–Pigouvian trade-off helps to understand where excise stops being corrective and starts becoming counter-productive.

The Ramsey–Pigou trade-off

Two early 20th-century Cambridge economists still frame how economists think about taxing tobacco. Frank Ramsey, writing in 1927, asked how a government could raise a given amount of revenue while causing the least loss to the economy. His answer was to tax goods where demand is relatively inelastic — that is, where people buy almost as much even when prices rise. A tax of that kind raises money without greatly distorting behaviour. Arthur Cecil Pigou, a near contemporary, focused instead on “externalities”, the costs or benefits imposed on others that are not reflected in market prices. In his 1920 book The Economics of Welfare, Pigou argued that when private transactions spill over negatively onto others, a corrective tax equal to the unpriced cost can bring private and social costs into line.

Ramsey’s principle supports tobacco excise as a way to fund government. Economists describe the demand for tobacco as relatively inelastic; people slowly reduce consumption when prices rise. A moderate tax therefore yields stable revenue with little impact on economic behaviour. Pigou’s principle offers a different justification. Smokers impose costs on themselves and on others beyond the private price they pay. In Pigouvian theory a tax internalises those additional costs.

What are the unpriced costs of smoking? The first is what economists now call an ‘internality’. A person may undervalue the harm that smoking today will cause their older self. The health consequences of long-term smoking — cancer, heart disease, reduced fitness — occur decades later and are easy to discount. A tax can act as a self-control device, encouraging people to take those future harms into account. The second is the cost to the publicly funded health-care system. Medicare and the state hospital networks pay for a large share of treatment for smoking-related disease. To the extent these costs are not recovered through insurance premiums or co-payments, they represent a fiscal externality. The third is the effect on others through second-hand smoke. Non-smokers exposed to smoke at home, in workplaces, or in public places face increased risks of respiratory and heart disease. These are direct physical externalities that ordinary market prices do not reflect.

What matters here is that these two principles of taxation can conflict. The logic of Ramsey taxation is to raise revenue efficiently. The logic of Pigouvian taxation is to reduce smoking and recover the costs it imposes on the health system and others. At low rates of taxation, the tension is mild. At high rates it becomes serious. A Ramsey tax stops being valuable at the point where it raises the desired revenue with minimal distortion. A Pigouvian tax stops being valuable once it has priced in the genuine external costs. Beyond those points the tax is no longer efficient or corrective; it becomes coercive.

Figure 3 shows the evolution of tobacco excise revenue in Australia since 2007-08. Revenue grew strongly through the period of regular annual increases, then flattened and began to undershoot Budget forecasts after 2019–20.

Figure 3: Tobacco Excise Revenue (2007-08 – 2025-26)

Source: Budget Paper 1 (various)

If smoking prevalence has indeed declined as official surveys show, it is plausible that the external costs of smoking have also declined. Yet in 2013 the Commonwealth legislated four annual 12.5% increases in tobacco excise, later adding 5% annual increases from September 2023. The health rationale had reduced, while the fiscal temptation to keep lifting rates remained strong. In the short run, high excise kept revenue rising because demand is slow to adjust.

But inelasticity is not infinite. The tax had moved beyond the range justified by either Ramsey efficiency or Pigouvian correction. Instead of improving health or raising predictable revenue, it created rents for smugglers and incentives for organised crime. By 2019–20 legal sales were shrinking faster than Treasury expected, Budget forecasts were consistently overshot and revised down, and the Australian Taxation Office reported a net tobacco tax gap of about $2.7 billion for 2022–23, including around $0.4 billion from domestic diversion and unlicensed production. The social costs of illicit supply — enforcement, violence, lost trade, and hardened insurance markets — now outweigh any further health benefit from higher rates.

Understanding the Ramsey–Pigouvian trade-off clarifies the policy choice. A tax can be a tool for efficient revenue raising or a way to make prices reflect external costs, but it cannot serve both masters indefinitely. Australia has reached the point where the marginal social cost of further excise rises exceeds the marginal benefit. The next section explains why this outcome was predictable once the power to set the tax was separated from the responsibility for dealing with its consequences.

Public choice and the trade-off between coercion and disorder

Economic theory can only take us so far. To understand the challenges of tobacco control we need to examine public choice theory. Instead of assuming a single benevolent planner as standard economic theory does, public choice begins with understanding the incentives bureaucrats and decision-makers face. In Australia those incentives encourage the Commonwealth to overuse the excise lever and underinvest in inland enforcement.

The Commonwealth sets the excise rate, collects the revenue, and controls border operations through the Australian Border Force. States and territories run the health systems that treat smoking-related disease and fund the police, fire services, courts, and prisons that respond to illicit trade, arson, and extortion. Local retailers and communities bear the cost of property damage, lost trade, and higher insurance premiums. It is important to emphasise that insurance premiums have not only increased for tobacco retailers but for other businesses that are either co-located or located in the close vicinity of tobacconists.[30] This division of responsibilities creates what economists call a vertical fiscal externality; one level of government sets a tax but does not face the full marginal cost of doing so.[31] It is a classic cost-shifting problem. Canberra can claim the revenue and the political credit for being tough on smoking, while the downstream costs are imposed on others.

The result is somewhat predictable. The Commonwealth has an incentive to keep lifting excise and to focus on the parts of enforcement it controls and can publicise — container inspections, border seizures, and dramatic press conferences. States, who bear most of the policing and health costs, have no claim on excise revenue. Their incentive is to spend cautiously on inland compliance and to hope that the Commonwealth will carry the political burden.[32] Each level of government can blame the other when illicit markets expand.

Recent remarks by the New South Wales Premier underscore how these fiscal and enforcement divisions now play out in practice. In November 2025, Premier Chris Minns publicly attributed the resurgence of tobacco use and the spread of illicit sales to Commonwealth excise policy. He observed that smoking “has genuinely returned to 1991 levels”, pointing out that while a legal packet of twenty cigarettes now costs about $50, an illegal packet sells for roughly $13. Minns stated that NSW had been forced to divert police resources to contain the problem “because we can’t allow this to run rampant”, describing the outcome as a “subsidised, cheap, widely available, ubiquitous tobacco industry that is untaxed”. [33] Just days later, the New South Wales Health Minister Ryan Park called on the federal government to lower tobacco excise rates, “We do need help from the federal government in relation to lowering the excise because that has created essentially a distorted market. And that’s not good for anyone when we’re trying to get on top of it”.[34]

This institutional misalignment can be understood through the institutional theory of regulation first proposed by Harvard economist Andrei Shleifer and co-authors.[35] They argue that every society faces a trade-off between disorder (private predation such as crime and evasion) and dictatorship (coercion by the state). Good institutions minimise the sum of these two costs. Too little state capacity and predation thrives; too much, and enforcement itself becomes oppressive and costly. Tobacco control in Australia has shifted towards very high levels of coercion — strict bans and high taxes — but without the enforcement capacity to manage disorder. Tobacco control in Australia displays the classic signs of disorder; private actors are using violence to capture rents created by high taxes, enforcement gaps, and regulatory gaps. Each increase in excise or further marketing restriction adds to the coercive aspects of the policy. The result is rising coercion and rising disorder at the same time.

Economists describe the adaptive tactics of illicit suppliers as repugnant innovation[36] and evasive entrepreneurship.[37] Repugnant innovation creates products or supply chains that meet consumer demand while sidestepping legal prohibitions — for example, unlicensed chop-chop production or sophisticated counterfeit packaging. Evasive entrepreneurship finds ways to avoid the tax altogether, such as diverting duty-suspended stock into the domestic market without paying excise. Both flourish when legal prices are far above production costs and the likelihood of detection inland is low. As Adam Smith observed in 1776, “An injudicious tax offers a great temptation to smuggling”.[38] Here Australia has echoed the 1990s tobacco smuggling crisis in Canada, where high levels of tobacco tax resulted in massive increases in smuggling and criminality. It has been estimated that in 1994, 60% of cigarette consumption in Quebec had been smuggled into Canada.[39] Eventually, the Canadian federal government and provincial governments lowered their tobacco taxes.[40]

The fiscal and social consequences follow. Legal sales shrink faster than Treasury forecasts, so excise revenue repeatedly undershoots the Budget. Violence over black-market profits imposes heavy costs on police, courts, insurers, and local communities. Yet none of these costs are borne by the Commonwealth or the departments that recommend the excise rate or oversee public health at the federal government level. They are instead loaded onto state budgets and the private sector.

Seen through the lens of public choice and the disorder–coercion trade-off, Australia’s tobacco control regime is not an accident of bad luck. It is the predictable outcome of a system that rewards the Commonwealth for aggressive taxation while leaving others to deal with the disorder that aggressive taxation creates. In the 2025-26 Budget, however, the Commonwealth has allocated a mere $40 million over two years to the States and Territories to combat the resulting illicit-tobacco trade.[41] The payment, set to expire after 2026–27, is less a solution than an admission that the problem has been devolved to the States. To put that $40 million into context, it has been estimated that organised criminals are earning $13 million per day — more than the Commonwealth’s entire two-year contribution in less than four days.[42] The next section quantifies the fiscal cost of this drift by estimating how much excise would have been collected had the illicit market not taken hold and how much those hidden costs add to the real price of current policy.

How much revenue is missing?

The previous section explained why Australia’s tobacco control regime rewards coercion without controlling disorder. One way to measure the cost is to ask how much excise would be collected if every cigarette smoked in Australia were taxed as intended. This section provides two estimates of that excise revenue loss.

In the first instance I rely on Treasury forecasts of tobacco excise. I assume that Treasury have a viable workable and (previously) accurate model of the Australian tobacco market. Furthermore, that the Treasury would update that working model with a lag. In this instance, we can simply observe the forecast errors from the budget papers to estimate the foregone excise revenue.

In the 2025-26 Budget Papers, the Commonwealth estimated excise revenue for that year to be $7 billion. It also forecast tobacco excise revenue out to 2028-29. It then reported ‘actual’ excise revenue to have been $9.7 billion in the 2023-24 financial year. In the 2020-21 Budget Papers the Commonwealth had forecast tobacco excise to be $15.3 billion. The forecast error is a negative 36.6%. Prior to 2019-20 tobacco excise had usually raised much more revenue than was budgeted. After 2020-21, excise revenue declines very rapidly and forecast errors are both negative and growing. This is very much an upper-bound of the magnitude of the revenue loss — $5.6 billion in 2023-24. If current forecasts eventuate the forecast error will be $7.9 billion in 2024-25.

By contrast, the ATO tax gap analysis provides a lower bound to the magnitude of the tax-loss associated with the current tobacco control policy. The Australian Taxation Office publishes an estimate of the net tobacco tax gap — the difference between the excise that should have been collected if all tobacco were taxed correctly and the amount actually received.[43] The ATO constructs this estimate from national consumption surveys, import and production data, and enforcement records of seizures and duty recoveries. The methodology assumes that if all currently untaxed tobacco were brought into the legal system, total consumption would remain the same. It therefore treats every untaxed cigarette as if it would still be smoked at the higher legal price. This is an important point. The ATO’s net gap is a static measure of potential revenue.

In the absence of an illegal market and in the presence of Pigouvian pricing policy some smokers would cut back or quit rather than pay the higher price. To estimate what revenue the Commonwealth could realistically expect if the illicit market were eliminated, we need to account for that behavioural adjustment. A simple way to do this is to set a behavioural adjustment range. At the low end, suppose only about 30% of current illicit consumption would continue if fully taxed. At the high end, assume about 70% would continue.[44]

Applying these bounds to the ATO’s latest estimate illustrates the scale of the loss. For 2022–23 the ATO puts the net tax gap at roughly $2.7 billion. If all that illicit consumption had been taxed, the theoretical upper limit of extra revenue is $2.7 billion. After allowing for behavioural adjustment, the amount that could plausibly have been collected lies somewhere between roughly $0.8 billion and $1.9 billion. Repeating this exercise for earlier years yields persistent and growing shortfalls in expected excise revenue.

These figures are conservative. They count only foregone excise. They do not include the added burden on state police and courts, the costs of arson and insurance withdrawals, or the losses to legitimate retailers. Nor do they capture the longer-term decline in tax morale or the erosion of respect for the rule of law.

This counterfactual analysis makes the hidden costs of policy failure visible. It shows that the Commonwealth’s reliance on ever-higher excise has not only fostered a violent black market but has also reduced the very revenue it was meant to raise.

Policy Recommendations

The evidence so far shows that Australia’s tobacco control strategy is no longer delivering on its own stated goals. Excise has moved well beyond the range justified by either efficient revenue raising or the pricing of genuine external costs. Revenue is falling short of forecasts, the tax gap is widening, and the violent black market continues to grow. The problem is not bad luck. The issue is not that tobacco control lacks purpose, but that its institutional design provides no feedback when the policy begins to fail. It is built into the way responsibilities and incentives are divided between the Commonwealth and the states. Policy must now be reshaped to bring tax levels, enforcement capacity, and stated objectives back into line.

Before any further excise increases are considered (including regular indexation), policy makers should establish what is actually happening in the market. That requires independent tracking of price and availability for both duty-paid and illicit tobacco, regular monitoring of substitution into vaping and other nicotine delivery, transparent reporting of inland enforcement outcomes by state, and a consistent reconciliation between Budget forecasts and ATO tax-gap estimates. Without this evidence, excise decisions will remain based on assumptions rather than outcomes.

The first requirement is clarity about purpose. Tobacco control cannot remain both a public health programme and a revenue measure without undermining itself. If the aim is to reduce smoking-related disease, states should logically lead because they run the health systems and police forces that carry the costs. But the Australian Constitution forbids the states from levying an excise tax. That means they cannot use a Pigouvian tax to recover health costs, even if they wanted to. The Commonwealth alone can impose the tax, and that fact makes the need for clear institutional design even stronger. If the aim is primarily health protection, the Commonwealth should support state-level harm-reduction and inland enforcement, and accept that tax increases beyond the Pigouvian range cannot be justified merely as health measures. If the aim is to raise revenue, the Commonwealth should also accept full responsibility for the costs its policy creates, including contributions to state policing and justice costs. A decision on purpose must come first, because without it there is no clear test of success and no way to align responsibility with cost.

Given the mixed evidence on whether recent excise rises have reduced total nicotine use, policy makers should commission a short, independent review to settle the key empirical questions set out above. Until that review reports, any increases in excise are best deferred; the Commonwealth should focus on inland enforcement, data transparency, and evaluation. If the review confirms that high excise is undermining both health and revenue by enlarging the illicit market, the rate should be brought back within a clearly specified Ramsey–Pigouvian range, with matched funding for state enforcement.

Excise itself needs to be stabilised within a Ramsey–Pigouvian range — high enough to cover the measurable external costs of smoking and provide predictable revenue, but not so high that it systematically undercuts its own base. That means pausing the current annual increases and setting a long-term path that reflects a realistic assessment of smoking prevalence and enforcement capacity. The ATO’s tax-gap estimates, combined with Budget forecast errors, provide the evidence needed to judge where that ceiling lies.

Enforcement also has to be rebalanced. Border seizures remain important but can no longer carry the load. The ATO estimates that a significant share of the tax gap now comes from domestic diversion and unlicensed production. Inland enforcement —- licensing, inspections, and intelligence work — needs to be strengthened and harmonised across states. High coercion without matching capacity simply feeds disorder.

Finally, the incentives between governments must change. The current division of labour gives the Commonwealth every reason to overuse the tax and leaves the states to bear the downstream costs.[45] Without a clear allocation of responsibility, each level of government can blame the other while the illicit market grows. A new intergovernmental arrangement should make it explicit that the level of government that sets the tax is also responsible for funding the enforcement and public costs it creates. This is not a call for revenue sharing but for institutional clarity.

Taken together these steps would turn tobacco control back into a coherent policy. They would bring excise rates back within an economically defensible range, align enforcement with the real sources of leakage, and remove the cost-shifting incentives that now drive over-taxation and under-enforcement. Above all, they would restore credibility to a policy that is supposed to protect health and raise revenue but has come to reward neither.

Concluding thoughts

While the policy recommendations set out here are both modest and sensible, they nonetheless will be viewed as being controversial.

Public-health advocate Simon Chapman AO, for example, argues that cutting tobacco excise would not eliminate Australia’s black market because the price gap is far wider than any politically feasible tax reduction could close.[46] He points out that illicit tobacco was widespread well before the steep tax rises that began in 2012 and that countries with much lower tobacco taxes also have significant black markets. Using simple price comparisons, he shows that even rolling excise back to 2019 or 2015 levels would still leave the retail price of duty-paid cigarettes well above the $8–10 a pack commonly charged for illicit tobacco. Proposals to find a ‘sweet spot’ rate therefore rest on unrealistic assumptions about industry and retail margins. Chapman concludes that tougher enforcement, not tax cuts, is the credible way to deal with illicit supply.

The former head of the Australian Border Force’s Tobacco Strike Team, Rohan Pike, also advocates greater enforcement: “This is Australia, a developed country with an established law enforcement regime. To have an illicit tobacco rate of 60% and rising is appalling. This is a self-inflicted policy crisis that needs action now.”[47]

Both Chapman and Pike make plausible and important arguments. What is clear, however, is that resolving the tobacco war crisis is not going to turn on a tax reform or enhanced policing — although they must both play a role is restoring the rule of law to Australian tobacco control policy. What is important is to address the federal division of labour in setting policy and the distortions that fiscal federalism introduce in maintaining law and order. A coherent tobacco policy should now aim to match fiscal realism with public-health intent; only then will Australia’s success in reducing smoking translate into a durable, lawful, and governable outcome.

Endnotes

[1] Greenhalgh, EM, Scollo, MM and Winstanley, MH. Tobacco in Australia: Facts and issues. Melbourne : Cancer Council Victoria; 2024. Chapter 11. Available from https://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/

[2] The exception being Formula 1 racing where tobacco advertising ceased in 2006.

[3] Bayly, M. and Scollo, M.M., 2025, 13.6 What tobacco taxes apply in Australia? in Greenhalgh, E.M., Scollo, M.M. and Winstanley, M.H. (eds), Tobacco in Australia: Facts and Issues, Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria, Section 13.6.3.1.

[4] Greenhalgh, Scollo, and Winstanley, as above, Chapter 13.

[5] https://www.ato.gov.au/businesses-and-organisations/gst-excise-and-indirect-taxes/tobacco-and-excise/excise-duty-rates-for-tobacco

[6] See Davidson, S. and De Silva, A., 2014. The plain truth about plain packaging: An econometric analysis of the Australian 2011 Tobacco Plain Packaging Act. Agenda: A Journal of Policy Analysis and Reform, pp.27-43, and Davidson, S. and De Silva, A., 2018. Did recent tobacco reforms change the cigarette market?. Economic Papers: A journal of applied economics and policy, 37(1), pp.55-74.

[7] Greenhalgh, Scollo, and Winstanley, as above, Chapter 13.

[8] Department of Health and Aged Care, National Tobacco Strategy 2023–2030, Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023, pp. 9–10.

[9] Simon Chapman, Quit Smoking: Weapons of Mass Distraction, Sydney: Sydney University Press, 2022, pp. 259–61.

[10] As I demonstrate below, it is very clear that some substitution to other forms of nicotine consumption has occurred.

[11] Department of Health and Aged Care, National Tobacco Strategy 2023–2030, Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023, p. 9.

[12] Wilkinson, A.L., Scollo, M., Wakefield, M.A., et al., 2019. Smoking prevalence following tobacco tax increases in Australia between 2001 and 2017: an interrupted time-series analysis. Lancet Public Health, 4, e618–27; but also see also correspondence: Jegasothy, E. and Markham, F., 2024. Smoking prevalence following tobacco tax increases in Australia. Lancet Public Health, 9(7), e418.

[13] Jegasothy, E. and Markham, F., 2024. Correspondence: Smoking prevalence following tobacco tax increases in Australia. Lancet Public Health, 9(7), e418.

[14] https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/behaviours-risk-factors/smoking/overview

[15] National survey measures of smoking, such as the National Drug Strategy Household Survey, do not distinguish between taxed and untaxed tobacco. Respondents reporting that they “currently smoke” may be using either legally or illegally supplied products. Reported prevalence therefore reflects total tobacco use, not just duty-paid consumption.

[16] Martin, J. and Jegasothy, E., 2025. Fanning the Flame: Analysing the Emergence, Implications, and Challenges of Australia’s De Facto War on Nicotine. Harm Reduction Journal, 22:42, pp. 2–3. The decline was fastest among younger Australians, coinciding with a sharp increase in vaping uptake, suggesting a substitution effect rather than a gateway effect.

[17] https://www.roymorgan.com/findings/9937-cigarette-smoking-in-australia-press-release

[18] These figures reflect self-reported prevalence rather than volumes of tobacco or nicotine consumed. The term ‘consumption’ here refers to usage patterns, not quantitative intake.

[19] ABC News, “As illicit tobacco sales rise into the billions, economist Arthur Laffer puts blame on high tobacco taxation rate”, 14 October 2025.

[20] Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission, National Wastewater Drug Monitoring Program. Report 24, pg. 59. https://www.acic.gov.au/publications/national-wastewater-drug-monitoring-program-reports/report-24-national-wastewater-drug-monitoring-program

[21] ABS. Cat. 5206.0 Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product, Table 8.

[22] See below for more discussion.

[23] Australian Taxation Office, Tobacco tax gap: Latest estimates and findings 2022–23, Canberra, 2024. https://www.ato.gov.au/about-ato/research-and-statistics/in-detail/tax-gap/q-z-tax-gaps/tobacco-tax-gap/latest-estimates-and-findings

[24] Herald Sun, “$13m a day: Organised criminals’ tobacco wars exposed”, 28 February 2025. https://www.heraldsun.com.au/truecrimeaustralia/13m-a-day-organised-criminals-tobacco-wars-exposed/news-story/7151abdb6f6c5145a382de10a2ce9bc6

[25] ABC News, “Coburg and Footscray stores targeted by arsonists as Victoria’s tobacco store fires rise”, 7 June 2024; ABC News, “Insurers say it’s become ‘almost impossible’ to find cover for tobacconists after string of arson attacks”, 6 June 2025.

[26] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2022–23: Data Tables – Tobacco, Smoking, Canberra: AIHW, 2023.

[27] Harris, M.N., Singh, R.B. and Srivastava, P., 2024. Cannabis and tobacco: substitutes and complements. Journal of Population Economics, 37, pp.75–106.

[28] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Alcohol, Tobacco & Other Drugs in Australia, Canberra: AIHW, 2023, pp. 16–18.

[29] Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission, National Wastewater Drug Monitoring Program: Report 24, Canberra: ACIC, 2024, p. 6.

[30] The Australia, “Revealed: True impact of illegal tobacco on insurance premiums”, 20 October 2025, https://www.theaustralian.com.au/nation/revealed-true-impact-of-illegal-tobacco-on-insurance-premiums/news-story/e2d640c783f2d163b4c848aa3ab712aa

[31] Keen, M., 1998. Vertical tax externalities in the theory of fiscal federalism. IMF Staff Papers, 45(3), pp.454–485.

[32] https://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/researchpapers/Pages/tobacco-licensing-schemes.aspx

[33] Alexandra Smith, NSW illicit tobacco: St Leonards stores raided and closed under new powers, Sydney Morning Herald, 4 November 2025

[34] Mornings with Hamish MacDonald, https://www.abc.net.au/listen/programs/sydney-mornings/mornings/105977930, 11 November 2025.

[35] Djankov, S., Glaeser, E., La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F. and Shleifer, A., 2003. The new comparative economics. Journal of Comparative Economics, 31(4), pp.595–619. See also Davidson, S., 2018. Some (micro) economics of regulation. In Australia’s Red Tape Crisis: The Causes and Costs of Over-Regulation. pp. 69-79. Connor Court Publishing.

[36] Allen, D.W., Berg, C. and Davidson, S., 2023. Repugnant innovation. Journal of Institutional Economics, 19(6), pp.918-929.

[37] Thierer, A., 2020. Evasive entrepreneurs and the future of governance: How innovation improves economies and governments. Cato Institute.

[38] Adam Smith, 1776 [1976], An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of Nations, University of Chicago Press, p. 351.

[39] https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/tobacco-firms-to-pay-550m-over-smuggling-1.902510

[40] As the same time, it is important to emphasise that there are differences between the Canadian example and Australia. Smuggling in Canada was complicated by industry involvement and exemptions that Canadian First Nations have in paying various taxes.

[41] Commonwealth of Australia 2025. Budget Paper No. 3: Federal Financial Relations 2025–26.

[42] Herald Sun, as above.

[43] Australian Taxation Office, as above.

[44] International evidence consistently finds that the long-run price elasticity of demand for cigarettes lies between about –0.3 and –0.7. In other words, a 10% price rise eventually cuts consumption by roughly 3 to 7%. See for example Chaloupka, F.J. and Warner, K.E., 2000. The economics of smoking. Handbook of Health Economics, 1, pp.1539–1627; IARC, 2011. Effectiveness of tax and price policies for tobacco control. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; and World Bank, 2019. Tobacco Tax Reform: At the Crossroads of Health and Development. Using behavioural‐adjustment bounds of 30 to 70% for illicit consumption brought under taxation is therefore conservative and consistent with these international estimates of price responsiveness.

[45] The recent comments by NSW Premier Chris Minns, who blamed the federal excise for fuelling a “subsidised, cheap, widely available, ubiquitous tobacco industry that is untaxed”, underscore that the costs of enforcement now fall squarely on the states.

[46] https://simonchapman6.com/2025/08/07/lowering-tobacco-tax-to-make-illegal-tobacco-sales-disappear-overnight-at-last-we-have-a-proposed-figure-and-its-an-absolute-doozie/

[47] https://www.theaustralian.com.au/health/wellbeing/australias-tobacco-commissioner-rules-out-tax-cuts-to-combat-billiondollar-illicit-cigarettes-black-market/news-story/bf50cb9756cf3f49da33ea180a2fcdf0