Executive Summary

In a recent article, prominent foreign affairs author James Mann argued that ‘The idea of a powerful United States bringing China into the existing system is fading’ and concluded:

The idea of integrating China into a U.S.-led world order was a chimera from the start. So, instead of pursuing vague and larger purposes, we should simply pursue our own interests, as China does. We can stop pretending that those interests coincide. There is no need to sign grand statements about Sino-American cooperation when they don’t reflect the underlying reality between the two countries.i

This paper argues that America’s capacity to ‘manage’ China and encouraging it to rise as a ‘responsible stakeholder’ within a US-led system is indeed failing. China is too big, too proud, too and independent-minded to be ‘tamed.’ Although Beijing’s behaviour has been shaped and tempered by its interaction with the United States and from being a beneficiary of the existing US-led regional and global order, it is also a ‘free-rider’ and an occasionally subversive participant within this order. While the American approach of encouraging China to rise as a ‘responsible stakeholder’ has been effective in influencing Beijing’s short-term tactical choices, the strategy has been much less successful in shaping China’s longer-term objectives. Far from gradually accepting American traditional pre-eminence in Asia, Beijing is simply ‘biding its time’ while it builds what Chinese officials and strategists call China’s ‘comprehensive national power.’

Taking a broader perspective shows that despite generally seeking cooperation rather than confrontation, China has long viewed America as its primary ‘strategic competitor’ and considers the competition for influence as a ‘zero-sum’ contest.

Although China may yet emerge as a ‘responsible stakeholder’ within a US-led system, this paper concludes by arguing that a more prudent and effective course for America is to explicitly recognise that ‘strategic competition’ with China is already occurring, endemic, and likely to intensify in the future. Recognising this reality is more likely to prolong American leadership in Asia. Paradoxically, accepting the reality that China is a ‘strategic competitor’ will also increase the likelihood that future competition is restrained, bounded and ultimately peaceful.

Introduction

In his opening speech at the 2009 US-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue, President Obama proclaimed that the US-China relationship will shape the twenty-first century and issued a clarion call to both Beijing and his own administration:

Will nations and peoples define themselves solely by their differences or can we find common ground to meet our challenges?

He continued:

This dialogue will help determine the ultimate destination of that journey. It represents a commitment to shape our young century through sustained cooperation, and not confrontation?ii

The contemporary search for genuine strategic cooperation with China by George W. Bush in his second term and the Obama administration are largely based on the United States assuming that China is rising as a ‘responsible stakeholder’ within the US-led global security and economic system — characterised by open markets, security alliances, multinational cooperation, rule of law, and democratic community. Recognising that China has undoubtedly benefited more from the stable international environment over the past three decades than any other country, the current US framework is not designed to ‘contain’ China but to ‘shape’ its strategic objectives and tactical choices. As Thomas Christensen explains, American regional leadership ‘helps channel China’s competitive energies in more beneficial and peaceful directions,’ concluding ‘it is in China’s strategic interest as a rising power to exert greater effort to help maintain the system’ that has allowed it to rise in the first place.iii

This paper argues that although Beijing’s behaviour has been shaped and tempered by interaction with the United States and from being a beneficiary of the existing regional and global order, Washington’s capacity to ‘tame’ China is limited. Even though China is largely rising within the existing system, it is also a security ‘free-rider’ and an occasionally subversive participant within this system. While the framework has been useful in shaping Beijing’s short-term tactical choices, it has been much less effective in shaping or changing China’s longer-term strategic objectives. As an ‘insider,’ China is increasingly challenging American military and non-military pre-eminence by attempting to dilute American power, influence and alliances—with early but significant success. Indeed, my conversations with senior officials from key capitals in the region such as Tokyo, Seoul, Singapore, Hanoi, Jakarta, and Sydney (in addition to Washington) have all confirmed that rather than behaving as a constructive or a restrained power, China has emerged as a much more assertive and acerbic power since the onset of the global financial crisis in 2008.

More broadly, despite generally seeking cooperation rather than confrontation, China has long viewed the United States as its primary strategic competitor. Although Beijing recognises that the American presence currently provides much needed stability in Asia, its frequently stated goal of Asian preponderance is directly at odds with continued US leadership in Asia. Far from accepting Washington’s pre-eminence in Asia as permanent, Beijing has been simply ‘biding its time’ while building what Chinese officials and strategists call China’s ‘comprehensive national power.’

Finally, by denying the reality that China is both an economic partner and a strategic competitor, the United States is leaving itself few options should the ‘responsible stakeholder’ framework fail—besides hedging against alternate possibilities by maintaining a robust military and network of alliances. This is short-sighted since current Chinese strategy is precisely designed to dilute the strength of Washington’s alliances and ensure that the military, economic and political costs of possible American military action in Asia against China are prohibitive.

Although China may yet emerge as a ‘responsible stakeholder,’ this paper argues that a much more prudent course is to explicitly recognise that ‘strategic competition’ with China is endemic, whilst continuing to seek avenues for tactical cooperation on bilateral and global issues. Doing so is much more likely to prolong American leadership in Asia by directly counteracting Chinese initiatives designed to maximise its influence in Asia at the expense of Washington’s. If China continues to rise rapidly, then explicitly recognising the reality of strategic competition also makes it more likely that political, military and economic competition will be increasingly circumscribed and bounded over time rather than unrestrained and unpredictable.

China as ‘responsible stakeholder’

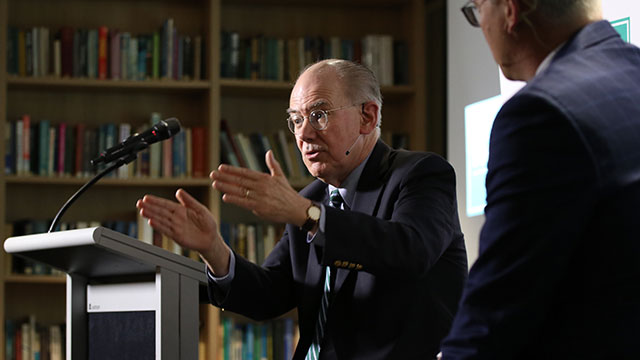

In January 2009, former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger argued that the US-China relationship needed to be ‘taken to a new level,’ and urged Washington to enlist Beijing in the US endeavour to shape ‘a new common destiny’ for the world.iv Zbigniew Brzezinski, the former National Security Advisor to President Jimmy Carter, went further. In the now famous opinion piece published in the Financial Times offering friendly advice to Obama, Brzezinski suggested that the two countries should move towards instituting an informal Group of Two (G2) to promote cooperation on a number of global issues such as nuclear non-proliferation, climate change, and economic recovery and developing solutions to the problem of ‘rogue states’ such as North Korea and Iran.v According to Brzezinski, the relationship between the United States and China had to be a ‘comprehensive partnership, paralleling our relations with Europe and Japan.’ Leaders of both countries should meet regularly to discuss not just bilateral relations but ‘the world in general.’

The G2 proposal recognises that a rising China will increasingly seek greater power and influence on the regional and global stage. The concept is remarkable because it explicitly elevated the US-China bilateral relationship to an unprecedented level with respect to China’s global importance and its importance to the United States. It is also noteworthy that this proposal—although not endorsed by the Obama administration—was implicitly built on previously prepared foundations.

In particular, several years before Brzezinski’s piece was published, the then US Deputy Secretary of State and current World Bank President Robert Zoellick put forward what was to become the still authoritative framework guiding Washington’s relations with Beijing. In September 2005, Zoellick called on China to be a ‘responsible international stakeholder.’ As Zoellick explained two years later, ‘given China’s success, its size, its rising influence … it has an interest in working with other major countries to sustain and strengthen the international system.’vi Given the need for cooperation, Zoellick hoped that ‘China and the United States will … sustain and strengthen the international order of political, economic, and security systems by working as mutual stakeholders, sharing responsibility.’vii

There have been other subsequent formulations to guide the US-China relationship, such as Deputy Secretary of State Jim Steinberg’s proposal for a ‘strategic reassurance’ bargain with Beijing.viii But unlike Steinberg’s hastily conceived formulation, Zoellick’s framework was no ‘fly by night’ concept. The ‘strategic stakeholder’ framework was announced only after careful thought and debate amongst State Department and National Security Council officials. Its spiritual roots reach back to Richard Nixon’s rapprochement with China in 1972,ix and its policy roots go back to the Bill Clinton presidency in the 1990s when substantial economic engagement with China began, culminating in China’s ascension into the World Trade Organisation in 2001. The framework—building on what experts previously referred to as ‘congagement’ — relies on credible realist and liberal foundations,x namely, that the most effective way to deploy superior American military and economic might is to ‘manage’ the rise of China (rather than prevent it). xi By offering China a ‘stake’ in the existing international and regional economic and political systems, Beijing is being encouraged to benefit itself by acting as a ‘responsible stakeholder’ and a status quo power within a US-led regional and global security and economic order.

Despite entering the Oval Office criticising the perceived foreign policy failures of the George W. Bush administration in Asia, President Obama has effectively endorsed and even expanded Zoellick’s framework. For example, the Strategic Economic Dialogues between Washington and Beijing (covering economic issues) that began under the Bush administration have been transformed into the Strategic and Economic Dialogues covering strategic and security in addition to economic matters. Officials in both Washington and Beijing openly consider the US-China relationship as the ‘most important one in the world.’ Notably, Jeff Bader, the Senior Director for Asia in the US National Security Council and President Obama’s ‘go to’ expert on Asia, has called China ‘an essential player on the global issues that are at the center of our agenda …’ and has repeatedly said that ‘the US cannot succeed without China’s cooperation’ on the most pressing global issues facing America.xii Indeed, despite ongoing problems and tensions in the bilateral relationship, the Obama administration continues to describe China as ‘the leading stakeholder’ in the US-led world order.

China’s ‘peaceful development’

If the ‘responsible stakeholder’ framework is the one used by Washington to describe how America prefers China to rise, a seemingly complementary concept emerged out of China two years before Zoellick’s famous formulation.

In 2003, Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao introduced the concept of China’s ‘peaceful rise’ in a speech to students at Harvard University, a term that was subsequently endorsed continually by Chinese President Hu Jintao.xiii The term was later changed to ‘peaceful development’ after members of the politburo successfully argued that the term ‘rise’ might cause alarm amongst other states.

‘Peaceful development’ has become the official strategic national objective of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The concept is designed to convince the world that China’s re-emergence poses little threat to existing stability and order. As Ye Zicheng, the director of Chinese studies at Beijing University, argues:

The biggest difference between the now ascendant China on the one hand, and Germany during World War I and Japan during World War II on the other, is that China has no intent to challenge the existing system through military expansion. Nor does it seek to create another system outside the existing system to engage in confrontation.xiv

It helps that some aspects of the doctrine of China’s ‘peaceful development’ are highly compatible with the American formulation of China as a ‘responsible stakeholder.’ For example, Beijing frequently argues that China’s rise leads to win-win economic opportunities for the rest of the world. China is heavily engaged in regional forums such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and recently activated a free trade agreement with it in February 2010. China is a member of almost as many regional and global institutions as is the United States. It overtook Germany as the world’s leading trading nation this year and holds around US$800 billion in US Treasury bonds and approximately US$1.4 trillion in US dollar assets overall. As Ye explains:

While it was necessary for the powers of the past to resort to military force because they could not achieve the goal of development using peaceful means … today, even though there are conflicts between China and the powers in the allocation of markets and resources, they can be worked out peacefully.xv

Many authors argue that whilst the potential for US-China conflict is genuine, official Chinese concepts such as ‘peaceful development’ and promoting a ‘harmonious world’ are fully compatible with the American preference for China to rise as a ‘responsible stakeholder.’ As Jia Qingguo and Richard Rosecrance argue, ‘China has gradually accepted the US-led world order and become a status quo power,’ relying especially on ‘trade and investment for national welfare and prestige, instead of military conquest.’xvi These authors draw comparisons between China’s modern rise to that of the United States in the nineteenth century and Germany and Japan in the post-World War II period in arguing that China is as likely to be a ‘responsible stakeholder’ in the current system as these earlier powers were vis-à-vis the British and then the American-led systems respectively.

Economic engagement with China has worked to the extent that the costs to China of overtly challenging or overthrowing the post-Cold War regional and global system in the foreseeable future will be enormous and probably prohibitive given the likelihood that this would lead to conflict with America and its allies.

However, many commentators such as Jia and Rosecrance fail to distinguish between Beijing’s desires to avoid military conflict with America from its apparent preparedness to engage in strategic competition with Washington. China remains a deeply insecure rising power within the US-led regional and global system and already sees itself in intense strategic, political, military, and even economic competition with Washington.xvii Chinese commentators frequently speak about the United States pursuing a ‘two-handed strategy’ of ‘engagement’ to promote regime change in China and ‘containment’ through security alliances and partnerships to stem China’s rise. Because Beijing sees US-China tension as ‘structural,’ it remains convinced that American policy will ultimately seek to contain Chinese power and influence as much as possible. As the paper argues, China’s ‘peaceful development’ concept should be treated as a prudent tactical approach devised by Beijing rising within a potentially hostile environment and vis-a-vis a much more powerful competitor. It does not represent an enduring commitment to remain a ‘responsible stakeholder’ within a US-led order.

None of this is to deny that tactical cooperation between Washington and Beijing will not continue. Indeed, the United States and China remain generally cooperative in a number of areas, especially given the close economic links between the economies of the two countries. However, the evidence that China is committed to becoming a ‘responsible stakeholder’ within a US-led system or order is weak. Future policy needs to examine the validity and effectiveness of any such framework and accept the reality that as far as Beijing is concerned, strategic competition is structural and already taking place between the two countries.

Reaching the limits of China as ‘responsible stakeholder’

America’s preferred model for managing rising powers is based on its experience with post-World War II Japan: an economically powerful and politically cooperative ally but strategically dormant and militarily inhibited. Realising that these restrictions could not be imposed onto China, the ‘responsible stakeholder’ approach is designed to achieve the next best thing: ‘manage’ China’s benign re-emergence and integration into the existing system. ‘Managing’ China’s rise as a ‘responsible stakeholder’ means more than just avoiding conflict with it. It entails Beijing committing to actively uphold and preserve the existing US-led order as China rises. However, the framework of encouraging China to be a ‘responsible stakeholder’ is ill-suited to China and failing for a number of reasons.

Confusing ‘means’ with ‘ends’

From the American point of view, the ‘responsible stakeholder’ approach is designed to structurally entrench China as a status quo power within the system since China has been allowed to emerge as beneficiary of the current US-led order. As China freely admits, it benefits enormously from the US naval role in the South China Sea, which keeps the peace and creates helpful conditions for trade and commerce to thrive.

However, Washington is erroneously assuming that it is shaping Chinese foreign policy and strategic goals and purposes.xviii In reality, Beijing is merely using the ‘responsible framework’ to further its own position and influence. While the United States devotes ships, troops and money to uphold the current American-led order in Asia, China benefits as a security free-rider in the region rather than as a trusted contributor. Internal debates within China reveal that Beijing is using the current period as a transient phase to bide its time while building what it terms Chinese ‘comprehensive national power.’ In particular, Beijing’s leaders and strategists do not accept the permanent pre-eminence of the American Seventh Fleet in the Pacific.

This is persuasively illustrated by the rapid increase in China’s military capacity. The country’s force modernisation and projection program has been growing at double digit rates each year since the early 1990s. As the current head of the Pacific Command, Admiral Robert Willard, admitted, ‘in the past decade or so China has exceeded most of our (previous) intelligence estimates of their military capability … They’ve grown at an unprecedented rate.’xix According to former National Security Advisor Stephen Hadley, China’s evolving military capabilities (fighter aircraft, missiles, and submarines) ‘seem designed to give China the option not just to act militarily against Taiwan without interference, but also to give China exclusive control over the South China Sea.’xx

Importantly, China’s ‘next generation’ force development and technologies (such as cyber-war capabilities and anti-satellite missiles) are specifically designed to counteract American capabilities and military networks in the region. Its submarine fleet is growing at around three new vessels every year, making it the fastest expanding fleet in the world. The numbers of Chinese submarines exceed US submarines stationed in the Pacific 4:1.xxi It has developed a large and lethal arsenal of conventional cruise and ballistic missiles, and new models (such as adaptations of the DF 21 missile) that are specifically designed to target US aircraft carriers from mobile launchers.xxii This rapid development of various forms of sea denial capabilities (submarines and DF21 missiles) are not compatible with a rising power willing to accept the pre-eminence of the American naval role in East Asia and the South China Sea.xxiii At the very least, China’s force modernisation and doctrine are cleverly designed to make the costs of military intervention in East Asia prohibitive for America.

This growing military capacity is significant since Beijing repeatedly claims around 80% of the South China Sea as its ‘historic waters.’xxiv Beyond the South China Sea, China has also set up naval ports, listening stations, logistics facilities and refuelling depots in waters belonging to Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Cambodia. This includes facilities in the Coco Islands, which lie only 18 kilometres north of the Indian naval base in the Andaman Islands.xxv It is constructing a waterway that extends from Yunnan province to the Bay of Bengal through the Irrawaddy River in Myanmar.xxvi These observations are at odds with surprisingly resilient arguments that China’s force modernisation program is simply focused on preventing Taiwanese independence xxvii or that China is primarily and overwhelmingly focusing on ‘domestic economic development’ for the next two decades.xxviii

Moreover, the common observation that China is simply acquiring a military capability that is commensurate with its rising economic strength is correct but irrelevant in this context. The point is that Beijing (quite legitimately) is not prepared to accept future American military dominance in the Pacific Ocean (and possibly Indian Ocean) and is already engaging in quiet military competition to eventually contest the military status quo.

More broadly, as China’s National Defense White Paper points out, the first two decades of the twenty-first century offer China a window of ‘strategic opportunity’ to build its comprehensive national power at the expense of competitors (read America).xxix This is repeated in transcripts handed to me of exchanges taking place during the National People’s Congress in both 2009 and 2010, where Chinese leaders and officials speak frequently about quietly seizing ‘windows of opportunity’ to build Chinese comprehensive national power at the expense of America.

The current approach to develop its military capacities without provoking conflict with a much more powerful competitor is consistent with previous examination of the body of Chinese strategic literature since the late 1990s.xxx According to the December 2009 edition of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences’ (CASS) Yellow Book, which assesses the ‘comprehensive national power’ of the top 11 nations in the world and is regarded as the authoritative document on informed Chinese views of the global environment, America comes out on top in every category except for ‘natural resources,’ while China is ranked seventh overall. One of the lead authors, Li Shaojun, points out that in addition to its military dominance America enjoys ‘unparalleled’ advantages in key categories such as economy, social and civil society, science and technology, geo-strategy, geography, and international institutions. This explains China’s preference for non-overt competition. It would be foolhardy to outwardly challenge a much more formidable America head-on.xxxi

Instead, China’s current American and regional strategy is based on the three axioms of Deng Xiaoping’s grand strategy: avoid conflict, build its comprehensive national power, and advance incrementally so as to not raise alarm. At its peril, the United States is ignoring the words of two prominent military strategists when they say that comprehensive national power is ‘the source of combat effectiveness’ and the ‘fundamental base for war preparations.’ A substantial comprehensive national power serves as a deterrent against other great powers interfering and acts as a defence against China being ‘controlled by hegemonists’xxxii (i.e. America). The Chinese view of comprehensive national power as an inherently zero-sum concept largely explains why Beijing is generally unwilling to devote significant political or financial resources towards pursuing regional and global agendas (such as the issues of North Korea and nuclear proliferation) that it believes primarily serve American interests.

Using multilateralism to undermining the US-led order

The ‘responsible framework’ approach relies on the belief that there is no alternative for emerging states but to rise within the existing order. Even so, the framework does not account for the fact that rising participants within it—especially the increasingly powerful ones—can circumvent or subvert the existing order and its rules as participants in multilateral forums from within. It is still an open question whether Beijing’s recent embrace of multilateral forums has softened and shaped Chinese objectives or simply shaped Chinese tactics as many realists believe. As an argument for the latter, in the transcript of conversations from the 2009 National People’s Congress in reference to international institutions, Chinese officials declared, ‘We will work with the Americans when we can, alongside them in rule making and institution building, and replacing them when useful and necessary.’ Furthermore, in my recent review of more than 100 strategic writings and internal memos written since the turn of the century, over four-fifths concern pushing a number of concepts or else creating using multilateral processes to bind, restrict, circumvent, or dilute American power and its military alliances.

Geo-strategically, Beijing’s attempts to create its alternative hub-and-spokes system in geostrategic vacuums in Central Asia, Indo-China and Africa are noteworthy. These relationships are not just about access to resources but the creation of alternative centres of strategic power and political voting blocs within existing international institutions. But it is the use of multilateralism that has been the more creative and effective tactic for China in extending its influence and circumventing and redesign the US-backed regional order in East and Southeast Asia.

In particular, China has cleverly promoted regional multilateralism as a key principle of its ‘peaceful development’ doctrine to bind and dilute American advantages in several ways. Its diplomats in Asia contrast China’s desire for multilateralism with America’s unilateralism.xxxiii They prefer the policy of ‘democratization of international relations,’ which entails that states should make decisions only after the conclusion of a multilateral process.xxxiv This is obviously to China’s advantage, since any process that recognises the existence of great powers having an equal say in regional affairs dilutes the advantage of America in the existing order. China’s rhetoric about ‘multilateralism,’ which is linked to its ‘harmonious world’xxxv concept of giving nations an equal say in collective decisions, seeks to promote a de facto multi-polarity by restricting US pre-eminence and freedom of action.

Furthermore, China’s proposed security structures are designed to undercut US influence and the viability of Washington’s hub-and-spokes model in Asia, which Beijing criticises frequently as ‘destabilising’ and a Cold War ‘relic.’ After all, Beijing (correctly) perceives Washington’s network of security allies and partners in Asia as a structure designed to both entrench American pre-eminence and restrict Chinese power and influence. In summarising Beijing’s position since the 1990s, prominent Chinese strategist, Wu Xinbo, argued in 2001 for a notion of regional ‘common security’ by playing down the importance of bilateral military alliances that are designed to ‘rattle’ the ‘sabre against a third party (i.e. China).’xxxvi This perspective is mirrored by more recent Chinese strategic writings.xxxvii Beijing is well aware that without American forces and fixed facilities permanently stationed in Japan and South Korea, sustaining America’s traditional military capabilities in East Asia will be impossible.

The desire to gradually dilute American influence explains China encouraging an alternative power structure that undermines the American role in the region; for example, by promoting ASEAN+3 (which includes the ASEAN states and China, Japan and South Korea but excludes America) as the primary security forum, and backing the East Asian Summit (which also excludes America) as the pre-eminent regional forum. Indeed, China has been subtly pushing ‘Asian regionalism’—political and strategic—in order to eventually exclude America from the region. This is a clever tactic since any attempts by Washington to block regional integration would exacerbate anti-Americanism in many parts of Asia.xxxviii

The folly of attempting to mould China’s ambitions

The ‘responsible stakeholder’ framework assumes that Chinese interests and ambitions are not pre-existing or pre-determined but ‘plastic’ and can be moulded according to the circumstances of China’s rise. But this argument ignores compelling historical and contemporary evidence that China is predisposed to seek leadership of Asia and to recast regional order according to its preference. After all, the country’s political, strategic and social elites see reclaiming China’s past historical and cultural pre-eminence in Asia as inseparable from its modern destiny. As CCP leaders repeatedly point out, China has been the dominant civilisation in Asia for 3,000 years and has had the largest economy in the world for 18 of the past 29 centuries. Yet, after a period of instability and chaos, it is emerging within an American-led regional order that it had no part in defining or shaping. There is now a broad consensus amongst CCP officials and social elites that regaining China’s paramount place in the region is inextricable from reversing its 150 years of humiliation at the hands of Western and Japanese powers. The explicit long-term objective of achieving ‘preponderance’ differs amongst the leadership only with respect to how long it might take.

Importantly, Chinese leaders and strategists believe that becoming the ‘preponderant power in Asia’ will require the substantial diminution, if not outright elimination, of the American presence in countries such as Japan, South Korea and the Philippines.xxxix As senior CASS researcher Yizhou Wang puts it, the ‘US military presence in Asia remains the principle long-term threat to the state security of China.’xl Even though China currently benefits from the stability created by the presence of the American Seventh Fleet, its strategists are deeply concerned that China remains vulnerable to ‘choking off’ by American vessels that patrol critical sea lanes such as the Malacca Straits. This is of profound concern to China given its dependence on resources and energy imports. For Beijing, this state of affairs gives Washington a ‘decisive veto’ over Chinese strategic ambitions.

For these reasons, several Chinese strategists even openly speak about working towards an explicit ‘division of influence’ between America and China in the region. For example, Shi Yinhong argues that America should accept Chinese dominance in East and Central Asia as well as naval dominance in the South China Sea while China would respect a dominant American presence to the east of Guam. A recent proposal by a Chinese naval officer to Admiral Tim Keating, the then head of the US Pacific Command Fleet, for the two nations to divide up the Pacific into strict spheres of influence was only half meant in jestxli because it would prevent Washington from ‘rejecting the peaceful ascension of China to global superpower.’xlii Although Beijing is not thinking in terms of an ‘inevitable’ war with America, it is relentlessly seeking to eventually alter the strategic and military status quo in Asia by weakening the American naval presence.

The broader point is that Beijing’s desires for eventual preponderance in Asia is diametrically at odds with Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s recent declaration that ‘the United States is not ceding the Asia-Pacific to anyone’—the latest reiteration of Washington’s position that has remain in force since the end of World War II.xliii

The false hope of political reform in China

There is a very close association between Beijing’s rise as a ‘responsible stakeholder’ within the US-led order and the emergence of a democratic China in Asia. After all, American ‘constructive engagement’xliv with China, which began under the Bill Clinton administration, was explicitly designed to hasten political reform in China; xlv the George W. Bush and Obama administrations have subsequently justified the continued economic and strategic engagement with China in similar terms.xlvi

Yet, according to this measurement, the framework is failing. Reassurances to Western leaders that China is gradually undertaking political reform xlvii is contradicted by both Beijing’s statements for its domestic audiencexlviii and by the consolidation and strengthening of the CCP’s power over the past decade.xlix In fact, it is important to realise that the ‘responsible stakeholder’ framework has weak support in Beijing and is distrusted precisely because the framework is viewed as an insidious one designed by Washington to undermine the CCP’s hold on power and predetermine China’s domestic endgame.l

The hope that by becoming more integrated into the existing economic and diplomatic order, China will take bigger steps towards political reform and democratisation is important to Washington for several reasons.

First, a more liberal and pluralistic Chinese political-society would improve the prospect of China becoming more receptive to regional and global norms. As recent issues such as Google’s battle with Chinese authorities over censorship and ongoing concerns with Chinese state-sponsored cyber-attacks on foreign firms demonstrate, differences over norms such as transparency, rule of law, and government restraint will continue to exacerbate tensions between China on the one hand and liberal-democratic systems on the other.

Second, Washington would feel much more comfortable if China developed a stronger regard for human rights, as has occurred in many countries throughout Asia. This would make issues such as Taiwan much less problematic since Washington would be more willing to eventually accept the reunification of Taiwan with China. A greater Chinese respect for human rights would also allay American concerns about the regime’s governance in areas such as Tibet and Xinjiang.

Third, the emergence of a liberal-democratic China would mean that the United States and regional countries will become more willing to accept Chinese political and strategic leadership in Asia as China’s economic power grows—China will have become ‘much more like us.’ In the longer term, it is arguable that Washington would be much more prepared to cede influence to a democratic China in Asia in a gradual and peaceful manner, just as Britain did for America in regions such as the Middle East and Southeast Asia throughout the previous century. This would be much more conducive to continued peace, stability and prosperity in the region than the scenario in which a rising China would remain an authoritarian state.

This liberal-democratic evolution certainly occurred in many East Asian countries such as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, but we should not ignore the historical context of these events. Countries such as Japan were losers in World War II whereas China was a notional winner. A defeated and devastated Japan had no choice but to accept the terms of the new dominant power in Asia in the form of the United States and take on board Washington’s expectations that Japan should eventually liberalise. Besides, Japan remained reliant on American might for its security needs after the war. Moreover, while previous authoritarian leaders and their human rights record in countries such as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan were routinely criticised by Washington, they knew that America would do little to seriously undermine the governments in these countries due to the exigencies of the Cold War. In contrast, the CCP—whose overwhelming priority is to remain in power—faces a contemporary ‘coalition of democratic states’ (America, Japan, South Korea, India, and Australia) pushing for political reform in China.

Therefore, far from welcoming integration into the US-led order, as the ‘responsible stakeholder’ framework implies, Beijing fears it. Even during the Bill Clinton years, senior People’s Liberation Army officers feared that Washington’s commitment to engagement was simply another way of subverting the CCP and perfecting the ‘soft containment’ of China.li Contemporary Chinese strategists observe that the post-Cold War ‘enemies of America’ are authoritarian states such as Iraq (under Saddam Hussein), Iran, Syria, Myanmar, and North Korea. Examination of strategic writings and political memos indicate that there is a (accurate) belief in China that Washington will seek to limit Chinese power and influence as long the country remains under the single-party rule of the CCP. For example, an article by influential Chinese scholar Yaqing Qin argues that ‘the theoretical problem’ of American foreign policy is the ‘hegemonic maintenance’ of a liberal order rather than mere survival of the state and maintaining a stable balance of power.lii According to Wang Jisi, arguably the best known contemporary Chinese strategist in America, there is a direct link between American hegemony and American liberalism. As Wang says, the idea that ‘American greatness depends on a world made safe for freedom’ is an ‘immutable tenet.’liii Consequently, Beijing remains convinced (probably correctly) that authoritarian states will forever remain ‘outsiders’ in any US-led order and agenda.

In addition to Beijing’s suspicion of the tacit motivations behind the ‘responsibility stakeholder’ framework, America’s attempts to ‘manage’ China’s rise and encourage domestic political reform is also hindered by the unexpected rise of the ‘corporate state’ that dominates China’s political-economy and places a disproportionate amount of resources in the hands of the state (enhancing the potency of China as a foreign policy actor).

Following the 1989 Tiananmen protests and the ‘Tiananmen Interlude’ (1989–92), the CCP has significantly restructured Chinese political-economy. Since the mid-1990s, ‘capitalism with Chinese characteristics’ has placed far more power and wealth in the hands of the state sector than in countries that followed ‘authoritarian capitalism,’ such as Japan and South Korea. Beijing is nurturing state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to dominate domestic markets and crowd out the private sector so that the CCP can retain its economic relevance, privileged status in Chinese society, and maintain control over the country’s increasing wealth. These SOEs historically receive over three-quarters of the country’s capital and over 90% all loans extended in 2009 by some estimates. This strategy has exacerbated serious societal problems such as corruption and inequality in China, and the so-called Beijing Consensus may yet fail. But for the moment, Beijing does not believe that sweeping economic—much less political—liberalisation is required for China’s continued rise.

Finally, this economic setup means that Beijing is less likely to be structurally committed to developing a domestic market dominated by private industry and governed by market processes and rule of law—historically, an essential step in the process towards political reform. Private corporations generally depend on open markets and rule of law in domestic and international environments within which to compete and thrive. In contrast, China’s SOEs ultimately succeed or wither away based on the privileges and protection extended to them by the CCP rather than allowing the free market to pick the winners and losers. In contrast to Washington’s vision of a free and open global economic system, Beijing’s inclination to view successful SOEs as instruments of state power and essential for regime security predisposes it to take a mercantilist rather than free-market view of global trade and commerce.

Accepting the reality of ‘strategic competition’

China is important to the United States because Washington has sensibly accepted the following three realities. First, few things in the world can be achieved without American involvement, but there are many things America cannot achieve by itself. Second, there are a growing number of regional and global problems that cannot be solved without Chinese cooperation. And third, America and China are finding themselves in an economic embrace that cannot be unwound without deleterious consequences for both countries. I would add a fourth reality that is not yet explicitly accepted in Washington policy circles: different material interests and political values prevent the existence of genuine US-China strategic cooperation—at least in the foreseeable future.

If acknowledged, the fourth reality demands that we move beyond a ‘responsible stakeholder’ framework that pursues strategic cooperation towards a policy framework that explicitly recognises strategic competition as a driving force behind bilateral relationship. Rather than attempting to manage China’s rise, perhaps the best we can hope to do is manage the consequences of China’s rise.

There have been serious tensions between the United States and China ever since Bill Clinton initiated the period of ‘constructive engagement’ in the 1990s. Many analysts correctly caution that the relationship with China will remain difficult, but periodic disagreement need not mean permanent ruptures in the relationship. Even so, it is important not to misinterpret China’s genuine desire for functional cooperation on a number of matters as an indication that Beijing desires deep strategic cooperation on issues such as climate change, non-proliferation (North Korea and Iran), and the regional strategic order in Asia. Chinese cooperation should not be mistaken for the fiction that China is eagerly embracing its role as a ‘responsible stakeholder’ in any US-led system, particularly in Asia. Instead, it is better for the Obama and subsequent administrations to recognise the inherent limitations of preventing deep strategic cooperation between the United States and China and work within this reality.

Recognising China as a ‘strategic competitor’ does not necessarily imply a deterioration in the current bilateral relationship, particularly the complicated economic relationship, which follows a somewhat separate logic of its own. Indeed, although China views America as its primary strategic competitor, it generally seeks tactical and diplomatic cooperation with Washington wherever possible without expecting strategic partnership as the next logical step. Were Washington to do the same, this would prevent it from offering political or strategic concessions to Beijing without receiving much (of strategic value) in return.liv

Nor does the reality of competition necessarily lead to conflict: explicitly recognising China as a ‘strategic competitor’ is not the same as treating Beijing as a ‘strategic adversary.’ On the contrary, as Elizabeth Economy and Adam Segal argue (in the context of calls to move towards a G2 approach, an argument that also applies to any framework creating heightened but false expectations), ‘elevating the bilateral relationship is more likely to lead to a quagmire, with recriminations flying back and forth, than to a successful partnership.’lv It is better to confront the reality of competition and create disincentives—such as a deepening of the economic relationship—for both sides to resort to force.

One can also persuasively argue that ignoring the reality of strategic competition as the driving force behind the bilateral relationship can lead to a dangerous incapacity to manage future tensions between the two countries. For example, the US-China Maritime Consultative Agreementlvi was signed in 1998 to herald a new era of bilateral engagement, especially with regard to confidence-building between the American and Chinese navies. Since then, despite a number of dialogues, military-to-military exchanges and countless Track 1.5 and Track 2 meetings, there have been no genuinely meaningful confidence-building measures to speak of, and the 1998 Agreement has lapsed into virtual irrelevance. In fact, there were more productive confidence-building initiatives, ‘hot-lines,’ military-to-military exchanges and agreement of protocols, and other frank discussions amongst senior officials from the United States and the Soviet Union in the 1970s and 1980s than there are between the United States and China today. The point is that explicit recognition of existing and future competition is more likely to give rise to genuine ‘competition management’ initiatives between the two countries.

Competing with an economic partner

Although competition means that the contest for influence is a zero-sum game, accepting the reality of competition does not always entail an unaffordable and unsustainable military build-up that would exacerbate the ‘security dilemma’ between the two countries and damage the critical economic partnership.lvii Instead, a better way forward would be to focus on driving competition to areas that maximise one’s leverage—playing to American strengths and Chinese weaknesses.

The purpose of this paper is not to suggest a comprehensive research agenda for a so-called ‘competitive strategies’ approach.lviii But it is worth noting that the first step of a realistic and prudent China-strategy would be to identify areas of leverage that can be used to redirect and redefine competition that will neither be destabilising or lead to conflict.

In this context, the Chinese economy is much less impressive and resilient than Westerners generally believe. Contrary to the general opinion in foreign policy circles, China has far fewer economic measures for retaliation than is widely feared—a good portent for continued economic cooperation between China and the United States. China still needs Western markets and consumers, technology, innovation, and know-how for its economic growth. The top Chinese SOEs are technically proficient but cannot yet match the innovation and creativity of Western competitors. Besides a thriving export sector heavily dependent on American and European consumers, Chinese economic growth is still dependent on a shaky banking system that lends enormous amounts of capital to inefficient SOEs to generate jobs and prevent large-scale social unrest.

Moreover, China has few options but to park the bulk of its foreign exchange reserves in America given the size of its reserves and the fact that the Central Bank of China needs to continually prop up the value of the American dollar (vis-à-vis the yuan) to support its domestic export industries, which generate the country’s best jobs. If there had been any other viable options besides purchasing American bonds, Beijing would have pursued these years ago. The fear that China has at its disposal economic WMDs that could wreck the American economy is unfounded. By giving the American economy a bloody nose or a black eye, the Chinese economy would lose its own head.

Strategically, China is arguably the loneliest rising power in history. It has no real reliable allies to speak of—not even Russia—and is distrusted by almost every state in Asia. It shares a border with 13 countries and is possibly genuinely trusted by only two—Myanmar and North Korea. Even with respect to political values, key Asian states join America in remaining disapproving of China’s authoritarian system, including Japan, South Korea, India, and increasingly Indonesia.

In contrast, American strategic leadership and values are widely accepted even if Washington’s policies periodically draw intense criticism. China therefore profoundly fears isolation and since the early 1990s, its foreign policy has been designed primarily to avert confrontation with America, avoid strategic seclusion, and alleviate regional fears about its rise. China is big enough to be a ‘spoiler’ but also rarely capable of exercising leadership. Instead, it relies on offering foreign governments economic favours to gain international support.

This provides America with a strong case to downplay the importance of Chinese acquiescence in its search for a grand Asian strategy. Instead, Washington needs to secure common ground with and cooperation from other key states on an issue-by-issue basis before seeking Chinese cooperation. This was the spirit behind Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s recent appeal for America to ‘step up relations with Japan, India and Southeast Asia’ and to be ‘less preoccupied with China’—a sentiment that is mirrored throughout almost all of Asia.lix

The successful US initiative to grant India a special waiver from the Nuclear Suppliers Group in 2008 illustrates the effectiveness of initially ‘ignoring,’ then ‘isolating,’ before ‘pressuring’ China—after securing agreement from other players. Despite the intense China-India strategic rivalry, Beijing ultimately put aside its objections to the deal and abstained in the final vote as it did not want to appear isolated on the issue. Even in situations where this tactic might be inappropriate, it prevents offering unilateral concessions to a strategic competitor rather than genuine partners.

It is not in America’s or its allies’ interest to ‘contain China’s economic rise.’ However, the need to explicitly ‘compete’ is as important as continuing to seek tactical cooperation on issues. If Beijing continues to extend its influence in the region at the expense of Washington, smaller Asian states are much more likely to ‘hedge’ by increasingly band-wagoning with China since they would have few alternatives.

Finally, as Daniel Twining argues, there is a strong economic and strategic logic for America facilitating ‘the ascent of friendly Asian centres of power that will both constrain any Chinese bid for hegemony and allow the United States to retain it position as Asia’s decisive strategic actor.’lx The two most important countries here are Japan and India whose interests are remarkably aligned with that of the United States. Indonesia is a third country that will be increasingly important. The priority here is not to dictate policy to these countries but to ensure that both command sufficient independent strategic and military weight to ‘restrain’ Chinese strategic objectives into the future. This will help perpetuate a long-standing objective in American foreign policy first articulated by Averell Harriman to the House Committee on Foreign Affairs in 1947: ‘a balance of power preponderantly in favour of the free countries.’

Conclusion

Given the US-China economic relationship and China’s importance in Asia, America’s temptation is to seek a comprehensive cooperative framework to perpetuate its leadership and tame a rising China in order to promote stability in the region. Increasing economic interdependence does create common interests, and structured dialogues can reduce misunderstanding. But as Asia’s preeminent power and civilisation for all but 200 of the past 3,000 years, China is too big, proud, and independently minded for America to ‘tame’ or ‘manage.’ Washington cannot hope to decisively determine the endgame for an authoritarian China—that the CCP leading a country of 1.4 billion people will choose to become a ‘responsible stakeholder’ within a US-led order. Instead, America (and allies such as Australia) needs to confront the reality that the CCP’s two primary objectives—overseeing China’s re-emergence as the dominant power in Asia and retaining its exclusive hold on political power—are fundamentally incompatible with Washington’s vision for Asia and hopes for China.

Strategic competition—especially in an era of a rising great power—is a well-established reality for international relations theory and history. US foreign policy and interaction with Beijing must be based on accepting the reality that ‘strategic competition’ between the United States and China is real, already occurring, and likely to continue into the foreseeable future. It is an honest acknowledgement of a contest taking place over not just the accumulation of material power and influence but also a competition to determine the shape of the region. If America is to retain its leadership in the Asia-Pacific and promote continued peace, as presidents since Harry Truman have promised to do, then Washington needs to help strengthen the incentives for peace (i.e. promote China’s economic interaction with the world) and simultaneously develop a strategic framework for competing effectively with China—especially in Asia. In his remarks at the 2009 US-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue, President Obama argued that ‘the pursuit of power amongst nations must no longer be seen as a zero-sum game.’lxi Unfortunately, reality dictates otherwise. Assuming that strategic competition is taking place is far more preferable and prudent than relying on a failing ‘strategic stakeholder’ framework, let alone the dangerous fantasy of a G2.

Finally, the fact that the Chinese economy is intimately intertwined with the American and global economies is also a powerful factor behind important tactical cooperation on many issues. Combined with the nuclear capabilities of both countries, which is the basis for a relatively stable ‘balance of terror,’ there is every chance that the contest for influence can remain bounded, manageable and ultimately peaceful.

Dr. John Lee is the Foreign Policy Fellow at the Centre for Independent Studies in Sydney and a Visiting Fellow at the Hudson Institute in Washington, D.C. He is the author of Will China Fail?