The Shadow Pandemic: Three reforms for the post-pandemic mental healthcare system

Executive Summary

Living through the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in increased mental distress and ill-health among broad population groups globally. These challenges are likely to be enduring and have serious implications — not only for affected individuals and their families, but for all facets of society, the health sector, and the wider economy.

Australian governments at both federal and state level are cognisant of the magnitude of the problem and the necessity to include mental health in pandemic recovery planning. They have already committed significant funding and resources to managing this situation. However, there are critical operational gaps that must be addressed to ensure any strategy is comprehensive, long-term, and forward-thinking. (While there may be funding shortfalls, it is outside the scope of this paper to address the adequacy of current spending.)

This paper examines three high-value and critical gaps:

- The decades-old problem of existing reform recommendations that have been repeatedly neglected by successive governments

- The national shortage of mental health professionals (insufficient workforce capacity).

- The generation born during the pandemic and undergoing their formative years who have experienced unprecedented impediments to normative bonding, development, and socialisation due to COVID-19 mitigation strategies such as face masks, lockdowns, and social distancing.

This paper offers the following recommendations to address these issues:

- Instigate a whole-of-government freeze on further mental health reviews, inquiries, and analyses until all recommendations from prior reviews are considered and either implemented or rejected with appropriate explanation.

- Expand the allied health services list allowed for Medicare Focussed Psychological Services rebates to include suitably qualified and registered counsellors, psychotherapists, and mental health nurses.

- Develop a national research model to study the long-term effects on children born during the pandemic to assess the scope of attachment insecurity, socialisation issues and emotional and neurodevelopmental issues.

It is critical that policymakers address these issues when considering mental health service reforms to:

- Alleviate further waste of time and resources;

- Ensure critical service provision gaps are filled; and

- Monitor and support a large cohort of children who may potentially experience crippling mental health and social problems, leading to a reduced quality of life.

Introduction

Snapshot of the current mental health landscape in Australia

The COVID-19 pandemic of 2020-2022 has had far reaching consequences across the globe, not least being a substantial increase in mental health issues across diverse population groups. This rise has been so dramatic that the crisis has been labelled a ‘shadow pandemic.’ 1

The pandemic has also highlighted and exacerbated Australian mental healthcare system shortcomings that are longstanding, previously and repeatedly identified, and entrenched.2

There have been numerous pandemic-related stressors that have taken a toll on our collective psyche:

- The possibility of severe acute illness and subsequent chronic illness through post viral sequelae;

- Deaths across a wide demographic range, including the young;

- Daily media images of mass graves and ICU patients struggling to breathe, repeated through the 24-hour news and social media cycles;

- Critical and unexpected supply shortages;

- Mass job losses;

- Economic uncertainty and economic scarring;3

- Lockdowns and curtailed personal liberties;

- Civil unrest and violent demonstrations;

- Extended periods of isolation and attendant loneliness;

- Public health mandates;

- Increased incidence of domestic violence ;4 and

- Profound changes to work and schooling routines.

These experiences added cumulatively to the distress of recent natural disasters such as severe drought, rodent plagues, catastrophic bushfires, and flooding; as did geopolitical instability including Chinese ‘wolf warrior diplomacy’5 unsettling the Asia-Pacific region, and the war in Ukraine.

Compounding these factors is the deeper societal phenomenon of increasing use of — and dependence on — smart devices and social media. These technologies are designed specifically to manipulate and capture attention, with the consequence of reducing in-person human connection and leading to rising rates of tech-addiction, dysfunctional focus, cyber-bullying, anxiety, and depression.6 In Stolen Focus: Why You Can’t Pay Attention, author Johann Hari discusses how managing life during the pandemic has fast-tracked our increasing reliance on smart phones, the Internet, and screens in general. He quotes political writer Naomi Klein: “We were on a gradual slide into a world in which every one of our relationships was mediated by platforms and screens, and because of Covid, that gradual process went into hyper-speed.” 7

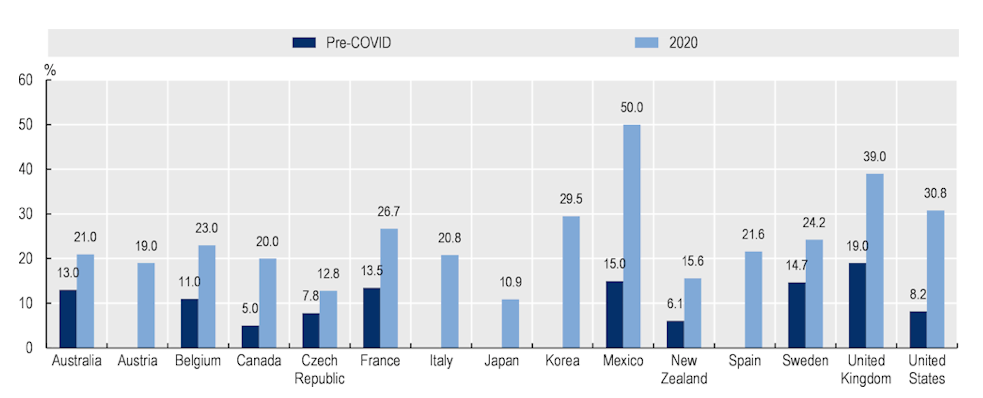

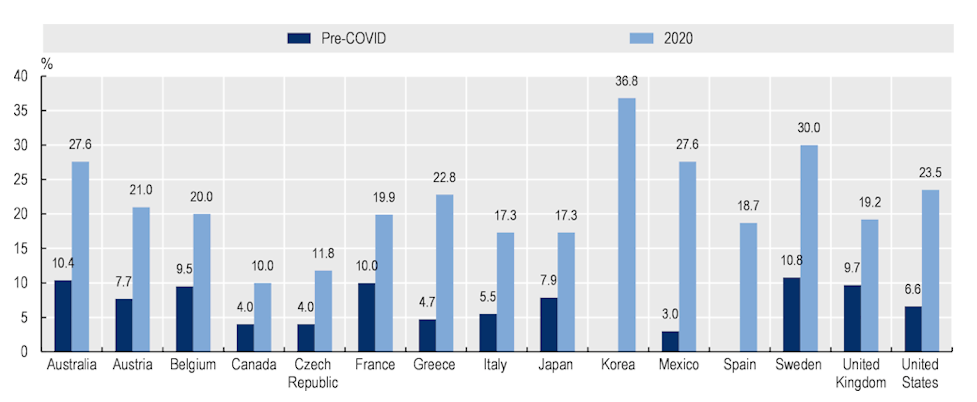

This ‘perfect storm’ of intersecting conditions has resulted in a surge in mental ill-health and distress. In a March 2022 report on early evidence of the pandemic’s mental health impacts globally, the World Health Organization (WHO) quoted the Global Burden of Disease 2020 study estimates of a 27.6% increase in the prevalence of major depressive disorder, and a 25.6% rise in anxiety worldwide.8

Figure 1. Prevalence of anxiety increased significantly in 2020

OECD National estimates of prevalence of anxiety or symptoms of anxiety in early 2020 and in a year prior to 2020

Note: To the extent possible, 2020 prevalence estimates were taken from March-April 2020

Source: OECD, 2022, May 129

Figure 2. Prevalence of anxiety increased significantly in 2020

OECD National estimates of prevalence of anxiety or symptoms of anxiety in early 2020 and in a year prior to 2020

Note: To the extent possible, 2020 prevalence estimates were taken from March-April 2020

Source: OECD, 2022, May 129

Australia’s mental health trends paint a similar picture, but of general note is that both our pandemic and pre-pandemic rates of depression are higher than most other OECD countries, with the exception of Sweden and Korea.9

In September 2021, the Business Council of Australia documented widespread concern about the nation’s mental health during the pandemic in an open letter from the Australian business community. This was signed by 88 industry leaders from companies employing a combined total of over one million people: “…we can also see the impact of lockdowns on our people, on our customers, on our small business suppliers, and on communities and families right across the country. Australia is juggling a mental health emergency at the same time as a global pandemic.” 10

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) reports that in the month prior to 9 January 2022, calls to mental health and suicide helplines rose from levels seen in the preceding two years of the pandemic. Lifeline received 89,679 calls in this period, 6.5% and 16% higher than the same period 12 months and 24 months earlier, respectively. Kids Helpline received 22,935 calls for this period, which was a 1.8% increase over the same period 12 months previously and a 0.4% increase from 24 months previously. Beyond Blue took 21,425 calls during this period, which represented a 26.7% increase from the same period 24 months previously but a decrease of 5.7% from the same period 12 months prior. 11

One positive aspect to note is that despite predictions of the pandemic leading to a sharp rise in suicides, recently released data shows that in Australia this is currently not the case, despite the increase in psychological distress and primary risk factors. (This should not provide an excuse for complacency or redirected funding; rather, it offers hope in a bleak landscape.)

Current mental health spending in Australia

McGorry asserts that: “Mental illness is the non-communicable disease (NCD) with the most potent social and economic consequences and is a major source of disease burden alongside cancers and cardiovascular disease. Yet it attracts a mere 2 per cent of health spending worldwide.” 13

However, AIHW data reveals that Australia spent 7.6% of its health budget on mental health services for the 2019-2020 period. This equates to a per annum, per person spend of $431, or $11 billion nationally. While this paper will not analyse whether current total spending is adequate or inadequate, it should be noted that of this $11 billion, only $1.4 billion was spent on Medicare-subsidised mental health rebates. Such rebates were received by 10.7% of the population, meaning only 2.7 million Australians received benefits.14 If, as mentioned above, approximately 25% of Australians are currently experiencing mental health issues, then subsidised mental healthcare provision and access is falling short.

The ‘missing middle’ is a widely accepted term for mental healthcare provision deemed to be lacking for moderate cases of mental ill-health, although there is not consistency across the board with this view. 15 16 1 Youth-specific mental health research organisation Orygen reports that 4.6% of the general population who have moderate mental health issues are not receiving adequate or sufficient mental healthcare: “…1.2 million Australians with moderate mental ill-health are largely underserved by both Medicare-subsidised mental health supports and may require secondary or tertiary care.” 17 To supply mental healthcare provision for this under-served health demographic, Medicare rebate provider classifications must be expanded, which will subsequently increase capacity. The needs of the ‘missing middle’ cohort require more sustained and higher-level support than crisis lines or online self-help programs can provide.

Despite high levels of spending on health services, it is estimated that over $12 billion annually is lost in productivity due to mental ill health and suicide in Australia. The Productivity Commission estimates that costs blow out to between $200-$220 billion per year when accounting for direct costs such as service provision, carer support, housing, and related justice services. A 2014 PwC analysis determined a return on investment of $2.31 for every dollar spent on successful implementation of mental health services.18 Aside from the moral imperative, addressing mental ill-health clearly has a compelling economic rationale.

While it is outside the scope of this briefing to address all gaps in mental health service provision, this paper aims to articulate three critically unaddressed areas of concern in Australia post-pandemic, and offer policy solutions for reform. These proposals offer the potential for high-value, high-impact gains. One is promptly achievable; the remaining two require more intensive consideration and long-term effort.

Firstly, it is important to ensure that current and recent recommendations for reform are not simply filed away but acted upon. Over the past three decades, numerous inquiries, analyses and recommendations have been ignored or neglected.

Secondly, it is imperative to remedy shortfalls in accessible and affordable mental health workforce numbers by utilising existing professionals through expansion of the allied health list, which determines rebates for Focussed Psychological Strategies (FPS) through the Medicare Better Access Initiative.

Thirdly, the COVID-19 safety precautions of face masks, lockdowns and social distancing, in addition to increased parental distress, have potentially caused novel, large-scale disruption to normative infant development, socialisation, and attachment. This will require ongoing study and monitoring to assess the frequency, severity and manifestation of possible insecure attachment in order to develop suitable interventions if required.

The importance of consensus in defining mental health

The WHO defines mental health as,

“… a state of well-being in which an individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and is able to make a contribution to his or her community.”

“Mental health is fundamental to our collective and individual ability as humans to think, emote, interact with each other, earn a living and enjoy life. On this basis, the promotion, protection and restoration of mental health can be regarded as a vital concern of individuals, communities and societies throughout the world” (WHO, 2018).

Importantly, the WHO recognises that general health is “…a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” The critical points in relation to understanding mental health are that it is not “merely the absence” of dysfunction, disease or distress, nor is it distinct from overall health. 20

Cartesian dualism — which argues a separation of mind and body, and characterises modern Western medicine — offers a segmented, often reductionist, perspective on human health and enforces an artificial division between physical and mental well-being. It is essential for destigmatisation efforts and the development of more effective support that mental health is understood holistically and not as a separate part of human health but as indivisible from the general health of all. 21 1

GAP ONE

Past and current investigations into mental healthcare reform and the ‘Groundhog Day’ problem

Managing and mitigating mental ill-health and distress has always been an overwhelming and fundamentally ‘wicked problem;’ complex, entrenched, multi-faceted, and intersecting.22 The pandemic, coinciding with extreme climate events and geopolitical instability, has upgraded the task from Herculean to Sisyphean.

This may explain why there has been more strategising and scholarship than substantive reform to date in Australia. In their paper responding to the most recent Productivity Commission’s Inquiry report, Duckett and Swerissen refer to a deluge of strategies over the years producing “positive rhetoric” and awareness that reform is needed, but with little actual improvement. 23 Over the past 30 years, Australia has had multiple mental health inquiries and subsequent recommendations, many offering the same conclusions and reform suggestions.2 The situation has descended into a ‘Groundhog Day’ of repetition and duplication.24

In June 2020, six months into the pandemic, the Productivity Commission handed down an extensive three-volume report on mental health to the government, completing one of the largest inquiries in the Commission’s history (the Inquiry). The process took 18 months and resulted in more than 1200 pages of discussion and recommendations; much of which related to the existing pre-pandemic state of mental health in Australia.18

In response, the government engaged the National Mental Health Commission (NMHC) — an executive agency established in 2012 to provide independent policy advice — to develop a comprehensive strategy for addressing the many issues raised by the Inquiry. The response was released in March 2022 and is called Vision 2030: Blueprint for Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. A critical implementation document that then Health Minister the Hon Greg Hunt MP said “… will articulate the policy requirements, system architecture, funding mechanisms and service design and outcomes necessary to implement Vision 2030”25 is also expected but at the time of writing was not completed and did not have an expected release date.26

Without this implementation roadmap, Vision 2030 is not a blueprint but a mission statement, albeit an admirable one. The steps to implementation and actionable strategy are imperative to bring this vision to fruition and the NMHC should advise an expected date of release as a priority.

(The NMHC also articulates the need for long-term mental health support post-pandemic in its National Mental Health and Wellbeing Pandemic Response Plan, which was released in May 2020 and builds on an earlier report, the National Mental Health and Wellbeing Disaster Framework.)

The 2021 Federal Budget corralled $2.3 billion for investment in general mental health services and pandemic-response spending,27 with individual states and territories formulating their own specific responses. Of note is the $3.8 billion committed in the Victoria State Budget, reflecting recognition of the toll extended lockdowns took on Victorians and a higher commitment to addressing mental health generally. Mental Health Australia’s analysis of the Federal Budget notes: “There are few, if any, areas of government activity more formally examined than mental health services and suicide prevention” and commends the $7.3 million directed to the NMHC “…to lead new efforts in accountability.”28

Recommendation One: That no further investigations be conducted into the Australian mental health system until all prior recommendations over the past decade have been reviewed and either implemented or formally dismissed with a rationale against implementation.

GAP TWO

Workforce Capacity

In 2011, the National Mental Health Workforce Advisory Committee published a National Mental Health Workforce Strategy that was endorsed and authorised by the Australian Health Ministers’ Conference. This document articulated the growing need for an increase in the mental health workforce capacity to support then-current and future needs.29

However, in the decade since this strategy was released, little progress has been made in expanding capacity, with the pandemic resulting in an already overstretched workforce being further overwhelmed. By 2018, the government had committed to the development of another similar workforce strategy — a 10-year plan with the same title as the 2011 plan.30

Another set of recommendations, this time called the Draft National Mental Health Workforce Strategy Background Paper (the Strategy), subsequently prepared in 2021 by private advisory firm ACIL Allen, reveals a lack of consistency and adequacy in data collection across the various professions due to diversity of occupation, lack of standardisation and varying reporting requirements.30 More rigorous and extensive data collection across the mental health professions is needed to gain an exact picture of workforce shortages in this sector.

The overall mental health workforce includes a diversity of professions, notably psychiatrists, psychologists, counsellors and psychotherapists, mental health nurses and nurse practitioners, social workers, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health Workers, general practitioners (GPs), occupational therapists, lived experience peer workers and dieticians. However, only services provided by GPs, psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers, and occupational therapists are Medicare-subsidised.31

Excluding other counselling professionals is effectively anti-competitive and reduces the available support capacity, particularly in country and outlying areas, since the psychology profession distribution is predominantly based in urban areas. Recent AIHW data shows that roughly 90% of psychiatrists and 80% of psychologists are based in major cities.32 Conversely, the Australian Counselling Association (ACA) cites studies by Pelling (2005), Vines (2011), and Schofield & Roedel (2012) examining counselling profession distribution, with roughly 33% of counsellors working in regional, rural, and remote areas. Duckett and Swerissen note that, “People in the cities get more services than people in the country.”23

The Strategy reports a current national requirement of 74,252 fulltime equivalent (FTE) mental health workers, with only an estimated 50,518 workers currently available, and demand expected to grow by 2030 to reach an estimated requirement of 87,645 FTE workers.30

This capacity shortage could be readily addressed by expanding the Medicare Better Access Initiative rebate scheme to include existing registered and suitably qualified counsellors and psychotherapists, as strongly advocated by the ACA,33 the Psychotherapy and Counselling Federation of Australia (PACFA),34 and Tasmanian Senator Jacqui Lambie.35 Extending the rebate to practitioners who meet peak body quality standards would provide better access to the Better Access scheme.

Importantly, since counselling is currently an unregulated profession in Australia, both counselling peak bodies support only the inclusion of counsellors who are registered with either the ACA or PACFA, and who are degree-qualified or above (holding at minimum an Australian Qualifications Framework Level 7 qualification) with a minimum of two years practice and 750 client contact hours.33 34

The AIHW states that for the 2.7 million people (or 10.7% of the Australian population) to access Medicare-subsidised mental health services in the 2019-20 period, 45.3% of those services were provided by psychologists.36 The Australian Psychological Society conducted a survey in January and February of 2022, polling 1456 psychologists across the country. The results showed that one in three psychologists have closed their books to new clients, an increase from one in five in 2021. This contrasts starkly with pre-pandemic availability when only one in 100 psychologists had no capacity for new clients.37 Wait-times are now extensive with clients waiting 3–6 months before initial appointments are available, further entrenching psychological difficulties for those forced to wait for care.38

The current Medicare subsidy scheme has the effect of tunnelling mental health clients to a limited range of already over-burdened services, while reducing potential business for a qualified workforce ready and eager to accept new clients. Both the ACA and PACFA report that approximately a third of their members desire and — importantly — have capacity for additional clients.33 34

Counsellors and psychotherapists are currently under-utilised in the Australian mental healthcare system, but are well-equipped to manage mild to moderate mental health issues, as well as trauma and addiction.34 Those with advanced training may also work with issues at the more severe end of the scale. PACFA reports that 67% of the counselling workforce have post-graduate qualifications, with 34% holding registration for a decade or longer.34

While unable to diagnose or prescribe medication, counsellors and psychotherapists offer an effective, valuable, empathetic, and person-centred service that is well received by clients.34 Recent studies have also (somewhat controversially) shown there are fewer complaints lodged against counsellors than psychologists, and that client satisfaction with the therapeutic relationship is higher with counsellors than psychologists in measures of rapport, understanding and assistance.*25 26

An argument against the inclusion of counsellors and psychotherapists in the Better Access Initiative might be that the profession is not regulated by the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) and governed instead by independent peak bodies. However, this argument holds no weight given the social work profession, which is included under the Medicare rebates scheme for FPS provision, is similarly self-regulating through the Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW) and holds no regulatory connection with AHPRA.30

It should be noted that the two peak bodies representing the counselling profession in Australia — PACFA and the ACA — endorse a robust ethical and professional framework and stipulate continuing education and professional supervision requirements to which members must adhere. Further adding to its credentials, the ACA now also holds Observer membership “…of the WHO’s Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Reference Group for Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) in Emergency Settings.”33

It should also be noted that GPs previously referred patients to counsellors prior to 2006, when introduction of the Better Access Initiative excluded the counselling profession from rebate eligibility.33

Expanding the allied health professions list eligible to FPS in the Medicare Better Access Initiative offers a timely and practical solution to address workforce shortfalls. Credentialed mental health nurses should also be included as an addition to this Medicare rebate list. The Australian College of Mental Health Nurses shares similar views to the ACA and PACFA in bewildered exasperation at being excluded from providing critical support to an over-stretched service when their members have the both the skills and capacity to offer immediate support.41 Mental health professor John Hurley believes that the current skewing of rebates to the psychology profession unnecessarily bypasses trained and competent mental healthcare professionals in favour of one discipline. In 2021, clinical psychologists drew 34.3% of Better Access benefits paid, with non-clinical psychologists at 27.9% and GPs at 28.2%. 27

However, GPs are also stretched, with an average consultation time of just under 15 minutes per person; enough time for pharmacological support but insufficient for effective talk-based modalities. Yet psychological concerns are the main issue patients visit their GP to discuss, making up 65% of visits between 2017-2019.33

Increasing workforce capacity will also provide additional support for the under-served ‘missing middle’ cohort who require more in-depth and longer-term support than is currently available. As mentioned above, it will also improve face-to-face service provision and access for regional, rural and (to a lesser extent) remote populations.

In short, there is no valid reason for excluding counsellors, psychotherapists or mental health nurses from the Better Access Initiative; and many compelling reasons for their prompt inclusion.

Recommendation Two: Government should conduct a cost-benefit analysis of expanding the list of allied health professions accepted by the Medicare Better Access Initiative to offer rebate-eligible FPS, specifically to include suitably qualified and registered counsellors, psychotherapists, and mental health nurses.

*Note: The author references this as an endorsement of the counselling profession and not an indictment of the psychology profession.

GAP THREE

Potential and novel attachment disruption in infants and toddlers due to COVID-19 mitigation mandates

Attachment theory — the widely-accepted school of thought in biopsychosocial development — states that the quality and consistency of early infant and toddler bonding to their primary caregiver/s is pivotal to healthy development and milestone achievement.29 It is believed that insecure attachment leads to psychopathologies; socialisation issues; emotional dysregulation; relationship difficulties; learning and employment disruption and reduced outcomes; chronic health issues; higher rates of addiction; reduced empathy and compassion; increased xenophobia and racial prejudice; and delinquency and criminality. 30

Harvard University’s Center on the Developing Child (the Center) says: “Developmental timing is critical. Science tells us that experiences and exposures during pregnancy and the first few years after birth affect developing biological systems in many ways that are difficult to change later. For example, if a woman experiences excessive stress, poor nutrition, or toxic environmental exposures during pregnancy, it can affect how organs, stress response, and metabolic systems develop, with long-lasting impacts into adulthood, such as increased risk for heart disease, obesity, diabetes, and mental health conditions.”31

Green et al write in a 2020 article in the Journal of Neonatal Nursing that recent studies using magnetic resonance imaging “…suggest that the relationship between brain development and maternal interactions is sensitive as early as the postnatal period…” and that “Mask-wearing during this sensitive period then raises questions regarding mother-infant interactions and whether this could negatively impact on brain connectivity and growth” as well as normal mother-infant bonding.

Similarly, the United Nations notes that: “Effects of COVID_19 on the brain are of concern. Neurological manifestations have been noted in numerous countries in people with COVID-19. Moreover, the social consequences of the pandemic may affect brain health development in young children and adolescents (emphasis added) and cognitive decline in the older population.”33

Given that the pandemic has involved an unprecedented reduction in access to facial stimulus and social interaction through face-coverings, social distancing, and lockdowns, it is feasible to assume probable attachment disruption; the question is how extensive and detrimental this will be. Limited research has been conducted to date, but based on current understanding of attachment theory, the issue presents a potentially grave and large-scale challenge for society and policymakers in the years to come.

In 2020, there were 294,369 registered births in Australia, and, based on the declining birth rate, a slightly lesser number is anticipated for 2021 figures, which at the time of writing had not been released. This gives an estimate of more than 550,000 infants born during the two critical pandemic years (March 2020 – March 2022) who may have, and may continue to experience, impeded neurodevelopment and bonding with subsequent disordered attachment.33

It should be noted that pandemic-related attachment issues in adolescents and adults are also currently being seen and are further anticipated. These relate to pre-existing insecure attachment, with COVID-19 issues triggering an exacerbation of attachment-related anxiety and related behavioural responses. Numerous scholarly works discussing and researching this issue already exist, yet there is a dearth of research or attention being directed to developing infant attachment.

Recommendation Three: Pre-emptive long-term research into the implications and potential ramifications of facial coverings, social distancing and lockdowns in cognitive, emotional, and social development and attachment in infants and toddlers should be commenced as a matter of urgency. A generational study of Australian infants born during the pandemic should determine and track attachment and neurodevelopmental issues and potential psychopathologies. This project should also determine, if required, appropriate life-span psychological support to manage the mental health and normative development of this cohort to circumvent and alleviate future large-scale mental ill-health and relational, education, employment, and quality-of-life issues.

Conclusion

The Australian mental healthcare system is an overly complicated tangle of strategies and reforms further complicated by the federal system. Duplication abounds and the system has been referred to as an “incoherent jumble.”23 This must be addressed and simplified through a whole-of-government approach if Vision 2030 is to succeed.

A ready-made solution may exist to address workforce shortages, regional, rural, and remote accessibility to mental health care professionals, and provide additional support for those with moderate conditions who require more sustained support than lower-level care. A cost-benefit analysis should explore including counsellors, psychotherapists, and mental health nurses for support provision within the Medicare Better Access Initiative framework.

Finally, to mitigate potential long-term and widespread developmental and attachment issues in over half a million infants who were born during the pandemic, extensive studies should be designed and conducted to monitor this situation and measures developed to offer prompt and sustained support where needed.

Endnotes

- McGorry, Patrick. (2021). Finding the ‘missing middle’: Those who have fallen through the mental health care cracks. Retrieved from https://orygen.org.au/About/News-And-Events/2021/Finding-the-%E2%80%98missing-middle%E2%80%99-those-who-have-fallen (Accessed April 2022).

- Whiteford, Harvey. A & Buckingham, William J. (2005). Ten years of mental health service in Australia: Are we getting it right? The Medical Journal of Australia, 182(8). Retrieved from https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2005/182/8/ten-years-mental-health-service-reform-australia-are-we-getting-it-right (Accessed April 2022). p.396

- Irons, John. (200(). Economic scarring: The long-term consequences of recession. Economic Policy Institute Briefing Paper #243. Retrieved from https://www.epi.org/publication/bp243/ (Accessed 8 May 2022). pp.1-2

- Boxall, Hayley., Morgan, Anthony & Brown, Rick. (2020, July). The prevalence of domestic violence among women during COVID-19 pandemic. Australian Government: Australian Institute of Criminology Statistical Bulletin 28, p.12. Retrieved from https://www.aic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-07/sb28_prevalence_of_domestic_violence_among_women_during_covid-19_pandemic.pdf (Accessed 22 June 2022).

- The National Bureau of Asian Research. Understanding Chinese “Wolf Warrior Diplomacy.” Retrieved from https://www.nbr.org/publication/understanding-chinese-wolf-warrior-diplomacy/ (Accessed 26 May 2022).

- Hari, Johann. (2018). Lost Connections: Uncovering the Real Causes of Depression and the Unexpected Solutions. Bloomsbury Circus, UK. pp. 85-90

- Hari, Johann. (2022). Stolen Focus: Why You Can’t Pay Attention. Bloomsbury Publishing, UK. pp. 137-148, pp. 266-268.

- World Health Organization. (2022, March 2). Mental Health and COVID-19: Early evidence of the pandemic’s impact. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Sci_Brief-Mental_health-2022.1 (Accessed March 2022).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2021, 12 May). OECD Policy responses to Coronavirus (COVID_19): Tackling the mental health impact of the COVID-19 crisis: An integrated, whole-of-society response. Retrieved from

- https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/tackling-the-mental-health-impact-of-the-covid-19-crisis-an-integrated-whole-of-society-response-0ccafa0b/ (Accessed 28 May 2022).

- Business Council of Australia. (1 September 2021). An open letter from the business community. Retrieved from https://www.bca.com.au/an_open_letter_from_the_business_community (Accessed 8 May 2022).

- Australian Government: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2022, May 17). Mental health impact of COVID-19. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mental-health-services/mental-health-services-in-australia/report-contents/mental-health-impact-of-covid-19 (Accessed 31 May 2022).

- Australian Government: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2020, April 20). The use of mental health services, psychological distress, loneliness, suicide, ambulance attendances and COVID-19. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/suicide-self-harm-monitoring/data/covid-19 (Accessed 19 May 2020).

- McGorry, Patrick. (2021). An inclusive blueprint for mental health: Lifting the iron curtain around care. Griffith Review 72: States of Mind. Griffith University.

- Australian Government: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2022). Mental health services in Australia: Expenditure of mental health-related services. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mental-health-services/mental-health-services-in-australia/report-contents/expenditure-on-mental-health-related-services (Accessed April 2022).

- Looi, Jeffrey C.L., Kisley, Stephen, R., Allison, Stephen & Bastiampillai, Tarun. (2021, 1 December). Is there a missing-middle in Australian healthcare? Australasian Psychiatry. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/10398562211057069 (Accessed 7 May 2022).

- Kaine, Christine & Lawn, Sharon. (2021) The ‘Missing Middle’ Lived Experience Perspectives. Lived Experience Australia Ltd. South Australia. Retrieved from https://www.livedexperienceaustralia.com.au/research-missingmiddle (Accessed 9 May 2022).

- Orygen. (n.d.). Defining the missing middle.https://www.orygen.org.au/Orygen-Institute/Policy-Areas/Government-policy-service-delivery-and-workforce/Service-delivery/Defining-the-missing-middle/orygen-defining-the-missing-middle-pdf?ext (Accessed 6 June 2022).

- King, Stephen. A Brief Overview of the Mental Health Inquiry. [Speech]. Australian Government: Productivity Commission. Retrieved from https://www.pc.gov.au/news-media/speeches/mental-health (Accessed May 2022).

- Pricewaterhouse Coopers. (2014). Creating a mentally healthy workplace: Return on investment analysis. Retrieved from https://www.pwc.com.au/publications/pdf/beyondblue-workplace-roi-may14.pdf (Accessed 8 May 2022). p. iv.

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). Constitution. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/about/governance/constitution#:~:text=Constitution%20of%20the%20World%20Health%20Organization&text=Health%20is%20a%20state%20of,absence%20of%20disease%20or%20infirmity (Accessed March 2022).

- Gendle, Matthew. H. (2016). The Problem of Dualism in Modern Western Medicine. Mens Sana Monograph. 14(1), pp141-151. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5179613/ (Accessed March 2022).

- Hannigan, Ben, & Coffey, Michael. (2011). Where the wicked problems are: The case of mental health. Health Policy, 101(3), pp.220-227. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0168851010003325. (Accessed May 2022).

- Duckett, Stephen & Swerissen, Hal. (2020). A redesign option for mental health care: Submission to Productivity Commission review of mental health. Retrieved from https://grattan.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Grattan-Inst-sub-mental-health.pdf (Accessed 16 May 2022).

- Griffiths, Cathleen, M., Mendoza, John., & Carron-Arthur, Bradley. Whereto for mental health reform in Australia: Is anyone listening to our independent auditors? (2015). The Medical Journal of Australia, 202(4), p. 172-174. Retrieved from https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2015/202/4/whereto-mental-health-reform-australia-anyone-listening-our-independent-auditors (Accessed 30 May 2022).

- Hunt, Greg. (2020, June 5). Official correspondence, Minister for Health to Christine Morgan, CEO, National Mental Health Commission. Retrieved from https://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/getmedia/ede9e4e7-d626-4721-848a-f2944b47ea3c/National-Mental-Health-Commission-Statement-of-Expectations (Accessed 19 May 2022).

- Australian Government: National Mental Health Commission, (2022, May 18.) Email, administrative support to Meegan Cornforth, Torrens University student.

- Australian Government: National Mental Health Commission. 2021-2022 Federal Budget. Retrieved from https://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/news-and-media/mental-health-awareness-programs/2021-federal-budget (Accessed March 2022).

- Mental Health Australia. (2021, May 28). 2021 Federal Budget Analysis. Retrieved from https://mhaustralia.org/sites/default/files/docs/mental_health_australia_2021_federal_budget_analysis.pdf.pdf (Accessed May 2022).

- Australian Government: Mental Health Workforce Advisory Committee. (2011). National Mental Health Workforce Strategy. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/f7a2eaf1-1e9e-43f8-8f03-b705ce38f272/National-mental-health-workforce-strategy-2011.pdf.aspx (Accessed 19 & 20 May 2022).

- Australian Government: Mental Health Workforce Strategy Taskforce. (Document drafted by ACIL Allen) (2021, August). Draft National Mental Health Workforce Strategy Background Paper. Retrieved from https://acilallen.com.au/uploads/media/NMHWS-BackgroundPaper-040821-1628485846.pdf (Accessed 20 May 2022). p. 21.

- Australian Government: Department of Health. (n.d.). Medicare Benefits Schedule, Provision of Focussed Psychological Strategies Services by Allied Health Provider, M7 Associated Notes. Retrieved from http://www9.health.gov.au/mbs/fullDisplay.cfm?type=item&q=80120&qt=ItemID (Accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Australian Government: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2019). Mental health workforce. Retrieved from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/6975aa54-246d-426e-9e33-fec8ec7ce105/Mental-health-workforce-2019.pdf.aspx (Accessed May 2022).

- Australian Counselling Association. Care Workforce Labour Market Study Submission. (June 2021). Retrieved from: https://www.theaca.net.au/documents/ACA%20Care%20Workforce%20Labour%20Market%20Study%20Submission.pdf (Accessed 6 April 2022).

- Psychotherapy and Counselling Federation of Australia. Federal Election Statement 2022. Retrieved from https://pacfa.org.au/common/Uploaded%20files/PCFA/Documents/Submissions/PACFA_FederalElection_04_2022_Statement_final.pdf (Accessed 6 April 2022).

- Duke, Jennifer. (2020, April 29). Tax multinationals and fix mental health before union laws: Lambie. Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/tax-multinationals-and-fix-mental-health-before-union-laws-lambie-20200429-p54o5q.html (Accessed March 2022).

- Australian Government: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Medicare-subsidised mental health-specific services. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mental-health-services/mental-health-services-in-australia/report-contents/medicare-subsidised-mental-health-specific-services (Accessed 27 May 2022).

- Australian Psychological Society. (2022, February 24). 1 in 3 psychologists are unable to see new clients, but Australians need help more than ever. Retrieved from https://psychology.org.au/for-members/publications/news/2022/australians-need-psychological-help-more-than-ever (Accessed 20 May 2022).

- Hewson, Georgie. (2022, February 1). Counsellors pleased for Medicare cover to ease regional mental health crisis. ABC News. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-02-01/covid-mental-health-counsellors-call-for-medicare-cover/100794582 (Accessed 31 March 2022).

- Page, Cate. (2020). Counselling Efficacy between Professions: A Comparison between Counsellors, Psychologists and Social Workers in Employment Assistance Programs. Retrieved from https://www.pacfa.org.au/common/Uploaded%20files/PCFA/Research%20studies/Counselling%20Efficacy%20between%20Professions%20(1).pdf. (Accessed 27 May 2022). pp. 10-12

- Bloch-Atefi, Alexandra, Day, Elizabeth, Snell, Trian, & O’Neill, Gina. (2021). A snapshot of the counselling and psychotherapy workforce in Australia in 2020: Underutilised and poorly remunerated, yet highly qualified and desperately needed. Retrieved from: https://pacja.org.au/2021/10/a-snapshot-of-the-counselling-and-psychotherapy-workforce-in-australia-in-2020-underutilised-and-poorly-remunerated-yet-highly-qualified-and-desperately-needed-2/ (Accessed 3 June 2022).

- Cumming, Sarah. (2021, October 13). Mental health nurses seek urgent access to Medicare subsidies amid growing crisis. ABC News Online. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-10-13/access-to-medicare-subsidies-amid-growing-crisis/100428270#:~:text=The%20Better%20Access%20Initiative%20provides,patients%20for%20mental%20health%20services (Accessed 26 May 2022).

- Davey, Amanda. (2017). GP consultation times: Where we sit on a world scale. Retrieved from: https://www.ausdoc.com.au/news/gp-consultation-times-where-we-sit-world-scale-0 (Accessed 8 June 2022).

- Cassidy, Jude., Jones, Jason, D., & Shaver, Phillip, R. (2013). Contributions of Attachment Theory and Research: A Framework for Future Research, Translation, and Policy. Development and Psychopathology, V24(4). Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4085672/ (Accessed 24 May 2022).

- Shaver, Phillip., R., & Mikulincer, M. (2021). Enhancing the “broaden-and-build” cycle of attachment security as a means of overcoming prejudice, discrimination, and racism. Attachment and Human Development, 24(3), pp.260-273. Retrieved from: https://www-tandfonline-com.torrens.idm.oclc.org/doi/full/10.1080/14616734.2021.1976921 (Accessed 8 June 2022).

- Harvard University: Center on the Developing Child. An Action Guide for Policymakers – Three Key Points from Working Paper 15: ‘Connecting the Brain to the Rest of the Body’ Health and Learning Are Deeply Interconnected in the Body. Retrieved from https://46y5eh11fhgw3ve3ytpwxt9r-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/2020_WP15_actionguide_FINAL.pdf (Accessed 24 May 2022).

- Green, Janet., Staff, Lynette., Bromley, Patricia., Jones, Linda., & Petty, Julia. (2020). The implications of face masks for babies and families during the COVID_19 pandemic: A discussion paper. Journal of Neonatal Nursing. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7598570/ (Accessed May 2022).

- United Nations. (2020, 13 May). Policy Brief: COVID-19 and the Need for Action on Mental Health. Retrieved from https://unsdg.un.org/resources/policy-brief-covid-19-and-need-action-mental-health (Accessed March 2022). p. 7.

- Australian Government: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Births, Australia. Retrieved from https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/births-australia/latest-release (Accessed 24 May 2022).