A. Introduction: If crime is the question, is prison the answer?

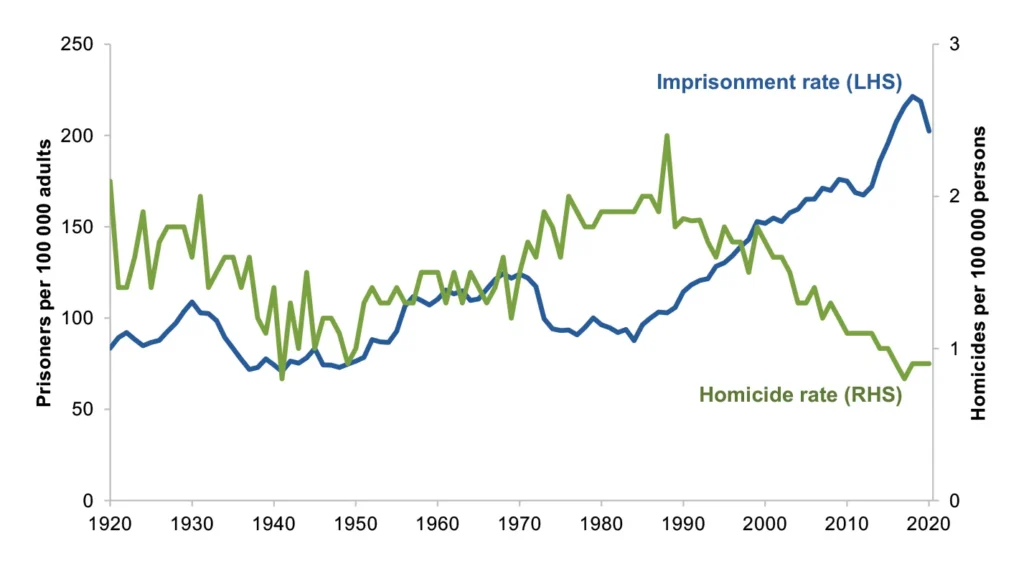

The crime rate for homicide in Australia has been declining since the 1990s, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Criminologists consider homicide rates a useful indicator of trends in the incidence of violent crime because almost all cases are reported to police which means data are available over a longer period. In 1990, the crime rate for homicide stood at 2.19 per 100,000 population and had fallen to 0.74 per 100,000 population by 2021, the lowest point in over three decades. Chart 1 shows the trend line of the homicide crime rate not only since 1990 but over the last 100 years, since 1920.[1] It is likely that the long-term decline in rates of homicide in Australia will continue.

Chart 1: Australia’s murder/homicide rate, 1990-2023

Source: Productivity Commission/Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS)

Meanwhile, as Chart 1 also indicates, over the past 100 years and, specifically, since 1990, Australian rates of incarceration have, on the whole, continued to rise. According to the ABS, over the decade to 2022, Australia’s prison population increased both in number and as a proportion of the population. Between 1994 and 2022, the number of prisoners increased by 26,024 from 16,946 to 40,600.[2] When population growth is taken into account,[3] the rate of imprisonment increased from 128 to 214 per 100,000 adult population.[4]

Those currently in Australian prisons are there for one of two reasons: they have either been remanded in custody pending trial or are serving a custodial sentence after having been convicted by a court. Recent research indicates Australia continues to send more people to prison even though crime rates are falling. Rising rates of incarceration have prompted criticism from scholars, such as economist and politician Andrew Leigh, who decries what he has described as “Australia’s second convict age”.[5]

Punishment, or the threat of punishment, alone will not prevent crime. As this report will argue, policing strategies together with changes in economic and social factors are likely to have played a significant part in the decline of crime rates. Even so, the absolute effect of prison entails that when willingness to use prison as punishment weakens, crime rates can be expected to rise. A question therefore arises as to whether there is a close correlation between rates of imprisonment and rates of crime. One factor to consider is the marginal effect of prison — that is, whether for each additional person sent to prison, there is a corresponding reduction in the rate of crime.

This report will investigate the place and purpose of prison in contemporary Australian society and assess the part it plays in our criminal justice systems. It will also argue, in line with recent research, that the marginal effect of prison in Australia appears to be declining. But does this account for rising rates of incarceration? First, however, it is important to consider the principal purposes of prison. The report will then proceed to evaluate the merits and problems of prison within the context of the broader criminal justice systems.

B. The purposes of prison

Prison can be understood as serving four principal purposes:

- Retribution: prison punishes by depriving an individual of their liberty and holding them to account for their misdeeds. The grounds for prison’s retributive purpose is justice: a convicted felon gets a deserved penalty.

- Incapacitation: prison protects society by removing from circulation individuals who are deemed to pose a threat to public safety. If dangerous offenders are put in prison, the opportunities for them to commit crimes are reduced.

- Deterrence: prison aims to deter crime by discouraging individuals from committing offences because the consequences of getting caught and convicted could well lead to incarceration and loss of liberty, possibly for an extended period.

- Rehabilitation: prison aims to rehabilitate offenders and prepare them for release in the hope of reducing the risk of reoffending.

The four purposes of prison need to align as much as possible, but sometimes they can conflict. For example, while community desire for justice may be satisfied by a severely punitive prison sentence for a particular crime, such a sentence might cause excessive harm to the offender and their family and actually increase the risk of reoffending. “If this is the case, there can be conflict between justice for victims and offenders, between justice and community safety, and between community safety in the short term and in the long term.”[6]

C. The purpose of a criminal justice system

A criminal justice system comprises: law enforcement, which is responsible for preventing and detecting crime; courts, which determine the guilt or innocence of offenders and the sentence awarded to those found guilty; and corrective services, which run prisons, monitor offenders and provide rehabilitation services. In Australia, the states and territories have primary responsibility for administering systems of criminal justice. In general, the broad objectives of a criminal justice system are:

- Ensuring the safety of the community by deterring offenders, incapacitating those convicted by the courts, and rehabilitating offenders in preparation for their release;

- Securing justice for victims by imposing appropriate punishment, and justice for offenders by ensuring punishment is proportional to the crime;

- Establishing community confidence in the criminal justice system by efficient detection and punishment of offenders.

Some critics of Australia’s criminal justice systems argue that appropriate reform must begin by making a distinction between those convicted of violent and non-violent offences. They make this distinction on the assumption that violent offenders pose a greater risk to community safety than non-violent offenders.[7]

However, this argument assumes that ‘risk’ and threats of ‘harm’ tend to be posed only by acts of physical violence. Fraud is one example of a crime that poses no threat of physical harm; but it would be wholly mistaken to argue, on this basis, that fraudsters pose no ‘risk’ to the community or that their actions cause no ‘harm’. Indeed, in terms of white-collar crime, the issue is not so much one of risk as it is of recognising the serious harm — both financial and psychological — they cause to victims. Drug offences, such as possession, are also examples of offences that, while non-violent, do pose both a risk to the community and the threat of harm.

Against this wider understanding of ‘risk’ and ‘harm’, defenders of prison argue that the distinction between violent and non-violent offences is blunt and simplistic — and that without prison, society would simply be much more dangerous for everyone. Prison, therefore, is held to be an indispensable component of the criminal justice system.

D. On keeping crime rates low

Nearly 43,000 Australians were behind bars as of June 2021 and this coincided with the lowest crime rate in nearly three decades (0.74 per 100,000 population at June 2021). However, in a report published in 2021, the Australian Productivity Commission found the rise in imprisonment could not, alone, account for changes in the amount (or type) of crime. Rather, the Commission found that the rate of imprisonment was to be understood in terms of two broad changes.

First, changes to both the nature and the reporting of crime were affecting levels of imprisonment. Rates of some crimes — such as homicide — have declined whereas rates for others, such as sexual assaults and drug-related offences, have increased. This has been accompanied by an increased willingness to report some kinds of crime, such as domestic violence, as the social stigma around victims of such offences has lifted.

The second broad change has occurred in criminal justice policy, a development made more complex by Australia’s nine different jurisdictions (one for each state and territory, and the federal system). For example, bail has been made more difficult to access in some jurisdictions, remand has become a default position in others, and a number of jurisdictions have introduced prison-based mandatory sentencing.[8]

The commission noted three possible explanations for the coincidence of rising imprisonment and falling crime rates:

- Falling crime rates are a direct result of sending more people to prison;

- Australian systems of justice have become more punitive over time;

- Changes to the nature of crime and the characteristics of offenders mean that a smaller pool of offenders face a higher chance of imprisonment.

Whereas each of these factors is likely to have contributed to declining rates of crime, the Commission found “the evidence suggests that changes to the risk of imprisonment and sentence length may have played a smaller role than other criminal justice policies (particularly policing policies that affect the risk of arrest or conviction).”[9]

This finding is substantiated by an exhaustive study conducted by Australian criminologists, Professor Don Weatherburn and Sara Rahman, in which they tested 16 theories that purported to explain falling crime rates, including imprisonment. They argued that falling crime rates cannot be attributed to any one factor. In particular, they emphasised their finding that the relationship between crime and imprisonment rates is weak:

At any given time, there are multiple factors pushing different types of crime up (e.g. poverty, drug and alcohol use, new criminal opportunities) and multiple factors pushing those same types of crime down (weak informal social controls, new forms of surveillance, improvements in policing. The observed trend in crime at any given time hinges on the balance between these two sets of factors.[10]

When a series of identifiable factors pushing down rates for certain kinds of offences (such as theft and robbery) exceeds those pushing them up, crime rates will fall. “Since 2001, [Australia] has been profiting from a combination of forces that have pushed most crime rates down.” They concluded that, in the short term, the most effective tools in preventing and controlling crime “are those that block the opportunities for crime, increase the risks of apprehension and/or remove the rewards.”[11] In terms of crime control, increasing the number of police is therefore more likely to be effective in reducing crime than increasing the severity of the sanctions imposed on offenders.

Prison may work as an indispensable part of the solution to crime, but not in isolation; to hold otherwise has, in the view of critics such as Vivien Stern, “a superficial simplicity that makes it difficult to resist.” But this superficial simplicity, and gains in the short-term, mask the financial and social cost of using incarceration to solve society’s problem of crime.[12]

E. Going to prison in Australia

Accordingly, any considered examination of Australia’s incarceration rates must go beyond an overly simple categorisation of offenders into those who are violent or non-violent, or who are deemed to be ‘safe’ or who present a ‘risk’ to wider society. An evaluation of risk, safety and harm caused may well conclude that imposition of a custodial sentence is warranted for many non-violent offenders.

However, writing in 2020, Leigh argued that despite what he refers to as “Australia’s Second Convict Age”, increases in imprisonment bring diminishing marginal returns both in terms of incapacitation and deterrence. In the case of incapacitation:

This is because criminal careers are relatively short, with the age-crime curve peaking in the late-teens and early-twenties. As a result, sentences that go beyond the age range when individuals are most likely to commit crimes are likely to have a smaller impact on public safety.[13]

And in the case of deterrence, Leigh notes that “decreasing returns arise because the benefits of crime are immediate, while the costs are delayed. Higher discount rates in the target population will dampen the effect of incarceration on crime.”[14]

At the same time, Leigh notes that Australia’s propensity to send people to prison has significant implications: employment prospects for released prisoners are poor; health is impacted adversely; the risk of homelessness is high; children of those imprisoned suffer; and many released prisoners reoffend.

Leigh joins other scholars in cautioning against a simplistic assumption that crime rates fall when incarceration rates rise. Prison is more likely to have an impact on rates of crime when those incarcerated are in their peak offending years; but as the prison population ages, the impact of incarceration on rates of crime will diminish.

Leigh argues that there are other more likely explanations than incarceration for Australia’s falling crime rate; such as better community policy, immigration, rising incomes, the legalisation of abortion and the removal of lead from petrol.[15] While prison has an important role to play in combatting crime and ensuring serious offenders receive a just punishment, Leigh is one among a number of scholars who argue that current rates of incarceration are higher than necessary to achieve this key objective of the criminal justice system.

Indeed, the results of Leigh’s study of Australian rates of imprisonment are consistent with findings from other recent investigations of the social and economic impact of incarceration, such as a report from the Queensland Productivity Commission (QPC) published in 2019. Although charged with addressing prison policy in Queensland rather than the Commonwealth, the QPC found that rising imprisonment rates were driven not by crime rates but by adoption of certain policies within the Queensland criminal justice system. These policy changes include increasing the efforts and efficacy of the police; increased numbers of prisoners held on remand; and an increase in the use of prison sentences over other options, such as community service orders.[16]

Criminal justice policies have a very significant impact on rates of imprisonment. However, as this report will argue, any serious attempt to review and reform Australia’s prison systems entails recognising that while fewer crimes are being committed, more people are likely to end up in prison due to the operation of this country’s various criminal justice systems.

TEXT BOX 1. Why punish?

Any modern democracy should be able to account for the ways in which it organises its system of criminal justice — in particular, the system of punishing those convicted of criminal offences — and for the objectives such a system is designed to pursue. A broad and necessarily simplified account of theories of punishment divides them into two broad theories.

First, utilitarian theories of punishment justify the penalties imposed upon convicted criminals in terms of the good consequences such punishment is designed to bring about. For the utilitarian, punishment imposes suffering which, while not good in itself, can be only justified if the good consequences, such as prevention or deterrence of criminal behaviour, outweigh the harm doing to the offender (deprivation of liberty). Presumably, if the consequences of punishment led to an increase in crime, utilitarians would be obliged to abandon punishment and seek a more effective and consequentially desirable way of dealing with offenders.

Punishment which causes consequences that are worse than not punishing cannot be justified by a utilitarian approach. Strictly, a utilitarian approach to punishment might hold that the good consequences of eradicating crime from society (through deterrence and prevention) could outweigh the bad consequences of punishing the innocent and thereby justify imprisoning the innocent. However, the innocent are not punished for crimes committed by others because it is considered unjust to use the innocent as a means for procuring a wider social benefit.

Second, retributive theories of punishment justify punishment because the offender has voluntarily committed an offence. Retributive theories hold that suffering is not bad in itself and that those who do wrong deserve to suffer for what they have done regardless of the consequences, (whether personal or social) of the punishment.

Clearly, retributive theories of punishment do not aim to reduce crime; they simply hold that it is just to punish the guilty because their punishment is deserved. This would be the case even if punishment were to lead to an increase in crime since the retributivist pays no heed to the consequences of punishment. However, one objection to retributive theories of punishment is that they do not justify why, exactly, it is that wrongdoers deserve to suffer for past acts; nor do they justify the assertion that it is the function of the state to ensure wrongdoers get their deserts.[17]

In response to the weaknesses of both utilitarian and retributive theories of punishment, some ‘mixed’ theories of punishment have developed. Broadly, these accept the place of retribution as a secondary element but assert the primary goal of a theory of punishment must be to deter criminal behaviour and thereby protect innocent victims of crime from having their rights violated.

One such theory is the moral education theory of punishment, the object of which is the moral instruction and improvement of the wrongdoer. According to the moral education theory, “the state is not concerned to use pain coercively so as to progressively eliminate certain types of behaviour; rather, it is concerned to educate its citizens morally so that they choose not to engage in this behaviour.”[18]

Punishment is not justified primarily as a means to achieve the social goal of reducing crime rates. Rather, justification lies in the hope that the person who experiences it will thereby benefit and, should the offender choose to listen, gain moral knowledge. This, in turn, can lead to the wider social benefit of educating the community at large about the wrongfulness of the offence. Unlike utilitarian or retributive theories of punishment, an educative theory regards “the moral good which punishment attempts to accomplish within the wrongdoer [as] something which is done for him, not to him.” [Italics in original][19]

However, critics of this theory of punishment question whether or not it is the role of the state to punish by means of moral education. By presupposing ethical objectivism where there is deemed to be general agreement about what counts as good and what is bad, critics argue that the theory threatens to override the moral autonomy of the individual. But where an individual exercises moral autonomy by making decisions that result in harm to others in the community, surely the state is entitled to intervene and decide and enforce certain moral positions.

F. Four criminal justice policy challenges

A number of factors determine policy concerning prisons, including who is sent to prison, and why. The term “penal climate” has been used by some criminologists to describe this matrix of factors and has been invoked favourably by Australian criminologist, Arie Freiberg, who has adopted the definition offered by UK criminologist, David Green: “[Penal climate is] the degree of public, media and political pressure exerted upon politicians and sentencers to act toughly or punitively on penal policy issues.”[20] There are four key factors in Australia’s penal climate that have a particular bearing on the high rates of incarceration in Australia.

- Sentencing and mandatory sentencing

Although he recognises that many of the wider factors identified by Green also have a part to play, Freiberg narrows his own evaluation of the Australian penal climate specifically to an examination of sentencing policies. All states and territories have enacted sentencing statutes that provide a framework for the courts. These frameworks now determine the basic structure of Australian sentencing policy, although the fundamental principle that guides sentencing in Australia remains that of ‘proportionality’ — that is, the severity of the punishment should reflect the seriousness and gravity of the offence, and should be no greater than the offender’s moral culpability.

However, courts may find themselves constrained by the sanctions set in sentencing legislation. In Freiberg’s view, the impact of this legislation has been to shift the balance of powers between the legislature, the courts and the executive: “the enlarged role of victims and the public in the development of sentencing policy has added to the complexity of the legislative process.”[21] Rising rates of incarceration are part of the cumulative effect of this increased complexity which has led to what Freiberg describes as “the increasingly punitive penal climate”.

One significant factor that has contributed to this climate is so-called ‘penal populism’ whereby politicians and the media appeal to public anxiety about crime rates and what are considered to be ‘light’ sentences handed down by the courts. Public expression of this anxiety often leads to development of excessively harsh sentencing policies. Penal populism has been an especially influential factor in shaping sentencing policies concerning sex offenders and youth crime.

New Zealand criminologist John Pratt argues that the changing nature of media and public decline of deference to the judiciary and the courts are among the factors that have contributed to the rise of penal populism. While not an inevitable phenomenon, this rise has been at the expense of prisoners’ rights as well as on the quality of criminal justice systems.[22]

While exercise of judicial discretion is an essential component of the sentencing process, it is undermined by legislative prescriptions for sentences; which can thereby reduce the determination of a sentence to a mechanical calculation. The High Court has sought in a number of cases, notably Markarian v The Queen, to defend the exercise of judicial discretion in sentencing.

In Markarian, the High Court ruled that judges should weigh all the factors of the case by a process of “instinctive synthesis” and so arrive at one final sentence. They should not determine a sentence simply by quantifying all the individual factors and adding them up to arrive at a sentence. The maximum penalty set out in legislation provides only a basis for comparing the case before the court and the worst possible case. Maximum penalties reflect only the legislature’s assessment of the seriousness of the offence, providing guidance for the court in determining an appropriate sentence.[23]

Australian courts tend to view sentencing as an art that defies mathematical precision, rather than as a science. The desired outcome sought by the court is “consistency in the application of sentencing principles, not consistency of outcome as expressed in terms of numerical equivalence.”[24]

Even so, and notwithstanding firm resistance at times from the High Court, mandatory sentences imposed by the legislature can be hard to avoid; and this form of imposition has a directly identifiable impact on rates of imprisonment.

The fact is that some people are in prison because, having been convicted of certain offences, that is exactly where legislators want them. However, once in prison, there are other factors whereby legislators may determine when a prisoner may be released and which overrule any exercise of discretion by parole boards and others involved in the evaluation of a prisoner’s rehabilitative progress.

One such factor, which applies in NSW, is legislators setting standard non-parole periods (SNPP).[25] Introduced by NSW in 2003, the SNPP is a legislative reference point the court must consider when sentencing: the period that must be served before eligibility for parole.

According to the Judicial Commission of NSW, both the severity of penalties and the length of sentences have increased since the introduction of SNPPs for certain offences, and there has been greater consistency and uniformity in sentencing:

The largest sentence increase was for the offence of sexual intercourse with a child under the age of 10 years, with the median full term of sentence increasing by 60% from 5 years to 8 years, and the median non-parole period increasing by 42% from 3 years to 4 years 3 months for offenders who pleaded guilty.[26]

With the passage of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Amendment Act (NSW) 2007, SNPPs now apply to around 35 serious criminal offences. When the court decides to depart from the standard period, it must make a record of its reasons for doing so.

The Judicial Commission of NSW found that the introduction of SNPPs had an overall effect on rates of incarceration and that the number of people in prison serving these periods had increased. The system of SNPPs sets NSW’s criminal justice system apart from the systems in other Australian jurisdictions.

- Remand

According to the latest data from the ABS (June 2022), there are currently around 15,200 prisoners being held on remand — that is, awaiting trial or sentencing. This amounts to approximately 37% of the total prison population. This, in turn, equates to 59 prisoners on remand per 100,000 of population; which is slightly lower than the current OECD average of 75 prisoners on remand per 100,000 of populations.

The number of those held on remand in Australia represents an increase of 16% from two years before (June 2020). Between June 2021 and June 2022, the number of prisoners on remand decreased by 2% to 14,864 prisoners. Furthermore, the average time spent on remand has also increased from 4.5 months in 2001 to 5.8 months in 2020.[27] However, due to a decrease in the number of sentenced prisoners, the proportion of unsentenced to sentenced prisoners increased by 2% from 35% to 37%.[28]

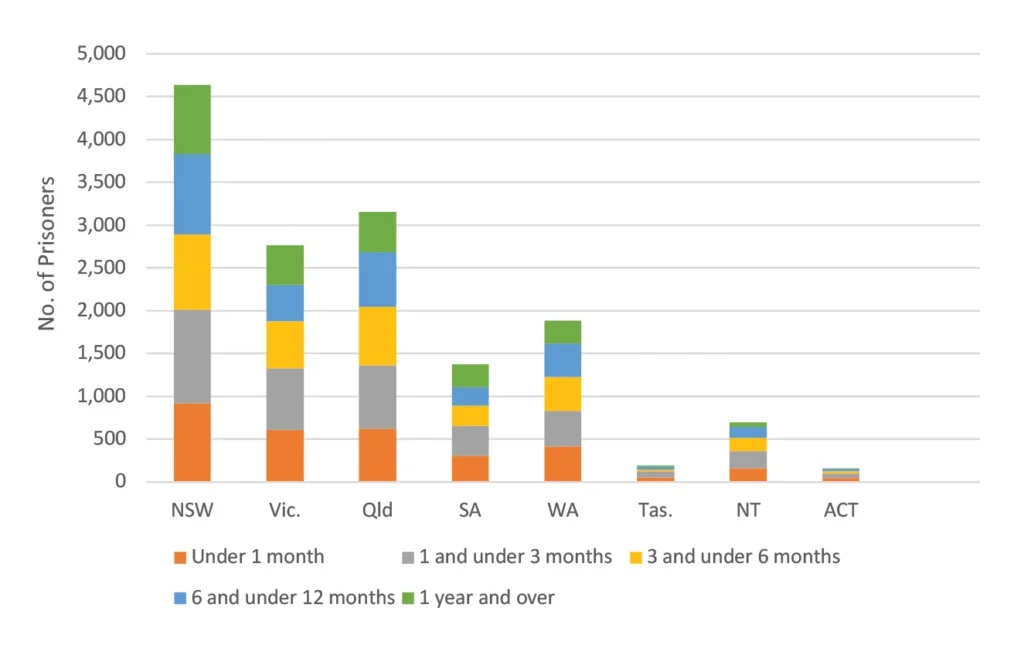

Chart 2: Time spent on remand by State and Territory in 2022

Source: Prisoners in Australia, 2022, States and Territories, Table 32

As is clear from Chart 2, NSW has the largest number of prisoners held on remand. The chart also shows that the length of time spent on remand is reasonably well distributed across each of the states and territories.

Prisoners on remand face a great deal of uncertainty as they wait for trial and the possibility of a custodial sentence. The Productivity Commission noted in its report that remand imposes a particular strain on the mental health of those held on remand leading to higher rates of suicide in that portion of the prison population. It went on to observe that:

The uncertainty associated with this for prisoners, victims and corrective services limits access to available services such as education and training and rehabilitation programs. Remanding people in custody means that governments face the fiscal costs of imprisonment itself.[29]

In general, a prisoner is likely to be held on remand for one or more of a number of reasons:

- Seriousness of the offence: if the offence committed is more serious, such as homicide and other acts intended to injure others;[30]

- Risk of re-offending: if it is judged that the accused is at high risk of re-offending while on bail;

- Risk of self-harm: if the accused is considered to be at risk of self-harm;

- Protecting others: if the victim or other individuals involved in the case are considered to be at risk;

- Cannot meet bail conditions: if the accused is unable to meet bail conditions set down by the court;

- Breach of bail conditions: if the accused was previously released on bail but breached bail conditions.

A number of factors explain the increase in prisoners currently held on remand. One is the delay in bringing matters to trial, especially in higher courts (that is, the Supreme Court and above).[31] Other factors included an increase in the number of bail breaches and the use of remand as an increasingly common judicial response.

In its analysis of this problem, the Productivity Commission reported that the over-reliance on remand has arisen “both from systemic issues, such as under-resourced prosecution services, inadequate legal aid funding and a lack of alternatives, as well as from judicial culture and practice.”[32]

Clearly, any reduction in the numbers of prisoners held on remand would ease the overall size of the prison population. A number of policy options for achieving this are open to governments; including reform of bail laws. Reform would entail re-evaluating each of the six reasons for detaining a prisoner on remand and considering the option of alternative forms of bail, such as electronic monitoring (by means of GPS tracking devices attached as ankle bracelets) for offenders deemed to be of lower risk to the community.

Unlike prison, electronic monitoring does not actually prevent offenders from committing new crimes; “nothing incapacitates repeat offenders as effectively as confinement in a secure facility.”[33] Nonetheless, reducing incarceration for low-risk offenders can have both social benefits for offenders and their families, and financial benefits for the state.

Increased funding for legal aid services could also allow alleged offenders to be properly represented during the bail application process; thereby helping avoid periods of remand.

Affording courts greater discretion in the imposition of community-based sentencing options — such as fines and community service — could also provide an alternative to prison for offenders posing a lower risk to public safety.

- Bail policy

Access to bail has become harder due to changes made to bail policy. Recent research has found that a former emphasis on using bail to ensure court attendance has given way, since 2010, to an emphasis on mitigating the risks of offending while on bail.[34] This has meant that harm mitigation has increasingly taken priority over the fundamental rights of the accused.

For example, in August 2023, the Victorian government proposed reform to the state’s bail laws that would allow people charged with minor, non-violent offences to be spared remand and granted bail more easily. In particular, those unlikely to receive a custodial sentence in the event of conviction would not be remanded; those who have never been convicted of a crime would be granted bail more easily; and reforms would help children to be kept out of the criminal justice system thereby leading to decline in the incarceration of young and the concomitant risk of youth recidivism. The Bail Amendment Bill 2023 (Vic) passed both houses of the Victorian parliament in early October 2023 and, having received Royal Assent, will come into effect in early 2024.

On the other hand, changes to the Bail Act 2013 (NSW) enacted in June 2022 mean that bail will not be granted to a prisoner after conviction but before sentencing (when the sentence will be served by full-time detention) unless special or exceptional circumstances can be established.[35] This, in turn, affects the capacity of the court to direct offenders who have not committed serious offences into early rehabilitation programs. Amendments to bail policy, such as those implemented in NSW, reflect a broader trend towards tightening access to bail in all Australian jurisdictions. Furthermore, they reflect a reluctance to embrace:

The principle that the presumption of innocence and the other fundamental rights of the accused should be a significant consideration in the shaping of bail laws. The trajectory of adjustments to the rules on bail remains punitive – a trend that can be traced back for more than three decades.[36]

Bail policy needs to strike a balance between upholding the rights of the accused (who may be found innocent) and safeguarding the community where an individual may pose an unacceptable risk to the public. Situations will arise when there is a failure to strike such a balance: a person may be denied bail but subsequently be acquitted; a person granted bail may commit further offences while on bail.

However, many scholars believe situations such as these (sometimes described as “trigger cases”) do not warrant an entire rewriting of bail policy.[37] Rather, specific decisions about the granting or denial of bail warrant review rather than legislative reform. Review can “reveal much about whether the bail decision was appropriate and whether there are issues in the decision-making process that require redress.”[38]

Even so, the impact of tougher bail policy (and, indeed, tougher sentencing policy) on imprisonment rates needs to be assessed with care. In a case study examining imprisonment rates in NSW, Weatherburn found little evidence that either had the impact often assumed on either the length or the likelihood of a prison sentence. The reason for the assumption is that since the prison population comprises both remand and sentenced prisoners, an increase in the number of inmates is attributed to changes to policy. But as Weatherburn argues:

Bail and sentencing policy, however, are not the only factors that determine the size of a State or Territory’s prison population. Crime and policing policy also have a powerful influence on the prison population via their effect on number of people arrested and the offences for which they are arrested.[39]

Weatherburn argues the influence of policing policy is significant because if the probability of arrest remains constant (along with the probability of conviction given arrest, and the probability of imprisonment given conviction), “a rise in crime will automatically generate an increase in prison receptions.” [40]

It is beyond the scope of this report to investigate the impact of policing policy either on rates of arrest or rates of imprisonment. However, it is important to note that policing policy does have a significant impact on both and that, in Weatherburn’s view, one important explanatory factor accounting for changes in policy may be the growth of managerialism (using the example of the NSW public sector). For the purposes of the present report, it is sufficient to note that, in terms of rates of incarceration, changes in policing policy do influence the rate of prison arrivals because, like crime, they can influence rates of arrest.

- Recidivism

The re-entry of previously incarcerated individuals into the criminal justice system poses a persistent challenge to the justice system. Re-offending rates show “the extent to which people who have had contact with the criminal justice system are re-arrested or return to corrective services.”[41] For the reporting period 2021-2022, the Productivity Commission found that 43% of prisoners released in the period 2019-20 after serving a sentence had returned to prison within two years. When those served with community corrections orders are included, the total number of offenders who had returned to corrective services with a new correctional sanction, within two years was 52%.[42]

Australia’s national rate of recidivism is high. The most reliable recent data available is nearly ten years old; however, as of the period 2014-15, the reconviction rate in Australia after two years was 53% as compared with other OECD countries, such as Austria (26%), France (40%), Norway (20%) and Denmark (29%).[43] It should be noted, however, that international comparison of recidivism rates is inexact because of differences both in reporting and the operational definition of ‘recidivism’.

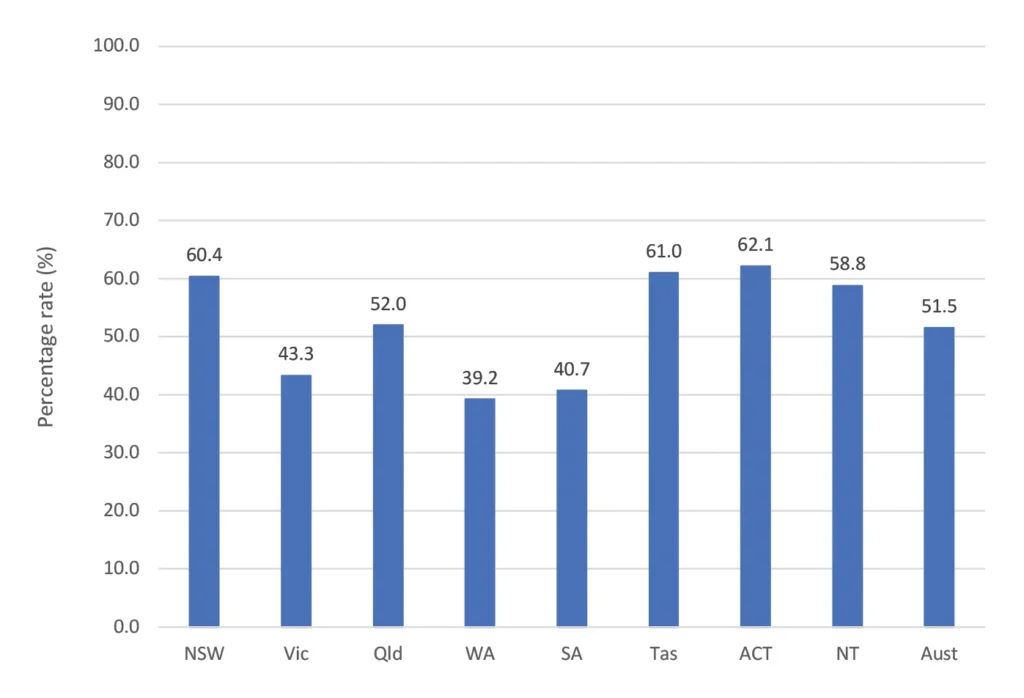

Recidivism rates in Australia exhibit considerable disparities across states and territories (see chart 3). Western Australia stands out with a relatively lower recidivism rate of 39% two years after release. This contrasts sharply with New South Wales, where the recidivism rate soars to 60%, nearly two-thirds higher. These regional disparities raise questions about the influence of local policies, rehabilitation programs, and socioeconomic factors on recidivism outcomes.

One significant factor contributing to high rates of recidivism in Australia is the prevalence of short-term sentences. For the reporting period 2021-2022, more than 33 per cent of prisoners received sentences of less than six months, with 66 per cent of these short-term sentences being served for non-violent offences.[44]

The reason for this impact of short sentences is that in addition to being very disruptive to a prisoner’s life, such sentences are commonly imposed for less severe offences or as a response to lower-risk offenders. Yet they afford few — if any — opportunities for participation in rehabilitation and reintegration programs, which heightens the risk of re-offending upon release.

Consequently, individuals serving short sentences are more likely to re-offend and re-enter the criminal justice system.[45] The paradoxical situation is that by not spending enough time in prison serving an initial sentence and participating in rehabilitation programs, an individual is more likely to re-offend after release, thereby perpetuating a cycle of interaction with the criminal justice system.

However, it is not only those receiving short sentences who are likely to return to prison. Health and social factors, such as mental illness, substance abuse, trauma and inability to gain employment, as well as lack of rehabilitation programs, are also likely to play a significant part in frustrating efforts of released prisoners to adjust to wider society.[46] The preponderance of chronic offenders exerts significant pressure on correctional institutions and accentuates the pressing need for interventions that delve deeper into the underlying causes of persistent criminal behaviour.

Chart 3: Adults released from prison who returned to prison or to corrective services with a new correctional sanction within two years

Source: Report on Government Services, 2023, Justice data table

Disparities between rates of recidivism for Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians are a stark and distressing reality. Nearly two-thirds (64%) of released Indigenous individuals re-enter the correctional system within two years. This disparity is underpinned by an interplay of factors, including early entry into the criminal justice system, heightened exposure to risk factors before, during and after imprisonment, and shorter, yet more frequently recurring, periods of time spent in prison.

Rates are further exacerbated by major backlogs in the court system. This was highlighted, for example, by the NSW Auditor General’s Report for 2015 which found that the backlog of cases in the NSW District Court had continued to grow since 2011. In 2015, the backlog of cases stood at 1,976. The NSW District Court estimated that in 2015, 850 people were on remand contributing to prison overcrowding and costing the state $60 million per year.[47]

Similar backlogs afflict magistrate-level courts, with New South Wales performing relatively better and Victoria experiencing the worst delays. In the period of the financial year 2021-22 (the 12 month period to 30 June 2022), the backlog of criminal cases in the NSW District Court stood at 20% whereas the comparable rate for the NSW Supreme Court for the same period was 23%. These rates are more favourable than those for Victoria, for example, which stood at 33% (District Court) and 31% (Supreme Court).[48]

In general, backlogs in the court system contribute to increasing recidivism rates; as inmates facing remand experience adverse effects which “negatively impact all aspects of custodial life and could ultimately result in higher re-offending rates”.[49]

In addition to the factors contributing to recidivism rates, the criminogenic nature of prisons further exacerbates the problem because, as noted above, the experience of imprisonment can make individuals more likely to engage in criminal activities upon release. [50] Several interrelated factors contribute to the criminogenic effects of incarceration. These include the association with criminal networks within prisons, the normalisation of criminal behaviour, learned criminal behaviour, and stigmatisation and limited opportunities post-release.

Effective programs for rehabilitation have an important part to play in reducing the criminogenic impact of prison. However, the efficacy of such programs is contingent upon two key factors: first, the availability of programs; and, second, the rate of uptake. According to Leigh, in terms of rehabilitative effect, “prison sentences are no more effective than non-custodial approaches, such as community work, electronic monitoring and fines.”[51] Weatherburn reached a similar conclusion and has remarked that, “in the case of electronic monitoring, the risk of re-offending is lower.”[52]

The period of transition to life outside prison is a pivotal juncture in an individual’s journey through the criminal justice system. It is a critical phase which presents additional opportunities to reduce re-offending than within the structural prison system.

Homelessness is a significant concern for individuals leaving prison, with more than 50% finding themselves without stable housing and around 44% expected to stay in short-term or emergency accommodation.[53] Homelessness is thereby a critical risk factor that increases the likelihood of returning to prison. Without a stable place to live, individuals face immense challenges in finding stable employment, accessing support services, and maintaining a legal lifestyle. The absence of a stable home can lead to feelings of hopelessness and despair, pushing some individuals back into criminal activities as a means of survival.

In addition to the problem of finding somewhere to live, lack of access to essential services presents another formidable barrier to successful reintegration. The absence of health coverage, such as possessing a valid Medicare card, adds to the challenges faced by those leaving prison. A substantial 36% of individuals either do not possess a valid Medicare card or are uncertain about their health coverage upon release.[54] Employment is another challenge; 62% of those leaving prison have no paid work within two weeks of release.[55]

Similarly, the absence of access to disability services can impede the reintegration process for those with disabilities. Upon release, people may require support for a range of issues, including substance abuse, mental health, and disability-related needs. The absence of access to drug and alcohol services can hinder the ability to overcome addiction, while the lack of mental health services may prevent them from addressing the underlying psychological issues that contribute to criminal behaviour.

The Justice Reform Initiative (JRI), an advocacy group committed to reducing reliance on incarceration as a form of punishment, has argued these challenges represent critical structural issues that demand immediate attention. [56]

Many of those currently serving a prison sentence have been in prison before, suggesting that reintegration programs available to prisoners completing their sentence are likely to be too few, too ineffective, or both. In order effectively to address recidivism and promote successful reintegration, it is imperative to recognize that an individual leaving prison needs comprehensive support, services and employment opportunities.

G. Policy challenges for government

“Prison walls serve a dual purpose,” notes Australian criminologist, Peter Norden. “They keep prisoners from escaping and they keep the community outside, and ignorant of what goes on behind those prison walls.”[57] However, as this report has argued, there is no simple correlation between rates of incarceration and rates of crime. Indeed, British criminologist Jock Young has warned against oversimplifying the complex, interactive nature of the social world where one event can influence another in ways that are not easy to calculate:

The crime rate is affected by a large number of things: by the level of deterrence exerted by the criminal justice system, to be sure, but also by the levels of informal control in the community, by patterns of employment, by types of child-rearing, by the cultural, political and moral climate, by the level of organised crime, by the patterns of illicit drug use, etc. etc.[58]

The broader, dynamic social and cultural environment of this country is just as influential in shaping Australia’s penal climate. To that extent, it may well be that answers to the question what is prison good for? will vary over time as the broader environment changes.

On the one hand, any move towards greater penal severity will bring with it added human and social costs, such as those borne by prisoners and their families. On the other, a culture of milder penal severity is likely, in time, to generate different social costs, such as those borne by victims of crime and their families. The risk is that as more people become victims of the kind of criminal offending that becomes more prevalent under a more lenient regime of punishment, so a mild penal climate gradually gives way to a harsher climate as social aversion to criminality hardens once again.

But this cycle between harsher and more lenient regimes of punishment is not inevitable, nor need the focus of punishment be solely on retribution. Criminal justice systems are attending increasingly to the efficacy of programs of restorative justice which attempt to help repair the harm done to victims of crime by encouraging offenders to take responsibility for their actions, appreciate the harm they have caused their victims and establish patterns of behaviour that will discourage further criminal activity.

TEXT BOX 2 – Indigenous incarceration

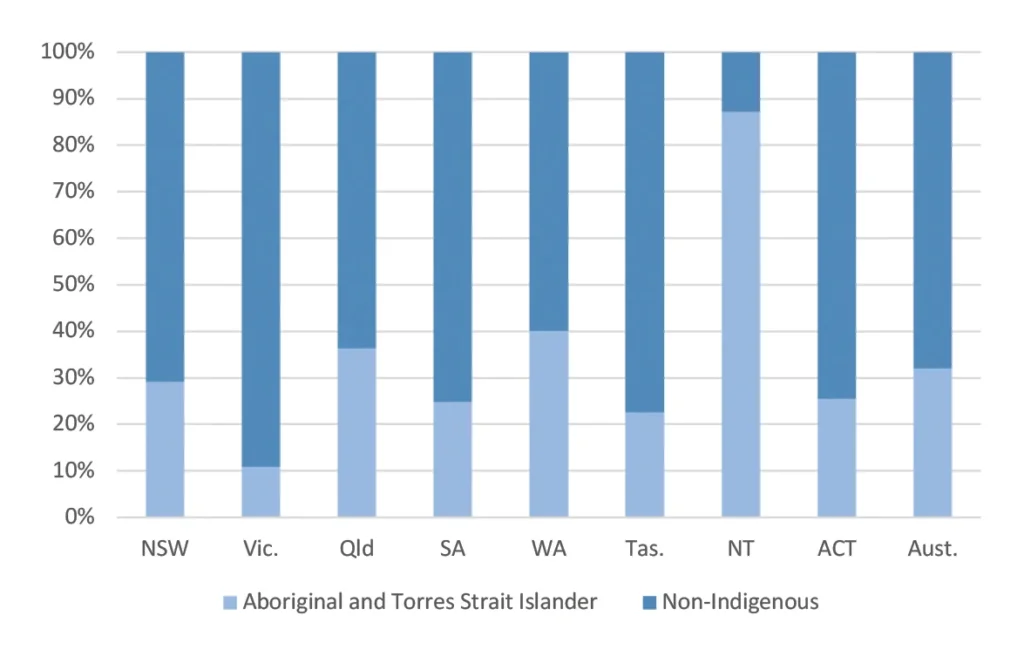

The 2021 national Census showed that 983,709 Australians identify as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander — that is, 3.9% of the total Australian population of 24,701,703. However, Indigenous people comprise 12,902 of the total Australian prison population, representing 31.8%. Chart 4 illustrates this over-representation.

In the Northern Territory, Indigenous people comprise 87% of the prison population (1,683 Indigenous prisoners compared to 247 non-Indigenous). In Queensland, Indigenous people comprise 5.5% of the state’s total population yet comprise 36% of the state’s prison population.

Chart 4: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners based on offence and charge by state and territory 2022

Source: Prisoners in Australia, 2022, States and Territories

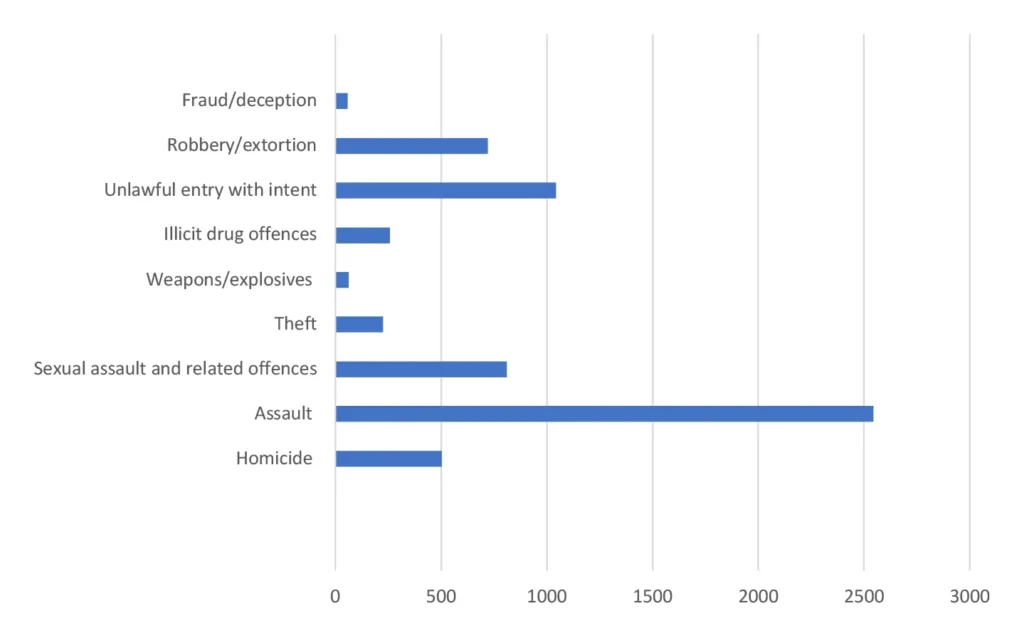

Furthermore, when breaking down the offences and charges of incarcerated Indigenous prisoners, 38 per cent of the population of Queensland was charged with acts intended to cause injury with 4,951 incarcerations. The second highest incarceration was unlawful entry with intent with 11 per cent at 1,431 and the third largest was sexual assault and related offences with 1,311 charges. Chart 5 indicates nine of the most common offences and charges faced by the Indigenous community.

Chart 5: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners based on offence and charge in 2022

Source: Prisoners in Australia, 2022, States and Territories

It is beyond the scope of this report to investigate with any thoroughness the efficacy of restorative justice programs in Australia. However, suffice it to note that the most common forms of restorative justice program operating here can involve a mediation process between victim and offender, as well as conferences to which members of the wider community can contribute in the search for reparation.

Restorative justice programs are widely used in the juvenile justice system in an attempt to avoid, where possible, sending young people to prison and thereby exposing them to the risk of repetitive cycles of offending and re-incarceration.

Evidence for the effectiveness of restorative justice programs is variable. Yet recent research indicates that in certain circumstances they may work as well as responses from the formal criminal justice system. Jacqueline Joudo Larsen has recorded high levels of satisfaction and perception that the process is fair. Re-offending rates have reduced while victim satisfaction has increased.[59]

However, such programs are likely to be more effective for minor crimes for which the offender is unlikely to go to prison in the first place. The community needs to be protected from dangerous criminals, something that restorative justice programs will not do.

An individual can find themselves incarcerated in prison for any one of a number of reasons. They may have been convicted of a crime; or are being held on remand; or serving a sentence imposed by statute rather than in virtue of the exercise of judicial discretion. Some, undoubtedly, have been imprisoned unjustly. Misfortune and trauma (whether social or mental) are therefore two principal conditions that characterise much, if not most, of the population of Australia’s prisons.

At the same time, as with any other service provided by the state, prison is expensive and costs are mounting. The Productivity Commission found that Australian prisons are operating at 116% of their design capacity with all the concomitant health and social problems that arise from overcrowding.[60] According to estimates by the Institute for Public Affairs, the current cost of Australian prisons is estimated at over $6bn each year; the cost of incarceration borne by the taxpayer is $405 per day per prisoner ($147,900 per prisoner per year).[61]

But Andrew Leigh emphasises that rising incarceration rates in Australia are not a coincidence, but the result of policy decisions. “While rates for most crimes have fallen, governments have deliberately chosen policies that have toughened bail laws and increased the amount of time that the typical prisoner serves.”[62] What accounts for these policy choices?

One factor is that decision made by governments about the amount of resources allocated to the criminal justice system — and corrective services, in particular — will be informed by assessment of the impact of criminality on the general public. Governments have made these decisions in response to public anxiety about crime. Even though crime rates for many crimes are falling, such as for homicide, robbery, face-to-face threatened assaults and physical assault, most Australians believe that rates for non-homicide crimes, such as drug-related crime and youth gang crime, have increased in recent years; about one third believe crime has increased a lot.[63] The consequent public demand for criminal justice is a significant driver in the investment governments make in law enforcement.

Increasing rates of incarceration also increase the loss of human and social capital that occurs as a result of these policy choices. Are these mounting costs to which these policies give rise — which are not just financial but also social — sustainable? Can Australia afford the costs of this “second convict age”? Australian governments are bound to have to address the challenges posed by these mounting costs and the burden this imposes on the taxpayer.

Although the Australian crime rate is falling, this report has sought to remind policy makers that despite a significant fall in the number of offenders, the prison population continues to grow.

Policy makers need to pursue suitable and viable alternatives to custodial sentences for certain categories of offence, and attend, in particular, to three key policy challenges:

- It is important to reduce the reach of mandatory sentencing provisions and restore the court’s discretion in the imposition of sentences.[64] Exercise of such judicial discretion is important because the court has the opportunity to weigh the personal circumstances of individuals appearing before them and to adjust sentences accordingly, if considered appropriate. Statutory imposition of mandatory sentences removes the capacity to exercise this discretion.

- Custodial sentences for those convicted of serious offences, especially those involving forms of bodily harm, will almost always be warranted. However, provision for non-custodial sentences (particularly when the offender in question is a young person) can help to avoid the detrimental impact of prison and help stem rising rates of recidivism.

- Governments must continue to address the seemingly intractable problem of over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders — including children, youth offenders and adults — in Australian prisons. Governments must remain committed to reducing those rates while, at the same time, striving to secure the safety of those living in Indigenous communities, especially women who are often victims of domestic violence. No easy solution presents itself.

Of course, society — both the general public and the media — may demand imposition of a custodial sentence as an expression of disgust at what has been perpetrated by an offender.[65] Non-custodial sentences, such as electronic monitoring, may fail to meet the punitive or retributive aims of the criminal justice system. However, it is equally clear that prison, in some circumstances, may do more harm than good to the offender — and thereby, wider society.

Conclusion

Prison must not be regarded as the only appropriate tool available in a criminal justice system used to bring about lower rates of crime. Indeed, resorting to imprisonment alone in an effort to reduce crime would signal that effective implementation of other preventative tools has weakened.[66] However, it remains the case that for some offences, the community’s sense of justice requires incarceration as punishment. Retribution remains an essential ingredient of every criminal justice system.[67]

This report has argued that when considering what prison is good for, it is not prison, alone, but the overall efficacy of the criminal justice system that helps determine crime rates. Even though is retains an important retributive function, prison — as a response to crimes committed — must be only one component of that system. As Weatherburn and Rahman have argued, corrective action to control crime is most effective when taken before crime spreads:

The most effective tools in the short run are those that block the opportunities for crime, increase the risk of apprehension and/or remove the rewards. If we reach the point where the only leverage we have over crime is an increase in the rate of imprisonment, the horse of crime control will have well and truly bolted.[68]

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for advice, guidance and critical comments they received from the Hon Andrew Bell CJ (NSW), Ms Una Doyle, Professor Arie Freiberg, Mr Michael Tidball, Mr Joseph Waugh and Professor Don Weatherburn.

Appendix 1

Prison in Australia: who is sent to prison?

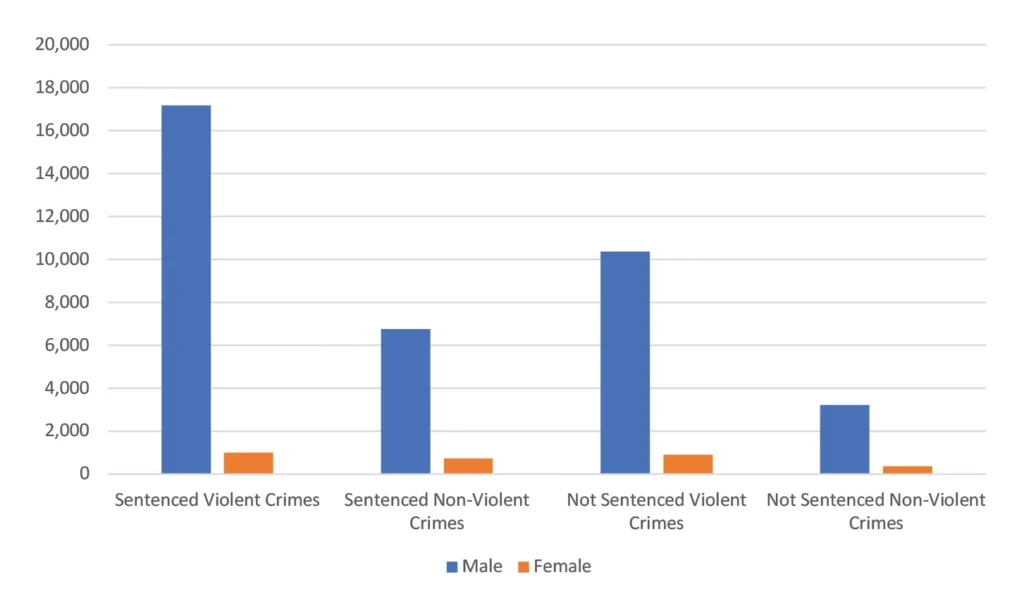

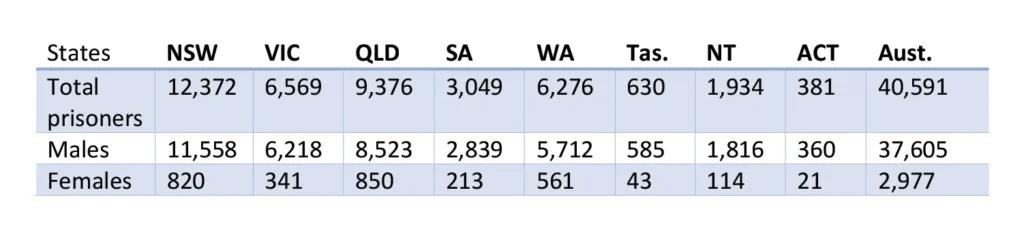

Any assessment of the efficacy of Australia’s prison system needs to consider the broad characteristics of the prison population. Table 1 gives an overview of the total prison population in Australia for 2022, indicating the distribution of imprisonment across gender and the states and territories.

Table 1: Total Australian prison population in 2022

Source: Prisoners in Australia, 2022, States and Territories

There is a significant gender disparity in the Australian prison population, with a notably higher number of male prisoners, accounting for 92% of the incarcerated population.

There is also a clear gender disparity between the types of offences for which prisoners are sentenced (see chart 6). Among female prisoners, a higher number are sentenced for violent crimes (994) as compared with non-violent crimes (726). In contrast, males display a more extensive presence in both categories, with remarkably higher number sentenced for violent crimes (17,166) and a significant number sentenced for non-violent crimes (6,743).

Chart 6: Prisoners by Gender, Crime Severity and Sentence Status during 2022

Source: Prisoners in Australia, 2022, Prisoner characteristics

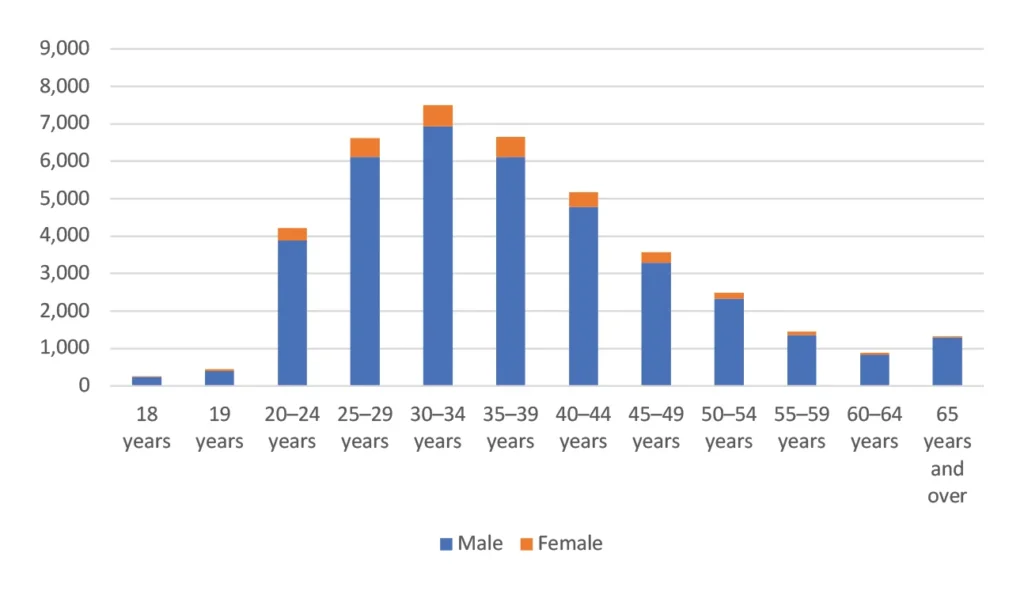

Chart 7 shows the age distribution of Australian prisoners as of 2022 and also indicates the significant gender disparity prevailing in Australian criminal justice systems.

Chart 7: Age of Australian prisoners in 2022

Source: Prisoners in Australia, 2022, Prisoner characteristics

The highest numbers of male and female prisoners are to be found in the 30-34 age group. As the age groups advance, there tends to be a steady decrease in the number of prisoners, particularly among older age groups, indicating that older individuals are less commonly incarcerated — with some possibly too old to re-offend.

However, a report published in 2021 by the Sentencing Advisory Council of Victoria (VSAC) studied sentencing outcomes from 2010 to 2019 for offenders in Victoria who were 60 years old and over when sentenced. The report found that the number of older offenders increased by 82% over that period while the number of offenders aged under 60 increased by only 4%. While less likely to be sentenced for theft or assault, older offenders were more likely to be sentenced for fraud, sexual and drug offences.[69]

Indeed, while older offenders were less likely to have prior convictions than young offenders, they were more likely to be sent to prison than young offenders, especially by the higher courts of Victoria:

The increase in the higher courts was mainly due to an increase in historical sex offence cases involving older offenders. Almost one in five sex offence cases involving older offenders were sentenced 40 years or more after the offence.[70]

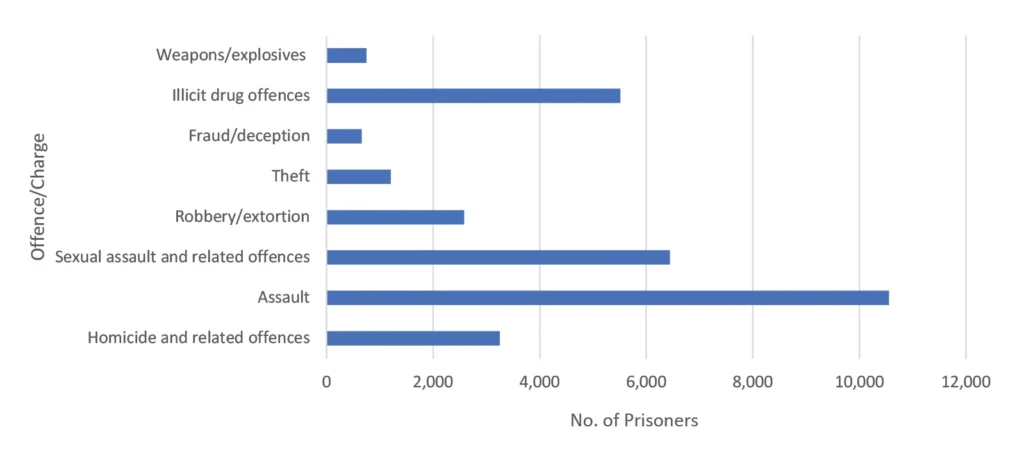

A broader survey of prisoners across Australia indicates those offences for which people are most likely to be sent to prison. Chart 8 shows seven key offences and charges, and the numbers sentenced for those offences and charges in 2022.

Chart 8: Offences and charges of sentenced prisoners in 2022

Source: Prisoners in Australia, 2022, Prisoner characteristics

Prisoners are among the most vulnerable members of society and often come from disadvantaged backgrounds. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare has reported that rates at which prisoners experience homelessness, unemployment, mental health disorders, chronic physical disease, communicable disease, tobacco and alcohol consumption, and illicit use of drugs tend to be higher than the general population.[71]

Measures were introduced in adult prisons after March 2020 to reduce the spread of Covid-19. These measures included vaccinations, social distancing and virtual visits. Covid-19 posed a serious risk to the physical health of prisoners because of the existing health vulnerability of the prison population. While prisoners are already affected by mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety disorders and psychotic disorders which can influence behaviour, levels of stress and decision-making, there is currently limited data on the specific impact of Covid-19. However, health care needs of prisoners are higher than the wider population and thereby only contribute to the disadvantage borne by Australian prisoners.[72]

Appendix 2

How much does prison cost?

During 2021-22, both the federal and state governments allocated more than $21 billion toward funding the criminal justice system, covering resources for law enforcement, courts, and corrective services. Among these expenditures, 26% was designated for corrective services.

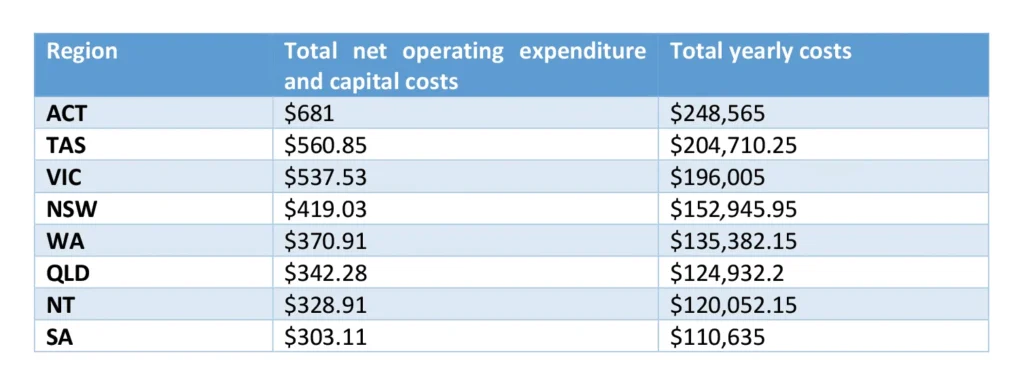

Over the past decade, corrective services have experienced a substantial surge in real recurrent expenditure with an increment of $2.5 billion in financial allocation. Between 2021 and 2022, the Australian prison system’s operations expenditure totalled $6.1 billion. Table 2 shows the cost of housing prisoners per day in each of the states and territories:

Table 2: Recurrent expenditure per prisoner and per offender per day between 2021 and 2022

The Australian average for prisoner costs is $405.18 per day and $147,890 yearly

Source: Productivity Commission, Report on Government Services 2023

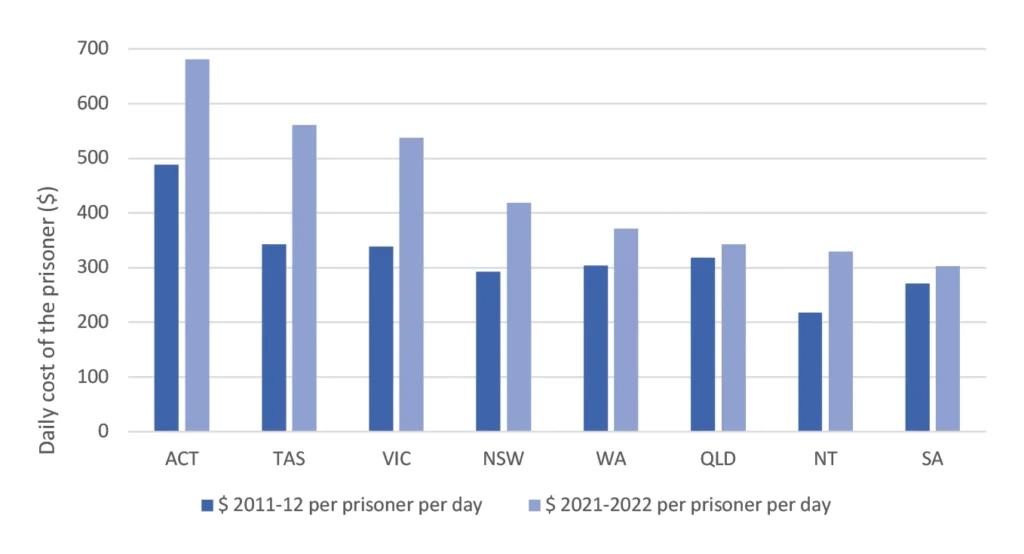

Table 3 shows a comparison for each state and territory between the real daily expenditure cost of an individual prisoner between 2011-2012 and 2021-2022.

Table 3: Daily expenditure per prisoner between 2011-2012 and 2021-2022

Source: Productivity Commission, Report on Government Services 2023

In 2011-2012, the Australian daily average cost of a prisoner was $304.79. However, there has been a 33% increase in this expenditure during the years 2021 and 2022.

It must be noted that during the Covid-19 pandemic, government restrictions across states and territories may have had an impact on prisoner costs; the ACT witnessed a substantial 40% rise in daily expenditure, while Tasmania and Victoria experienced increases of 64% and 59%.

Of particular concern is the significant proportion of the incarcerated population consisting of non-violent offenders, constituting approximately 38% of the overall prison population. The Queensland Productivity Commission found 30 per cent of individuals imprisoned for non-violent (or less serious) offences were chronic, but low harm, offenders who had usually committed several other offences prior to imprisonment.[73]

New prisons, such as the Chisholm Road Prison in Victoria, have been built, and existing Victorian facilities, like the Ravenhall Correctional Centre, have recently undergone costly expansions to meet the rising demand for prison space. The Barwon Southwest prison, an all-male maximum security prison in Victoria, is currently under construction with an estimated cost of $6.3 billion to operate over the next 25 years.

In NSW, Clarence Correctional Centre opened in 2020 as the largest and most expensive prison in Australia, costing $798 million to build. The prison population quickly grew from 90 prisoners to over 1,100 in its first year of operation, reaching 65 per cent of its maximum capacity. This rapid expansion necessitates additional funding and resources to maintain these facilities.

References

[1] “Australia murder/homicide rate 1990-2023”, Macrotrends https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/AUS/australia/murder-homicide-rate See also, “Crime and Justice”, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Crime and justice | Australian Bureau of Statistics (abs.gov.au)

[2] “Adults in prison”, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, (15 November 2023) https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/adults-in-prison#australias-prison-population

[3] In 1994 the population of Australia was 17.5 million and had grown to 26.2 million by 2021, an increase of 8.7 million people. See, “Population”, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Population | Australian Bureau of Statistics (abs.gov.au)

[4] “Twenty-seven years of prisoners in Australia”, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Twenty-seven years of Prisoners in Australia | Australian Bureau of Statistics (abs.gov.au).

[5] Andrew Leigh, The Second Convict Age: Explaining the Return of Mass Imprisonment in Australia, (IZA Institute of Labor Economics: March 2020).

[6] Productivity Commission 2021, Australia’s prison dilemma, Research paper, Canberra, 15.

[7] See, for example, Media release: “New ABS data reveals worrying rise in prisoner numbers”, Institute of Public Affairs (21 September 2023).

[8] Productivity Commission, as above, 3.

[9] Productivity Commission, as above, 9.

[10] Don Weatherburn & Sara Rahman, The Vanishing Criminal: Causes of Decline in Australia’s Crime Rate, (Melbourne, VIC: Melbourne University Press, 2021), 212.

[11] Maurice Bun, Richard Kelaher, Vasilis Sarafidis, Don Weatherburn, “Crime, deterrence and punishment revisited”, Empirical Economics, (2020), 59: 23030-2333, 2329.

[12] Vivien Stern, “Review: Charles Murray, Does Prison Work?, Journal of Forensic Psychiatry, (Vol. 9, No.3), 714-717, 717.

[13] Andrew Leigh, as above, 2.

[14] Andrew Leigh, as above, 15.

[15] Andrew Leigh, as above, 16.

[16] Queensland Productivity Commission – Summary Report, Imprisonment and Recidivism, (August 2019), 12.

[17] For a more detailed account of these theories and their strengths and weaknesses, see, further, C.L. Ten, “Crime and Punishment” in, Peter Singer (ed.), A Companion to Ethics, (Blackwell: Oxford, 1991), 366-372.

[18] Jean Hampton, “The Moral Education Theory of Punishment”, Philosophy & Public Affairs, Summer 1984 (Vol.13, No. 3), 208-238, 214.

[19] Jean Hampton, as above, 214.

[20] Arie Freiberg, “The Road Well Travelled in Australia”, Crime and Justice, Vol. 45 (2016), 419-457, 421.

[21] Arie Freiberg, as above, 424.

[22] See, for example, John Pratt, Penal Populism, (Routledge: London, 2006).

[23] Markarian v The Queen (2005) HCA 25, at 51 per McHugh J.

[24] See, Arie Freiberg, as above, 428.

[25] Victoria has a similar system of ‘standard sentences’.

[26] “Study shows increases in NSW sentence”, Media release, Judicial Commission of NSW (May 2010).

[27] Productivity Commission, as above, 42.

[28] Prisoners in Australia, 2022 | Australian Bureau of Statistics (abs.gov.au)

[29] Productivity Commission, as above, 39.

[30] The Productivity Commission reported that of people held on remand in 2020, 9.5% with offences which didn’t cause harm but exposed others to risk of low- to medium level harm to others, such as degree offences??? Doesn’t make sense

See, Productivity Commission, as above, 39.

[31] Productivity Commission, as above, 119.

[32] Productivity Commission, as above, 41.

[33] Joseph M. Bessette, “Let the punishment fit the crime”, Claremont Review of Books, (Winter 2022/23) Punish less and crime will increase; punish more and it will decrease. – Claremont Review of Books

[34] Lachlan Auld & Julia Quilter, “Changing the rules on bail: an analysis of recent legislative reforms in three Australian jurisdictions”, UNSW Law Journal, (Vol. 42, No. 2, 2020), 642-673.

[35] Section 22B Bail Act 2013 (NSW).

[36] Lachlan Auld & Julia Quilter, as above, 666.

[37] See, for example, Lachlan Auld & Julia Quilter, as above.

[38] Lachlan Auld & Julia Quilter, as above, 668.

[39] Don Weatherburn, “Is tougher sentencing and bail policy the cause of rising imprisonment rates? A NSW case study”, Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology, (2020, Vol. 53(4), 563-584, 565.

[40] Don Weatherburn, “A NSW case study”, as above, 565.

[41] Productivity Commission, Report on Government Services, (January 2023) C Justice – Report on Government Services 2023 – Productivity Commission (pc.gov.au)

[42] Productivity Commission, Report on Government Services, Justice Table, CA.4 (January 2023) https://www.pc.gov.au/ongoing/report-on-government-services/2023/justice

[43] World Population Review, Recidivism rates by country 2023 Recidivism Rates by Country 2023 (worldpopulationreview.com). See also, Carolyn Deady, “Incarceration and Recidivism: Lessons from Abroad”, (Pell Center for International Relations and Public Policy, March 2014) http://www.antoniocasella.eu/nume/Deady_march2014.pdf

[44] See, Mia Schlicht, The Cost of prisons in Australia: 2023, (Institute of Public Affairs, 2023).

[45] Productivity Commission, as above, 42.

[46] See, “Health of people in prison”, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, as above.

[47] New South Wales Auditor-General’s Report, Financial Audit, (Volume Seven 2015 Law and Order Emergency Services), 7 https://www.audit.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/pdf-downloads/2015_Nov_Report_Volume_Seven_2015_Part_One_Law_and_Order.pdf

[48] Report on Government Services, Australian Productivity Commission (31 January 2023) 7 Courts – Report on Government Services 2023 – Productivity Commission (pc.gov.au)

[49] New South Wales Auditor-General’s Report, Financial Audit, (Volume Seven 2015 Law and Order Emergency Services), as above.

[50] “Criminogenic” refers to a system of environmental or experiential factors that foster and produce criminal behaviours.

[51] Andrew Leigh, as above, 4.

[52] Don Weatherburn, private correspondence with the authors, (28 November 2023).

[53] See, “Specialist homelessness services annual report 2022–23”, (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, December 2023) https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/homelessness-services/specialist-homelessness-services-annual-report/contents/about

[54] Productivity Commission, as above, 44

[55] Productivity Commission, as above, 45

[56] See, further, Justice Reform Initiative, Justice Reform Initiative | Jailing Is Failing

[57] “Stories from the inside: failings of Australia’s criminal justice system”, Media Release 14 February 2022, (Deakin University) Stories from the inside: the failings of Australia’s criminal justice system | Deakin

[58] Jock Young, “Charles Murray and the American Experiment: The Dilemmas of a Libertarian” in, Charles Murray, Does Prison Work? (London: IEA Health and Welfare Unit, 1997), 33.

[59] See, further, Jacqueline Joudo Larsen, Restorative justice in the Australian criminal justice system, Research and public policy series No. 127, Australian Institute of Criminology (18 February 2014) Restorative justice in the Australian criminal justice system | Australian Institute of Criminology (aic.gov.au)

[60] Productivity Commission, as above, 8.

[61] See, Mia Schlicht, The Cost of prisons in Australia: 2023, (Institute of Public Affairs, 2023).

[62] Andrew Leigh, as above, 23.

[63] See, The Essential Report, Essential Research, (January 2018) https://www.essentialvision.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Essential-Report_160118.pdf

[64] See, Arie Freiberg, as above, 453.

[65] Philip Pettit describes this as part of the “outrage factor” which plays a significant role in systems of criminal justice. See, Philip Pettit, “Is Criminal Justice Politically Feasible?”, Buffalo Criminal Law Review, Vol. 5 No. 2 (January 2002) 427-450.

[66] Don Weatherburn & Sara Rahman, as above, 229.

[67] See Joseph M. Bessette, as above.

[68] Don Weatherburn & Sara Rahman, as above, 229.

[69] Sentencing Older Offenders in Victoria, Sentencing Advisory Council (Melbourne: Victoria, 2021).

[70] Sentencing Older Offenders in Victoria, as above.

[71] “Health of people in prison”, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023), Health of people in prison – Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (aihw.gov.au)

[72] “Health of people in prison”, as above.

[73] Queensland Productivity Commission, as above, 10.