In the second half of the twentieth century, Australia’s cheap, reliable electricity attracted heavy industry to our shores. By 1990, power-hungry copper, aluminium, lead, manganese and zinc smelters had popped up in each of the eastern states that would one day form the National Electricity Market (NEM). As Matthew Warren, former chief executive of the Australian Energy Council, the Energy Supply Association of Australia and the Clean Energy Council, describes the Australian grid:

In 2000, the coal and gas used were abundant and cheap, and the hydro was provided by rainfall. It was by international standards, about as cheap and reliable an electricity system as you could build. Its brutal simplicity, reliability and low cost had attracted global industries including aluminium and other processors. These were ‘the good old days’ of cheap and reliable electricity in Australia.[1]

But trouble has been brewing in Australia’s smelting paradise over the last two decades, as rising energy prices, carbon charges and foreign competition have taken their toll. These forces have eroded the comparative advantage Australia once enjoyed, shuttering existing industries and dissuading investors from building new ones. Government promises of a ‘renewable energy superpower’ Future Made in Australia built on intermittent renewables, batteries and hydrogen are looking increasingly implausible.

Rising Electricity Prices

Rising electricity prices have made headlines in recent years, cutting into household budgets and industry margins. Despite this, clear comparisons of Australia’s electricity prices with comparable countries over several decades remain scarce due to a paucity of reliable data.[2]

The International Energy Agency (IEA) does not publish industrial electricity prices beyond 2005 or residential electricity prices beyond 2021 for Australia.[3] This is because the IEA relies on national governments to provide reliable datasets and the Australian government does not publish an industrial electricity price dataset — likely due to the bespoke nature of industrial electricity contracts.[4] For residential price data, the Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) was publishing a Residential Price Trends Report, which the IEA referenced, up until 2021. However, the AEMC did not publish this report in 2022 or 2023, and in 2024 began publishing the report with an entirely different methodology, which prevented comparison with historical data. This was at the request of the federal and state governments, the energy regulator and the energy market operator.[5] It therefore appears that Australian governments and energy market bodies are directly responsible for a lack of reliable price data that could allow recent price rises in Australia to be compared with price trends across the globe.

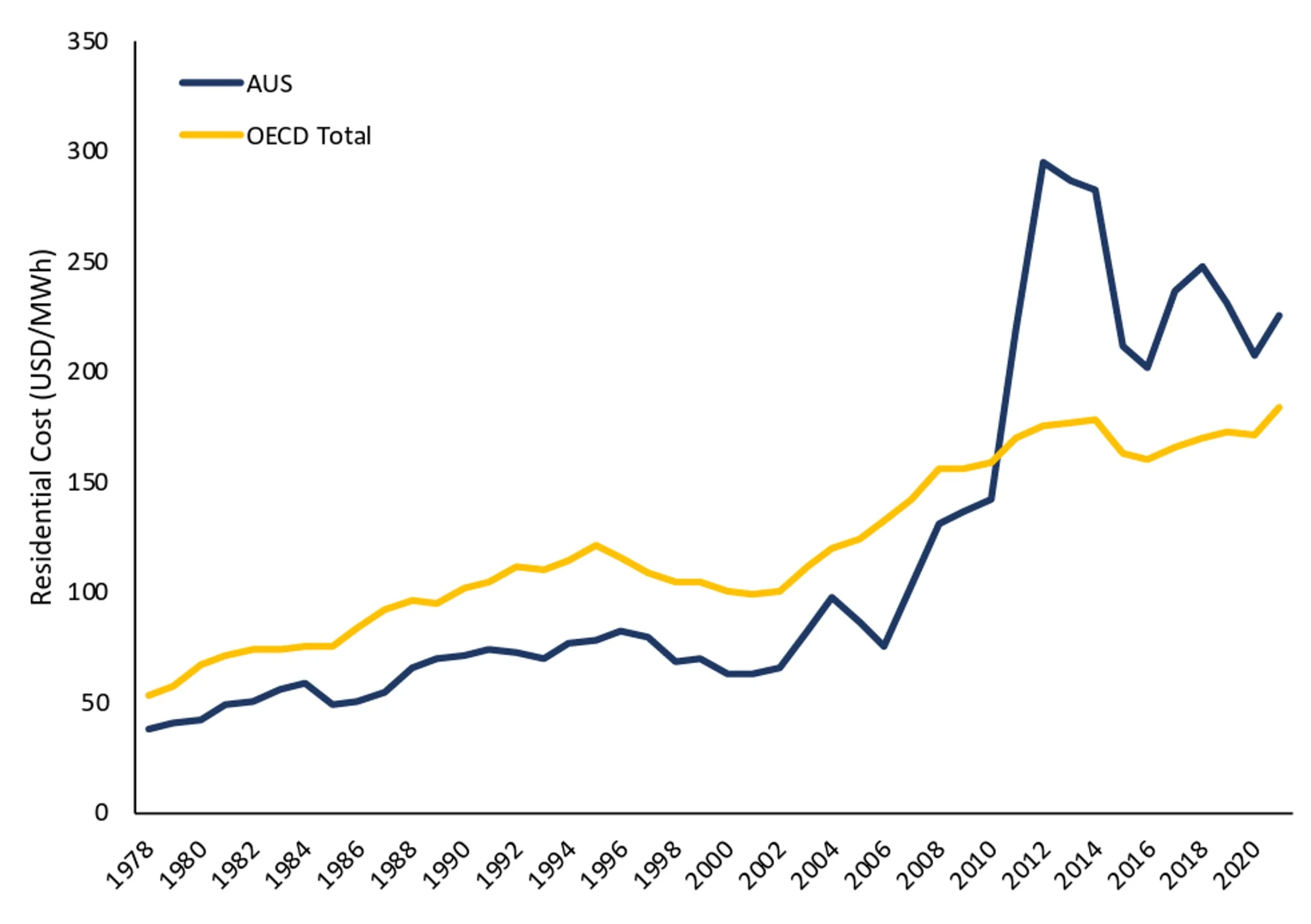

Data challenges aside, residential price data from the 1970s to 2021 provides a useful proxy for the changes in the global competitiveness of Australia’s industrial prices over time (Figure 1).[6] While other countries have experienced rising prices, Australia has suffered faster rises than the OECD average since the mid-2000s. Australia was once around 30% below the consumption-weighted average, but has shifted to being around 30% above the average since the early 2010s.

Figure 1. Australia’s residential electricity prices vs OECD consumption-weighted average

Source: Menzies Research Centre analysis of International Energy Agency data.

Since 2021, the trend shown in Figure 1 appears to have continued. Residential prices have continued to rise, with the Default Market Offer increasing in each distribution network area by between 3% to 29% annually apart from a small decrease of less than 3% for most networks in 2024-25.[7]

Anecdotal industry evidence suggests the trend is similar for industrial electricity prices, and that sustained increases in recent years have rendered Australia uncompetitive in the global market. BHP CEO Mike Henry recently remarked on Australia’s lack of global competitiveness on energy prices, saying, “The reality is right now Australia has electricity costs that are two to three times higher than countries that we are competing with and 50 to 100 per cent higher than the US”.[8] Managing Director of metals component manufacturer Abeck Group, Peter Angelico, commented on the rapid rise in energy bills, saying, “Just look at the last four years — I don’t know where they get the idea that costs are going to come down. I am concerned that this will keep going up, and that makes me uncompetitive with the importers.”[9]

However, the clearest sign that Australia’s electricity prices are now globally uncompetitive is the collapse of industries — such as smelting — that historically relied on cheap electricity to gain an advantage over international competitors.

Smelters Get Bailed Out or Go Bust

In recent years, smelter after smelter has announced its intention to close as heavy industry is rendered unviable by rising electricity costs. Major government bailouts and subsidies in various forms have become the status quo as policymakers attempt to stem the tide of industry leaving our shores.

In New South Wales, Tomago Aluminium, which has been operating since 1983, recently announced it is at risk of closure due to future energy prices rendering the smelter commercially unviable.[10] The federal government responded with an offer to provide subsidies in the billions of dollars through taxpayer-owned Snowy Hydro by offering below-market electricity contracts and increasing the supply of future renewables projects available to the smelter.[11] As of December 2025, Rio Tinto has accepted the offer and agreed to extend Tomago’s operations, though details of how much this will cost taxpayers — and the involvement of the NSW government — remain unclear.[12]

In Queensland, sustained electricity price spikes in 2017 led to Gladstone’s Boyne Smelters signalling its intent to cut jobs and production.[13] This eventually led to a commercial-in-confidence subsidy deal between Rio Tinto and the state government in 2024 to ensure the 1982-commissioned aluminium plant’s continued operation.[14] Under the agreement, the government will subsidise the smelter’s operations conditional on Rio Tinto signing power purchasing agreements with solar and wind farms, which likely would otherwise not be commercially viable.[15]

In South Australia, BHP has delayed making a final investment decision on extending its 1988-commissioned copper refining and smelting facility at the Olympic Dam mine, warning that energy prices and Australia’s overall financial settings would be critical in any future expansion going ahead.[16]

In Tasmania, the demise of Rio Tinto’s 1955-commissioned Bell Bay aluminium smelter has only been delayed by the state government agreeing to temporarily extend the existing power supply contract to provide more time for a federal government rescue package to be negotiated.[17] Bell Bay’s production is less than half that of Rio’s Tomago and Boyne smelters and is powered by hydroelectricity. Similarly, the Liberty Bell Bay manganese smelter — opened in 1962 — has yet to restart production after the plant was mothballed in May 2025, citing rising energy costs as a key factor putting pressure on the business.[18]

The strain of rising energy costs is being felt by more than just the smelting industries in Australia. Rising prices are also taking their toll on steelmaking. Whyalla steelworks has received a $2.4 billion government bailout, with rising and increasingly volatile energy costs in South Australia being a key reason for its failure.[19] BlueScope has warned that high gas prices are pushing domestic manufacturing to a tipping point, with CEO Mark Vassella saying energy costs in Australia are now three to four times higher than in the US, which risks undermining the country’s Future Made in Australia vision.[20] Western Australia has relatively low domestic gas prices due to implementing a 15% domestic reservation scheme for offshore LNG projects in 2006.[21] However, the east coast — which did not implement such a policy — has suffered from high gas prices in recent years. This is largely due to Santos signing large long-term supply contracts with Asian buyers in the early 2010s but later deciding some of the gas reserves were too difficult to tap. To fill the shortfall, Santos has siphoned gas from the domestic market, trebling the prices paid by domestic consumers over the last decade as gas supply has remained constrained.[22]

It is not only rising costs that have crippled industry. Reliability concerns are now coming to the fore. In Western Australia, production at the Kalgoorlie rare earth processing facility — opened in 2024 — slumped by about a third in the last quarter of 2025, undermining Lynas Rare Earths’ expansion plans, as more frequent and prolonged grid outages interrupted power supply. [23] These outages appear to have been caused by Kalgoorlie’s reliance on a single transmission line combined with Western Australia’s attempts to transition to renewable energy.[24]

Our Past Advantage

While Australia’s low-cost electricity advantage appears to have now vanished, clear evidence of its existence in past decades can be found in the decisions made by smelters to locate their operations on our shores. The Tomago aluminium smelter provides a case in point.

Low-cost electricity is crucial for aluminium smelting, as electricity accounts for around 40% of operating costs.[25] It is therefore unsurprising that the first factor cited in the 1980 Environmental Impact Statement in favour of building an aluminium smelter at Tomago was “a reliable source of electricity at relative low cost”, with other factors including “close proximity to raw material sources and potential markets and a stable economic and political climate conducive to investment”.[26] The Statement provides illuminating insight into how Australia became such an attractive location for the aluminium industry during this period:

Prior to 1973, aluminium producers located smelters near major markets in North America and Europe where they relied on hydro-electric power and oil-burning power stations for the supply of electricity. Economies arising from a developed infrastructure and tariff structures which favoured the import of the raw materials bauxite and alumina, rather than aluminium also contributed to the attractiveness of these countries. Subsequently, the decline in fuel availability, particularly oil, and the associated increase in the price of crude oil on international markets, significantly raised production costs in Europe and the USA, and the international aluminium industry saw the need to investigate alternative locations for investment in smelter capacity. Australia became a focus of attention because of its reliable supplies of primary energy, especially coal and natural gas, large bauxite reserves, fewer infrastructure problems than many other countries, a skilled labour force and political stability.[27]

As the quote above suggests, the 1973 oil crisis was a major factor in North America and Europe becoming less attractive for the smelting industry. The crisis was caused by cuts in oil production and an embargo imposed by Arab members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) on the USA, the Netherlands, Portugal, South Africa and other countries supporting Israel.[28] By comparison, energy-rich Australia became a much more attractive option in large part due to our cheap coal and plentiful reserves of bauxite. Our skilled labour force was another attractive feature, despite high labour costs arising from the 1974 wage shocks.[29] Australia’s low-cost energy advantage was sufficient to offset our high labour costs and secure our globally competitive position in the smelting industry, as we could use our cheap energy to value-add to our abundant natural resource base.

It has been argued that government electricity subsidies played a large role in providing smelters with power at globally competitive rates.[30] However, the evidence suggests government subsidies were by no means universal for smelters and that it was Australia’s abundant energy sources — particularly cheap coal — that ultimately provided our low-cost energy advantage. Although electricity assets were owned and run by vertically integrated, government-owned bodies prior to 1990,[31] none of the electricity contracts for aluminium smelting in New South Wales appear to have represented a net government subsidy. The Premier at the time stated that “the terms negotiated for supply of electricity to the three aluminium smelters ensure that the Electricity Commission will make a profit, after allowing for all capital costs and recurrent costs”.[32] Different state governments may have agreed to electricity contracts with other smelters charging below-market rates, but it is important to note the large, steady demand provided by smelters improved the business case for large coal plants, which ended up benefitting all consumers through cheaper electricity. Regardless of variations among individual arrangements between state-owned utilities and smelters, the fact that Australia had low-cost, reliable electricity meant that large government support packages were not required to lure the smelting industry to Australia.

In fact, many commercial and industrial consumers paid government-owned utilities substantially more than the cost of supplying their facilities prior to privatisation of the electricity sector. A 1991 Industry Commission report highlighted that there were substantial disparities between the cost of electricity supply and prices charged, with commercial and industrial consumers paying significantly more than the cost of supply.[33] Additionally, “excess capacity and gross overstaffing” during the 1980s meant electricity and gas were not supplied to consumers at least cost.[34] Over-investment in generation above what was needed to meet demand with reasonable reliability led to this excess capacity, otherwise known as ‘gold-plating’.[35] Overstaffing was a result of “union featherbedding”, in which unions imposed work practices which reduced the effort required from employees, increasing total labour costs for the same amount of output.[36] Yet despite these inefficiencies, the fact that “Australian energy prices compare favourably internationally” was taken for granted; the question at the time was merely how to improve a system that was already low cost.[37]

Australian industry clearly enjoyed a comparative advantage in energy costs which allowed electricity-intensive industries such as smelters to operate profitably on our shores. As rising costs and worsening reliability begin to bite, smelters have become the canary in the coal mine of an energy transition that is failing to deliver cheap energy to consumers. As profitability declines and investment in heavy industry abandons Australia, governments have had to resort to bailouts, often disguised as ‘investment’ in wind and solar projects that would never have been built without the government handing out direct subsidies or forcing industry to subsidise renewables in exchange for government support.

Conclusion

In past decades, cheap and abundant coal — combined with plentiful gas and some hydro — gave Australia a comparative advantage by providing heavy industry with access to low-cost, reliable electricity. Thus far, intermittent wind and solar have proven themselves unable to carry this mantle, with the resulting high electricity costs rendering heavy industries like smelting unviable. This has taken away Australia’s comparative advantage in smelting, despite our abundant natural resources and skilled workforce. As the Australian Aluminium Council has warned, “While Australia maintains its bauxite reserves, it has lost its historic energy advantage and there is increasing pressure on a limited skilled workforce.”[38] Some may argue we are simply in the ‘messy middle’ of the energy transition[39] and renewables will eventually restore our low-cost energy advantage and turn us into a renewable energy superpower.[40] However, this idea is not supported by international experience, the fundamental physics underpinning intermittent generation or the warning signs appearing in the Australian grid. On the contrary, all these key indicators point to the fact that the ‘renewable energy honeymoon’ has already drawn to a close in Australia and costs will continue to increase from here.[41] Only by expanding large-scale, dispatchable capacity with low fuel costs can we provide industry with the low-cost power it needs to support a Future Made in Australia. This future will remain out of reach if governments keep spruiking net zero policies that force the abandonment of cheap, abundant coal while retaining bans on nuclear power that prevent Australia from enjoying the benefits of cheap, abundant uranium.

[1] Warren, Matthew. 2019. ‘Black Out: How is energy-rich Australia running out of electricity?’. p 6.

[2] Mountain, Bruce. 2012. ‘Electricity Prices in Australia: An International Comparison’. Carbon + Energy Markets. https://www.aph.gov.au/DocumentStore.ashx?id=52040ade-8c93-4292-a50c-c8ce93c8236c; Mountain, Bruce. 2017. ‘Australian household electricity prices may be 25% higher than official reports’. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/australian-household-electricity-prices-may-be-25-higher-than-official-reports-84681.

[3] CIS correspondence with Data Sales Manager, International Energy Agency. 7/11/25.

[4] Acil Allen. 2021. ‘2021-22 regulated electricity price review: Updating retail costs. Final report’. p vii. https://www.qca.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/acilallenupdatingretailcosts2021-22regulatedelectricitypricesfinalreport-1.pdf.

[5] CIS correspondence with Anthony Rush, Economics Director, Australian Energy Market Commission. 22/1/25.

[6] Bongers, Geoff, Joshua Humphreys & Nathan Bongers. 2024. ‘Australian Retail Energy Prices in an International Context’. Menzies Research Centre. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5da3ff5001106247e50548dd/t/663daa9759b1f642fac13e6f/1715317406144/MRC_1040_Electricity+Prices+Report_web.pdf.

[7] Australian Energy Regulator. 2025. ‘Default market offer prices 2025-26: final determination’. p 9. https://www.aer.gov.au/industry/registers/resources/reviews/default-market-offer-prices-2025-26; Australian Energy Regulator. 2024. ‘Default market offer prices 2024–25: final determination’. p 8. https://www.aer.gov.au/industry/registers/resources/reviews/default-market-offer-prices-2024-25; Australian Energy Regulator. 2023. ‘Default market offer prices 2023–24: final determination’. p 6. https://www.aer.gov.au/industry/registers/resources/reviews/default-market-offer-2023-24/final-decision; Australian Energy Regulator. 2022. ‘Default market offer prices 2022–23: final determination’. p 7. https://www.aer.gov.au/industry/registers/resources/reviews/default-market-offer-prices-2022-23/final-decision.

[8] Williams, Perry. 2025. ‘BHP CEO Mike Henry issues warning on high Australian energy costs’. The Australian. https://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/bhp-ceo-mike-henry-issues-warning-on-high-australian-energy-costs/news-story/c9e0a08e8cf9cf36e93de60a6f92b1b0.

[9] Cranston, Matthew. 2025. ‘A survey of more than 500 Australian companies has found energy costs have become the top business challenge’. The Australian. https://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/a-survey-of-more-than-500-australian-companies-has-found-energy-costs-have-become-the-top-business-challenge/news-story/be7c2e1efbf7034fc78456dcab357b3b.

[10] Clifford, Ben. 2025. ‘Tomago Aluminium at risk of closure as energy prices continue to rise’. ABC. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-10-28/tomago-aluminum-closure-risk-energy-price-increase/105941120.

[11] Mizen, Ronald. 2025. ‘Labor puts billion-dollar Snowy Hydro play at heart of Tomago rescue’. Australian Financial Review. https://www.afr.com/politics/federal/labor-puts-billion-dollar-snowy-hydro-play-at-heart-of-tomago-rescue-20251123-p5nhnx.

[12] Coorey, Phillip. 2025. ‘PM unveils long-term power deal to keep Tomago smelter open’. Australian Financial Review. https://www.afr.com/politics/federal/pm-unveils-long-term-power-deal-to-keep-tomago-smelter-open-20251212-p5nn4w.

[13] ABC. 2017. ‘Boyne Smelter ‘to lose jobs’ after 500pc power price spike’. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-01-19/boyne-smelter-job-cuts-electricity-price-hike-stanwell-contract/8194880.

[14] Vorrath, Sophie. 2024. ‘Rio gets state support to shift Boyne smelters to renewables, says federal help needed too’. Renew Economy. https://reneweconomy.com.au/rio-gets-state-support-to-shift-boyne-smelters-to-renewables-says-federal-help-needed-too/.

[15] Rio Tinto. 2024. ‘Queensland Government and Rio Tinto partnership to support Gladstone’s Boyne Smelters’. https://www.riotinto.com/en/news/releases/2024/queensland-government-and-rio-tinto-partnership-to-support-gladstones-boyne-smelters; Queensland Government. 2024. ‘Securing the Future of jobs and industry in Central Queensland’. https://statements.qld.gov.au/statements/101093.

[16] Evans, Simon. 2025. ‘BHP still spending at Olympic Dam amid doubts over expansion plan’. Australian Financial Review. https://www.afr.com/companies/mining/bhp-still-spending-at-olympic-dam-amid-doubts-over-expansion-plan-20250923-p5mx6n.

[17] Evans, Simon & Peter Ker. 2025. ‘Tasmania grants Rio Tinto aluminium smelter 12-month reprieve’. Australian Financial Review. https://www.afr.com/companies/manufacturing/tasmania-grants-rio-tinto-aluminium-smelter-12-month-reprieve-20251104-p5n7pp.

[18] Evans, Simon & Peter Ker. 2025. ‘Tasmania grants Rio Tinto aluminium smelter 12-month reprieve’. Australian Financial Review. https://www.afr.com/companies/manufacturing/tasmania-grants-rio-tinto-aluminium-smelter-12-month-reprieve-20251104-p5n7pp.

[19] Australian Associated Press. 2025. ‘Troubled Whyalla steelworks gets $2.4bn government bailout as hunt for new owner begins’. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2025/feb/20/whyalla-steelworks-government-bailout-administration-sa; Senate Economics References Committee. 2017. ‘Australia’s steel industry: forging ahead’. p xii. https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Economics/Futureofsteel45th/~/media/Committees/economics_ctte/Futureofsteel45th/Report/report.pdf.

[20] Fuller, Kelly. 2025. ‘BlueScope warns soaring energy costs threaten Australian manufacturing as profit drops 90pc’. ABC. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-08-18/bluescope-warns-energy-costs-threaten-made-in-australia/105666186.

[21] Government of Western Australia. 2025. ‘WA Domestic Gas Policy: Development and application’. https://www.wa.gov.au/organisation/department-of-energy-and-economic-diversification/wa-domestic-gas-policy-development-and-application.

[22] Verrender, Ian. 2025. ‘Why Santos is behind your soaring electricity and mortgage costs’. ABC. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-10-14/why-santos-is-behind-your-soaring-electricity-and-mortgage-costs/105885202.

[23] Ker, Peter & Mark Wembridge. 2025. ‘Lynas blames WA’s ‘unpredictable’ clean power for production downgrade’. Australian Financial Review. https://www.afr.com/companies/mining/lynas-blames-wa-s-unreliable-clean-power-for-production-downgrade-20251125-p5ni5k; Thompson, Brad. 2025. ‘WA fails to deliver on promise of reliable and greener power supply to $800m Lynas processing plant’. The Australian. https://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/wa-fails-to-deliver-on-promise-of-reliable-and-greener-power-supply-to-800m-lynas-processing-plant/news-story/59d4857c23060419e9bb799428feac76.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Tomago Aluminium. 2005. ‘Submission by Tomago Aluminium Company Pty Ltd to the AER Review of the Electricity Transmission Revenue and Pricing Rules’. https://www.aemc.gov.au/sites/default/files/content/64a4b588-7e7c-4fa5-b99d-25baa0664618/Tomago-Aluminium-Company.pdf.

[26] Tomago Aluminium Company Pty Ltd. 1980. ‘Environmental impact statement for an aluminium smelter at Tomago, N.S.W.: Volume 1’. p 51. https://s3-ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/eis-pdf-records/EIS%20612%20Vol%201_AB019358.pdf.

[27] Tomago Aluminium Company Pty Ltd. 1980. ‘Environmental impact statement for an aluminium smelter at Tomago, N.S.W.: Volume 1’. p 51-52. https://s3-ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/eis-pdf-records/EIS%20612%20Vol%201_AB019358.pdf.

[28] Office of the Historian, Department of State, United States of America. 2016. ‘Oil Embargo, 1973–1974’. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1969-1976/oil-embargo.

[29] Cockerell, Lynne & Bill Russell. 1995. ‘Australian Wage and Price Inflation: 1971-1994’. Reserve Bank of Australia. https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/rdp/1995/pdf/rdp9509.pdf.

[30] Wood, Tony. 2012. ‘Who is killing aluminium smelting in Australia?’. Grattan Institute. https://grattan.edu.au/news/who-is-killing-aluminium-smelting-in-australia/.

[31] The Treasury. 1999. ‘Economic Roundup Spring 1999: Developments in Electricity’. Australian Government. p 52. https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-03/round4-4.pdf.

[32] Tomago Aluminium Company Pty Ltd. 1980. ‘Environmental impact statement for an aluminium smelter at Tomago, N.S.W.: Volume 1’. p 343. https://s3-ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/eis-pdf-records/EIS%20612%20Vol%201_AB019358.pdf.

[33] The Treasury. 1999. ‘Economic Roundup Spring 1999: Developments in Electricity’. Australian Government. p 52. https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-03/round4-4.pdf.

[34] Industry Commission. 1991. ‘Energy Generation and Distribution Volume I’. Commonwealth Government Printer. Canberra. p 1. https://assets.pc.gov.au/2025-05/11energyv1.pdf.

[35] The Treasury. 1999. ‘Economic Roundup Spring 1999: Developments in Electricity’. Australian Government. p 57. https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-03/round4-4.pdf.

[36] Quiggin, John. 2001. ‘Market-oriented reform in the Australian electricity industry’. The Economic and Labour Relations Review. 12(1). pp. 126–150. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/the-economic-and-labour-relations-review/article/abs/marketoriented-reform-in-the-australian-electricity-industry/A38E9BE455CD1A4F5C097FF3184DC745.

[37] Industry Commission. 1991. ‘Energy Generation and Distribution Volume I’. Commonwealth Government Printer. Canberra. p 2. https://assets.pc.gov.au/2025-05/11energyv1.pdf.

[38] Johnson, Marghanita. 2025. ‘Re: Draft 2025 Inputs Assumptions and Scenarios Consultation’. Australian Aluminium Council. https://aluminium.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/250211-Aluminium-2025-Inputs-Assumptions-and-Scenarios-Consultation.pdf.

[39] Mollard, Victoria. 2025. ‘Practical approaches – REZ and NEM decisions during the energy transition’. AEMC. https://www.aemc.gov.au/news-centre/speeches/practical-approaches-rez-and-nem-decisions-during-energy-transition.

[40] DCCEEW. 2025. ‘Albanese Government approves more renewable energy projects than any government in Australian history’. https://minister.dcceew.gov.au/plibersek/media-releases/albanese-government-approves-more-renewable-energy-projects-any-government-australian-history.

[41] Hilton, Zoe, Jae Lubberink, Michael Wu & Aidan Morrison. 2025. ‘The Renewable Energy Honeymoon: starting is easy, the rest is hard’. https://www.cis.org.au/publication/the-renewable-energy-honeymoon-starting-is-easy-the-rest-is-hard/.

Photo by Miguel Á. Padriñán