Housing affordability problem for young people

Housing affordability remains one of Australia’s clearest — and most frequently cited — examples of intergenerational inequality. Over the past 20 years, home ownership has fallen from 70% to 66%, and for young generations the uphill struggle to break into the housing market has only become steeper. Homeownership among 25-29 year olds has fallen from 43.2% to 36.1%.[1] For Gen Z the situation is looking even more dire with the hope of owning their own home turning into a pipe dream.[2]

What is housing affordability?

Housing affordability refers to the ability of people with an average income to pay for a home. It does not refer to simply the price of housing in an area; which can be driven up by high incomes but still be affordable relative to those incomes. But the term ‘housing affordability’ is often confused with ‘affordable housing’ which refers to government-subsidised housing for low-income earners.

The intergenerational struggle

When Boomers were in their prime home-buying years in the early 1980s, it took a little over 2 years to save for a 20% deposit on a median priced home. When Gen X entered the market in the 1990s it took just under 3 years. Now for a millennial household it takes over 5.5 years to save for a deposit. A household earning the median income in Australia can now afford just 13% of homes sold across the country — and that percentage is likely even smaller in our major cities.[3]

The ratio of median house prices to incomes has roughly doubled from 1989 to 2023. In 1989 it peaked at five times the amount but was less than four for most of the 1980s. By January 2023 it was 7.9 times, having peaked at 9 times during the pandemic housing boom.[4]

So, it’s no surprise young people are struggling to purchase their first homes and the largest decline in homeownership is among those aged 25–44.[5]

The wage-price race

Investors tend to assume housing prices always go up, with everyone from Mum and Dad investors to superannuation funds putting a significant proportion of their eggs in the property basket. But unaffordable housing is not an inevitable result of capitalism. Rather, in a functioning market the idea that housing prices will outpace wages should not be a certainty.

Why does the problem exist?

The failure to allow the private market to operate freely is the key driver of the current housing crisis in Australia. The regulatory framework has stopped Australia from building enough housing, and the housing we are building isn’t located where people want to live.

What about tax concessions?

Negative gearing and capital gain discounts for investors can feel like salt in the wound to young people unable to afford even a first home. However, these tax concessions can only be credited with increasing housing prices by 1-4%. Further they help reduce rents for those same young people struggling to save for that first home deposit. [6]

The tyranny of the minority

Local governments are heavily influenced by the view (or perceived views) of their constituency. Architects demand heritage protections which turn entire neighbourhoods into time capsules, and NIMBYs want to preserve the ‘character’ of the neighbourhood they originally bought into.

Councils believe, rightly or wrongly, that voters don’t want density, and are easily swayed by NIMBYs. Further, councillors represent nearby residents, not the direct beneficiaries of increased housing supply — the newcomers moving into the area. [7]

“Local governments will act like a cartel, restricting supply and driving up the price of housing. That benefits local residents but harms potential residents from outside the area and future generations.” ~ Peter Tulip

While it is clear many people are reluctant to see change in their own neighbourhoods, those very genuine feelings cannot be allowed to outweigh the need for more housing. [8]

What people want

What is less clear is the assumption that most people prefer to live in single family suburban homes with rotary clotheslines and space to BBQ in the backyard.

In fact, 59% of Sydneysiders and 52% of Melbournians reported in 2011 they would prefer to live in mid- to high-density housing. Yet, at the time of the survey only 38% of Sydney’s and 28% of Melbourne’s housing fell into those categories.[9] The mid- to high-density supply had improved by 2021 — to45.9% in Sydney and 34.4% in Melbourne —but still fails to meet the preferences of the population.[10]

Further, the values of younger generations often trend towards higher density; making it reasonable to expect the demand for mid- to high-density housing to increase over time. For example, Gen Z and Millennials tend to be environmentally-focused, so are more likely to prefer walkable neighbourhoods with easy access to public transport (as fewer own cars than previous generations).

However, zoning regulations tend to preference single-family zoning over other housing types. We need diversity of housing across locations so everyone can find housing that matches their needs.

The bureaucratic hurdles

The process is the punishment for many developers; delaying — and outright stopping — their ability to build, and risking the viability of projects. Rising interest rates and escalating construction costs can quickly transform an initially feasible project into an unviable one. Moreover, the prolonged delays can have a significant impact on a project’s eligibility for funding.

Councils and community complaints force projects to downsize or reduce the number of affordable units in a project plan.

Exclusionary zoning practices further compound the issue, with restrictions such as single-family-only zoning, height limitations, parking requirements, minimum lot sizes, and use restrictions. Particularly problematic is zoning that exclusively permits single-family homes — representing a severe constraint on diverse and inclusive housing development.

The ‘zoning tax’

Zoning tax is the price you pay for the legal right to put a dwelling on a piece of land. That legal permission to build on a site holds a large value as can be seen when an area is rezoned, and the price of the land immediately increases despite all other factors including location and size remaining the same.

Economists estimate average effects of the ‘zoning tax’ across a city by calculating the difference between the average sale price of a given dwelling and what it costs to build including what the developer can expect as a normal profit.

Zoning tax = Price – (construction costs and profit margins)

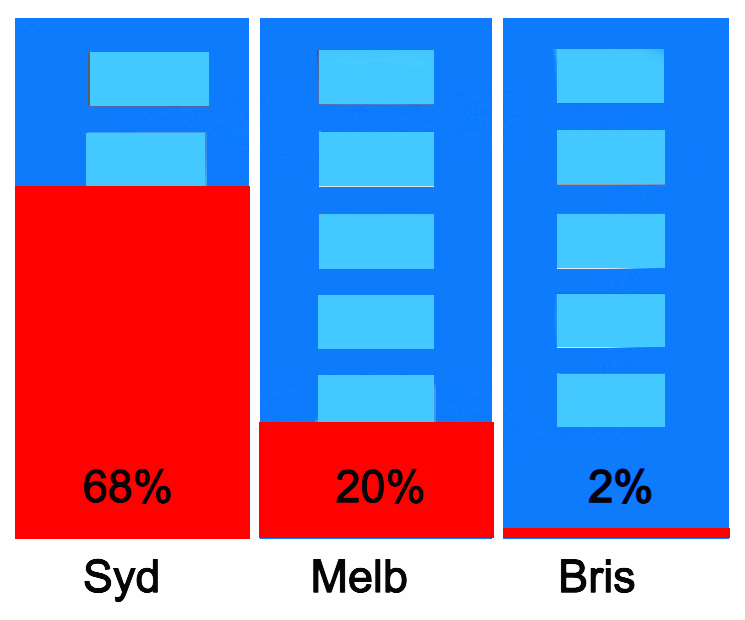

As shown in the figure below, the zoning tax accounts for $489,000 or 42% of the price of a home in Sydney, $324,000 or 41% of the price in Melbourne, $159,000 or 29% of the price in Brisbane, and $206,000 or 35% of the price in Perth.[11]

Zoning tax as % of house price

Zoning tax as % of apartment price

The question of demand

The housing affordability issue is often blamed on high demand. More people are choosing to live alone, short-term letting is increasingly popular, and Australia is a high immigration country. However, demand only becomes a problem when supply is restricted and not allowed to meet the increased need for housing.

Sydney needs about 30,800 extra dwellings a year to match expected population growth. Essentially that means a baseline growth in the dwelling stock in each local government area of at least 1% a year.[12] This level of growth is well within the range of possibility but is stymied by our current regulatory environment.

How can this be achieved?

State governments could help alleviate the housing crisis by issuing general overrides for certain types of exclusions (for example allowing granny flats), ensuring the areas around public transport is zoned for mid- to high-density and setting mandatory targets for councils. As a means of enforcement, if councils failed to approve the allocated number of projects in the timeframe, the state could appoint a planning administrator or automatically relax zoning restrictions. State governments could also reward councils that beat their targets with incentive payments as well as building more infrastructure. [13]

The only way Australia will make housing affordable for future generations will be by increasing the housing stock.

Endnotes

[1] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (April 2023) “Home ownership and housing tenure” https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/home-ownership-and-housing-tenure.

[2] Wood, Richard (April 2023) “Most young Aussies giving up on home ownership, survey finds”, 9News

[3] Ryan, P. and A. Moore (2023) “Housing Affordability Report 2023” PropTrack https://www.proptrack.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/PropTrack-Housing-Affordability-Index-2023.pdf.

[4] Khaden, Nassim, “Boomer, Generation X or Millennials: Who has it worse when it comes to buying a home and paying it off”, ABC News, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-02-06/baby-boomers-generation-x-millennials-housing-interest-rate-rise/101929468.

[5] Parliament of Australia (March 2022) “The Australian Dream” The Standing Committee on Tax and Revenue, 2. General Overview of Housing Affordability, https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/House/Former_Committees/Tax_and_Revenue/Housingaffordability/Report/section?id=committees%2freportrep%2f024864%2f78749.

[6] Tulip, Peter (August 2023) “The Rental Crisis” Submission to the Senate Community Affairs Committee, https://www.cis.org.au/publication/the-rental-crisis-submission-to-the-senate-community-affairs-committee/.

[7] Tulip, Peter and Zachary Lanigan (April 2021) “Does high-rise development damage neighbourhood character”, Centre for Independent Studies, https://www.cis.org.au/publication/does-high-rise-development-damage-neighbourhood-character/.

[8] Tulip, Peter (March 2023) “Where should we build new housing? Better Targets for local councils”, Centre for Independent Studies, https://www.cis.org.au/publication/where-should-we-build-new-housing-better-targets-for-local-councils/.

[9] Kelly, Jane-Frances (November 2011) “Getting the housing we want”, Grattan Institute https://grattan.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/117_report_getting_the_housing_we_want.pdf\

[10] Australia Community Profile, .id the population experts, https://profile.id.com.au/australia/dwellings?WebID=260

[11] Tulip, Peter (December 2020) “Planning restriction harm housing affordability”, Centre for Independent Studies, https://www.cis.org.au/publication/planning-restrictions-harm-housing-affordability/.

[12]Tulip, Peter (March 2023) “Where should we build new housing? Better Targets for local councils”, Centre for Independent Studies, https://www.cis.org.au/publication/where-should-we-build-new-housing-better-targets-for-local-councils/.

[13] Tulip, Peter (March 2023) “Where should we build new housing? Better Targets for local councils”, Centre for Independent Studies, https://www.cis.org.au/publication/where-should-we-build-new-housing-better-targets-for-local-councils/.